The civilization of Babylonia and Assyria

Its remains, language, history, religion, commerce, law, art, and literature

by Morris Jastrow | 1915 | 168,585 words

This work attempts to present a study of the unprecedented civilizations that flourished in the Tigris-Euphrates Valley many thousands of years ago. Spreading northward into present-day Turkey and Iran, the land known by the Greeks as Mesopotamia flourished until just before the Christian era....

Part X

The last comer on the field of excavations is the German Orient Society, which, organized in 1900, has the distinction of having conducted its work more thoroughly and more systematically than any of its predecessors, not even excepting de Sarzec's labors at Telloh. The organization of the Society was due largely to the distinguished Prof. Friedrich Delitzsch, who has done more than any other single individual in training a large body of Assyriologists and in arousing popular interest in the civilizations that once flourished in the Euphrates Valley. Among those whose interest he secured was the German Emperor, who has been a generous supporter of excavations in Babylonia and Assyria.

The German Orient Society [1] has not limited its activity to the region of the Euphrates. It has carried on work regularly in Egypt, notably at Abusir and at El-Amarna, and has also carried on some important explorations in Galilee. Until recently the work in Mesopotamia was concentrated on two sites Kaleh-Shergat in the north, representing Ashur, the earliest capital of Assyria, and the mounds in the south that cover the remains of ancient Babylon. Some work has, however, also been done at Fara and Abu Hatab, the sites of Shuruppak and Kisurra respectively, and late in 1912 work was begun on one of the most important ruins of the south, Warka, the name of which still preserves the recollection of the city of Erech or Uruk, the seat of the cult of the goddess Nana which. once flourished there.

The result of fourteen years of steady and uninterrupted excavations has been to reveal in the case of Ashur the history of the city from the earliest period, c. 2000 B.C., to which it can now be traced back, down to the time when it ceased to be the capital of the northern empire and even beyond this period, while in the case of Babylon the excavations have shown that King Sennacherib, of Assyria, did not exaggerate when, in his inscriptions, he told us that weary of the frequent uprisings in the south against Assyrian control, he decided to set an example by completely destroying the city of Babylon razing its large structures to the ground and placing the city under water in order to make the work of destruction complete. This happened in the year 689 B.C. While some remains of the older Babylon, chiefly through the discovery of clay tablets belonging to earlier periods, have come to light, the city unearthed by the German Orient Society is the new city, the creation chiefly of Nebopolassar (625-604 B.C.), the founder of the neo-Ba'bylonian dynasty, and of his famous son, the great Nebuchadnezzar II (604-561 B.C.).

At Ashur the walls, quays and fortifications of the ancient city have been most carefully and methodically excavated and traced on all sides. Already in the earliest days (c. 2000 B.C.) the rulers of the city made it their concern to strongly fortify their stronghold, and as time went on these fortifications grew in massiveness and in strength until, in the days of Shal-maneser III (858-824 B.C.), they reached their highest point of perfection through a series of double walls an inner and an outer one both solidly built with turreited tops and eight huge gates forming the entrances to the city. [2]

Within the city, the remains of various palaces dating from earlier and later periods and of the chief temples of the place as well as considerable portions of the residential section of the city and many graves of the earliest period were thoroughly explored. The method employed by the German explorers, with Walter Andrae and Robert Koldewey as the leaders in the northern and southern fields of activity respectively, was to dig trenches at a distance of a few hundred feet apart, and in carrying them down to the lowest stratum, carefully to follow any leads furnished in doing so. Under such conditions it was hardly possible for any noteworthy contents of the mounds to escape detection. The moment an important structure was struck, work was carried on at that portion of the mound until all that remained of it had been thoroughly explored, after which the combined architectural, archaeological and engineering skill of the exploring party would be brought to bear on the study of the remains and in the efforts at reconstruction.

