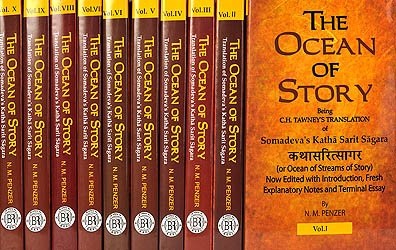

Kathasaritsagara (the Ocean of Story)

by Somadeva | 1924 | 1,023,469 words | ISBN-13: 9789350501351

This is the English translation of the Kathasaritsagara written by Somadeva around 1070. The principle story line revolves around prince Naravāhanadatta and his quest to become the emperor of the Vidhyādharas (‘celestial beings’). The work is one of the adoptations of the now lost Bṛhatkathā, a great Indian epic tale said to have been composed by ...

Chapter LX

[M] (main story line continued) THEN the chief minister Gomukha, having told the story of the two Vidyādhara maidens, said to Naravāhanadatta:

“Some ordinary men even, being kindly disposed towards the three worlds, resist with firm resolution the disturbance of love and other passions.

“For the King Kuladhara once had a servant of distinguished valour, a young man of good family, named Śūravarman. And one day, as he was returning from war, he entered his house suddenly, and found his wife alone with his friend. And when he saw it, he restrained his wrath, and in his self-control reflected:

‘What is the use of slaying this animal who has betrayed his friend? Or of punishing this wicked woman? Why, too, should I saddle my soul with a load of guilt?’

After he had thus reflected, he left them both unharmed and said to them:

‘I will kill whichever of you two I see again. You must neither of you come in my sight again.’

When he said this and let them depart, they went away to some distant place, but Śūravarman married another wife, and lived there in comfort.

“Thus, Prince, a man who conquers wrath will not be subject to grief; and a man who displays prudence is never harmed. Even in the case of animals prudence produces success, not valour. In proof of it, hear this story about the lion and the bull and other animals.

[also see notes on the Pañcatantra of Somadeva]

84. Story of the Bull abandoned in the Forest [1]

There was in a certain city a rich merchant’s son. Once on a time, as he was going to the city of Mathurā to trade, a draught-bull belonging to him, named Sañjīvaka, as it was dragging the yoke vigorously, broke it, and so slipped in the path, which had become muddy by a mountain torrent flowing into it, and fell and bruised its limbs. The merchant’s son, seeing that the bull was unable to move on account of its bruises, and not succeeding in his attempts to raise it up from the ground, at last in despair went off and left it there. And, as fate would have it, the bull slowly revived, and rose up, and by eating tender grass recovered from its former condition. And it went to the bank of the Yamunā, and by eating green grass and wandering about at will it became fat and strong. And it roamed about there, with full hump, wantoning, like the bull of Śiva, tearing up ant-hills with its horns, and bellowing frequently.

Now at that time there lived in a neighbouring wood a lion named Piṅgalaka, who had subdued the forest by his might; and that king of beasts had two jackals for ministers: the name of the one was Damanaka, and the name of the other was Karaṭaka. That lion, going one day to the bank of the Yamunā to drink water, heard close to him the roar of that bull Sañjīvaka.

And when the lion heard the roar of that bull, never heard before, resounding through the air, he thought:

“What animal makes this sound? Surely some great creature dwells here, so I will depart, for if it saw me it might slay me, or expel me from the forest.”

Thereupon the lion quickly returned to the forest without drinking water, and continued in a state of fear, hiding his feelings from his followers.

Then the wise jackal[2] Damanaka, the minister of that king, said secretly to Karaṭaka, the second minister:

“Our master went to drink water; so how comes it that he has so quickly returned without drinking? We must ask him the reason.”

Then Karaṭaka said:

“What business is this of ours? Have you not heard the story of the ape that drew out the wedge?

84a. The Monkey that pulled out the Wedge [3]

In a certain town a merchant had begun to build a temple to a divinity and had accumulated much timber. The workmen there, after sawing through the upper portion of a plank, placed a wedge in it, and leaving it thus suspended, went home. In the meanwhile a monkey came there and bounded up out of mischief, and sat on the plank, the halves of which were separated by the wedge. And he sat over the gap between the two halves, as if in the mouth of death, and in purposeless mischief pulled out the wedge. Then he fell with the plank, the wedge of which had been pulled out, and was killed, having his parts crushed by the flying together of the separated halves.

84. Story of the Bull abandoned in the Forest

“Thus a person is ruined by meddling with what is not his own business. So what is the use of our penetrating the mind of the king of beasts?”

When the grave Damanaka heard Karaṭaka say this, he answered:

“Certainly wise ministers must penetrate and observe the peculiarities of their master’s character. For who would confine his attention to filling his belly?”

When Damanaka said this, the good Karaṭaka said:

“Prying for one’s own gratification is not the duty of a servant.”

Damanaka, being thus addressed, replied:

“Do not speak thus; everyone desires a recompense suited to his character: the dog is satisfied with a bone only, the lion attacks an elephant.”

When Karaṭaka heard this, he said:

“And supposing under these circumstances the master is angry, instead of being pleased, where is your special advantage? Lords, like mountains, are exceedingly rough, firm, uneven, difficult of access, and surrounded with noxious creatures.”

Then Damanaka said:

“This is true; but he who is wise gradually gets influence over his master by penetrating his character.”

Then Karaṭaka said: “Well, do so”; and Damanaka went into the presence of his master the lion.

