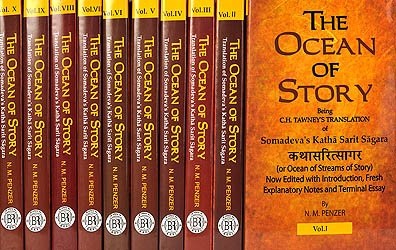

Kathasaritsagara (the Ocean of Story)

by Somadeva | 1924 | 1,023,469 words | ISBN-13: 9789350501351

This is the English translation of the Kathasaritsagara written by Somadeva around 1070. The principle story line revolves around prince Naravāhanadatta and his quest to become the emperor of the Vidhyādharas (‘celestial beings’). The work is one of the adoptations of the now lost Bṛhatkathā, a great Indian epic tale said to have been composed by ...

Chapter LIX

[M] (Main story line continued) EARLY the next day Naravāhanadatta, after he had performed his necessary duties, went to his garden by way of amusement. And while he was there he saw first a blaze of splendour descend from heaven, and after it a company of many Vidyādhara females. And in the middle of those glittering ones he saw a maiden charming to the eye, like a digit of the moon in the middle of the stars, with face like an opening lotus, with rolling eyes like circling bees, with the swimming gait of a swan, diffusing the perfume of a blue lotus, with dimples charming like waves, with waist adorned with a string of pearls, like the presiding goddess of the lovely lake in Kāma’s garden, appearing in bodily form.

And the prince, when he saw that charming, enamoured creature, a medicine potent to revive the God of Love, was disturbed like the sea, when it beholds the orb of the moon. And he approached her, saying to his ministers:

“Ah! extraordinary is the variety in producing fair ones that is characteristic of Providence!”

And when she looked at him with a sidelong look, tender with passion, he asked her:

“Who are you, auspicious one, and why have you come here?”

When the maiden heard that, she said:

“Listen, I will tell you.

“There is a town of gold on the Himālayas, named Kāñcanaśṛṅga. In it there lives a king of the Vidyādharas, named Sphaṭikayaśas, who is just, and kind to the wretched, the unprotected, and those who seek his aid. Know that I am his daughter, born to him by the Queen Hemaprabhā, in consequence of a boon granted by Gaurī. And I, being the youngest child, and having five brothers, and being dear to my father as his life, kept by his advice propitiating Gaurī with vows and hymns. She, being pleased, bestowed on me all the magic sciences, and deigned to address me thus: ‘ Thy might in science shall be tenfold that of thy father, and thy husband shall be Naravāhanadatta, the son of the King of Vatsa, the future Emperor of the Vidyādharas.’

“After the consort of Śiva had said this, she disappeared, and by her favour I obtained the sciences and gradually grew up. And last night the goddess appeared to me and commanded me: ‘To-morrow, my daughter, thou must go and visit thy husband, and thou must return here the same day, for in a month thy father, who has long entertained this intention, will give thee in marriage.’ The goddess, after giving me this command, disappeared, and the night came to an end; so here I am come, your Highness, to pay you a visit. So now I will depart.”

Having said this, Śaktiyaśas flew up into the heaven with her attendants, and returned to her father’s city.

But Naravāhanadatta, being eager to marry her, went in disappointed, considering the month as long as a Yuga.[1] And Gomukha, seeing that he was despondent, said to him:

“Listen, prince, I will tell you a delightful story.

83. Story of King Sumanas, the Niṣāda Maiden, and the Learned Parrot [2]

In old time there was a city named Kāñcanapurī, and in it there lived a great king named Sumanas. He was of extraordinary splendour, and, crossing difficult and inaccessible regions, he conquered the fortresses and fastnesses of his foes. Once, as he was sitting in the hall of assembly, the warder said to him:

“King, the daughter of the King of the Niṣādas, named Muktālatā, is standing outside the door with a parrot in a cage, accompanied by her brother Vīraprabha, and wishes to see your Majesty.”

The king said: “Let her enter.”

And introduced by the warder, the Bhilla maiden entered the enclosure of the king’s hall of assembly. And all there, when they saw her beauty, thought:

“This is not a mortal maiden; surely this is some heavenly nymph.”

