The civilization of Babylonia and Assyria

Its remains, language, history, religion, commerce, law, art, and literature

by Morris Jastrow | 1915 | 168,585 words

This work attempts to present a study of the unprecedented civilizations that flourished in the Tigris-Euphrates Valley many thousands of years ago. Spreading northward into present-day Turkey and Iran, the land known by the Greeks as Mesopotamia flourished until just before the Christian era....

Part VIII

In 1877 the French Vice consul at Basra, Ernest de Sarzec, began a series of excavations in a series of mounds at Telloh, in the extreme southern section of the Euphrates Valley, selected, by him after a reconnoitering tour as a most promising locality. With short interruptions these excavations were continued by de Sarzec until his death, in 1901, and since that time under the guidance of Graston Cros.

Of the series of mounds at Telloh there were two which attracted particular attention, each rising about fifty to sixty feet above the plain. De Sarzec began his work at the smaller of the two and soon came upon the remains of an extensive palace which, however, turned out to be a late construction [1] belonging to about the beginning of the third century B.C. Along with evidence of a late construction, indications of a very early edifice were found, and the interesting problem thus raised was finally solved by the definite proof that the palace, dating from Parthian times, and following in its general construction the model of Assyrian palaces, was erected on the site of an ancient Babylonian temple, the material of which was partly used in the late construction. The substratum was erected, in accordance with a practice that was thus shown to be a trait of the architecture of the region from the earliest to the latest period on an immense terrace, about forty feet high, while the expanse itself covered some 600 feet square. The older building, which alone interests us proves to be a temple of large proportions and dedicated to Ningirsu, the patron deity of Shirpurla (or Lagash), which was thus identified as the city covered by the mound Telloh. [2] The foundation of the temple can be traced back to Urukagina (c. 2700 B.C.), and may be several centuries older even than this ruler. It was an object of veneration to all rulers of the city and acquired a significance that prompted rulers of other centres to leave traces of their devotion to Ningirsu, through enlarging the dimensions of the temple or to through repairs of portions that had fallen into decay.

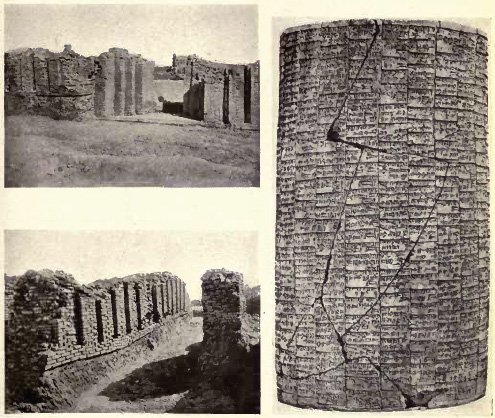

PLATE XII

Fig. 1 and 2 (left-top and left-bottom), Excavations at Telloh

Fig. 3 (right), Inscribed Terra-Cotta cylinder from Telloh

Little was left, however, of the old temple beyond a wall at the east corner, which formed part of the work done by Ur-Bau (c. 2450 B.C.), and a tower and gate constructed by Gudea about a century later, and some layers of bricks in various sections. In the course of the excavations, however, a large number of remarkable monuments were found, and a truly astonishing array of miscellaneous objects, inscribed vases, seal cylinders, bas-reliefs, bronze votive offerings, pottery, iron utensils, terra-cotta cylinders, and inscribed cones. Chief among these were nine magnificent diorite statues of Gudea, in whose days Shirpurla, although no longer forming an independent state, enjoyed a second period of grandeur. These statues, representing the ruler in sitting posture or standing, were covered with inscriptions indicating that they were set up as votive offerings. Gudea in thus placing statues of himself in the sacred edifice followed the example of Ur-Bau, of whom likewise an inscribed statue was found. The stone, as Gudea tells us in his inscriptions, was brought from a distant land, as he brought copper and gold and precious woods from various parts of Arabia and cedars from northern Syria. Such intercourse with distant lands is an illustration of the commercial activity prevailing at that early period.

