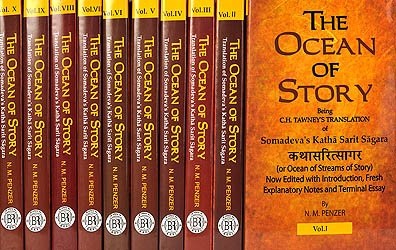

Kathasaritsagara (the Ocean of Story)

by Somadeva | 1924 | 1,023,469 words | ISBN-13: 9789350501351

This is the English translation of the Kathasaritsagara written by Somadeva around 1070. The principle story line revolves around prince Naravāhanadatta and his quest to become the emperor of the Vidhyādharas (‘celestial beings’). The work is one of the adoptations of the now lost Bṛhatkathā, a great Indian epic tale said to have been composed by ...

Chapter IV

[M] (main story line continued) HAVING related this episode to Kāṇabhūti in the Vindhya forest, Vararuci again resumed the main thread of his narrative:

1. Story of Vararuci...

While thus dwelling there with Vyāḍi and Indradatta, I gradually attained perfection in all sciences, and emerged from the condition of childhood. Once on a time when we went out to witness the festival of Indra we saw a maiden looking like some weapon of Kāma, not of the nature of an arrow. Then Indradatta, on my asking him who that lady might be, replied: “She is the daughter of Upavarṣa, and her name is Upakośā”; and she found out by means of her handmaids who I was, and drawing my soul after her with a glance made tender by love, she with difficulty managed to return to her own house. She had a face like a full moon,[1] and eyes like a blue lotus; she had arms graceful like the stalk of a lotus, and a lovely full[2] bosom; she had a neck marked with three lines like a shell,[3] and magnificent coral lips; in short, she was a second Lakṣmī, so to speak, the storehouse of the beauty of King Kāma. Then my heart was cleft by the stroke of love’s arrow, and I could not sleep that night through my desire to kiss her bimba[4] lip.

Having at last with difficulty gone off to sleep, I saw, at the close of night, a celestial woman in white garments; she said to me:

“Upakośā was thy wife in a former birth; as she appreciated merit, she desires no one but thee; therefore, my son, thou oughtest not to feel anxious about this matter. I am Sarasvatī[5] that dwell continually in thy frame, I cannot bear to behold thy grief.”

When she had said this she disappeared. Then I woke up and, somewhat encouraged, I went slowly and stood under a young mango-tree near the house of my beloved; then her confidante came and told me of the ardent attachment of Upakośā to me, the result of sudden passion; then I, with my pain doubled, said to her:

“How can I obtain Upakośā unless her natural protectors willingly bestow her upon me? For death is better than dishonour; so if by any means your friend’s heart became known to her parents, perhaps the end might be prosperous.

“Therefore bring this about, my good woman: save the life of me and of thy friend.”

When she heard this she went and told all to her friend’s mother, she immediately told it to her husband Upavarṣa, he to Varṣa his brother, and Varṣa approved of the match. Then, my marriage having been determined upon, Vyāḍi, by the order of my tutor, went and brought my mother from Kauśāmbī; so Upakośā was bestowed upon me by her father with all due ceremonies, and I lived happily in Pāṭaliputra with my mother and my wife.

Now in course of time Varṣa got a great number of pupils, and among them there was one rather stupid pupil of the name of Pāṇini; he, being wearied out with service, was sent away by the preceptor’s wife, and being disgusted at it, and longing for learning, he went to the Himālaya to perform austerities: then he obtained from the god who wears the moon as a crest, propitiated by his severe austerities, a new grammar, the source of all learning. Thereupon he came and challenged me to a disputation, and seven days passed away in the course of our disputation; on the eighth day he had been fairly conquered by me, but immediately afterwards a terrible menacing sound was uttered by Śiva in the firmament; owing to that our Aindra grammar was exploded in the world,[6] and all of us, being conquered by Pāṇini, became accounted fools. Accordingly full of despondency I deposited in the hand of the merchant Hiraṇyadatta my wealth for the maintenance of my house, and after informing Upakośā of it, I went fasting to Mount Himālaya to propitiate Śiva with austerities.

