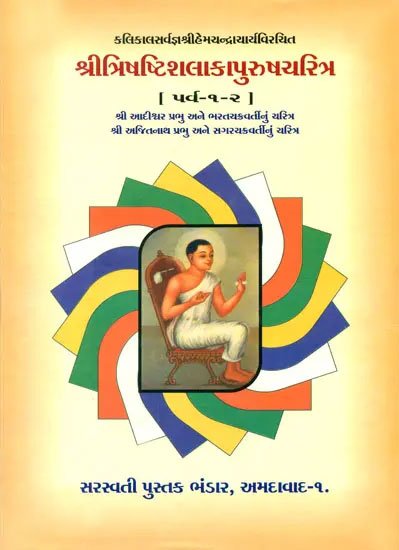

Trishashti Shalaka Purusha Caritra

by Helen M. Johnson | 1931 | 742,503 words

This page describes Bharata’s march through Tamisra which is the ninth part of chapter IV of the English translation of the Adisvara-caritra, contained within the “Trishashti Shalaka Purusha Caritra”: a massive Jain narrative relgious text composed by Hemacandra in the 12th century. Adisvara (or Rishabha) in jainism is the first Tirthankara (Jina) and one of the 63 illustrious beings or worthy persons.

Part 9: Bharata’s march through Tamisrā

One day the King summoned the general and instructed him, “Open the double-door of Tamisrā.” Taking on his head the King’s command like a wreath, the general went near Tamisrā and halted. Concentrating his mind on the god Kṛtamāla, the general made a four days’ fast. For all supernatural powers have their roots in penance. Then the general bathed and left the bath-house like a king-goose a pool, having wings in the form of white garments. Carrying in his hand a golden incense-burner like a toy golden lotus, Suṣeṇa sat at the door of Tamisrā. Then he looked at the doors and bowed. The great, even though possessing power, use conciliation first. Then he held a very splendid eight-day festival, an herb for the transfixing (with astonishment) of the Vidyādhara-women coming from Vaitāḍhya. The general designed out of whole rice the eight auspicious things which bring good fortune, like a conjuror a circle. The general took in his hand the Cakrin’s staff-jewel, destroying enemies, like Indra’s thunderbolt. Desiring to strike he withdrew seven or eight steps. Even an elephant desiring to strike withdraws a little. The general struck the double-door with the staff three times, making the cave give out a very loud noise, like a drum. The doors made of diamond, like eye-sockets of Mt. Vaitāḍhya, did open. Then the doors, opened by a blow with the staff, wept aloud, as it were, by their creaking.

The general reported to the King the opening of the doors, auspicious for a march of conquest of the northern divisions of Bharata. Mounting the elephant-jewel, the King with a complete and powerful army went to Tamisrā, like the moon. The King took the gem-jewel by means of which, like the tying of the tuft of hair on the head,[1] calamities arising from animals, men, and gods, do not befall; by which sorrow, as well as darkness, completely disappears; by which diseases, as well as blows from weapons, do not prevail; brilliant like the sun, attended by one thousand Yakṣas, four fingers (in dimension). (See notes on the maṇi-jewel) The destroyer of enemies set it on the right protuberance of the elephant like a golden cover on a full pitcher. Then the man-lion entered the cave-door like a lion following the cakra, accompanied by the four-part army in the cakra-formation.

The King took the cowrie-jewel which weighed eight suvarṇas,[2] was six-sided, twelve-edged, smoothsurfaced, provided with suitable bulk, weight, and height, always attended by one thousand Yakṣas, eight-cornered, destroyer of darkness for twelve yojanas, shaped like an anvil, with the brilliance of the sun and moon, four fingers (in each dimension).[3] He went in a zigzag course, drawing circles on the two sides of the cave at the end of each yojana. Forty-nine circles producing light were made, one to each yojana, with a diameter of five hundred bows. These remained, and the mouth of the cave was open so long as the illustrious Cakravartin lived on earth. By the light of the circles, the army advanced without stumbling, comfortably following the King who was following the cakra. In the light of the jewel the cave shone with the Cakravartin’s advancing army like the center of Ratnaprabhā with forces of Asuras, etc. By the army advancing in cakra-formation the cave was filled with a vast noise, like a churn by a churning-stick. The road in the cave, marked by straight lines at once by the chariots, with stones broken by the horses’ hooves, became like a city street, though unfrequented. Because of the army-people inside it, the cave became like the lokanāli[4] made horizontal.

In the middle of Tamisrā, the King came to the two rivers Unmagnā and Nimagnā resembling girdles for a garment. They had been made by the mountain like letters of command in the guise of rivers for men coming from the north and south of Bharatakṣetra. In the one even a stone rises like a gourd; in the other even a gourd sinks like a stone. Coming from the east wall of Tamisrā, going out through the west wall, they unite in the Sindhu. Then the carpenter made a path across them which was beyond criticism, like a long secret couch of the god of Mt. Vaitāḍhya. The path was produced in a moment by the Cakrabhṛt’s carpenter. For there was no delay of material from the Gehākāra-trees. Though made from many stones, their joints were fitted so closely that it looked as if made of one stone of such a size. With a surface as smooth as the hand, very hard like a diamond, it appeared to be made from the doors of the cave’s entrance. The Cakravartin with his army crossed the rivers, though, difficult to cross, with perfect ease, in the manner of the rule for compounding words of connected meaning.[5]

Gradually advancing with the army, the King arrived at the cave’s north entrance resembling the mouth of the north quarter. The doors opened at once of their own accord as if terrified after hearing the noise of the blow on the doors of the south entrance. Opening, they made the sound ‘sarat, sariti,’ as if hurrying the departure (saraṇa) of the Cakrin’s army. The doors were joined with the side-walls of the cave so closely that they appeared not to be there. Then the cakra, preceding the Cakravartin, came out of the cave first like the sun out of a cloud. The supreme lord of the powerful departed by the cave-entrance, like Bali by the chasm to Pātāla. The elephants left the cave like a wood on the plateau of Vindhya with a fearless, easy gait. The horses left the cave prancing gracefully, resembling the horses of the sun leaving the ocean. The chariots also left the cave of Vaitāḍhya, making the sky resound with their own noise, uninjured as if leaving a rich man’s house. The infantry, very powerful, issued from the mouth of the cave like serpents from the mouth of an ant-hill suddenly burst open.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

The tuft of hair, the coṭī, which Hindus wear on the head must always be tied, except in cases of mourning. Loose hair is considered inauspicious.

[2]:

A suvarṇa is about 175 grains troy (MW). Jamb. 54, p. 226a, gives a table starting with ‘madhuratṛṇaphala’ and ending with ‘suvarṇa.’ According to it, one suvarṇa=10,240 madhuratṛṇaphalas. In this same table, 80 guñjas=1 suvarṇa, which would be about 175 g. t.

[3]:

The kākiṇī was a cube. It is described also in Jamb. 54, p. 226. Pravac. 1213-17, p. 350. The descriptions agree with this one and add the facts that it was the shape of a goldsmith’s anvil, was made of gold, and could remove poison.

[4]:

The same as trasanāḍī. See App. I.

[5]:

‘Samarthaḥ padavidhih’ is the name of a grammatical sūtra to the effect that complete words must have a connected meaning in order to be made into a compound. See. Haim. VII. 4.122 and Siddhānta Kanmudī, XVII. 647. The comparison does not seem very felicitous. The rivers represent two words which have been joined.