The civilization of Babylonia and Assyria

Its remains, language, history, religion, commerce, law, art, and literature

by Morris Jastrow | 1915 | 168,585 words

This work attempts to present a study of the unprecedented civilizations that flourished in the Tigris-Euphrates Valley many thousands of years ago. Spreading northward into present-day Turkey and Iran, the land known by the Greeks as Mesopotamia flourished until just before the Christian era....

Part XIV

An abundance of further details in all these and other aspects of social life is furnished by the many hundreds of business and legal documents that have been preserved from the period of the definite union of the Euphratean states under the rule of the Semitic kings of Babylon, the period of the so-called first dynasty of Babylon, extending from c. 2225-1926 B.C. [1]

In contrast to the business documents of the Agade, Ur and Isin dynasties which, as we have seen, are so largely taken up with mere accounts and lists connected with the temple organization in one centre or the other, those of the first dynasty of Babylon are of a much more miscellaneous character and for the most part taken up with transactions between laymen dealing with the ordinary business affairs and with more or less elaborate lawsuits brought by contending persons.

There is, to be sure, every reason to believe that such documents will also be found some day in abundance for earlier periods, but for the present we must depend upon the material dated in the reigns of the rulers of the first dynasty and of subsequent periods for a more definite picture of business activities among laymen and of the manner in which justice was carried out in the courts of the land. The business and legal documents of this period, moreover, are written in Semitic or Akkadian which makes the task of interpretation less precarious, for despite recent progress in the interpretation of Sumerian texts, there is much in such material that is still obscure.

When we reach Semitic texts, we are on firm soil. It is also a great advantage to have as a guide and control for the understanding of the business and legal documents of this period the code of Hammurapi of which we have for this reason given a rather full analysis. [2]

This great code became a standard for all times, though as has been noted additions continued to be made to it, and modifications were introduced to keep pace with changing conditions and to embody new decisions that were constantly being rendered, albeit on the basis of the principles on which the code was established.

Before giving some examples of business and legal documents of the period of Hammurapi, as we may also call the age of the first dynasty of Babylon from its most prominent representative, it will be well to outline the methods perfected in his days for the legal administration of the country. [3]

In the first place, we note by the side of the older and original tribunals in the temples, entirely in the hands of the priests, a class of civic judges or magistrates before whom legal documents could be drawn up and to whom litigants came to have decisions rendered.

Such magistrates acted in the name of the king, and it would appear that their functions were extended after the days of Hammurapi so that only specific cases requiring an oath in the presence of the gods were referred to the " judges of the temple," as the priestly officials in contra-distinction to the lay judges were commonly designated. The institution of civil courts marks a decided decline in the authority of the priests, though as a court of last instance the temple continued to maintain itself to the closing days of the Babylonian empire.

There are also traces of a kind of popular assembly with certain judicial functions, [4] and in addition, the governors of provinces and the chief magistrates of cities could be appealed to, to render justice. Furthermore, the prominence acquired by the city of Babylon as the capital of the country gave to the judges of Babylon a position not unlike that of a supreme court; and we have instances of cases, dealt with in Sippar and elsewhere, being referred to the tribunal of Babylon.

All this points to an elaborate system of administration, keeping pace with the union of the states of the Euphrates Valley under a central authority and to the growing complications of social life, necessitating the institution of lower and higher courts, and differentiating the functions of the many officials required to maintain law and order.

The large number of actual contracts of all kinds and legal cases embodied in the material at our disposal from the Hammurapi period also furnish us with an extensive legal terminology, as the result of many centuries of legal procedure. This procedure, furthermore, led to fixing a definite form for legal documents which all thus turn out to be arranged according to a definite sequence in the arrangement of the data. Inasmuch as the legal document involves, primarily, the disposition of some object real or personal estate or a slave, child, wife or some member of the household the person or object in question is first mentioned with such specifications as are needed to identify it, as, for example, the definite location of a house, field or orchard, and the description of the produce, article of merchandise, sum of money or individual in question.