The lion received him kindly: so he bowed, and sat down, and immediately said to him:

“King, I am an hereditary useful servant of yours. One useful is to be sought after, though a stranger, but a mischievous one is to be abandoned: a cat, being useful, is bought with money, brought from a distance, and cherished; but a mouse, being harmful, is carefully destroyed, though it has been nourished up in one’s house. And a king who desires prosperity must listen to servants who wish him well, and they must give their lord at the right time useful counsel, even without being asked. So, King, if you feel confidence in me, if you are not angry, and if you do not wish to conceal your feelings from me, and if you are not disturbed in mind by my boldness, I would ask you a certain question.”

When Damanaka said this, the lion Piṅgalaka answered:

“You are trustworthy, you are attached to me, so speak without fear.”

When Piṅgalaka said this, Damanaka said:

“King, being thirsty, you went to drink water; so why did you return without drinking, like one despondent?”

When the lion heard this speech of his, he reflected:

“I have been discovered by him, so why should I try to hide the truth from this devoted servant?”

Having thus reflected, he said to him:

“Listen, I must not hide anything from you. When I went to drink water, I heard there a noise which I never heard before, and I think it is the terrible roar of some animal superior to myself in strength. For, as a general rule, the might of creatures is proportionate to the sound they utter, and it is well known that the infinitely various animal creation has been made by God in regular gradations. And now that he has entered here I cannot call my body nor my wood my own; so I must depart hence to some other forest.”

When the lion said this, Damanaka answered him:

“Being valiant, O King, why do you wish to leave the wood for so slight a reason? Water breaks a bridge, secret whisperings friendship, counsel is ruined by garrulity, cowards only are routed by a mere noise. There are many noises, such as those of machines, which are terrible till one knows the real cause. So your Highness must not fear this. Hear by way of illustration the story of the jackal and the drum.

84b. The Jackal and the Drum [4]

Long ago there lived a jackal in a certain forest district. He was roaming about in search of food, and came upon a plot of ground where a battle had taken place, and hearing from a certain quarter a booming sound, he looked in that direction. There he saw a drum lying on the ground, a thing with which he was not familiar.

He thought:

“What kind of animal is this, that makes such a sound?”

Then he saw that it was motionless, and coming up and looking at it, he came to the conclusion that it was not an animal. And he perceived that the noise was produced by the parchment being struck by the shaft of an arrow, which was moved by the wind. So the jackal laid aside his fear, and he tore open the drum, and went inside, to see if he could get anything to eat in it, but lo! it was nothing but wood and parchment.

84. Story of the Bull abandoned in the Forest

“So, King, why do creatures like you fear a mere sound? If you approve, I will go there to investigate the matter.”

When Damanaka said this, the lion answered:

“Go there, by all means, if you dare.”

So Damanaka went to the bank of the Yamunā. While he was roaming slowly about there, guided by the sound, he discovered that bull eating grass. So he went near him, and made acquaintance with him, and came back, and told the lion the real state of the case. The lion Piṅgalaka was delighted, and said:

“If you have really seen that great bull, and made friends with him, bring him here by some artifice, that I may see what he is like.”

So he sent Damanaka back to that bull. Damanaka went to the bull, and said:

“Come! Our master, the king of beasts, is pleased to summon you.”

But the bull would not consent to come, for he was afraid.

Then the jackal again returned to the forest, and induced his master the lion to grant the bull assurance of protection. And he went and encouraged Sañjīvaka with this promise of protection, and so brought him into the presence of the lion.

And when the lion saw him come and bow before him, he treated him with politeness, and said:

“Remain here now about my person, and entertain no fear.”

And the bull consented, and gradually gained such an influence over the lion that he turned his back on his other dependents, and was entirely governed by the bull.

Then Damanaka, being annoyed, said to Karaṭaka in secret:

“See! our master has been taken possession of by Sañjīvaka, and does not trouble his head about us. He eats his flesh alone, and never gives us a share. And the fool is now taught his duty by this bull.[5] It was I that caused all this mischief by bringing this bull. So I will now take steps to have him killed, and to reclaim our master from his unbecoming infatuation.”

When Karaṭaka heard this from Damanaka, he said:

“Friend, even you will not be able to do this now.”

Then Damanaka said:

“I shall certainly be able to accomplish it by prudence. What can he not do whose prudence does not fail in calamity? As a proof, hear the story of the makara[6] that killed the crane.[7]

84c. The Crane and the Makara [8]

Of old time there dwelt a crane in a certain tank rich in fish; and the fish in terror used to flee out of his sight. Then the crane, not being able to catch the fish, told them a lying tale:

“There has come here a man with a net who kills fish. He will soon catch you with a net and kill you. So act on my advice, if you repose any confidence in me. There is in a lonely place a translucent lake; it is unknown to the fishermen of these parts; I will take you there one by one, and drop you into it, that you may live there.”

When those foolish fish heard that, they said in their fear:

“Do so; we all repose confidence in you.”

Then the treacherous crane took the fish away one by one, and, putting them down on a rock, devoured in this way many of them.

Then a certain makara dwelling in that lake, seeing him carrying off fish, said:

“Whither are you taking the fish?”

Then that crane said to him exactly what he had said to the fish. The makara,[9] being terrified, said:

“Take me there too.”

The crane’s intellect was blinded with the smell of his flesh, so he took him up, and soaring aloft carried him towards the slab of rock. But when the makara got near the rock he saw the fragments of the bones of the fish that the crane had eaten, and he perceived that the crane was in the habit of devouring those who reposed confidence in him. So no sooner was the sagacious makara put down on the rock than with complete presence of mind he cut off the head of the crane. And he returned and told the occurrence, exactly as it happened, to the other fish, and they were delighted, and hailed him as their deliverer from death.