And she bowed before the king, and spoke as follows:

“King, here is a parrot that knows the tour Vedas, called Śāstragañja, a poet skilled in all the sciences and in the graceful arts, and I have brought him he re to-day by the order of King Maya, so receive him.”

With these words she handed over the parrot, and it was brought by the warder near the king, as he had a curiosity to sec it, and it recited the following śloka:

“King, this is natural, that the black-faced smoke of thy valour should be continually increased by the windy sighs of the widows of thy enemies; but this is strange, that the strong flame of thy valour blazes in the ten cardinal points all the more fiercely on account of the overflowing of the copious tears wrung from them by the humiliation of defeat.”

When the parrot had recited this śloka, it began to re flect, and said again:

“What do you wish to know? Tell me from what Śāstra I shall recite.”

Then the king was much astonished, but his minister said:

“I suspect, my lord, this is some Ṛṣi of ancient days become a parrot on account of a curse, but owing to his piety he remembers his former birth, and so recollects what he formerly read.”

When the ministers said this to the king, the king said to the parrot:

“I feel curiosity, my good parrot, tell me your story. Where is your place of birth? How comes it that in your parrot condition you know the Śāstras? Who are you?”

Then the parrot shed tears, and slowly spoke:

“The story is sad to tell, O King, but listen, I will tell it in obedience to thy command.

83a. The Parrot’s Account of his own Life as a Parrot

Near the Himalayas, O King, there is a rohinī tree, which resembles the Vedas, in that many birds take refuge in its branches that extend through the heaven, as Brāhmans in the various branches of the sacred tradition.[3] There a cock-parrot used to dwell with his hen, and to that pair I was born, by the influence of my evil works in a former life. And as soon as I was born, the hen-parrot, my mother, died, but my old father put me under his wing and fostered me tenderly. And he continued to live there, eating what remained over from the fruits brought by the other parrots, and giving some to me.

Once on a time there came there to hunt a terrible army of Bhillas, making a noise with cow’s horns strongly blown; and the whole of that great wood was like an army fleeing in rout, with terrified antelopes for dust-stained banners, and the bushy tails of the camarī deer, agitated in fear, resembling chowries, as the host of Pulindas rushed upon it to slay various living creatures. And after the army of Śavaras had spent the day in the hunting-grounds, in the sport of death, they returned with the loads of flesh which they had obtained. But a certain aged Śavara, who had not obtained any flesh, saw the tree in the evening, and being hungry, approached it, and he quickly climbed up it, and kept dragging parrots and other birds from their nests, killing them, and flinging them on the ground. And when I saw him coming near, like the minister of Yama, I slowly crept in fear underneath the wing of my father. And in the meanwhile the ruffian came near our nest, and dragged out my father, and wringing his neck, flung him down on the ground at the foot of the tree. And I fell with my father, and slipping out from underneath his wing, I slowly crept in my fear into the grass and leaves. Then the rascally Bhilla came down, and roasted some of the parrots and ate them, and others he carried off to his own village.

Then my fear was at an end, but I spent a night long from grief, and in the morning, when the flaming eye[4] of the world had mounted high in the heaven, I, being thirsty, went to the bank of a neighbouring lake full of lotuses, tumbling frequently, clinging to the earth with my wings, and there I saw on the sand of the lake a hermit, named Marīci, who had just bathed, as it were my good works in a former state of existence. He, when he saw me, refreshed me with drops of water flung in my face, and, putting me in the hollow of a leaf, out of pity, carried me to his hermitage.

There Pulastya, the head of the hermitage, laughed when he saw me, and being asked by the other hermits why he laughed, having supernatural insight, he said:

“When I beheld this parrot, who is a parrot in consequence of a curse, I laughed[5] out of sorrow, but after I have said my daily prayer I will tell a story connected with him, which shall cause him to remember his former birth, and the occurrences of his former lives.”

After saying this, the hermit Pulastya rose up for his daily prayer, and, after he had performed his daily prayer, being again solicited by the hermits, the great sage told this story concerning me.

