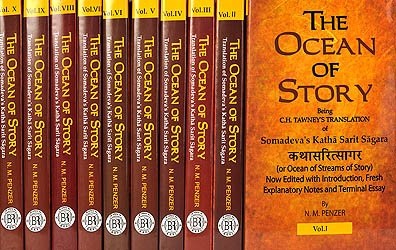

Kathasaritsagara (the Ocean of Story)

by Somadeva | 1924 | 1,023,469 words | ISBN-13: 9789350501351

This is the English translation of the Kathasaritsagara written by Somadeva around 1070. The principle story line revolves around prince Naravāhanadatta and his quest to become the emperor of the Vidhyādharas (‘celestial beings’). The work is one of the adoptations of the now lost Bṛhatkathā, a great Indian epic tale said to have been composed by ...

The “entrapped suitors” motif

Note: this text is extracted from Book I, chapter 4:

The “entrapped suitors” motif, as I would call it, is to be found throughout both Asia and Europe. I consider it forms, without doubt, an example of a migratory tale. The original form of the story, and origin of all the others, is that in the Ocean of Story. The incidents in it are of such a nature that the theory of numerous independent origins is unfeasible. A close inspection of the various stories I shall quote shows quite clearly the effects of local environment, and two distinct variants of story can be perceived:

1. The woman entraps three, or more, suitors and holds them up to ridicule before her husband, or the entire city.

2. The incident of a test article of chastity is added; accordingly the gallants try to cause the wife to be unfaithful, so that her action will have its effect on the magic article.

In both variants the gallants are hidden in trunks or sacks, and come out painted, naked, feathered, and so forth.

We will start our inquiry in India and move slowly westwards.

General Cunningham states on p. 53 of his The Stūpa of Bhārhut, London, 1S79j that in one of the sculptures he thinks he can clearly detect the dénouement of our story. If this is so, it proves that (1) the story is of Buddhist origin ; (2) it dates from the third century b.c. Barhut (or Bharahut) is about one hundred and twenty miles south-west of Allahābäd, and if the story, or at any rate some part of it, was well enough known to be represented in a bas-relief of an edifice raised over the ashes of some distinguished person, it seems quite possible that it would have found its way into the Bṛhat-Kathû, to be later utilised by Somadeva. Nevertheless the first literary appearance of the “entrapped suitors” story is undoubtedly in the Ocean of Story. In the story of Devasmitā in Chapter XIII of this volume we find a distinct resemblance to the tale of Upakośā, with the addition of the two red lotuses, of which the absent husband takes one and the wife keeps the other. Both remain unfaded while chastity lasts. Devasmitā has the gallants drugged, after which they are stripped, branded and thrown into a ditch of filth. Both these tales of Somadeva are strictly moral—the heroine is a virtuous married woman, she is faithful to her absent husband and shames the would-be adulterers. We shall see shortly how, on reaching other lands, incidents are altered and new ones of a distinctly coarse nature added.

In the Indian Antiquary, vol. ix, pp. 2, 3, 1873, G. A. Damant relates, in a story called “The Touchstone,” the tricks played by a woman on four admirers. The first arrival is smeared over with molasses, drenched with water, covered with cotton-wool and fastened in a window. The woman pretends to the other men that he is a Rākṣasa, which is sufficient for them to flee and leave her in peace. It is described in detail by Clouston in his Popular Tales and Fictions, vol. ii, pp. 303-305. In the chapter in which this occurs, headed “The Lady and her Suitors,” will be found many extracts or detailed descriptions of several of the stories mentioned in this note. In Miss Stokes’ Indian Fairy Tales (No. 28) the heroine is accosted by four men when selling her thread in the market. She gets them all in separate chests, which she sells to the men’s sons. The shame of the fathers when their sons open the chests can be imagined! (See also the note at the end of Miss Stokes’ book.)

There is a slight connection in one of the exploits of the Indian jester, Temal Ramakistnan (quoted by Clouston, op. cit., vol. ii, pp. 305-307). He makes the rājā and priest, from whom he wishes to obtain an oath of protection, imagine they are going to an assignation with the fair wife of a traveller; he then locks them up till he gets what he wants.

Proceeding westward from India we find a similar story to that under discussion in Thorburn’s Bannū, or Our Afghan Frontier (see Mélusine, p. 178).

