The civilization of Babylonia and Assyria

Its remains, language, history, religion, commerce, law, art, and literature

by Morris Jastrow | 1915 | 168,585 words

This work attempts to present a study of the unprecedented civilizations that flourished in the Tigris-Euphrates Valley many thousands of years ago. Spreading northward into present-day Turkey and Iran, the land known by the Greeks as Mesopotamia flourished until just before the Christian era....

Part VI

The great antiquity of Sippar is vouched for by the results of excavations conducted on the site, [1] but it is still an open question whether another seat of Shamash worship at Larsa is not even older. We must, at all events, assume some relationship between the two centres, for in both places the names given to the patron deity and to his temple, E-Babbar ("resplendent house"), are identical.

It is a direct consequence of the Semitic control of Babylonia which becomes pronounced in the days of Sargon and Naram-sin [2] that Shamash acquires his pre-eminent position as the sun-god par excellence, for Sippar is in close proximity to Agade and shared with the latter the prestige of being the capital of the kingdom that rose to supremacy under Sargon.

Shamash is represented on monuments and on numerous seal-cylinders [3] as a majestic figure seated on a throne, or stepping over a mountain, or passing through gates to symbolize the rise of the great orb of light, or sailing in a boat across the heavens. Frequently also rays are depicted as issuing from his shoulders. As the god of light, he is the general object of adoration, and the specific association with Larsa or Sippar does not stand in the way of his becoming a deity whose worship extends throughout Babylonia and passes northward into Assyria.

In all large centres temples or shrines to Shamash were erected. Babylonian and Assyrian rulers from the oldest to the latest period include Shamash in the invocations to the chief gods of the pantheon at the beginning of votive or historical inscriptions. So, to give an example of the early period, Lugalzaggizi, the king of Uruk (c. 2750 B.C.), designates himself in the introduction to one of his inscriptions [4] as

"The great patesi [5] of Enlil, endowed with understanding by Ea, [6] whose name was called [7] by Babbar (i.e., Shamash), the chief minister of Sin, [8] the lieutenant of Babbar, the provider for Innina, the child of Nisaba, [9] nourished with the milk of Ninkharsag, [10] the servant of Mes, [11] the priest of Uruk."

At the other end of Babylonian history we find the last king of Babylon, Nabonnedos (555-539 B.C.), particularly devoted to the service of Shamash, enlarging and restoring his temples in Sippar, Larsa and Babylon, and invoking his aid almost to the exclusion of other gods in the political crisis which ended in the advent of Cyrus and in the fall of the neo-Babylonian empire.[12]

The hymns in honor of Shamash, of which we have a large number, belong to the finest specimens of Babylonian and Assyrian literature, celebrating the god as the benefactor of mankind who sheds his light and his warmth in all directions, whose rays ripen the produce of the fields, who is the source of prosperity and of all manner of blessings, who spreads justice, who rewards the virtuous and punishes the wicked and who is also the judge who protects his people, and as a mighty warrior accomplishes the overthrow of the enemy on the field of battle.

A hymn which was evidently composed as a greeting to Shamash as he appears on the horizon begins as follows : [13]

"lord, illuminator of the darkness, opening the face (of heaven),

Merciful god, raising the humble, protecting the weak;

For thy light the great gods wait, All the Anunnaki look for thy appearance,

All tongues [14] dost thou direct as a single being. [15]

With raised heads they look expectantly towards the sunlight;

Thou art the light for the remotest bounds of heaven,

The banner for the wide earth art thou;

All mankind look upon thee with joy."

Briefly but effectively the expectant moments just before sunrise are described, the gods joining with mankind in waiting anxiously for the appearance of the great orb ; and when the tension is released and the light spreads to all sides, all creation is represented as breaking out into joy. No less impressive is the description and praise of the sun at sunset: [16]

"O, Shamash, on thy entrance into the heavens,

May the resplendent bolts of heaven greet thee,

May the gates of heaven bless thee,

May Meshara, [17] thy beloved messenger, direct thee !

Over E-Babbar, the seat of thy rule, let thy supremacy shine,

May A, thy beloved consort, step joyfully before thee,

May thy heart be appeased, [18]

May the table of thy divinity be spread, [19]

O, Shamash, powerful warrior, be thou glorified !

O lord of E-Babbar, pass on, thy course be rightly directed !

Take thy way, on a firm path [20] move along !

O Shamash, judge of the world, giver of all decisions art thou."