The interest aroused in France through the arrival of the statues at the Louvre was sufficient to ensure further grants from the French government to continue the excavations. The inscriptions proved to be couched in the old Sumerian language spoken by the non-Semitic inhabitants who in the earliest period were in control of the region. When they came to be deciphered, they threw a new light on early political conditions in the Euphrates Valley, and our knowledge of those conditions was still further increased through the intercontaining about 2000 lines, which furnished us with pretation of the two large terra-cotta cylinders, each detailed information regarding Gudea's plans in the construction of E-ninnu, how he was prompted to undertake this work at the direct instance of Ningirsu, who appeared to him in a dream and gave him instructions how to proceed. The picture of the earliest culture in the south now grew more distinct and it became evident that Assyrian culture was only an extension of the civilization that arose in the south. It was therefore in the southern mounds that the origin of the civilization of the region was to be sought, and as a consequence the activity of exploring expeditions since de Sarzec's days was largely directed to the mounds in the south. The work at Telloh was by no means limited to the illustration of the days of Gudea. Monuments were found taking us back far beyond this period, as, e.g., the fragments of an elaborate sculptured votive offering, showing on the one side the god Ningirsu with the double-headed eagle, the standard of Shirpurla, in one hand and a great net in the other, in which he has gathered the heads of the enemy. [3] The accompanying inscription told the story of the conflict against the people of Umma, the triumph of Eannatum (c. 2900 B.C.) and the agreement made between the contesting parties. [4]Another monument, likewise a votive offering, dating from the days of Eannatum's grandfather Ur-Nina, who placed a tablet of sandstone in the great temple of Ningirsu, inscribed with his name and titles and exhibiting a lion-headed eagle clutching a lion with each of its talons. [5]

PLATE XIII

Fig. 1, Diorite statue of Gudea (C. 2450 B.C.)

Fig. 2, Standing statue of Gudea

Other votive offerings were of bronze and represented a kneeling deity holding a pointed cone, others again crouching bulls surmounting a pointed cone, female or male figures bearing baskets on their heads and covered with dedicatory inscriptions, or statuettes terminating in a point.

In the second of the two larger mounds de Sarzec was no less successful. Eemains of buildings of various dates were unearthed, all of which seemed to have served some purpose connected with the great temple, such as smaller shrines for the deities worshipped at Lagash, forming the court around Ningirsu, storerooms, granaries and perhaps archive chambers, as well as dwellings for some of the many officials connected with the constantly growing temple administration. Many valuable monuments were likewise found in this mound. Prominent among these was a superb silver vase, delicately incised with representations, running around the vase, of lion-headed eagles clutching lions, ibexes and deers, while the upper portion depicts a series of crouching bulls. The accompanying inscription tells us that the vase, which is one of the finest specimens of Babylonian art and reveals the high development reached in very early days, was an offering made by Entemena, a ruler of Shirpurla, whose date is about 2850 B.C., and who was a son of Eannatum, to whom we owe the monument above described, which is commonly known among archaeologists as the "Stele of Vultures". A series of three limestone votive tablets showing Ur-Nina, a ruler of Shirpurla (c. 3000 B.C.), accompanied by his children, is of special interest in revealing to us an array of Sumerian types and further details of the Sumerian mode of dress. [6]