In Persia the story soon became popular. It occurs in the Tūtī-Nāma of Nakhshabī; in the Thousand and One Days, by the Dervish Makhlis of Ispahān, where the wife is still virtuous and successfully shames her would-be lovers. It also appears in the Bahār-i-Dānish, or Spring of Knowledge, by’Ināyatu-’llāh. In this story the husband is in the hands of the police. His wife, Gohera by name, entraps the Kutwal (police magistrate) in a big jar and a kāzī in a chest, and finally gets her husband released. There is another Persian story worth mentioning— Gul-i-Bakāwalī, or The Rose of Bakāwalī, written by Shaykh ‘Izzat Ullāh in 1712. Four brothers get enticed into the house of a courtesan, lose everything by gambling, become her slaves and, after being branded on their backs as a mark of their shame, are released by the hero, their youngest brother. (For further details see Clouston’s A Group of Eastern Romances and Stories, 1889, p. 240 et seq.)

We now pass on to Arabia, where we find the story fully developed, with a few coarse additions inserted by the rāwī. It appears twice in the Nights (Burton, vol. vi, p. 172 et seq., and Supp., vol. v, p. 253 et seq.). The first of these is the tale of “The Lady and her Five Suitors.” As in the Persian Bahār-i-Dānish, so here the woman’s action is caused by the desire to free her husband from prison. She dresses the men in comical clothes and hides each of them in a kind of tall-boy which she has had specially made for the purpose. The five men are kept locked up in it for three days, and it is here that the rāwī takes care not to lose the chance of getting a laugh out of his audience by adding a few unpleasant details. The second story is “The Goodwife of Cairo and her Four Gallants.” The woman makes them strip and put on a gaberdine and bonnet. When the husband returns they are let out of the chest on the condition that they will first dance and each tell a story, which they do.

In The Seven Vazīrs an almost exact story to the first one mentioned in the Nights appears as the first tale of the sixth vazīr. It is entitled “Story of the Merchant’s Wife and her Suitors.” (See p. 181 et seq. of Clouston’s Book of Sindibād.)

In the Turkish History of the Forty Vezīrs, the twenty-first vezīr’s story bears a slight resemblance to the above, but there is only one man and he is the willing lover of the woman. (See Gibb’s translation, p. 227 et seq.) In Europe we find the story very widely spread. One of the most complete and oldest versions is fabliau entitled “De la dame qui attrapa un prêtre, un prévôt, et un forestier,” or “Constant du Hamel.” See Barbazan-Méon’s Fabliaux et Contes des Poètes Frangois des XIe-XVe siècles, 4 vols., Paris, 1808, iii, p. 296, and Montaiglon’s Recueil général et complet des Fabliaux des XIIIe et XIVe siècles, 6 vols., Paris, 1877, iv, p. 166 . In this version the gallants strip, bathe, get into a tub of feathers and are finally chased by dogs through the streets.

In Italy it forms, with variations, the eighth novel of the eighth day of The Decameron; the forty-third of the third deca of Bandello; the eighth novel of the ninth day of Sansovino; the fifth tale of the second night of Straparola; the eighth novel of Forteguerri, and the ninth diversion of the third day of the Pentamerone. There is also a faint echo in Gonzenbach’s Sicilianische Märchen, No. 55, pp. 359-362. Compare also No. 72 (6) in the Novellæ Morlini (Liebrecht’s Dunlop, p. 497). Fuller details of the Italian variants can be found in A. C. Lee’s The Decameron, its Sources and Analogues, 1909, pp. 261 - 266 . No. 69 of the Continental Gesta Romanorum begins with the story of a shirt of chastity. Three soldiers attempt to make it dirty, thereby showing the man’s wife has been untrue—with the usual result. In the English Gesta (Herrtage 25) three knights are killed. The best English version, however, is found in the metrical tale of “The Wright’s Chaste Wife,” Adam of Cobsam, circa 1462. (See Furnivall, English Text Society, 1865.) In this story a garland is the article of chastity, the gallants fall through a trap-door and are made to spin flax until the husband returns. Massinger’s play of 1630, The Picture, may be taken from the above. (See Clouston, Popular Tales, vol. ii, p. 292.)

In the story of the “Mastermaid” in Dasent, Tales from the Norse (2nd edition, p. 81 et seq.), a woman with magical knowledge consents to receive three constables on consecutive nights. On each man she employs her magic, making them do some foolish thing from which they are unable to get free till the dawn.

An Icelandic variant is found in Powell and Magnusson’s (2nd series) collection, entitled “Story of Geirlaug and Groedari.”

Finally in Portugal there is a variant in the sixty-seventh story in Coelho’s Contos Populares Portuguezes, 1879.—n.m.p.