Upakośā, on her part anxious for my success, remained in her own house, bathing every day in the Ganges, strictly observing her vow. One day, when spring had come, she, being still beautiful, though thin and slightly pale, and charming to the eyes of men, like the streak of the new moon, was seen by the king’s domestic chaplain while going to bathe in the Ganges, and also by the head magistrate, and by the prince’s minister; and immediately they all of them became a target for the arrows of love. It happened too, somehow, that she took a long time bathing that day, and as she was returning in the evening the prince’s minister laid violent hands on her, but she with great presence of mind said to him:

“Dear sir, I desire this as much as you, but I am of respectable family, and my husband is away from home. How can I act thus? Someone might perhaps see us, and then misfortune would befall you as well as me. Therefore you must come without fail to my house in the first watch of the night of the spring festival when the citizens are all excited.”[7]

When she had said this, and pledged herself, he let her go, but, as chance would have it, she had not gone many steps farther before she was stopped by the king’s domestic priest. She made a similar assignation with him also for the second watch of the same night; and so he too was, though with difficulty, induced to let her go; but after she had gone a little farther, up comes a third person, the head magistrate, and detains the trembling lady. Then she made a similar assignation with him too for the third watch of the same night, and having by great good fortune got him to release her, she went home all trembling, and of her own accord told her handmaids the arrangements she had made, reflecting:

“Death is better for a woman of good family, when her husband is away, than to meet the eyes of people who lust after beauty.”

Full of these thoughts, and regretting me, the virtuous lady spent that night in fasting, lamenting her own beauty. Early the next morning she sent a maid-servant to the merchant Hiraṇyagupta to ask for some money in order that she might honour the Brāhmans; then that merchant also came and said to her in private:

“Show me love, and then I will give you what your husband deposited.”

When she heard that, she reflected that she had no witness to prove the deposit of her husband’s wealth, and perceived that the merchant was a villain, and so, tortured with sorrow and grief, she made a fourth and last assignation with him for the last watch of the same night; so he went away. In the meanwhile she had prepared by her handmaids in a large vat lamp-black mixed with oil and scented with musk and other perfumes, and she made ready four pieces of rag anointed with it, and she caused to be made a large trunk with a fastening outside. So on that day of the spring festival the prince’s minister came in the first watch of the night in gorgeous array.

When he had entered without being-observed, Upakośā said to him:

“I will not receive you until you have bathed, so go in and bathe.”

The simpleton agreed to that, and was taken by the handmaids into a secret dark inner apartment. There they took off his undergarments and his jewels, and gave him by way of an undergarment a single piece of rag, and they smeared the rascal from head to foot with a thick coating of that lamp-black and oil, pretending it was an unguent, without his detecting it. While they continued rubbing it into every limb the second watch of the night came and the priest arrived.

The handmaids thereupon said to the minister:

“Here is the king’s priest come, a great friend of Vararuci’s, so creep into this box,”

and they bundled him into the trunk just as he was, all naked, with the utmost precipitation; and then they fastened it outside with a bolt. The priest too was brought inside into the dark room on the pretence of a bath, and was in the same way stripped of his garments and ornaments, and made a fool of by the handmaids by being rubbed with lamp-black and oil, with nothing but the piece of rag on him, until in the third watch the chief magistrate arrived. The handmaids immediately terrified the priest with the news of his arrival, and pushed him into the trunk like his predecessor. After they had bolted him in, they brought in the magistrate on the pretext of giving him a bath, and so he, like his fellows, with a piece of rag for his only garment, was bamboozled by being continually anointed with lamp-black, until in the last watch of the night the merchant arrived. The handmaids made use of his arrival to alarm the magistrate, and bundled him also into the trunk and fastened it on the outside. So those three being shut up inside the box, as if they were bent on accustoming themselves to live in the hell of blind darkness, did not dare to speak on account of fear, though they touched one another.

Then Upakośā brought a lamp into the room, and making the merchant enter it, said to him:

“Give me that money which my husband deposited with you.”

When he heard that, the rascal said, observing that the room was empty:

“I told you that I would give you the money your husband deposited with me.”

