The civilization of Babylonia and Assyria

Its remains, language, history, religion, commerce, law, art, and literature

by Morris Jastrow | 1915 | 168,585 words

This work attempts to present a study of the unprecedented civilizations that flourished in the Tigris-Euphrates Valley many thousands of years ago. Spreading northward into present-day Turkey and Iran, the land known by the Greeks as Mesopotamia flourished until just before the Christian era....

Part XI

It is time now to turn to Assyrian sculpture, which, while showing its dependence upon that of Babylonia, nevertheless strikes out in new directions and shows traits of a decidedly original character. In the choice of subjects Assyrian art reflects the ambitions of the rulers and the martial spirit of the people. Our material is not sufficient to enable us to follow the development of Assyrian sculpture through its various phases.

We cannot carry it further back at present than the twelfth century, and the specimens up to the middle of the ninth century are so few that we must for the present begin the survey from the comparatively late period when Assyria was already approaching the zenith of her power. It seems, however, safe to assert that the general traits of Assyrian sculpture are already fixed several centuries before Ashurnasirpal III. (883-859 B.C.).

The dependency upon Babylonian prototypes is seen in the portrayal of the human figure, which remains throughout the entire period stiff, lifeless and extremely" conventionalized. On the other hand, there is considerable advance in showing soldiers and huntsmen in action, though here too conventionalism lays shackles on the freer development of the art, but the most striking contrast to the bas-relief sculptures of Babylonia is the breaking away from symbolism in the case of Assyrian art to become purely and completely realistic.

The result is a decided advance in the direction of giving more life to the scenes depicted; they come closer to reality. The marching soldiers, being no longer chosen to symbolize the kind that marched to an attack, move with greater ease. The attack is effectively pictured in a continuous series of designs, each representing some striking moment in the battle, whether real or due to the fancy of the artist is of little moment. Even if the scene is based on a real occurrence, the execution is fanciful a circumstance which affords a larger and freer scope to the artist's imagination, so essential to the development of a true art.

The palace walls of Ashurnasirpal were covered with bas-reliefs illustrative of incidents in the campaigns of the king, and picturing his activity in the chase, which was the favorite sport of the rulers.

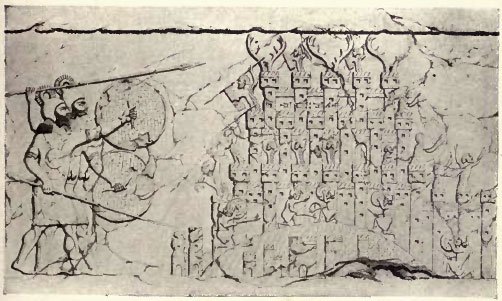

PLATE LIV

Fig. 1, Hittite Sphinxes, showing influence of Assyrian art

Fig. 2, Assyrian army, attacking a fort

A few specimens of each will suffice to show the remarkable vigor displayed in portraying armies in action, as, for example, in attacking a city by means of a battering ram, reinforced by archers, who come into a hand-to-hand encounter with the enemy. The attention to details is also noticeable in the trappings of the horses and in the military equipment of rulers, of the high officers and of the common soldiers. The grouping of the figures is also carried out with taste and skill, though occasionally the scenes are too crowded, and the impression is blurred through the endeavor of the artist to show too much.

A defect of the art at this period which is particularly noticeable in the hunting scenes is the stiffness and awkwardness in the drawing of the animals, so much inferior in this respect to the representation of the human figure. While the charioteer who drives the horses with the king at his side, discharging the arrows at the approaching lion, admirably displays the strain on the muscles of the arm and the tension in the face as he tries to control the dashing steeds, the horses themselves seem to be suspended in the air.

The artist fails to convey the impression that the horses are speeding along, despite the posture of the forelegs, evidently intended to suggest a rapid dash. There is, indeed, a certain degree of force in the faces of the horses, but a comparison between a number of the bas-reliefs reveals that this expression is stereotyped and falls therefore under the ban of conventionalism. The limitations of the art are even more apparent when it comes to the portrayal of the lions in pursuit, or wounded by the arrows shot at them.

The artist succeeds in his attempt to convey the impression of the pain and terror endured by the hunted animal, but the convulsions of the body are drawn in so awkward a manner as to border on the grotesque. We shall note as we proceed to later generations the progress made in this respect until at the highest point of its development, the Assyrian art is remarkably successful also in the naturalness and variety of the poses given to lions, wild horses and other animals when pursued or wounded by the royal sportsmen (see Plate VIII).

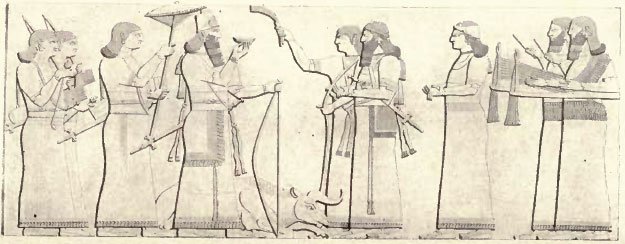

The best specimens of the art in the early period are those in which the king is portrayed surrounded by his attendants or officers. These are marked by the most scrupulous attention to details, as, for example, in the scene where the king is portrayed with the bow in one hand and a bowl in the other containing a libation to be offered to the deity after the chase. The embroidery, borders and tassels of the royal garment are executed with the greatest possible care.