84. Story of the Bull abandoned in the Forest

“Prudence indeed is power, so what has a man, devoid of prudence, to do with power? Hear this other story of the lion and the hare.

84d. The Lion and the Hare [10]

There was in a certain forest a lion, who was invincible, and sole champion of it, and whatever creatures he saw in it he killed. Then all the animals, deer and all, met and deliberated together, and they made the following petition to that king of beasts:—

“Why by killing us all at once do you ruin your own interests? We will send you one animal every day for your dinner.”

When the lion heard this, he consented to their proposal, and as he was in the habit of eating one animal every day, it happened that it was one day the lot of a hare to present himself to be eaten.

The hare was sent off by the united animals, but on the way the wise creature reflected:

“He is truly brave who does not become bewildered even in the time of calamity; so, now that Death stares me in the face, I will devise an expedient.”

Thus reflecting, the hare presented himself before the lion late. And when he arrived after his time, the lion said to him:

“Hola! how is this that you have neglected to arrive at my dinner hour, or what worse penalty than death can I inflict on you, scoundrel?”

When the lion said this, the hare bowed before him, and said:

“It is not my fault, your Highness; I have not been my own master to-day, for another lion detained me on the road, and only let me go after a long interval.”

When the lion heard that, he lashed his tail, and his eyes became red with anger, and he said:

“Who is that second lion? Show him me.”

The hare said:

“Let your Majesty come and see him.”

The lion consented, and followed him. Thereupon the hare took him away to a distant well. “Here he lives, behold him,” said the hare, and when thus addressed by the hare, the lion looked into the well, roaring all the while with anger. And seeing his own reflection in the clear water, and hearing the echo of his own roar, thinking that there was a rival lion there roaring louder than himself,[11] he threw himself in a rage into the well, in order to kill him, and there the fool was drowned. And the hare, having himself escaped death by his wisdom, and having delivered all the animals from it, went and delighted them by telling his adventure.

84. Story of the Bull abandoned in the Forest

“So you see that wisdom is the supreme power, not strength, since by virtue of it even a hare killed a lion. So I will effect my object by wisdom.”

When Damanaka said this, Karaṭaka remained silent.

Then Damanaka went and remained in the presence of the King Piṅgalaka, in a state of assumed depression. And when Piṅgalaka asked him the reason, he said to him in a confidential aside:

“I will tell you, King, for if one knows anything one ought not to conceal it. And one should speak too without being commanded to do so, if one desires the welfare of one’s master. So hear this representation of mine, and do not suspect me. This bull Sañjīvaka intends to kill you and gain possession of the kingdom, for in his position of minister he has come to the conclusion that you are timid; and longing to slay you, he is brandishing his two horns, his natural weapons, and he talks over the animals in the forest, encouraging them with speeches of this kind: ‘We will kill by some artifice this flesh-eating king of beasts, and then you can live in security under me, who am an eater of herbs only.’ So think about this bull; as long as he is alive there is no security for you.”

When Damanaka said this, Piṅgalaka answered:

“What can that miserable herb-eating bull do against me? But how can I kill a creature that has sought my protection, and to whom I have promised immunity from injury?”

When Damanaka heard this, he said:

“Do not speak so. When a king makes another equal to himself, Fortune does not proceed as favourably as before.[12] The fickle goddess, if she places her feet at the same time upon two exalted persons, cannot keep her footing long; she will certainly abandon one of the two. And a king who hates a good servant and honours a bad servant is to be avoided by the wise, as a wicked patient by physicians. Where there is a speaker and a hearer of that advice, which in the beginning is disagreeable, but in the end is useful, there Fortune sets her foot. He who does not hear the advice of the good, but listens to the advice of the bad, in a short time falls into calamity, and is afflicted. So what is the meaning of this love of yours for the bull, O King? And what does it matter that you gave him protection, or that he came as a suppliant, if he plots against your life? Moreover, if this bull remains always about your person, you will have worms produced in you by his excretions. And they will enter your body, which is covered with the scars of wounds from the tusks of infuriated elephants. Why should he not have chosen to kill you by craft? If a wicked person is wise enough not to do an injury[13] himself, it will happen by association with him. Hear a story in proof of it.

84e. The Lome and the Flea [14]

In the bed of a certain king there long lived undiscovered a louse, that had crept in from somewhere or other, by name Mandavisarpiṇī. And suddenly a flea, named Ṭiṭṭibha, entered that bed, wafted there by the wind from some place or other.

And when Mandavisarpiṇī saw him, she said:

“Why have you invaded my home? Go elsewhere.”

Ṭiṭṭibha answered:

“I wish to drink the blood of a king, a luxury which I have never tasted before, so permit me to dwell here.”

Then, to please him, the louse said to him:

“If this is the case, remain. But you must not bite the king, my friend, at unseasonable times; you must bite him gently when he is asleep.”

When Ṭiṭṭibha heard that, he consented, and remained. But at night he bit the king hard when he was in bed, and then the king rose up, exclaiming:

“I am bitten.”

Then the wicked flea fled quickly, and the king’s servants made a search in the bed, and finding the louse there, killed it.

84. Story of the Bull abandoned in the Forest

“So Mandavisarpiṇī perished by associating with Ṭiṭṭibha. Accordingly your association with Sañjīvaka will not be for your advantage. If you do not believe in what I say, you will soon yourself see him approach, brandishing his head, confiding in his horns, which are sharp as lances.”