Upakośā, calling the attention of the people in the trunk, said:

When she had said this she blew out the light, and the merchant, like the others, on the pretext of a bath, was anointed by the handmaids for a long time with lamp-black. Then they told him to go, for the darkness was over, and at the close of the night they took him by the neck and pushed him out of the door sorely against his will. Then he made the best of his way home, with only the piece of rag to cover his nakedness, and smeared with the black dye, with the dogs biting him at every step, thoroughly ashamed of himself, and at last reached his own house; and when he got there he did not dare to look his slaves in the face while they were washing off that black dye. The path of vice is indeed a painful one. In the early morning Upakośā, accompanied by her handmaids, went, without informing her parents, to the palace of King Nanda, and there she herself stated to the king that the merchant Hiraṇyagupta was endeavouring to deprive her of money deposited with him by her husband. The king, in order to inquire into the matter, immediately had the merchant summoned, who said: “I have nothing in my keeping belonging to this lady.” Upakośā then said: “I have witnesses, my lord; before he went, my husband put the household gods into a box, and this merchant with his own lips admitted the deposit in their presence. Let the box be brought here and ask the gods yourself.” Having heard this, the king in astonishment ordered the box to be brought.

Thereupon in a moment that trunk was carried in by many men. Then Upakośā said:

“Relate truly, O gods, what that merchant said, and then go to your own houses; if you do not, I will burn you or open the box in court.”

Hearing that, the men in the box, beside themselves with fear, said:

“It is true, the merchant admitted the deposit in our presence.”

Then the merchant, being utterly confounded, confessed all his guilt; but the king, being unable to restrain his curiosity, after asking permission of Upakośā, opened the chest there in court by breaking the fastening, and those three men were dragged out, looking like three lumps of solid darkness, and were with difficulty recognised by the king and his ministers. The whole assembly then burst out laughing, and the king in his curiosity asked Upakośā what was the meaning of all this; so the virtuous lady told the whole story.

All present in court expressed their approbation of Upakośā’s conduct, observing:

“The virtuous behaviour of women of good family who are protected by their own excellent disposition[8] only, is incredible.”

Then all those coveters of their neighbour’s wife were deprived of all their living, and banished from the country. Who prospers by immorality? Upakośā was dismissed by the king, who showed his great regard for her by a present of much wealth, and said to her: “Henceforth thou art my sister”; and so she returned home. Varṣa and Upavarṣa, when they heard it, congratulated that chaste lady, and there was a smile of admiration on the face of every single person in that city.

In the meanwhile, by performing a very severe penance on the snowy mountain, I propitiated the god, the husband of Pārvatī, the great giver of all good things; he revealed to me that same treatise of Pāṇini; and in accordance with his wish I completed it: then I returned home without feeling the fatigue of the journey, full of the nectar of the favour of that god who wears on his crest a digit of the moon; then I worshipped the feet of my mother and of my spiritual teachers, and heard from them the wonderful achievement of Upakośā; thereupon joy and astonishment swelled to the upmost height in my breast, together with natural affection and great respect for my wife.

Now Varṣa expressed a desire to hear from my lips the new grammar, and thereupon the god Kārttikeya himself revealed it to him. And it came to pass that Vyāḍi and Indradatta asked their preceptor Varṣa what fee they should give him. He replied:

“Give me ten millions of gold pieces.”

So they, consenting to the preceptor’s demand, said to me:

“Come with us, friend, to ask the King Nanda to give us the sum required for our teacher’s fee; we cannot obtain so much gold from any other quarter: for he possesses nine hundred and ninety millions, and so long ago he declared your wife Upakośā his sister in the faith, therefore you are his brother-in-law; we shall obtain something for the sake of your virtues.”

Having formed this resolution, we three fellow-students[9] went to the camp of King Nanda in Ayodhyā, and the very moment we arrived the king died; accordingly an outburst of lamentation arose in the kingdom, and we were reduced to despair. Immediately Indradatta, who was an adept in magic, said:

“I will enter the body of this dead king [see notes on the entering of another’s body]; let Vararuci prefer the petition to me, and I will give him the gold, and let Vyāḍi guard my body until I return.”