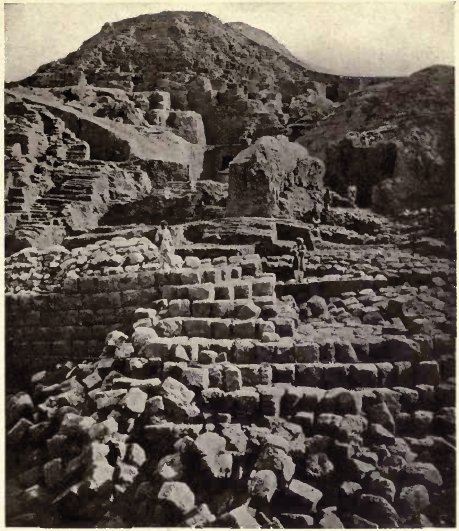

PLATE XVII

Fig. 1, Excavations at Kaleh-Shergat, the site of Ashur.

Fig. 2, Assyrian Memorial Steles.

The huge stage-tower attached to the oldest temple in Ashur, known as E-kharsag-gal-kurra, "great mountain house of all lands", and sacred to the chief deity, Ashur, whose name is derived from that of the place, [3] was uncovered and the foundations of the temple itself traced back to a ruler, Ushpia, who still combined in his person priestly and civic functions. This temple stood near the royal palace, while at some distance away was another sanctuary hardly less famous, and which is constantly referred to in the annals of the Assyrian rulers. It bore a double name "the temple of Ami and Adad" and proved to be a double construction with a common exterior court. [4]

With the help of a large number of inscribed bricks and clay cylinders found within the temple enclosure, we can trace the work done on the structures by the many rulers anxious to show their devotion to Ami and Adad through additions to the temple or through repairs. An interesting feature of the cult at Ashur in later days as revealed through the excavations, [5] has been the finding of a "festival house" referred to in the inscriptions of Sennacherib to accommodate the multitude that made a pilgrimage annually to the sacred city to celebrate the New Year's festival occurring in the spring under the shadow of the temples.

Besides unearthing various temples and palaces, the German expedition has also uncovered a portion of the residential quarter of the city and has given us, for the first time, a closer view of the manner in which the people lived. Entire rows of private houses have been dug out ; they were on the whole of a very simple brick construction, consisting of one story, and a series of rooms grouped around a central court, which was open to the sky. Ordinarily the houses were quite small, but larger ones have also been found consisting of a large outer court, leading into a long room, at the end of which there was a passageway, giving access to an inner court around which a large series of rooms, varying in size, were grouped, while the back part of the house again consisted of a long room like the corresponding one at the end of the outer court.

A notable discovery made in the space between the outer and inner walls of the city and with which we must close our account was that of a large series of steles of various material alabaster, basalt, limestone, sandstone and composite material containing commemorative inscriptions of rulers and their consorts and of high officials. [6] No less than 140 of such steles were found, many in a fragmentary condition, but enough in a sufficiently preserved state to enable us to say that these monuments varied in height from about six to seven feet.

They were generally rounded at the top and some contained, in addition to the commemorative inscription, a sculptured image of the individual in whose honor the monument was erected. The names of no less than twentyfive rulers of Assyria are revealed through thesg steles. Besides these twenty-five rulers, we have steles of three "ladies of the palace", including the famous Semiramis, who turns out to be the "palace lady" of Shamshi-Adad IV (or V), who ruled from 823 to 811, and further designated in the accompanying inscription as the mother of King Adad-nirari IV (810-782) and the daughter-in-law of Shal-maneser III (858-824 B.C.). Of officials represented by monuments, the names of fortyfour are preserved in whole or in part.

The monuments of the kings and their consorts were found near the inner wall, those of the officials near the outer wall. The steles range from c. 1400 B.C. to the days of Ashurbanapal (668-626 B.C.), that is to say within twenty years of the fall of the Assyrian Empire. It is evident that these monuments were erected by the rulers themselves and set up in a place of honor, and it is a reasonable conjecture that those of the officials were erected by their royal masters in recognition of their services to the state or to the royal house. There has thus been revealed the custom in ancient Assyria of erecting monuments in public places.