We find in all ancient religions a certain fear associated with moments of transition, whether it be the transition of one season of the year to another, or the transition of one phase of the moon to the succeeding one, or the transition of the child from the womb into the light. In accord with this the appearance of the new moon and the time of full moon are fraught with special significance, and similarly in the case of the sun, the moment of sunrise and that of sunset.

Hence the hope expressed in the hymn that the sun may safely enter into the midst of the heavens and be properly directed to pursue the correct path, so as to be certain to make its appearance in the morning at the expected time. If the sun should by any chance lose its way, disaster would follow. Emphasis is laid on the guidance afforded by Shamash. It is he who directs mankind into the right path, just as the sun pursues the right road in moving across the heavens. The right path for mankind is justice, and it is through Shamash as the supreme judge that the cause of the righteous is protected and hidden enemies brought to light.

In the case of a religion unfolding and developing hand in hand with advancing culture, and following more or less closely the political vicissitudes of the country, we must be prepared for the theoretical elaboration of the doctrinal aspects of the current beliefs, by the side of a steady enlargement in the organization of the cult and the priesthood in connection with the chief deities of the pantheon. The result of such a process continued for many centuries is to lead to attempts at a systematization of the currents and counter-currents of popular beliefs. It is part of the system devised by priestly activity to find a place in the pantheon for deities that personify the same power of nature.

The god Ninib, we have seen, absorbed the roles of the other local sun-gods in the earlier Babylonian period, but was obliged to yield his prerogatives to a still greater solar deity, Shamash. Such, however, was the force of tradition that Ninib could not be entirely set aside in favor of Shamash. A place had therefore to be found for Ninib in the pantheon, and this was done by differentiating between the phases of the sun according to the seasons of the year.

The sun in a sub-tropical climate like the Euphrates Valley with only two seasons, a rainy one beginning in the fall and lasting till the spring, and a dry one during the summer months, presents two aspects, as a beneficent and revivifying force in the spring, driving away the rains and the storms and bringing new life in the fields after the apparent extinction of all vitality during the winter months, and as a raging and destructive one during the torrid months when its fierce rays scorch the earth, and the intense heat brings suffering, sickness and often death. Shamash was the sun as a whole, while Ninib became in the theological system of the priests the sun of the springtime, and by a natural association also the morning sun.

The sun as a destructive and hostile force was symbolized by another solar deity, Nergal, who, originally the local deity of an important centre in southern Babylonia, Cuthah, became the sun of the midsummer season and the sun of the noon-time. The cult of Nergal takes us back again to the old Babylonian period when Cuthah [21] was the political focus of one of the principalities in the Euphrates Valley, enjoying an independent existence and exercising sway over a considerable territory, even though the details of the history of the kingdom of Cuthah still escape us. Nergal was too prominent a solar deity to be absorbed by Ninib. His temple at Cuthah, known as E-shidlam, acquired great prominence at an early period.

We find him represented by a shrine or sanctuary at Nippur within the sacred area in which E-kur stood, and when Babylon became the political and religious capital of the country, the cult of Nergal was transferred to this centre and continued in force to the end of the Babylonian monarchy.

Like Ninib and Shamash, Nergal was pictured as a warrior but one of an invariably, grim countenance, a god of battle, whose destructive power was directed against all mankind. True, he also leads his subjects to victory, but more commonly he deals out pestilence and death. He strikes unawares and he strikes apparently without discrimination. He is not a just judge like Shamash, but a god, filled with rage, stalking about in the heat of the day on the lookout for victims. Nergal is thus primarily the god of death. When pestilence sweeps over the land, it is ascribed to Nergal's activity.

Because of this forbidding aspect, it was all the more important to raise one's appeal to him in the hope of averting his wrath. The hymns to Nergal, of which we have quite a number, [22] all emphasize the severity and irresistible power of the god. He is pictured as a lion, which animal becomes his symbol. His solar character crops out in epithets that describe his brilliancy. Like Ninib, he is the son of Enlil who carries out the commands of his father, and as a god of death his presence is naturally felt also in the midst of battle. One of the hymns to him begins as follows: [23]

"Lord, strong, supreme, first-born of Nunammir, [24]

Ruler of the Anunnaki, lord of battle,

Offspring of Kutushar, [25] the great queen,

Nergal, mighty one among the gods, beloved of Ninmenna, [26]

Thou shinest on the brilliant heaven, high is thy station;

Great art thou in the realm of the dead, without a rival art thou;

By the side of Ea, [27] thy counsel is supreme in the assembly of the gods,

With Sin, [28] thou overseest all in heaven.

