The civilization of Babylonia and Assyria

Its remains, language, history, religion, commerce, law, art, and literature

by Morris Jastrow | 1915 | 168,585 words

This work attempts to present a study of the unprecedented civilizations that flourished in the Tigris-Euphrates Valley many thousands of years ago. Spreading northward into present-day Turkey and Iran, the land known by the Greeks as Mesopotamia flourished until just before the Christian era....

Part V

It is through the contents of the graves that we obtain an enlarged view of the various kinds of pottery in use in Babylonia and Assyria, though naturally our material is not limited to what was found in the graves.

A systematic study of this pottery such as has been made of Egyptian and Greek pottery has not yet been undertaken, and there is unfortunately much uncertainty as to the provenance of many of the specimens at our disposal, while in only a limited number of cases have we accurate data of the depth at which the material available was found. The potter's wheel appears to have been used at all periods, though many of the specimens show evidence of having been entirely hand-made.

The clay even in earlier times was burned to an almost black color, though in the case of the cheap pottery for every-day use this was probably not done, the clay being merely sun-dried as in the case of the cheaper kind of bricks. In the case of large urns and vases, straw was mixed with the clay in order to give it more substance, reminding us of the use of straw in the manufacture of bricks in Egypt. The best collection of pottery found up to the present time is that of Bismya, where every conceivable shape and size occurs from one inch to almost three feet. [1]

The shapes likewise vary from a very simple and almost crude design with merely a line or two at the top and bottom to elaborate decoration and very intricate shapes with graceful handles. At Nippur and Telloh several specimens of unusually large jars have been found, distinguished for their regular rope pattern, while showing a still higher form of art is a utensil perhaps an incense burner of most intricate shape and beautifully enamelled with a green color. This specimen was found at Telloh. [2]

The clay furnished so profusely by the alluvial soil, and which we have seen conditions the entire architecture of the Euphrates Valley, as it forms the writing material, lent itself to all kinds of artistic purposes. The earliest images of the gods as the earliest attempts at ornamentation and at sculpture were in clay. Some of these attempts were naturally exceedingly crude. These little images must have been manufactured in large quantities and sold to pious worshippers, to be kept in their homes as amulets to ward off the influence of evil spirits, or deposited as offerings in the temples. Clay moulds have been found into which the soft clay was pressed to bring about conventional shapes.

Considerable skill was shown in the modelling of the human face in these images, as may be concluded from the figure of a goddess with uplifted hands. There is an expression of adoration and servility in the face that is quite unmistakable and which is well supported by the position of the hands, suggesting a petition to some powerful being. Even more carefully executed is the picture of a goddess leading a worshipper into the presence of the deity. Strangely enough the portrayal of animals is less successful, though of course it may not be fair to judge from the few specimens at our disposal.

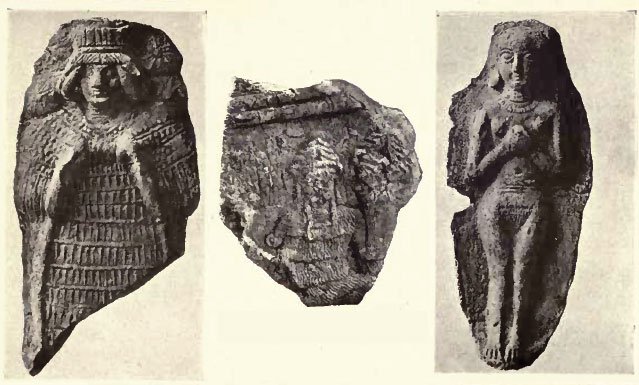

PLATE XLII

Fig. 1 (left), Votive statue of clay

Fig. 2 (middle), The God Ningirsu and his consort Bau

Fig. 3 (right), Votive statue of clay

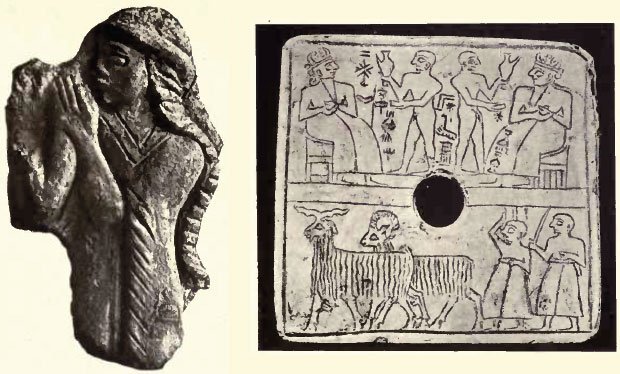

PLATE XLIII

Fig. 1 (left), Babylonian Goddess

Fig. 2 (right), Votive tablet of Ur-Enlil found at Nippur

Allowance, too, must be made for the individual style of artists, and yet we are probably safe in saying that except for the animals portrayed on glazed tiles, there was something stiff and grotesque in the Babylonian artist's reproduction of animals presenting a contrast in this respect to Assyrian art, where the portrayal of animals is superior to that of the human face, which rarely rises above a conventional level.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Banks, Bismya, pp. 175 and 261.

[2]:

De Sarzec et Heuzey, Decouvertes en ChdLdee, PI. 44 bis Pig. 6 a and 6 b ; for large jars, Babylonian Expedition of the University of Pennsylvania I, 2 PI. XXVI and Series D vol. 1, p. 406.