By these words the feelings of Piṅgalaka were changed towards the bull, and so Damanaka induced him to form in his heart the determination that the bull must be killed. And Damanaka, having ascertained the state of the lion’s feelings, immediately went off of his own accord to Sañjīvaka, and sat in his presence with a despondent air.

The bull said to him:

“Friend, why are you in this state? Are you in good health?”

The jackal answered:

“What can be healthy with a servant? Who is permanently dear to a king? What petitioner is not despised? Who is not subject to time?”

When the jackal said this, the bull again said to him:

“Why do you seem so despondent to-day, my friend, tell me?”

Then Damanaka said:

“Listen; I speak out of friendship. The lion Piṅgalaka has to-day become hostile to you. So unstable is his affection that, without regard for his friendship, he wishes to kill you and eat you, and I see that his evilly disposed courtiers have instigated him to do it.”

The simple-minded bull, supposing, on account of the confidence he had previously reposed in the jackal, that this speech was true, and feeling despondent, said to him:

“Alas, a mean master, with mean retainers, though he be won over by faithful service, becomes estranged. In proof of it, hear this story.

84f. The Lion, the Panther, the Crow and the Jackal [15]

There lived once in a certain forest a lion, named Madotkaṭa, and he had three followers, a panther, a crow and a jackal. That lion once saw a camel, that had escaped from a caravan, entering his wood, a creature he was not familiar with before, of ridiculous appearance.

That king of beasts said in astonishment: “What is this creature?”

And the crow, who knew when it behoved him to speak,[16] said: “It is a camel.”

Then the lion, out of curiosity, had the camel summoned, and giving him a promise of protection, he made him his courtier, and placed him about his person.

One day the lion was wounded in a fight with an elephant, and being out of health, made many fasts, though surrounded by those attendants who were in good health. Then the lion, being exhausted, roamed about in search of food, but not finding any, secretly asked all his courtiers, except the camel, what was to be done.

They said to him:

“Your Highness, we must give advice which is seasonable in our present calamity. What friendship can you have with a camel, and why do you not eat him? He is a grass-eating animal, and therefore meant to be devoured by us flesh-eaters. And why should not one be sacrificed to supply food to many? If your Highness should object, on the ground that you cannot slay one to whom you have granted protection, we will contrive a plot by which we shall induce the camel himself to offer you his own body.”

When they had said this, the crow, by the permission of the lion, after arranging the plot, went and said to that camel:

“This master of ours is overpowered with hunger, and says nothing to us, so we intend to make him well disposed to us by offering him our bodies, and you had better do the same, in order that he may be well disposed towards you.”

When the crow said this to the camel, the simple-minded camel agreed to it, and came to the lion with the crow.

Then the crow said: “King, eat me, for I am my own master.”

Then the lion said: “What is the use of eating such a small creature as you?”

Thereupon the jackal said: “Eat me.” And the lion rejected him in the same way.

Then the panther said: “Eat me.” And yet the lion would not eat him.

And at last the camel said: “Eat me.”

So the lion and the crow and his fellows entrapped him by these deceitful offers, and taking him at his word, killed him, divided him into portions, and ate him.

84. Story of the Bull abandoned in the Forest

“In the same way some treacherous person has instigated Piṅgalaka against me without cause. So now Destiny must decide. For it is better to be the servant of a vulture-king with swans for courtiers, than to serve a swan as king, if his courtiers be vultures, much less a king of a worse character, with such courtiers.”[17]

When the dishonest Damanaka heard Sañjīvaka say that, he replied:

“Everything is accomplished by resolution. Listen, I will tell you a tale to prove this.

84g. The Pair of Ṭiṭṭibhas [18]

There lived a certain cock ṭiṭṭibha on the shore of the sea with his hen. And the hen, being about to lay eggs, said to the cock:

“Come, let us go away from this place, for if I lay eggs here, the sea may carry them off with its waves.”

When the cock-bird heard this speech of the hen’s, he said to her:

“The sea cannot contend with me.”

On hearing that, the hen said:

“Do not talk so; what comparison is there between you and the sea? People must follow good advice, otherwise they will be ruined.

84gg. The Tortoise and the Two Swans [19]

For there was in a certain lake a tortoise, named Kambugrīva, and he had two swans for friends, Vikaṭa and Saṅkaṭa. Once on a time the lake was dried up by drought, and they wanted to go to another lake; so the tortoise said to them:

“Take me also to the lake you are desirous of going to.”

When the two swans heard this, they said to their friend the tortoise:

“The lake to which we wish to go is a tremendous distance off; but, if you wish to go there too, you must do what we tell you. You must take in your teeth a stick held by us, and while travelling through the air you must remain perfectly silent, otherwise you will fall and be killed.”

The tortoise agreed, and took the stick in his teeth, and the two swans flew up into the air, holding the two ends of it. And gradually the two swans, carrying the tortoise, drew near that lake, and were seen by some men living in a town below; and the thoughtless tortoise heard them making a chattering, while they were discussing with one another what the strange thing could be that the swans were carrying. So the tortoise asked the swans what the chattering below was about, and in doing so let go the stick from its mouth, and falling down to the earth, was there killed by the men.

84g. The Pair of Ṭiṭṭibhas

“Thus you see that a person who lets go common sense will be ruined, like the tortoise that let go the stick.” When the hen-bird said this, the cock-bird answered her:

“This is true, my dear; but hear this story also.

84ggg. The Three Fish

Of old time there were three fish in a lake near a river, one was called Anāgatavidhātri, a second Pratyutpannamati, and the third Yadbhaviṣya,[20] and they were companions. One day they heard some fishermen, who passed that way, saying to one another:

“Surely there must be fish in this lake.”