Enlil, thy father, entrusted to thee, the dark-headed, all living things,

The animals of the field and all swarming creation into thy hand."

The solar character of Nergal is unmistakably revealed in these lines, which also indicate the endeavor to connect the god with other leading figures of the pantheon. As the god of pestilence and death, his special realm, however, is the lower world where the dead are huddled together and which was regarded as a dark, gloomy prison with Nergal and a goddess, Allatu, as the merciless overseers to prevent the escape of any of the prisoners back to the upper world.

There is still another solar deity, originally a local patron of an ancient centre, and who retains his identity in the systematized pantheon by being advanced to the general control of the heavens or the upper regions. This is Anu who is so closely associated originally with Uruk in southern Babylonia as to leave no doubt of his being at the start merely the patron deity of that place. The theoretical aspect of the Babylonian religion to which attention has been directed [29] is illustrated by the position accorded to Anu. He becomes the god of heaven, just as Enlil is placed in control of the earth and the atmosphere above it, and a third deity, Ea, originally the god of the Persian Gulf, becomes the power in control of the watery element in general.

This threefold division of the universe heaven, earth and water With the assignment of one deity to each division is clearly the work of the priestly schools attached to the Babylonian temples. It has an academic flavor. It is only through a phase of speculation which has all the earmarks of the school that the notion arises of the heavens as a distinct section of the universe with some god in general control, just as further speculation of this character leads to the predication of the other divisions of the universe the earth.

With the atmosphere above it and the watery expanse ; and since even the advanced speculation unfolded in the schools adopts the language and metaphors of the animistic view of all nature, the threefold division of the universe leads to assigning to each one a god in control, Anu for the heavens, Enlil for the earth with the surrounding atmosphere, and Ea for the waters.

As the god of heaven, Anu becomes the "king of the gods" and their "father". The triad Anu, Enlil and Ea are invoked at the beginning of votive and historical inscriptions in a manner which shows that the original and specific character of these deities has been entirely lost sight of.

Enlil was chosen as the second figure of the triad because he was the most prominent of the gods whose power was manifested on the earth and in the atmosphere above it, while the choice of Ea as the third member was a similar logical process because he was in control of the greatest body of water known to the Babylonians. As the god of the Persian Gulf, Ea was naturally selected as the personification of the watery element in general.

The conception of Ami as the king and father of all the gods furthermore reflects the period when the seat of the gods was projected on the heavens. Such a view is closely entwined with astrological notions, and rests upon the theory which identifies planets and stars with the gods of the pantheon and quite independent of their original character places the seats of all the gods, the one who presides over the divisions of the drawn up by Babylonian and, later, by Assyrian priests are to a large extent compiled in the interest of the astrological system devised in the schools, and which necessitated designations for a large and ever increasing number of stars.

It is therefore in an astrological sense that Anu is viewed as the king and father of the gods, the one who presides over the division of the universe in which each one of the gods has his assigned station, and since sun and moon are also suspended in the heavens, Anu as the god of heaven is supreme also over the two great orbs of light. In the actual cult of Babylonia, Anu plays a relatively minor part. We do not find hymns and prayers addressed to him, and even in his original seat of worship, it is a goddess, Nana, the personification of the female element in nature, who appears to have been within the period embraced by historical documents the chief object of worship.

In an enumeration of the pantheon, however, in the old Babylonian period Anu is rarely omitted, and, instead of Nana, a consort, Antum, is assigned to him a name representing merely a feminine f orm of the god Anu. All the gods and goddesses being children of Anu and Antum, the name of Anu is often added both in votive inscriptions and in the religious literature in connection with the name of a deity. So for example, Gudea frequently adds to the name Bau, the consort of Ningirsu, that she is the "daughter of Anu" or "the chief daughter" [30] , and even Enlil is designated as the son of Anu. [31] Occasionally instead of the triad, we find only Anu and Enlil enumerated as summing up the manifestation of divine power among mankind.

Ordinarily, however, the third member of the triad is included. As a matter of fact the god Ea is one of the most important as well as one of the most interesting figures in the Babylonian-Assyrian pantheon. He begins his career as the local deity of Eridu, so that he becomes the personification of the watery element in general because the Persian Gulf on or near which Eridu was situated [32] was the largest body of water known to the Babylonians, the "father" of all waters.