In Babylon, where the work was conducted chiefly under the superintendence of Dr. Robert Koldewey [7] for an equally long period as at Ashur, the chief efforts of the German explorers were directed to the mound Kasr, the name of which, viz.: "fortress", preserved the tradition of the royal palace built by Nebopolassar and considerably enlarged by Nebuchadnezzar, that once stood there, and to the mount Amran, the southern of the three mounds which covered the ancient city and which proved to be the site of the famous temple, E-sagila, "the lofty house", sacred to the chief god of Babylon and the head of the Babylonian pantheon after the days of Hammurapi, the supreme Marduk.

The entire foundations of the palace were uncovered, the hundreds of rooms that it comprised, traced, and a most careful study made of every detail that was brought to light. Of great importance were the discoveries made in the space between the palace and the chief temple. A sacred procession street was laid bare, a via sacra built high above the low houses of the city and along which the images of the numerous gods and goddesses, who formed a court around Marduk, were carried in procession on festive occasions, and more particularly on the New Year's day, which was the most solemn occasion of the year.

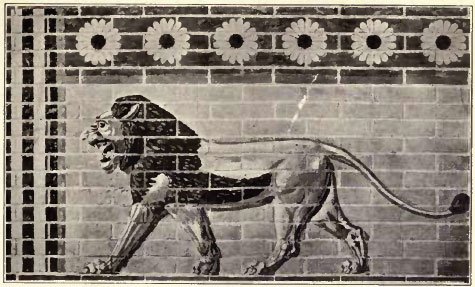

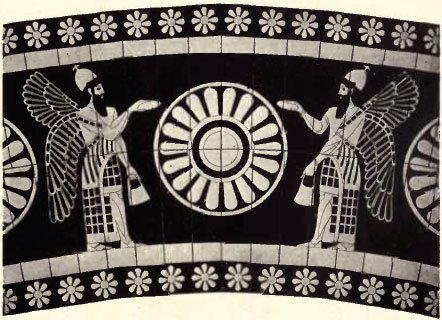

The walls along this street were lined with glazed tiles representing a series of lions, surmounted by rows of rosettes and other ornamental designs. The street was paved with large blocks of a composite material and contained at frequent intervals a dedicatory inscription indicating the name of the street as "Aibur-shabu", "may the enemy not wax strong", and the name of the builder as the great Nebuchadnezzar. [8] A magnificent gateway, known as the Ishtar gate and consisting of an outer and inner gate, formed the approach to the street. The six square towers of the gateway contained on all sides a series of glazed tiles with alternate representations of horned dragons and unicorns, so arranged that a group of dragons running as a pattern around the four sides of the tower was succeeded by a group of unicorns similarly arranged.

It was found that there were eighteen such alternate groups, one above another. The effect of these brilliantly illuminated high facings of the towers must have been superb (see Plate XXXVII). Surrounding the chief temple to Marduk that was uncovered beneath the mound Amran, stood numerous smaller temples and shrines in honor of the many gods and goddesses who were worshipped at Babylon and whose relationship to Marduk was that of members of the royal family, ministers and courtiers to the king, as the supreme chief. Nebuchadnezzar, in his inscriptions, enumerates some forty such structures within the sacred precinct which, from the name of Marduk 's temple, was known as E-sagila.

Unfortunately the condition in which these temples were found was most lamentable, so that little of their decoration and of their varied contents could be determined. Lastly, as at Ashur, a great part of the efforts of the expedition was directed to tracing the walls the outer and inner walls and the extensive fortifications of the city as begun by the founder of the Neo-Babylonian dynasty and continued by his great son. [9]

PLATE XVIII

Fig. 1, The Lion of Babylon

Fig. 2, Archway of colored, glazed tiles (Khorsabad)

Quite a number of inscriptions have been found in connection with the temples, and also several hundred business documents, chiefly of the Persian period, but there is every reason to believe that the soil still holds quantities of literary treasures from the archives of the great Marduk temple, which even in the neo-Babylonian period must have been extensive.

