The civilization of Babylonia and Assyria

Its remains, language, history, religion, commerce, law, art, and literature

by Morris Jastrow | 1915 | 168,585 words

This work attempts to present a study of the unprecedented civilizations that flourished in the Tigris-Euphrates Valley many thousands of years ago. Spreading northward into present-day Turkey and Iran, the land known by the Greeks as Mesopotamia flourished until just before the Christian era....

Part IV

There is another feature of Babylonian architecture which needs to be touched upon before we leave the subject. At Warka, Telloh, Nippur and Babylon remains of arches were found at a depth which left no doubt as to the great antiquity to which the construction of arches is to be traced back in the Euphrates Valley at least to 3000 B.C. The span of these arches is not large and the construction is very irregular and crude, but nevertheless they illustrate the principle of the true arch ; and it has been plausibly conjectured that the discovery was suggested by the arched form of the primitive reed huts still in use by the natives in the villages.

These early arches were used as tunnels through which drains passed to carry off the rain water and the refuse from the structures beneath which they were erected. The extent to which the arch may have been used in Babylonian temples and palaces as a part of the construction proper is a question still in dispute, but since we find it employed in connection with the gateways of Assyrian palaces in the eighth century, it is a reasonable conclusion that the Assyrians merely imitated in this regard as in so many others the example furnished by the architects of the south.

This is all the more plausible because of the discovery at Bismya of a domed covering [1] for a structure that stood in close vicinity to the ancient temple at that place.

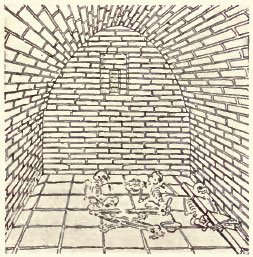

PLATE XL

Fig. 1, (left), Babylonian coffins of the older periods.

Fig. 2 (right), Assyrian grave vault.

We have at least one example of an arched gateway uncovered in the course of the excavations at Babylon by the German expedition while illustrations on Assyrian monuments show us temples with a series of domes not unlike those which constitute a feature of Mohammedan mosques and chapels at the present time. The courts of the temples, however, were uncovered and the public cult took place in the open air. Nor are there any good reasons for believing that either in the case of temples or palaces or private houses flat roofs were ever introduced. The absence of stone and of wood to serve as beams and rafters would prevent the architects from introducing such a covering.

The brick arch and the dome were therefore the two resources which must have been developed at a comparatively early period, and in the construction of which the ingenuity of the builders had an opportunity for wide play. The principle of the arch was further applied in the construction of vaults for the burial of the dead both in Babylonia and Assyria. In the mound Mukayyar covering the site of ancient Ur Taylor in 1854 discovered a number of such arched vaults, averaging 5 feet in height and 3/4 feet in breadth, and tapering from a length of 5 feet to about 7 feet.

About fifty years later, the German explorers working at Kaleh-Shergat, the site of the city of Ashur, came across vaults of precisely the same construction an interesting and valuable index of the continuity of architectural methods in both the south and the north. [2]

The depth at which these vaults were found at Kaleh-Shergat showed conclusively that the explorers were in the presence of tombs belonging to the older Assyrian period. The span of the arch in these Assyrian vaults was about five feet, the vaulted portion above the perpendicular walls on which the arch rested being a little over two feet high. The total height of the tomb was therefore about five and a half feet. The dead were placed in recesses along the walls or laid on the floor.

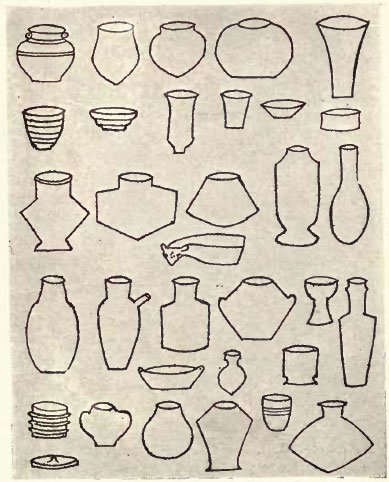

Digressing for a few moments to consider the methods of burial in Babylonia, we shall be led to the next subject to be considered the pottery. The oldest form of burial appears to have been to place the dead in small clay coffins not unlike a modern bath tub. Some of these were so small and so shallow as to suggest that the body was forced into these compartments by drawing up the knees and placing the body in a position that suggests the reproduction of the position of the child in the mother's womb.

Instead of coffins proper, large jars were used and the body sealed as it were between two siich jars, or again the bodies were placed on reed mats and covered with large earthen covers. In the later periods the tendency developed to increase the length of the coffins until in the neo-Babylonian and Persian periods we find long slipper-shaped receptacles with a narrow opening into which the body was forced.

In the early periods, the coffins and jars were almost wholly without ornament, but on those of (the later period, particularly on the slipper-shaped coffins, designs were worked out which, covered with a glaze, often gave a striking appearance to these coffins. By the side of vaults in which a number of bodies could be placed, we find square shaft tombs in each of which only one body was placed or a barrel-shaped tomb in which the dead was interred. [3]

The general custom appears to have been to bury the dead naked, but in some Assyrian burial vaults at Kaleh-Shergat, Andrae believes to have found traces of clothing. The connecting link between these various methods of burial and it would appear that the several customs were simultaneously employed and do not represent an evolutionary process is the desire to imprison the dead securely so as to prevent their troubling the living.

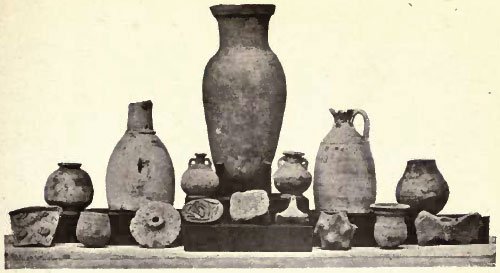

PLATE XLI

Fig. 1, Specimens of Babylonian pottery (Telloh)

Fig. 2, Shapes of pottery from Bismya

The disembodied spirit of the dead was a sort of menace to the living, and with a view of symbolizing the hope for security, the dead were forced into jars or coffins. Concomitant with this fear of the dead goes, however, the reverence and pity for those who have left the world of the living. Unable to provide for themselves, and yet supposed to have the same craving for food and drink and the same longing for activity as the living, the surviving relatives placed jars with food, ornaments, utensils and weapons in the tombs.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Banks, Bismya, p. 246.

[2]:

See Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orient Gesellschaft No. 8, facing p. 43; and for arches from Nippur and Uruk, Handcock, Mesopotamia^ Archceology p. 170.

[3]:

See also Jastrow, Bildermappe zur Babylonisch-Assyrischen Religion, Nos. 113-115, and above, PI. 14, Fig. 2.