Saying this, Indradatta entered into the body of King Nanda, and when the king came to life again there was great rejoicing in the kingdom. While Vyāḍi remained in an empty temple to guard the body of Indradatta, I went to the king’s palace. I entered, and, after making the usual salutation, I asked the supposed Nanda for ten million gold pieces as my instructor’s fee. Then he ordered a man named Śakatāla,[10] the minister of the real Nanda, to give me ten million of gold pieces. That minister, when he saw that the dead king had come to life, and that the petitioner immediately got what he asked, guessed the real state of the case. What is there that the wise cannot understand?

That minister said: “It shall be given, your Highness,” and reflected with himself:

“Nanda’s son is but a child, and our realm is menaced by many enemies, so I will do my best for the present to keep his body on the throne even in its present state.”

Having resolved on this, he immediately took steps to have all dead bodies burned, employing spies to discover them, and among them was found the body of Indradatta, which was burned after Vyāḍi had been hustled out of the temple.

In the meanwhile the king was pressing for the payment of the money, but Śakatāla, who was still in doubt, said to him:

“All the servants have got their heads turned by the public rejoicing, let the Brāhman wait a moment until I can give it.”

Then Vyāḍi came and complained aloud in the presence of the supposed Nanda:

“Help, help; a Brāhman engaged in magic, whose life had not yet come to an end in a natural way, has been burnt by force on the pretext that his body was untenanted, and this in the very moment of your good fortune.”[11]

On hearing this the supposed Nanda was in an indescribable state of distraction from grief; but as soon as Indradatta was imprisoned in the body of Nanda, beyond the possibility of escape, by the burning of his body, the discreet Śakatāla went out and gave me that ten millions.

Then the supposed Nanda,[12] full of grief, said in secret to Vyāḍi:

“Though a Brāhman by birth, I have become a Śūdra. What is the use of my royal fortune to me though it be firmly established?”

When he heard that, Vyāḍi comforted him,[13] and gave him seasonable advice:

“You have been discovered by Śakatāla, so you must henceforth be on your guard against him, for he is a great minister, and in a short time he will, when it suits his purpose, destroy you, and will make Candragupta, the son of the previous Nanda, king. Therefore immediately appoint Vararuci your minister, in order that your rule may be firmly established by the help of his intellect, which is of god-like acuteness.”

When he had said this, Vyāḍi departed to give that fee to his preceptor, and immediately Yogananda sent for me and made me his minister. Then I said to the king:

“Though your estate as a Brāhman has been taken from you, I do not consider your throne secure as long as Śakatāla remains in office, therefore destroy him by some stratagem.”

When I had given him this advice, Yogananda threw Śakatāla into a dark dungeon,[14] and his hundred sons with him, proclaiming as his crime that he had burnt a Brāhman alive. One porringer of barley-meal and one of water was placed inside the dungeon every day for Śakatāla and his sons, and thereupon he said to them:

“My sons, even one man alone would with difficulty subsist on this barley-meal, much less can a number of people do so. Therefore let that one of us who is able to take vengeance on Yogananda consume every day the barley-meal and the water.”

His sons answered him:

“You alone are able to punish him, therefore do you consume them.”

For vengeance is dearer to the resolute than life itself. So Śakatāla alone subsisted on that meal and water every day. Alas! those whose souls are set on victory are cruel. Śakatāla, in the dark dungeon, beholding the death agonies of his starving sons, thought to himself:

“A man who desires his own welfare should not act in an arbitrary manner towards the powerful without fathoming their character and acquiring their confidence.”

Accordingly his hundred sons perished before his eyes, and he alone remained alive, surrounded by their skeletons. Then Yogananda took firm root in his kingdom. And Vyāḍi approached him after giving the present to his teacher, and after coming near to him said:

“May thy rule, my friend, last long! I take my leave of thee. I go to perform austerities somewhere.”

Hearing that, Yogananda, with his voice choked with tears, said to him:

“Stop thou and enjoy pleasure in my kingdom; do not go and desert me.”

Vyāḍi answered:

“King! life comes to an end in a moment. What wise man, I pray you, drowns himself in these hollow and fleeting enjoyments? Prosperity, a desert mirage, does not turn the head of the wise man.”