Our knowledge of the remarkable art of the earliest period was further enriched through the discovery of such objects as an elaborately sculptured pedestal in dark green steatite, forming the support to some large piece and showing seven small squatting figures distributed around the pedestal, a mace-head elaborately carved, dedicated by a King Mesilim of the city of Kish (c. 3100 B.C.), a large spear-head of copper about two and a half feet long and dedicated to Ningirsu by another ruler of Kish, superb lion heads carved in limestone and serving a decorative purpose, libation bowls and sculptured placques of various kinds, round trays in veined onyx, furnishing additional names of rulers of Lagash, an unusually large bas-relief in limestone, over four feet high and representing priests and a musician playing a harp of eleven strings, the whole being again a votive offering for the ancient temple. [7] Through such objects as well as through the various designs on seal cylinders,[8] of a religious character or illustrating episodes in myths and popular tales, a further insight into the religious life and beliefs was afforded, the forms and features given to the various gods and goddesses, their symbols, the style of their altars, the kind of sacrifices offered to them, and the various phases of symbolism in the cult. Supplemental to the monuments, to the works of art, and to the votive and historical inscriptions, de Sarzec was fortunate enough to discover in another section of the mounds the extensive temple archive of clay tablets, dealing with the administration of the temple property and the commercial affairs of the temple officials. The tablets were arranged in layers, evidently according to some system so that any particular one could readily be picked out In all, some 30,000 tablets were found, but the greater portion were stolen by the natives during de Sarzec's absence and falling into the hands of dealers are now scattered throughout the museums of Europe and this country, and in private hands.

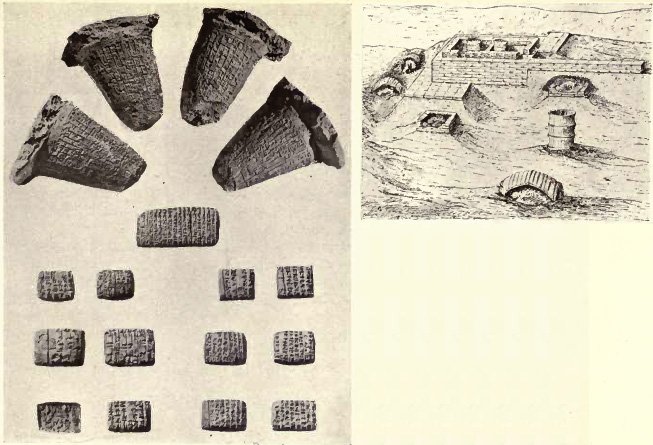

PLATE XIV

Fig. 1, Specimens of tablets and inscribel cones from Telloh

Fig. 2, Necropolis at Telloh

Many thousands have now been published, from which we have secured a detailed view of the extent of temple activity and the methods of temple administration in early Babylonian days. The new series of excavations also resulted in discovering the section of the ancient city in which the dead were buried. A considerable portion of the necropolis has been laid bare, showing for the first time the arrangement of an ancient Babylonian cemetery, and incidentally settling a hitherto disputed point whether burial constituted the oldest form of disposing of the dead in the Euphrates Valley. No traces of cremation were found, but the methods of burial were not uniform. Some of the graves were square vaults into which the bodies were sunk, others were shaped somewhat like barrels, within which the bodies were placed.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Shown by inscribed bricks bearing the name of Hadad-nadin-akhe in Aramaean and Greek characters.

[2]:

Telloh means the "mound of tablets", and thus preserves the tradition of the temple archive which was discovered by de Sarzec and which formed one of the features of the temple area.

[3]:

See the comprehensive work by Ernest de Larzec et I/Son Heuzey, Decouvertes en Chaldee (Paris, 1884^1912) followed by Gaston Cros, Leon Heuzey et Frangois Thureau-Dangin, Nouvelles Fouilles de Tetto (Paris, 1910).

[4]:

See the recent publication of Leon Heuzey et F. Thureau-Dangin, Restitution Materielle de la Stele des Vautours (Paris, 1909). See Plates XLVII and XLVIII.

[5]:

See Plate XLIX, Fig. 1.

[6]:

Plate XL VI, Fig. 1; Plates LXIII and LXIV for votive statuettes, above referred to; and Plate LXXI, Fig. 1, for the silver vase of Entemena.

[7]:

See Plate XLV, Fig. 2, and Plate LIII for the lion heads.

[8]:

See at the close of Chapter VII, and Plate LXXV-LXXVII.