The civilization of Babylonia and Assyria

Its remains, language, history, religion, commerce, law, art, and literature

by Morris Jastrow | 1915 | 168,585 words

This work attempts to present a study of the unprecedented civilizations that flourished in the Tigris-Euphrates Valley many thousands of years ago. Spreading northward into present-day Turkey and Iran, the land known by the Greeks as Mesopotamia flourished until just before the Christian era....

Part XIII

A subdivision of the Babylonian-Assyrian art in which unusual skill was developed at an early period and which reached an even higher degree of perfection in Assyria was the work in metals notably copper and bronze but also silver. Abundant evidence has been found that the Euphrates Valley had its stone age which no doubt overlapped as elsewhere into the age of metals. As early as the third millennium we find specimens of engraving on copper blades, and of copper and bronze statuettes and other votive objects that testify to the high antiquity of the metallurgical art.

Despite its bad state of preservation, there is much to admire in the figure of a lion engraved on the tang of a copper blade, found at Telloh and which, measuring about 31 1/2 inches in length, belonged to a lance which, as the partially effaced inscription shows, was dedicated by a "king of Kish " to some deity. [1]

The head of the lion is well drawn and, but for the conventionalized shape of the mane, the general effect is pleasing. Another object of copper, [2] belonging perhaps to a still earlier period, shows a lion in a crouching position attached to a spike.

While the shape of the head betrays a certain crudeness, and the body is somewhat foreshortened, yet there is much life in the effect as a whole, due to the admirable manner in which the legs are portrayed, conveying the impression of an animal about to leap at some prey. Passing by some representations of animals moulded out of copper but so covered with oxidization as to be not clearly distinguishable, a fair idea of the traits of this art may be obtained from a series of votive statuettes, showing male and female figures carrying baskets on their heads, kneeling gods, female figures and animals in various poses.

The basket bearers are of two types, one in which only the upper part of the body is shown, while the other portion, suggesting a skirt reaching to the feet, is taken up with a dedicatory inscription, the other in which the whole body is shown, the upper part and the legs being nude, while a short skirt hangs down from the waist, affording space for the inscription of the ruler who offers the statuette as a votive gift. The most striking feature of these figures is the graceful attitude of the hands in balancing the basket on the head ; the least satisfactory is the blank expression on the face, and this despite the fact that the simple features are drawn in good proportion.

In contrast to the awkward position of the feet on the sculptures in soft or hard stone, the pose is perfectly natural here. The figure stands firm and yet easy. There is also well expressed in the dignified attitude of the statues as a whole the devotion to a deity, symbolized, as in the case of the Ur-Nina plaques [3] by the workman's basket indicative of a direct participation in the erection of a sacred edifice.

Belonging to a period not far removed from that of Gudea we have several specimens of votive objects, consisting of a cone to be fastened to some part of a temple or sanctuary and to which the figure of a kneeling god is attached — rather awkwardly to be sure.

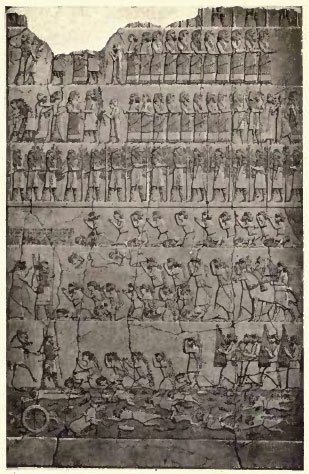

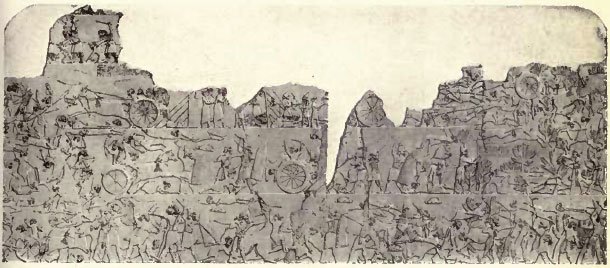

PLATE LXI

Fig. 1, Assyrian army and captives

Fig. 2, Battle scene. Conflict between Assyria and Elam

Fig. 1, King AShurbanapal of Assyria (668-626 B.C.) with his Queen

The figures themselves, however, are exceedingly well executed. The body is well moulded, the features are clean cut, there is a vigorous expression in the eye, the nose is powerful and the mouth firm. The head is slightly out of proportion to the body, though not to such a degree as in the case of the statue of Gudea. We thus get the impression of a somewhat thick-set figure, which, however, is partly due to the fact that the Sumerians were a people of short build ; they, therefore, pictured their gods in the same general style, though this did not hinder them from representing them as much taller than themselves, just as the kings were drawn as larger than the common folk (see Plate LXIII).