Extending their activities to Borsippa close to Babylon, but on the other side of the Euphrates the German expedition has been successful in coming across the chief temple, E-zida, "the legitimate house", sacred to Nabu, the son of Marduk, and in tracing the outlines and interior arrangement of that edifice which played a part only second in importance to that of E-sagila, in Babylon.

Here we may rest our survey of the work done at the mounds. The seventy years intervening between the first larger efforts inaugurated by Botta and the present date have been marked, as we have seen, by a truly astonishing activity on the part of English, French, American and German explorers, as a result of which many of the most important sites of Babylonia and Assyria have been laid bare, and a large number of others, though only partially excavated, have been identified.

Palaces and temples, towers and archives, private houses and graves, walls and fortifications have been dug up from beneath the mounds so that we are in a position to reconstruct the appearance that the ancient cities of the south and north must have presented. An enormous amount of archaeological material in the form of sculptured reliefs, statues, pottery of all kinds, jewelry, instruments, thousands of seal cylinders with designs representing adoration scenes, sacrificial scenes, illustrations from myths, etc., works of art of all kinds have been secured through which we are enabled to fill out the picture of the civilization of the Euphrates and Tigris with innumerable details.

We can follow their methods of warfare, their daily life, the construction of their public and private buildings, their ideals of art and their religious beliefs. Still more extensive and even more valuable as furnishing the key to an understanding and full appreciation of those ancient civilizations is the yield through the excavations of inscribed material inscriptions on bas-reliefs, statues, votive offerings and other monuments and of the tens of thousands of clay tablets of all periods from the earliest to the latest, forming the business and legal records of the temple administration, and of private transactions of all kinds, and lastly the literary collection of some thirty thousand tablets or fragments of tablets, found in the royal palace at Nineveh, supplemented by thousands of tablets, likewise with literary contents, discovered among the remains of archives of the temples of the south.

These invaluable treasures scattered throughout the public and private museums of Europe and America have for the greater part been made accessible through publications, and as new material is found it is published as speedily as possible. Through the interpretation of this inscribed material the oldest portion written in characters approaching the picture stage of writing, but soon yielding to a cursive style in which the original pictures assume the form of wedges the work of recovering the lost story of Babylonia and Assyria has been supplemented and completed.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Accounts of the work are published in the Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orientgesellschaft, published at intervals of every two or three months, while texts and more detailed reports and investigations are given in an important series known as the Wissenschaft liche Veroffentlickungen der Deutschen Orientgesellschaft, of which, up to the present, eighteen substantial volumes have been issued.

[2]:

See W. Andrae 's magnificent work, Die Festungswerke von Assur (Leipzig, 1913), 2 vols., with several hundred illustrations and plates.

[3]:

He is the god of the city of Ashur and then becomes simply Ashur. See the writer's article, "The Go4 Ashur," in the Journal of the Am. Or. Soc., 1903, pp. 283-311.

[4]:

See the detailed account in Andrae 's Der Anu-Adad Tempel (Leipzig, 1909), and see Plate XXXIX, Fig. 1.

[5]:

See Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orientgesellschaft, Nr. 33.

[6]:

See the publication of the German Orient Society, by Andrae, Die Stelenreihen in Assur (Leipzig, 1913)

[7]:

See the summary of the results by Koldewey, Das Wieder-Erstehende Babylon (Leipzig, 1913). English translation by Agnes S. Johns, under the title, The Excavations at Babylon (London, 1914)

[8]:

See Koldewey, Die Pflastersteine von Aiburschabu (Leipzig, 1901).

[9]:

See Koldewey, Die Tempel von Babylon und Borsippa (Leipzig, 1911).