Thereupon the prudent Anāgatavidhātṛ, fearing to be killed by the fishermen, entered the current of the river and went to another place. But Pratyutpannamati remained where he was, without fear, saying to himself:

“I will take the expedient course if any danger should arise.”

And Yadbhaviṣya remained there, saying to himself:

“What must be, must be.”

Then those fishermen came and threw a net into that lake. But the cunning Pratyutpannamati, the moment he felt himself hauled up in the net, made himself rigid, and remained as if he were dead. The fishermen, who were killing the fish, did not kill him, thinking that he had died of himself, so he jumped into the current of the river, and went off somewhere else, as fast as he could. But Yadbhaviṣya, like a foolish fish, bounded and wriggled in the net, so the fishermen laid hold of him and killed him.

84g. The Pair of Ṭiṭṭibhas

“So I too will adopt an expedient when the time arrives; I will not go away through fear of the sea.” Having said this to his wife, the ṭiṭṭibha remained where he was, in his nest; and there the sea heard his boastful speech. Now, after some days, the hen-bird laid eggs, and the sea carried off the eggs with his waves, out of curiosity, saying to himself:

“I should like to know what this ṭiṭṭibha will do to me.”

And the hen-bird, weeping, said to her husband:

“The very calamity which I prophesied to you has come upon us.”

Then that resolute ṭiṭṭibha said to his wife:

“See what I will do to that wicked sea!”

So he called together all the birds, and mentioned the insult he had received, and went with them and called on the lord Garuḍa for protection. And the birds said to him:

“Though thou art our protector, we have been insulted by the sea as if we were unprotected, in that it has carried away some of our eggs.”

Then Garuḍa was angry, and appealed to Viṣṇu, who dried up the sea with the weapon of fire, and made it restore the eggs.

84. Story of the Bull abandoned in the Forest

“So you must be wise in calamity and not let go resolution. But now a battle with Piṅgalaka is at hand for you. When he shall erect his tail, and arise with his four feet together, then you may know that he is about to strike you. And you must have your head ready tossed up, and must gore him in the stomach, and lay your enemy low, with all his entrails tom out.”

After Damanaka had said this to the bull Sañjīvaka, he went to Karataka, and told him that he had succeeded in setting the two at variance.

Then Sañjīvaka slowly approached Piṅgalaka, being desirous of finding out the mind of that king of beasts by his face and gestures. And he saw that the lion was prepared to fight, being evenly balanced on all four legs, and having erected his tail, and the lion saw that the bull had tossed up his head in fear. Then the lion sprang on the bull and struck him with his claws, the bull replied with his horns, and so their fight went on.

And the virtuous Karaṭaka, seeing it, said to Damanaka:

“Why have you brought calamity on our master to gain your own ends? Wealth obtained by oppression of subjects, friendship obtained by deceit, and a lady-love gained by violence, will not remain long. But enough; whoever says much to a person who despises good advice, incurs thereby misfortune, as Sūcīmukha from the ape.

84h. The Monkeys, the Firefly and the Bird [21]

Once on a time there were some monkeys wandering in a troop in a wood. In the cold weather they saw a firefly and thought it was real fire. So they placed grass and leaves upon it, and tried to warm themselves at it, and one of them fanned the firefly with his breath.

A bird named Sūcīmukha, when he saw it, said to him:

“This is not fire, this is a firefly; do not fatigue yourself.”

Though the monkey heard that, he did not desist, and thereupon the bird came down from the tree, and earnestly dissuaded him, at which the ape was annoyed, and throwing a stone at Sūcīmukha, crushed him.[22]

84. Story of the Bull abandoned in the Forest

“So one ought not to admonish him who will not act on good advice. Why then should I speak? You well know that you brought about this quarrel with a mischievous object, and that which is done with evil intentions cannot turn out well.

84i. Dharmabuddhi and Duṣṭabuddhi [23]

For instance, there were long ago in a certain village two brothers, the sons of a merchant, Dharmabuddhi and Duṣṭabuddhi by name. They left their father’s house and went to another country to get wealth, and with great difficulty acquired two thousand gold dīnārs. And with them they returned to their own city. And they buried those dīnārs at the foot of a tree, with the exception of one hundred, which they divided between them in equal parts, and so they lived in their father's house.

But one day Duṣṭabuddhi went by himself and dug up of lus own accord those dīnārs which were buried at the foot of the tree, for he was vicious and extravagant.[24] And after one month only had passed, he said to Dharmabuddhi:

“Come, my elder brother, let us divide those dinars; I have expenses.”

When Dharmabuddhi heard that, he consented, and went and dug with him where he had deposited the dīnārs. And when they did not find any dīnārs in the place where they had buried them, the treacherous Duṣṭabuddhi said to Dharmabuddhi:

“You have taken away the dīnārs, so give me my half.”

But Dharmabuddhi answered:

“I have not taken them; you must have taken them.”

So a quarrel arose, and Duṣṭabuddhi hit Dharmabuddhi on the head with a stone, and dragged him into the king’s court. There they both stated their case, and as the king’s officers could not decide it, they were proceeding to detain them both for the trial by ordeal.

Then Duṣṭabuddhi said to the king's officers:

“The tree at the foot of which these dīnārs were placed will depose, as a witness, that they were taken away by this Dharmabuddhi.”

And they were exceedingly astonished, but said:

“Well, we will ask it to-morrow.”

Then they let both Dharmabuddhi and Duṣṭabuddhi go, after they had given bail, and they went separately to their house.