83aa. The Hermit’s Story of Somaprabha, Manorathaprabhā, and Makarandikā, wherein it appears who the Parrot was in a Former Birth

There lived in the city of Ratnākara a king named Jyotiṣprabha, who ruled the earth with supreme authority, as far as the sea, the mine of jewels. There was born to him, by his queen named Harṣavatī, a son, whose birth was due to the favour of Śiva propitiated by severe asceticism. Because the queen saw in a dream the moon entering her mouth,[6] the king gave his son the name of Somaprabha. And the prince gradually grew up with ambrosial qualities, furnishing a feast to the eyes of the subjects.

And his father Jyotiṣprabha, seeing that he was brave, young, beloved by the subjects, and able to bear the weight of empire, gladly anointed him Crown Prince. And he gave him as minister the virtuous Priyaṅkara, the son of his own minister named Prabhākara. On that occasion Mātali descended from the heaven with a celestial horse, and coming up to Somaprabha, said to him:

“You are a Vidyādhara, a friend of Indra’s, born on earth, and he has sent you an excellent horse named Āśuśravas, the son of Ucchaiḥśravas, in memory of his former friendship; if you mount it you will be invincible by your foes.”

After the charioteer of Indra had said this, he gave Somaprabha that splendid horse, and after receiving due honour, he flew up to heaven again.

Then Somaprabha spent that day pleasantly in feasting, and the next day said to his father, the king:

“My father, the duty of a Kṣatriya is not complete without a desire for conquest, so permit me to march out to the conquest of the regions.”

When his father Jyotiṣprabha heard that, he was pleased, and consented, and made arrangements for his expedition. Then Somaprabha bowed before his father, and marched out on an auspicious day, with his forces, for the conquest of the regions, mounted on the horse given by Indra. And by the help of his splendid horse he conquered the kings of every part of the world, and, being irresistible in might, he stripped them of their jewels. He bent his bow and the necks of his enemies at the same time; the bow was unbent again, but the heads of his enemies were never again uplifted.

Then, as he was returning in triumph, on a path which led him near the Himālayas, he made his army encamp, and went hunting in a wood. And as chance would have it, he saw there a Kinnara, made of a splendid jewel,[7] and he pursued him on his horse given by Indra, with the object of capturing him. The Kinnara entered a cavern in the mountain, and was lost to view, but the prince was carried far away by that horse.

And when the sun, after diffusing illumination over the quarters of the world, had reached the western peak, where he meets the evening twilight, the prince, being tired, managed, though with difficulty, to return, and he beheld a great lake, and wishing to pass the night on its shores, he dismounted from his horse. And after he had given grass and water to the horse, and had taken fruits and water himself, and felt rested, he suddenly heard from a certain quarter the sound of a song. Out of curiosity he went in the direction of the sound, and saw at no great distance a heavenly nymph, singing in front of a liṅga of Śiva.

He said to himself in astonishment:

“Who may this lovely one be?”

And she, seeing that he was of noble appearance, said to him bashfully:

“Tell me, who are you? How did you reach alone this inaccessible place?”

When he heard this, he told the story, and asked her in turn:

“Tell me, who are you and what is your business in this wood?”

When he asked this question, the heavenly maiden said:

“If you have any desire, noble sir, to hear my tale, listen, I will tell it.”

After this preface she began to speak with a gushing flood of tears.

83aaa. Manorathaprabhā and Raśmimat

There is here, on the table-land of the Himālayas, a city named Kāñcanābha, and in it there dwells a king of the Vidyādharas named Padmakūṭa. Know that I am the daughter of that king by his Queen Hemaprabhā, and that my name is Manorathaprabhā, and my father loves me more than his life. I, by the power of my science, used to visit, with my female companions, the isles, and the principal mountains, and the woods, and the gardens, and after amusing myself, I made a point of returning every day at my father’s meal-time, at the third watch of the day, to my palace.

Once on a time I arrived here as I was roaming about, and I saw on the shore of the lake a hermit’s son with his companion. And being summoned by the splendour of his beauty, as if by a female messenger, I approached him, and he welcomed me with a wistful look.

And then I sat down, and my friend, perceiving the feelings of both, put this question to him through his companion:

“Who are you, noble sir, tell me?”