After this come the parties concerned,

- seller and buyer, or

- the parties to any kind of an agreement, or

- the litigants,

- slave owner and slave (or slaves),

- father or mother and children, members of a household, and the like.

The business transaction itself is then specified loan, marriage agreement, sale or lease, gift, adoption, or claim is set forth as the third division, again with the necessary specifications, after which the formal decision reached is indicated, to which the parties involved agree in the case of the disposition of property by an oath to abide by the terms of the document and to renounce all further claims. The names of the witnesses and the date terminate the document.

The attachment of a seal or of seals [5] to legal documents was customary from the earliest period on, without, however, being obligatory.

In the case of deeds of sale, it is the seller who attaches his seal, in the case of a lease the lessee, in the case of a loan the creditor, in the case of a work contract the contractor, in the case of an inheritance deed, the one who disposes of the property, and the guarantor in case of a bond, in general, therefore, the one who gives up a claim, or who takes an obligation upon himself, while in cases where both parties take obligations upon themselves, both attach their seals.

So, for example, in marriage contracts, the two contracting parties seal the document; the same in the case of partnership agreements, or in deeds involving exchange or division of property, while in cases of adoption, the father and the foster parents, though at times the foster parents only. The custom varies somewhat in different centres and at different times.

So, for example, at Nippur the seal appears to have been made specifically for the document ; it is more in the nature of a formal attest than the signature of the one party or of the two parties, as is shown^by the fact that two names are combined on one seal, and the seal itself is in the form of a rectangular stamp made of a soft material and impressed on the clay like a die, and not a seal cylinder, made of some hard material and which is always that of an individual, rolled over the document. [6]

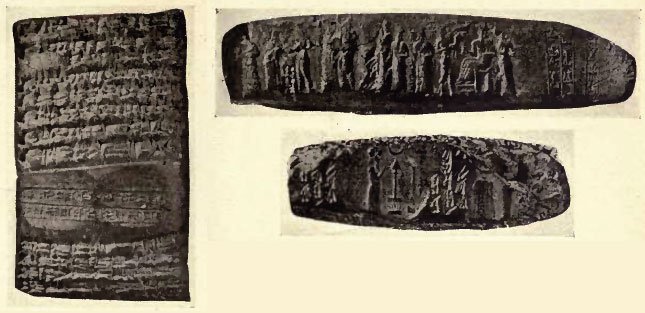

PLATE XXXVI

Fig. 1 (left), Legal tablet with seal

Figs. 2 and 3 (right), Seal impressions on legal and commercial tablets

Fig. 4, Nail-Marks on legal tablets as substitute for seal

In a general way it may be said, therefore, that the seal was a guarantee for the validity of the document on the part of the person or persons who yielded certain rights, or who took obligations on themselves, but in addition to this it also served as a protection against alterations or additions to a document by being rolled over the document wherever there was room for it, and frequently even directly over words of the document.

This feature of the seal is particularly apparent in cases where the original document was enclosed in a cover or envelope of clay, on which often a brief docket of the nature of the document was added with seals to prevent the cover from being detached with fraudulent intent.

In most cases, however, the envelope contains a duplicate of the document, the agreement of which with the inner one would furnish a guarantee for the authenticity of the original in case the question of genuineness were raised. The addition of such a duplicate was not obligatory, though it became sufficiently common to lead to the decision that the absence of a duplicate was no ground for questioning the validity of a legal document. [7]

In addition to these two purposes for which seals were attached, the witnesses or even parties not named as witnesses attached their seals as signatures which might be appealed to in cases of dispute as proof for the actual consummation of an agreement. In place of a seal we find in documents down to the Cassite period, the attachment of a bit of clothing imbedded in the clay document while still in a soft condition, and specifically referred to in the document as a substitute for the seal.