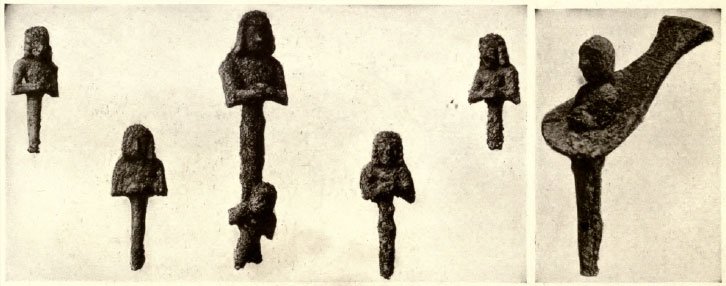

Much cruder are a series of votive statuettes, serving as amulets and stuck apparently into the walls as a protection against the encroachment of evil demons. They all have heads of females, but only the upper part of the body is clearly indicated. The clasped hands are poorly executed, the faces somewhat more carefully modelled, while the hair hanging about the neck has the appearance of a wig (Plate LXIV, Fig. 1) .

The grotesqueness is accentuated in some of the statuettes which are provided with a large flat ring shaped like a bird's tail, into which they were slipped to aid in bearing the burden of a tablet of stone attached to the heads (Plate LXIV, Fig. 2), and bearing a dedicatory inscription. In some cases, however, these tablets were bored with holes into which the heads of the statuettes were inserted. Such statuettes were found in groups, buried in hollows and walled in with bricks and bitumen.

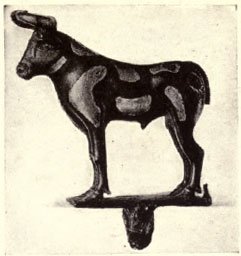

Perhaps the fact that they were to be kept out of view accounts for the little care bestowed on their execution. Eising again to a high degree of workmanship are heads and bodies of animals belonging likewise to a very early period. A crouching bull on the top of a nail provided with a point to be stuck into a wall is an admirable piece of work, the head being well modelled, the body in proportion and the pose natural (Plate LXIII). Equally good is a bronze bull standing on a flat support, though the artistic effect is spoiled somewhat by the bits of silver inlaid across the body to represent the variegated coloring of the skin.

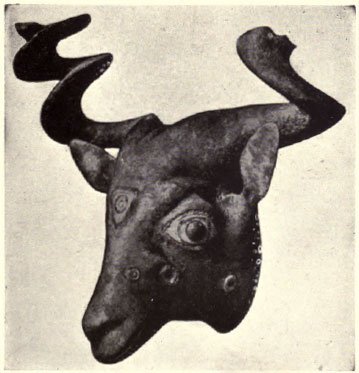

The head with the gracefully shaped horns is particularly well done. Still finer are two animal heads hollowed out of copper, one a bull's head found at Telloh, the other that of a Markhur goat with elaborately crumpled horns. The eyes in the one head are inlaid with mother of pearl, while the pupils are of lapis lazuli ; in the other case, the eyes are made of shell, the pupils being colored dark brown (Plate LXV) .

The extensive use to which copper was put in Babylonia is shown by the very large number and variety of art objects and utensils found in the excavations at various sites. Most of these utensils being made for purely practical purposes, such as daggers, hatchets, knives, fish hooks, spear-heads, and vases and dishes of various kinds, have no artistic value, while others that may have had were found in such a bad state of preservation as to render them uncertain witnesses.

Moulds of clay for metal casting appear to revert to a very early age, and most of the smaller copper objects found were prepared in this way. Earrings and jewelry of various kinds were also made in the same way, as well as bronze objects, which belong to a later period after the discovery of making bronze by adding an alloy of tin had been made. The use of bronze becomes more common as we pass down the ages until in the best Assyrian period it gradually supplants copper.