And his companion said:

“Not far from here, my friend, there lives in a hermitage a hermit named Dīdhitimat. He, being subject to a strict vow of chastity, was seen once, when he came to bathe in this lake, by the goddess Śrī, who came there at the same time. As she could not obtain him in the flesh, as he was a strict ascetic, and yet longed for him earnestly with her mind, she conceived a mind-born son.

And she took that son to Dīdhitimat, saying to him:

‘I have obtained this son by looking at you; receive it.’

And after giving the son to the hermit, Śrī disappeared. And the hermit gladly received the son, so easily obtained, and gave him the name of Raśmimat, and gradually reared him, and after investing him with the sacred thread, taught him out of love all the sciences. Know that you see before you in this young hermit that very Raśmimat, the son of Śrī, come here with me on a pleasure journey.”

When my friend had heard this from the youth’s friend, she, being questioned by him in turn, told my name and descent as I have now told it to you.

Then I and the hermit’s son became still more in love with one another from hearing one another’s descent, and while we were lingering there, a second attendant came and said to me:

“Rise up; your father, fair one, is waiting for you in the dining-room of the palace.”

When I heard that, I said, “I will return quickly,” and leaving the youth there, I went into the presence of my father out of fear. And when I came out, having taken a very little food, the first attendant came to me and said of her own accord:

“The friend of that hermit’s son came here, my friend, and standing at the gate of the court, said to me in a state of hurried excitement: ‘Raśmimat has sent me here now, bestowing on me the power of travelling in the air, which he inherits from his father, to see Manorathaprabhā: he is reduced to a terrible state by love and cannot retain his breath a moment longer without that mistress of his life.’”

The moment I heard this, I left my father’s palace, and, accompanied by that friend of the hermit’s son, who showed me the way, and my attendant, I came here; and when I arrived here, I saw that that hermit’s son, separated from me, had resigned, at the rising of the moon, the nectar of his life.

So I, grieved by separation from him, was blaming my vital frame, and longing to enter the fire with his body. But at that very moment a man, with a body like a mass of flame, descended from the sky, and flew up to heaven with his body.

Then I was desirous to hurl myself into the fire alone, but at that moment a voice issued from the air here:

“Manorathaprabhā, do not do this thing, for at the appointed time thou shalt be reunited to this thy hermit’s son.”

On hearing this, I gave up the idea of suicide, and here I remain full of hope, waiting for him, engaged in the worship of Śiva. And as for the friend of the hermit’s son, he has disappeared somewhere.

83 aa. The Hermit's Story of Somaprabha, Manorathaprabhā and Makarandikā, wherein it appears who the Parrot was in a Former Birth

When the Vidyādhara maiden had said this, Somaprabha said to her:

“Then why do you remain alone; where is that female attendant of yours?”

When the Vidyādhara maiden heard this, she answered:

“There is a king of the Vidyādharas, named Siṃhavikrama, and he has a matchless daughter named Makarandikā; she is a friend of mine, dear as my life, who sympathises with my grief, and she to-day sent her attendant to learn tidings of me. So I sent back my own attendant to her, with her attendant; it is for that reason that I am at present alone.”

As she was saying this, she pointed out to Somaprabha her attendant descending from heaven. And she made the attendant, after she had told her news, strew a bed of leaves for Somaprabha, and also give grass to his horse.

Then, after passing the night, they rose up in the morning, and saw approaching a Vidyādhara, who had descended from heaven. And that Vidyādhara, whose name was Devajaya, after sitting down, spoke thus to Manorathaprabhā:

“Manorathaprabhā, King Siṃhavikrama informs you that your friend, his daughter Makarandikā, out of love for you, refuses to marry until you have obtained a bridegroom. So he wishes you to go there and admonish her, that she may be ready to marry.”

When the Vidyādhara maiden heard this, she prepared to go, out of regard for her friend, and then Somaprabha said to her:

“Virtuous one, I have a curiosity to see the Vidyādhara world; so take me there, and let my horse remain here supplied with grass.”

When she heard that, she consented, and taking her attendant with her, she flew through the air, with Somaprabha, who was carried in the arms of Devajaya.

When she arrived there, Makarandikā welcomed her, and seeing Somaprabha, asked: “Who is this?”