But Duṣṭabuddhi told the whole matter to his father, and secretly giving him the money, said:

“Hide in the trunk of the tree and be my witness.”

His father consented, so he took him and placed him at night in the capacious trunk of the tree, and returned home. And in the morning those two brothers went with the king’s officers, and asked the tree who took away those dīnārs.

And their father, who was hidden in the trunk of the tree, replied in a loud clear voice:

“Dharmabuddhi took away the dinars.”

When the king’s officers heard this surprising utterance, they said:

So they introduced smoke into the trunk of the tree, which fumigated the father of Duṣṭabuddhi so, that he fell out of the trunk on to the ground, and died. When the king’s officers saw this, they understood the whole matter, and they compelled Duṣṭabuddhi to give up the dīnārs to Dharmabuddhi. And so they cut off the hands and cut out the tongue[25] of Duṣṭabuddhi, and banished him, and they honoured Dharmabuddhi as a man who deserved his name.[26]

84. Story of the Bull abandoned in the Forest

“So you see that a deed done with an unrighteous mind is sure to bring calamity, therefore one should do it with a righteous mind, as the crane did to the snake.

84j. The Crane, the Snake and the Mungoose [27]

Once on a time a snake came and ate the nestlings of a certain crane as fast as they were born. That grieved the crane. So, by the advice of a crab, he went and strewed pieces of fish from the dwelling of a mungoose as far as the hole of the snake, and the mungoose came out, and following up the pieces of fish, eating as it went on, was led to the hole of the snake, which it saw and entered, and killed him and his offspring.

84. Story of the Bull abandoned in the Forest

“So by a device one can succeed. Now hear another story.

84k. The Mice that ate an Iron Balance [28]

Once on a time there was a merchant’s son, who had spent all his father’s wealth, and had only an iron balance left to him. Now the balance was made of a thousand palas of iron; and depositing it in the care of a certain merchant, he went to another land.

And when, on his return, he came to that merchant to demand back his balance, the merchant said to him:

“It has been eaten by mice.”

He repeated:

“It is quite true; the iron of which it was composed was particularly sweet, and so the mice ate it.”

This he said with an outward show of sorrow, laughing in his heart.

Then the merchant’s son asked him to give him some food, and he, being in a good temper, consented to give him some. Then the merchant’s son went to bathe, taking with him the son of that merchant, who was a mere child, and whom he persuaded to come with him by giving him a dish of āmalakas. And after he had bathed, the wise merchant’s son deposited that boy in the house of a friend, and returned alone to the house of that merchant.

And the merchant said to him:

“Where is that son of mine?”

He replied:

“A kite swooped down from the air and carried him off.”

The merchant in a rage said:

“You have concealed my son.”

And so he took him into the king’s judgment-hall; and there the merchant’s son made the same statement.

The officers of the court said:

“This is impossible; how could a kite carry off a boy?”

But the merchant’s son answered:

“In a country where a large balance of iron was eaten by mice, a kite might carry off an elephant, much more a boy.”[29]

When the officers heard that, they asked about it, out of curiosity, and made the merchant restore the balance to the owner, and he, for his part, restored the merchant’s child.

84. Story of the Bull abandoned in the Forest

“Thus, you see, persons of eminent ability attain their ends by an artifice. But you, by your reckless impetuosity, have brought our master into danger.”

When Damanaka heard this from Karaṭaka, he laughed and said:

“Do not talk like this! What chance is there of a lion’s not being victorious in a fight with a bull? There is a considerable difference between a lion, whose body is adorned with numerous scars of wounds from the tusks of infuriated elephants, and a tame ox, whose body has been pricked by the goad.”

While the jackals were carrying on this discussion, the lion killed the bull Sañjīvaka. When he was slain, Damanaka recovered his position of minister without a rival, and remained for a long time about the person of the king of beasts in perfect happiness.[30]

[M] (main story line continued) Naravāhanadatta much enjoyed hearing from his prime minister Gomukha this wonderful story, which was full of statecraft, and characterised by consummate ability.

[Additional note: on the “impossibilities” motif]

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

See Benfey, Pantschatantra, Leipzig, 1859, vol. i, p. 100; and J. Hertel, Tantrākhyāyika, Leipzig, 1909, part i, p. 128; part ii, p. 4 et seq. —N.M.P.

[2]:

Weber supposes that the Indians borrowed all the fables representing the jackal as a wise animal, as he is not particularly cunning. He thinks that they took the Western stories about the fox, and substituted for that animal the jackal. Benfey argues that this does not prove that these fables are not of Indian origin. German stories represent the lion as king of beasts, though it is not a German animal. (Benfey, op. cil., vol. i, pp. 102, 103.) See also De Gubematis, Zoological Mythology, p. 122.——Cf. Nights (Burton, vol. ix, p. 48n1). —n.m.p.

[3]:

See Benfey, op. cit., vol. i, p. 105 et seq., and vol. ii, p. 9. He considers a fable of Æsop, in which an ape tries to fish and is nearly drowned, an imitation of this. Cf. the trick which the fox played the bear in “Reineke Fuchs” (Simrock's Die Deutschen Volksbücher, vol. i, p. 148.)——See also Hertel, op. cit., part i, pp. 128, 129, and part ii, p. 7.— n.m.p.