The technical term for such a guarantee imbedded in the document (as in the case of the seal) by the one who disposes of a right or claim, or by the one who takes an obligation upon himself is sissiktu (or sisitu) which appears to designate the fringe attached to a garment. [8]

Again, in place of the seal, the finger-nail marks of the contracting party or parties are scratched on the tablet in lieu of a seal. [9]

This may have happened originally in the case of persons who had no seal, but in time became quite a common attest to a legal document, of which the cross or mark, still recognized in modern times as a signature to legal documents, is a direct successor. The most solemn feature in connection with legal documents was the oath which was by no means obligatory in all agreements; it was restricted chiefly to cases where individuals through sale, exchange, or dissolution of partnership, or through a testament or deed of gift renounced certain claims and, as already pointed out, it is always the person who gives up further claims who swears the oath, as it is he who attaches his seal by way of further confirmation. [10]

We also find the oath where obligations are imposed on individuals, though limited, as it would appear, to marriage contracts, deeds of adoption, appointment of heirs and manumission of slaves all being transactions involving family and household affairs.

The oath is not taken in the case of loans, leases, labor contracts, commissions and the like. We have seen that in the earliest days the oath is taken in the name of the king, who in his capacity as the representative of the deity [11] has the quality of sanctity attached to him.

In the days of Hammurapi, the gods either take the place of the king or the name of the king is added to that of the gods, and frequently also the name of the city or temple in which the document is drawn up. The change points to the growing secularization of the royal office, leading to the substitution of the gods as a more solemn affirmation.

The oath was taken by the "raising" of the hand, [12] and the place where it was taken was naturally in the temple. Before the civil courts, sitting outside of the temple, no oath could be taken, and when it became necessary in a suit brought before such a tribunal to introduce the oath, the case was transferred to the "temple " judges.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

The definite determination of the chronology of this period we owe to the researches of F. X. Kugler, Sternkunde und Sterndienst in Babel (Miinster, 1910), ii, 1, pp. 234-311.

[2]:

Above pp. 283-315.

[3]:

For details see Edouard Cuq, "Essai sur 1'organisation judiciaire de la Chaldee a 1 'epoque de la premiere dynastic Babylonienne (Revue d 'Assyriologie VII, pp. 65-101).

[4]:

This assembly met at the "wall" of a city, and was accordingly known as the "wall of Sippar," "wall of Nippur," etc., according to the locality. Such an assembly may well have been a survival from primitive days when the "elders" constituted the tribunal before which litigants came antedating, therefore, the formal organization of courts of justice in the temples.

[5]:

See for further details regarding the seal cylinders which were rolled over or impressed on the documents, at the close of Chapter VII. pp. 418-426.

[6]:

See on this subject of the "Nippur" seals Poebel's discussion in Babylonian Legal and Business Documents from the first dynasty of Babylon (Phila., 1909), pp. 51-55.

[7]:

See Winckler, Die Gesetze Hammurabis (Leipzig, 1904), p. 86 (2,4-14).

[8]:

See on this term and the custom which it illustrates Ungnad in Orient. Litteraturzeitung, vol. ix, sp. 163; xii, sp. 479; and Clay, Babylonian Expedition, XIV, pp. 12-14. The Hebrew term sisit for the fringe to be attached to garments according to the Priestly Code (Num. 15, 38) is probably a loan word from the Babylonian.

[9]:

Specifically stated as such in the document.

[10]:

See on the oath in Babylonian and Assyrian inscriptions a monograph by S. A. B. Mercer, The Oath in Babylonian and Assyrian Literature (Paris, 1912), with supplementary articles in the Journal of the American Oriental Society, vols. 33 and 34, and in the American Journal of Semitic Languages, vol. 29, No. 2.

[11]:

Above, p. 288. The rulers of Agade and of Ur have the determinative of deity attached to their names. The divine descent of kings thus reverts to a very early period in the history of man.

[12]:

Prom the stem nashu, "to raise", a noun nishu was formed which acquired the technical force of "taking the oath". See Schorr, Altbabylonische Rechtsurkunden, p. xxxiii, note 1.