Not a detail is overlooked, down to the embroidery on the edge of the short sleeves. Necklace, bracelets and earrings as well as sandals are similarly worked out in detail, while both in the case of the king and of the eunuch with the fly-flap standing before him, almost every strand of the abundant hair can be distinguished.

The endeavor is also made to indicate the strong muscles of the arm, though owing to the substance a rather hard limestone this feature can hardly be termed an artistic success. The pose of the figures is easy and dignified, that of the king effectively conveying the impression also of royal majesty (see Plate LV).

The palace at Khorsabad [1] of Sargon, who ruled from 721-706 B.C., and the founder of the dynasty which gave to Assyria its most famous rulers, has yielded a large number of specimens of sculptured bas-reliefs which enable us to trace the beginnings of the art which manifests itself chiefly in the growing complexity of the designs. The artists of each succeeding age evidently vied with their predecessors in the endeavor to vary the monotony of the two main subjects chosen for illustration war and sport by the greatest possible diversity in the details.

PLATE LV

Fig. 1, King Ashurnasirpal III of Assyria. (883-859 B.C.), hunting Lions

Fig. 2, King Ashurnasirpal III, pouring libation over wild bull.

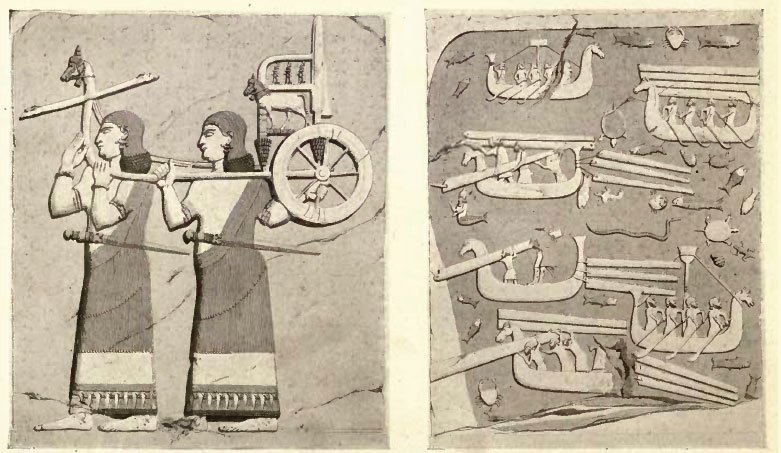

PLATE LVI

Fig. 1 (left), Attendants carrying throne (Khorsabad)

Fig. 2 (right), Transporting wood across a stream (Khorsabad)

To accomplish this, the scale of representation was magnified, and each episode of the campaign or the chase selected correspondingly amplified by introducing as many figures as possible, and all in action.

There is, however, the same stiff conventionalism in the beardless figures carrying portions of the royal throne. Not only are the faces devoid of expression, but there is a total lack of any indication of muscular action. In contrast to these defects, great care is bestowed on the dress and on such details as the trappings of the horses and the carving of the ornaments of the throne (see Plate LVI, Fig. 1).

An attempt at introducing variety into what might otherwise be monotonous representations is to be seen in the portrayal of Assyrian workmen, transporting wood across a stream. The large variety of marine life is portrayed in a most vivid manner, and likewise the action of the sailors rowing the ships or loading or unloading large bars of wood which, it will be observed in some cases, are placed on a deck above the heads of the rowers, and in others are attached to the stern of the boat (see Plate LVI, Fig. 2).

The limits put upon the art through the extreme conventionalism is shown in the representation of attacks upon forts, such as the one here given, which despite its mutilated character is sufficiently well preserved to give the characteristics of the art of the period. Note the similarity of posture in the case of those appearing at the openings of the various parts of the fort, and the stiff and naive method of representing the variour stories of the fort and the lack of perspective (Plate LIV, Fig. 2). Even more characteristic is the large figure of the Babylonian hero Gilgamesh represented in the act of strangling a lion, which evidently formed one of the achievements of the hero. The beard is drawn in the usual conventionalized style, but there is an expression of great power in the face, due, to be sure, more to the exaggeration of the features than to artistic delicacy.

The expression on the lion's face is ludicrous, and the unequal proportion between the gigantic hero, and the diminutive lion is an indication also of the lack of humor on the part of the Assyrian artist, who did not recognize that it would have been more to the credit of the hero to strangle a really large lion than a little baby whelp (see Plate LVII).

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

See above Plate IV and V, and for further illustrations Botta et Flandin, Monument de Ninive, (Paris. 1849).