[4]:

Cf. Benfey, op. cit., vol. ii, p. 21. In the first volume (p. 132 et seq.) he tells us that in the old Greek version of the fables of Bidpai, the fox, who represents the jackal, loses through fear his appetite for other food, and for a hen in the Anvār-i-Suhailī, 99. The fable is also found in Livre des Lumières, p. 72; Cabinet des Fées, p. xvii, 183, and other collections. The Arabic version, and those derived from it, leave out the point of the drum being found on a battle-field. Cf. also Campbell’s Tales from the West Highlands, p. 268:

“A fox being hungry one day found a bagpipe, and proceeded to eat the bag, which is generally made of hide. There was still a remnant of breath in the bag, and when the fox bit it, the drone gave a groan, when the fox, surprised, but not frightened, said: ‘Here is meat and music.’”

——See also Hertel, op. cit., part i, p. 129, and part ii, pp. 14, 15.—n.m.p.

[5]:

I follow the reading of the Sanskrit College MS.: mūḍhabuddhiḥ prabhur nyāyam ukṣṇānenādya śikṣyate. This satisfies the metre, which Brockhaus’ reading does not.

[6]:

This word generally means “crocodile.” But in the Hitopadeśa the creature that kills the crane is a crab.

[7]:

Here Somadeva omits four sub-tales: “The Monk and the Swindler”; “The Rams and the Jackal”; “The Cuckold Weaver and the Bawd”; and “The Crows and the Serpent.” They are given on pp. 223-227 of this volume. —n.m.p.

[8]:

See Benfey, op. cit., vol. i, p. 174 et seq., and vol. ii, p. 58 et seq. Cf. also Hertel, op. cit., part i, p. 131; part ii, pp. 22, 23. Only the versions of Kṣemendra and those in the Southern Pañcatantra and the Hitopadeśa resemble Somadeva’s ending. In all other versions the makara (nearly always taken to mean a crab) kills the crane before all the fish are devoured and returns to tell them of their enemy’s destruction. An oral tale derived from these versions appears in Ramaswami Raju’s Indian Fables, p. 88. Two other versions differ further. In Jātaka No. 38, and Dubois’ Pantcha-Tantra, p. 76, the crane (or heron) makes the fish leave the pond by prophesying a drought, and not by pretending that fishermen are coming with nets. For oral tales derived from these see G. R. Subramiah Pantulu, Folklore of the Telugus (3rd edit.), p. 47, also Indian Antiquary, vol. xxvi, 1897, p. 168; Steele, Kusa Jātakaya, p. 251; Parker, Village Folk-Tales of Ceylon, vol. i, p. 342 (three variants); W. W. Skeat, Fables and Folk-Tales from an Eastern Forest, p. 18. For further details see W. N. Brown, Journ. Amer. Orient. Soc., vol. xxxix, 1919, pp. 22-24.— n.m.p.

[9]:

Here he is called a jhaṣa, which means “large fish.”

[10]:

See the references given in Benfey, op. cit., vol. i, p. 179 et seq.; and Hertel, op. cit., pt. i, p. 131, and pt. ii, pp. 24, 25. Variants of this tale have found their way into a number of collections of oral tales. See Rouse, Talking Thrush, p. 130; Frere, Old Deccan Days, pp. 157-159; Pantulu, op. cit., p. 9. and Ind. Ant., vol. xxvi, p. 27; Butterworth, Zigzag Journeys in India, p. 16; Swynnerton, Romantic Tales from the Pañjāb..., p. 154; Ramaswami Raju, op. cit., p. 82; O’Connor, Folk-Tales from Tibet, p. 51; Parker, op. cit., vol. ii, p. 385; Skeat, op. cit., p. 28; Steel and Temple, “Folklore in the Pañjāb,” Ind. Ant., vol. xii, 1883, p. 177; and Dames, “Balochi Tales,” Folk-Lore, vol. iii, p. 517. All the above have been duly chronicled by W. N. Brown, op. cit., pp. 24-28. —n.m.p.

[11]:

Dr Kern conjectures abhigarjinam, but the Sanskrit College MS. reads malvā latrātigarjitam iti siṃham: “thinking that he was outroared there”; however, the word siinham must be changed if this reading is to be adopted. This-is the thirtieth story in my copy of the Śukasaptati.

[12]:

I prefer the reading kas of the Sanskrit College MS., and would render: “Whom can the king make his equal? Fortune does not proceed in that way.”——But D. has yas, as translated above.—n.m.p.

[13]:

I read doṣam for doṣo with the Sanskrit College MS.

[14]:

See Benfey, op. cit., vol. i, pp. 122, 123, and vol. ii, p. 71; and Hertel, op. cit., pt. i, p. 131, and pt. ii, pp. 29, 30; and cf. Parker, op. cit., vol. iii, p. 30, which closely follows the Textus Simplicior, i, 9.—n.m.p.

[15]:

See Benfey, op. cit., vol. i, pp. 230, 231, and vol. ii, p. 80; Hertel, op. cit., pt. i, p. 132, and pt. ii, p. 37 et seq.

[16]:

I adopted this translation of deśajña in deference to the opinion of a good native scholar, but might not the word mean simply “knowingcountries”? The crow then would be a kind of feathered Ulysses. Cf. Waldau’s Böhmische Märchen, p. 255. The fable may remind some readers of the following lines in Spenser’s Mother Hubberd’s Tale:—

“He shortly met the Tygre and the Bore

That with the simple Camell raged sore

In bitter words, seeking to take occasion

Upon his fleshly corpse to make invasion.”

[17]:

See Benfey, op. cit., vol. i, p. 231.

[18]:

See ibid., p. 235 et seq.; A. Manwaring, Marathi Proverbs, Oxford, 1899, No. 297, p. 41; Hertel, op. cit., pt. i, pp. 132, 133, and pt. ii, p. 40, and Das Pañcatantra, Leipzig, 1914, p. 277. Ṭiṭṭibha is nearly always translated as “strandbird.”— n.m.p.