And when Manorathaprabhā told his story, the heart of Makarandikā was immediately captivated by him. He, for his part, thought in his mind, deeming he had come upon Good Fortune in bodily form:

“Who is the fortunate man destined to be her bridegroom?”

Then, in confidential conversation, Manorathaprabhā put the following question to Makarandikā:

“Fair one, why do you not wish to be married?”

And she, when she heard this, answered:

“How could I desire marriage until you have accepted a bridegroom, for you are dearer to me than life?”

When Makarandikā said this, in an affectionate manner, Manorathaprabhā said:

“I have chosen a bridegroom, fair one; I am waiting here in hopes of union with him.”

When she said this, Makarandikā said:

“I will do as you direct.”[8]

Then Manorathaprabhā, seeing the real state of her feelings, said to her:

“My friend Somaprabha has come here as your guest, after wandering through the world, so you must entertain him as a guest with becoming hospitality.”

When Makarandikā heard this, she said:

“I have already bestowed on him, by way of hospitality, everything but myself, but let him accept me, if he is willing.”

When she said this, Manorathaprabhā told their love to her father, and arranged a marriage between them.

Then Somaprabha recovered his spirits, and, delighted, said to her:

“I must go now to your hermitage, for possibly my army, commanded by my minister, may come there, tracking my course, and if they do not find me they may return, suspecting something untoward. So I will depart, and after I have learned the tidings of the host I will return, and certainly marry Makarandikā on an auspicious day.”

When Manorathaprabhā heard that, she consented, and took him back to her own hermitage, making Devajaya carry him in his arms.

In the meanwhile his minister Priyaṅkara came there with the army, tracking his footsteps. And while Somaprabha, in delight, was recounting his adventures to his minister, whom he met there, a messenger came from his father with a written message that he was to return quickly. Then, by the advice of his minister, he went with his army back to his own city, in order not to disobey his father’s command, and as he started he said to Manorathaprabhā and Devajaya: “I will return as soon as I have seen my father.”

Then Devajaya went and informed Makarandikā of that, and in consequence she became afflicted with the sorrow of separation. She took no pleasure in the garden, nor in singing, nor in the society of her ladies-in-waiting, nor did she listen to the amusing voices of the parrots; she did not take food; much less did she care about adorning herself. And though her parents earnestly admonished her, she did not recover her spirits. And she soon left her couch of lotus-fibres, and wandered about like an insane woman, causing distress to her parents.

And when she would not listen to their words, though they tried to console her, her parents in their anger pronounced this curse on her:

“You shall fall for some time among the unfortunate race of the Niṣādas, with this very body of yours, without the power of remembering your former birth.”

When thus cursed by her parents, Makarandikā entered the house of a Niṣāda, and became that very moment a Niṣāda maiden. And her father Siṃhavikrama, the king of the Vidyādharas, repented, and through grief for her died, and so did his wife. Now that king of the Vidyādharas was in a former birth a Ṛṣi who knew all the Śāstras, but now on account of some remnant of former sin he has become this parrot, and his wife also has been born as a wild sow, and this parrot, owing to the power of former austerities, remembers what it learned in a former life.

83a. The Parrot’s Account of his own Life as a Parrot

“So I laughed,[9] considering the marvellous results of his works. But he shall be released as soon as he has told this tale in the court of a king. And Somaprabha shall obtain the parrot’s daughter in his Vidyādhara birth, Makarandikā, who has now become a Niṣāda female. And Manorathaprabhā also shall obtain the hermit’s son Raśmimat, who has now become a king; but Somaprabha, as soon as he had seen his father, returned to her hermitage, and remains there propitiating Śiva in order to recover his beloved.”

When the hermit Pulastya had said thus much, he ceased, and I remembered my former birth, and was plunged in grief and joy. Then the hermit Marīci, who carried me out of pity to the hermitage, took me and reared me. And when my wings grew I flew hither and thither with the flightiness natural to a bird,[10] displaying the miracle of my learning. And falling into the hands of a Niṣāda, I have in course of time reached your court. And now my evil works have spent their force, having been brought with me into the body of a bird.