The oldest settlements of the Euphrates Valley are those nearest to the Persian Gulf. The part that water plays in the life of mankind and in the development of human culture is quite sufficient to account for the unique position acquired by Ea in the pantheon as the protector of humanity, the friend and guide of man in his career, subject to such constant vicissitudes. He is the teacher also who instructs man in the various arts. [33] It is Ea who endows the rulers with intelligence as it is he who presides over the fine arts, instructing men in architecture, in working precious metals and stones and in all the expressions of man's intellectual activity. Thus Ea may briefly be defined as the god of civilization.

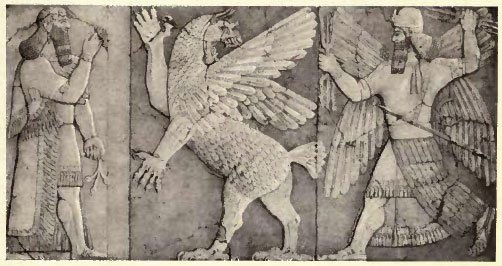

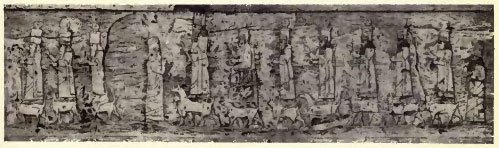

PLATE XXVIII

Fig. 1, The God Marduk in conflict with the monster Tiamat

Fig. 2, Procession of Gods

The friend of mankind, it is to him that one turns in the first instance when other gods seem hostile. When the gods in counsel decide to bring on a destructive rain-storm, it is Ba who reveals the purpose to a favorite of his who by constructing a ship for himself and his family escapes destruction; and similarly in another myth it is Ea who tries to secure immortality for mankind, though he alas ! fails to do so.

The healing qualities of springs, which man must have ascertained at an early period by experience, was no doubt a factor in making Ea a chief figure in the incantation rites for the purpose of driving out the demon supposed to be the cause of disease and bodily suffering. An elaborate exorcising ritual was developed by the priests of Eridu which continued to be down through the period of the Assyrian empire the model and prototype for all other methods of healing disease. The sick man was sprinkled with holy water, and various other rites, symbolizing the hoped for relief from the clutches of the demons or supposed to act directly on the demons, were performed in the name of Ea.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Above, p. 37, seq.

[2]:

Above, p. 135, seq.

[3]:

See Plate LXXV, Fig. 3, and Plate LXXVII, Fig. 1, at the close of Chapter VII.

[4]:

Hilprecht, Old Babylonian Inscriptions, I, 2, No. 87, Col. I, 15-30.

[5]:

A sacerdotal office which, however, also included secular functions.

[6]:

Written Enki. See below, p. 210, seq.

[7]:

I.e., called to his high station.

[8]:

The moon-god, written Enzu. See below, p. 222.

[9]:

A goddess presiding over vegetation.

[10]:

"The lady of the mountain", a title of the consort of Enlil.

[11]:

An otherwise unknown deity.

[12]:

See above, p. 184.

[13]:

Rawlinson IV, 2 PI. 19, Nr. 2.

[14]:

I.e., all peoples.

[15]:

The sun guides all humanity as one directs a single individual.

[16]:

Abel-Winckler, KeUschriftexte zum Gebrauch bei Vorlesungen (Berlin, 1890), pp. 59-60.

[17]:

"Righteousness" — personified as an attendant of Shamash.

[18]:

I.e., may Shamash show himself gracious and not be angry.

[19]:

May rich offerings be placed before Shamash.

[20]:

The "firm path" along which the sun moves is the ecliptic.

[21]:

See above, p. 124, and below p. 455.

[22]:

See Bollenriicher, Qebete und Hymnen an Nergal (Leipzig, 1904).

[23]:

King, Babylonian Magic and Sorcery, Nr. 27.

[24]:

A title of Enlil, conveying the force of "hero of rulership".

[25]:

A goddess.

[26]:

"Lady of the crown" a title of Kutushar, one of the names of the consort of Nergal.

[27]:

The god of humanity.

[28]:

The moon-god.

[29]:

Above, p. 205.

[30]:

E.g., Statue B, Col. 8, 58.

[31]:

By Lugalzaggisi in the inscription above (p. 202) referred to, Col. 3, 16.

[32]:

Owing to the steady accumulation of the soil, Abu-Shahrein, the site of Eridu, is now some sixty miles from the head of the Gulf.

[33]:

Cory, Ancient Fragments, (2d ed.) p. 22, seq.