[19]:

See ibid., p. 239 et seq. The original source is probably the Kacchapa Jātaka. See Rhys Davids’ Introduction to his Buddhist Birth Stories, p. viii. In Coelho’s Contos Populares Portuguezes, p. 15, the heron, which is carrying the fox, persuades it to let go, in order that she may spit on her hand. [A similar incident appears on p. 170 of this volume.] Gosson in his Schoole of Abuse, Arber’s Reprints, p. 43, observes:

“Geese are foolish birds, yet, when they fly over Mount Taurus, they show great wisdom in their own defence, for they stop their pipes full of gravel to avoid gaggling, and so by silence escape the eagles.”

——Cf. Hertel, op. cit., pt. i, p. 133, and pt. ii, pp. 40, 41. In Dubois' Pantcha-Tantra, p. 109, it is a fox who attracts the attention of the tortoise and so causes him to fall. Two oral tales are founded on this version—viz. Pieris, “Siṃhalese Folklore,” Orientalist, vol. i, p. 134; and Parker, op. cit., vol. i, p. 234.— n.m.p.

[20]:

I.e. “the provider for the future,” “the fish that possessed presence of mind,” and “the fatalist who believed in kismet.”——Cf. Hertel, op. cit., pt. i, p. 133, and pt. ii, p. 41 et seq. Edgerton (Pañcatantra Reconstructed, vol. ii, p. 314) translates as “Forethought,” “Ready-wit,” and “Come-what-will.” See Pantulu, op. cit., p. 53, and Ind. Ant., vol. xxvi, p. 224.—n.m.p.

[21]:

See Benfey, op. cit., vol. i, pp. 269, 270. In the Greek version Symeon Seth substitutes for the firefly λίθον στίλβοντα, while in the Turkish version, in the Cabinet des Fées, we read of “Un morceau de crystal qui brillait.”—— It would, however, be more correct not to translate “firefly” with Tawney, but “glow-worm” with Benfey, Hertel and Edgerton. There has always been a certain amount of confusion between “firefly” and “glow-worm,” owing chiefly to the fact that both terms are used indiscriminately. Correctly speaking, “firefly” is the term popularly used for the American click-beetle (Pyrophorus) and is entirely confined to tropical America. It is interesting to note that American Indians of these latitudes sometimes keep “fireflies” in little cages for illumination at night. They are also used for personal adornment. The “glow-worm,” on the other hand, is the Iximpyris noctiluca, a wingless female beetle common throughout Europe and the East, some specimens of which can fly; hence these have also been called “fireflies.”—N.M.P.

[22]:

See Crooke, op. cit., vol. ii, p. 257.— n.m.p.

[23]:

See Benfey, op. cit., vol. i, p. 275 et seq., where differences in the various recensions are detailed. The story was also found in Tibet by Babu Śarat Candra Dās, headmaster of the Bhūtia school, Darjiling.—— Cf. Hertel, op. cit., pt. i, p. 134, and pt. ii, p. 51 et seq.; Pantulu, op. cit., p. 17, and Ind. Ant., vol. xxvi, p. 55; and K. N. Fleeson, Laos Folklore of Farther India, p. 108. See also F. Edgerton, “Evil-Wit, No-Wit and Honest-Wit,” Journ. Amer. Orient. Soc., xl, 1920, p. 271.—n.m.p.

[24]:

I read with the Sanskrit College MS. [and D, text] asadvyayī.

[25]:

A well-known punishment for thieves. See Bloomfield, “Art of Stealing,” Amer. Journ. Phil., vol. xliv, p. 227.—n.m.p.

[26]:

I.e. “Virtuously-minded.” His brother’s name means “evil-minded.”

[27]:

Benfey (op. cit., vol. i, pp. 167-170) appears not to be aware that this story is in Somadeva. It corresponds to the sixth in his first book, vol. ii, p. 57 et seq. Cf. Phædrus, i, 28; and Aristophanes, Aves, 652.——See also Hertel, op. cit., pt. i, p. 134, and pt. ii, p. 53 ; and Steele, Kusa Jātakaya, p. 255.—n.m.p.

[28]:

See the note at the end of this chapter.— n.m.p.

[29]:

The argument reminds one of that in “Die kluge Bauerntochter" (Grimm’s Märchen, 94). The king adjudges a foal to the proprietor of some oxen because it was found with his beasts. The real owner fishes in the road with a net. The king demands an explanation. He says:

“It is just as easy for me to catch fish on dry land as for two oxen to produce a foal.”

See also “Das Märchen vom sprechenden Bauche,” Kaden, Unter den Olivenbäumen, pp. 83, 84.

[30]:

For literary analogues see Sandhibheda Jātaka, No. 349 (Cambridge edition, vol. iii, pp. 99); Schiefner and Ralston’s Tibetan Tales, p. 325; B. Jülg, Mongolische Märchen, p. 172; Busk, Sagas from the Far East, p. 192; Chavannes, Cinq Contes et Apologues, ii, p. 425. For oral versions see Parker, Village Folk-Tales of Ceylon, vol. iii, p. 22; and W. W. Skeat, Folk-Tales from an Eastern Forest, p. 30. For further details see W. N. Brown, Journ. Amer. Orient. Soc., vol. xxxix, 1919, pp. 18, 19, to whom I am indebted for the above references and many of those in notes to other tales in Book I of the Pañcatantra.—n.m.p.