83. Story of King Sumanas, the Niṣāda Maiden and the Learned Parrot

When the learned and eloquent parrot had finished this tale in the presence of the court, King Sumanas suddenly felt his soul filled with astonishment, and disturbed with love. In the meanwhile Śiva, being pleased, said to Somaprabha in a dream:

“Rise up, King, and go into the presence of King Sumanas; there thou wilt find thy beloved. For the maiden, named Makarandikā, has become, by the curse of her father, a Niṣāda maiden, named Muktālatā, and she has gone with her own father, who has become a parrot, to the court of the king. And when she sees thee, her curse will come to an end, and she will remember her existence as a Vidyādhara maiden, and then a union will take place between you, the joy of which will be increased by your recognising one another.”

Having said this to that king, Śiva, who is merciful to all his worshippers, said to Manorathaprabhā, who was also living in his hermitage:

“The hermit’s son Raśmimat, whom thou didst accept as thy bridegroom, has been born again under the name of Sumanas, so go to him and obtain him, fair one; he will at once remember his former birth when he beholds thee.”

So Somaprabha and the Vidyādhara maiden, being separately commanded in a dream by Śiva, went immediately to the court of that Sumanas. And there Makarandikā, on beholding Somaprabha, immediately remembered her former birth, and being released from her long curse, and recovering her heavenly body, she embraced him. And Somaprabha, having by the favour of Śiva obtained that daughter of the Vidyādhara prince, as if she were the incarnate fortune of heavenly enjoyment, embraced her, and considered himself to have attained his object. And King Sumanas, having beheld Manorathaprabhā, remembered his former birth, and entered his former body, that fell from heaven, and became Raśmimat, the son of the chief of hermits. And once more united with his beloved, for whom he had long yearned, he entered his own hermitage, and King Somaprabha departed with his beloved to his own city. And the parrot, too, left the body of a bird, and went to the home earned by his asceticism.

[M] (Main story line continued)

“Thus you see that the appointed union of human beings certainly takes place in this world, though vast spaces intervene.”

When Naravāhanadatta heard this wonderful, romantic and agreeable story from his own minister Gomukha, as he was longing for Śaktiyaśas, he was much pleased.

[Additional note: on the story of king Sumanas]

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

I.e. 4,320,000 years. It is more correctly known as a Mahāyuga, one thousand of which make a Kalpa. Thus a Kalpa is 4320 million years, and not 432 million as wrongly stated by Tawney in Vol. II, pp. 139n1, 163n2, where I should have corrected it. See further Vol. IV, pp. 240n1, 241n.— N.M.P.

[2]:

Cf. the falcon in Chaucer’s “Squire’s Tale,” and the parallels quoted by Skeat in his Introduction to the “Prioress’s Tale.. p. xlvii.——See W. Crooke, Popular Religion and Folk-Lore of Northern India, vol. ii, p. 252, and the note at the end of this chapter.— n.m.p.

[3]:

An elaborate pun on dvija and śākhā.

[4]:

For the conception of the sun as an eye see Kuhn, Die Herabkunft des Feuers und des Göttertranks, pp. 52, 53. The idea is common in English poetry. See for instance Milton, Paradise Lost, v, 171; Spenser’s Faerie Queene, i, 3,4. For instances in classical poetry see Ovid, Metamorphoses, iv, 228; Aristophanes, Nubes, 286; Sophocles, Trachiniæ, 101.

[5]:

See Vol. I, pp. 4 6n2, 47n.— n.m.p.

[6]:

See Crooke, op. cit., vol. i, p. 14.— n.m.p.

[7]:

The D. text read sad-ratna-khachitam —“studded with goodly gems.”— n.m.p.

[8]:

I read tvadvākyam with the Sanskrit College MS. and ahitāśaṅki tacca in śl. 141 with the same MS.——So in the D. text.—n.m.p.

[9]:

See Bloomfield, Amer. Orient. Soc., vol. xxxvi, p. 80.—n.m.p.

[10]:

Cf. Aristophanes, Aves, 11. 169, 170:

ἄνθρωπος ὄρνις ἀστάθμητος, πετόμενος,

ἀτέκμαρτος, οὐδέποτ’ ἐν ταὐτῷ μένων