PLATE LXIII

Fig. 1, Votive offerings (copper) from Telloh

PLATE LXIV

Fig. 1 (left), Votive statuettes (copper)

Fig. 2 (right), Copper statuette with flat ring attachment

PLATE LXV

Fig. 1, Bronze Bull

Fig. 2, Goat with crumpled horns (copper)

Belonging probably to the later Babylonian period, is a remarkable bronze plaque, detailing a ceremony of exorcism of a demon of disease. The interesting feature of this plaque from the artistic point of view is the grouping of the figures in the second and third rows.

In the upper row we have a series of nine symbols of the chief gods of the pantheon, the crescent standing for Sin, the moon god, the eight-rayed star for the goddess Ishtar, the stylus to the left of the star for Nabu, the god of writing and wisdom, the adjoining spear for Marduk, the head of the pantheon, and so on through the list.

In the second row is a group of seven demons, frequently referred to in the incantation formulas against the demons of disease, and who are regarded as responsible for the bodily ills to which human flesh is heir.

The third row pictures the ceremonies for driving the demons of disease out of the victim who lies on a couch with uplifted hands. At either end of the couch stands an exorcising priest, dressed in a fish skin to symbolize that he is acting for Ea, the god of waters, and of whom the fish would be a natural symbol. The two deities chiefly invoked in incantation rituals [4] are Ea as the god of the watery element, and Nusku (or an equivalent) as the god of fire, water and fire being looked upon as the two chief purifying elements to purge the sufferer from disease which was conceived as a kind of impurity.

These exorcising priests are performing some ceremony to symbolize the cleansing of the victim. At the left end is an altar with food which typifies the sacrifice offered by the sufferer as part of the ceremony. To the right of one of the priests the demons are pictured as being driven off.

In the lowest compartment, the central figure is a representation of the demon Labartu, holding a serpent in each hand, and with pigs sucking at her breasts. She kneels on an ass, and is apparently being driven off in a boat by the demon to her left, who brandishes a weapon or whip in his uplifted hand. The various specimens of food to the right of Labartu may again represent offerings made to the demons to induce them to release their hold, or to the gods appealed to for their aid. The water below Labartu is represented by swimming fishes and the shore by two trees at the right end.

The plaque thus tells the whole story of the ceremony in a most realistic manner. The symbolism, it will be noted, dominates the scenes portrayed to such an extent that, if it were intelligible to us in all its minutest details, we would have a complete picture of the incantation rites and of the ideas underlying each incident in these rites (Plate LXVI).

The use of copper in Babylonia either pure or with an alloy which converted it into bronze was very extensive, indeed, as is shown by the large variety of objects, mirrors, daggers, spear heads, dishes, cauldrons, weights, etc., found in the mounds. Of the bronze objects found in Babylonia a bell, now in the Berlin Museum, merits to be singled out because of the unusually delicate design running around the cup, and which again represents demons portrayed as wild animals of hybrid character, in an upright posture and in a threatening attitude.

Five of them have the heads of hyenas, but have human hands and apparently also human bodies ; they are clothed in short skirts, and the grotesqueness is increased by the tails and clawed feet ; the sixth has a human shape, while in the midst of these demons is again the exorcist, clothed in fish scales to symbolize him as the priest of the water god Ea with whose aid the demons are being driven away.

The symbolism is extended to the handles of the bell which are in the form of serpents, and to the turtles and to another design the exact nature of which escapes us. Presumably these designs are emblems of the gods like those on the boundary stones, [5] added as further protection against the mischievous workings of the evil demons (Plate LXVII).

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Decouvertes en Chaldee, PI. 5 ter, No. 1 ; see also ib., PL 6 ter No. 2.

[2]:

Found at Bismya (see Banks, Bismya, p. 237). Banks speaks of the object as bronze, but it is probably copper, as Handcock, Mesopotamia*, Archaeology, p. 251, suggests, with an accidental alloy.

[3]:

Above, Plate XL VI, Fig. 1.

[4]:

Above p. 246 seq.

[5]:

See below p. 416 seq.