Saying this he went away that moment, resolved to mortify his flesh with austerities. Then that Yogananda went to his metropolis, Pāṭaliputra, for the purpose of enjoyment, accompanied by me, and surrounded with his whole army. So I, having attained prosperity, lived for a long time in that state, waited upon by Upakośā, and bearing the burden of the office of prime minister to that king, accompanied by my mother and my preceptors. There the Ganges, propitiated by my austerities, gave me every day much wealth, and Sarasvatī, present in bodily form, told me continually what measures to adopt.

[Additional note: The “entrapped suitors” motif]

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

This hardly seems complimentary from an English point of view, but the simile is a favourite one, not only in India, but in Turkey, Persia, Arabia and Afghanistan. Readers who have seen the full moon in the East will understand. —n.m.p.

[2]:

Literally, “ she was splendid with a full bosom... glorious with coral lips.” For uttama in the first half of śloka 6 I read upama. —As can be seen from the rock-carvings of ancient India, and also from the work of Court painters, the Hindus always admired the full breast. This was also considered a sine qua non among the Samoans. The Arabs insisted on firmness rather than size. The following description from the Nights (Burton, vol. i, p. 84) forms an interesting comparison to that in our text:—

“Her forehead was flower-white; her cheeks like the anemone ruddy bright; her eyes were those of the wild heifer or the gazelle, with eyebrows like the crescent-moon which ends Sha’abān and begins Ramazān; her mouth was the ring of Sulayman, her lips coral-red, and her teeth like a line of strung pearls or of camomile petals. Her throat recalled the antelope’s, and her breasts, like two pomegranates of even size, stood at bay as it were; her body rose and fell in waves below her dress like the rolls of a piece of brocade, and her navel would hold an ounce of benzoin ointment.”

All references to the Nights are to the original edition. —n.m.p.

[3]:

Considered to be indicative of exalted fortune .—Monier Williams.

[4]:

The bimba being an Indian fruit, this expression may be paralleled by “currant lip” in The Two Noble Kinsmen, i, 1, 216 , or “cherry lip” in Richard III, i, 1, 94.

[5]:

Goddess of eloquence and learning.

[6]:

See Dr Burnell’s Aindra Grammar for the bearing of this passage on the history of Sanskrit literature.

[7]:

And will not observe you.

[8]:

Instead of the walls of a seraglio.

[9]:

Dr Brockhaus translates: “alle drei rnit unsem Sckiilern”

[10]:

So also in the Pariśiṣṭaparvan (ed. Jacobi), but in the Prabandha - cintāmaṇi (Tawney, p. 193) it appears as Śakaḍāla, and in two MSS. as Śakaṭāli.—n.m.p.

[11]:

Compare the story in the Pañcatantra, Benfey’s translation, p. 124, of the king who lost his soul but eventually recovered it. Benfey in vol. i, p. 128, refers to some European parellels. Liebrecht in his Zur Volkskunde, p. 206, mentions a story found in Apollonius (Historia Mirabilium) which forms a striking parellel to this. According to Apollonius, the soul of Hermotimos of Klazomenæ left his body frequently, resided in different places, and uttered all kinds of predictions, returning to his body which remained in his house. At last some spiteful persons burned his body in the absence of his soul. There is a slight resemblance to this story in Sagas from the Far East, p. 222. By this it may be connected with a cycle of European tales about princes with ferine skin, etc. Apparently a treatise has been written on this story by Herr Varnhagen. It is mentioned in The Saturday Review of 22nd July 1882 as “Ein indisches Märchen auf seiner Wanderung durch die asiatischen und europäischen Litteraturen.”—See also Tawney’s Kathākoqa, Royal Asiatic Society, 1895, p. 38. For the burning of temporarily abandoned bodies see Benfey, op. cit., vol. i, p. 253, and vol. ii, p. 147.— N.M. p.

[12]:

Or Yogananda. So called as being Nanda by yoga or magic.—The name Indradatta is now dropped and hereafter he is referred to only as Y ogananda.—n.m.p.

[13]:

I read āśvāsya.

[14]:

Compare this story with that of Ugolino in Dante’s Inferno.