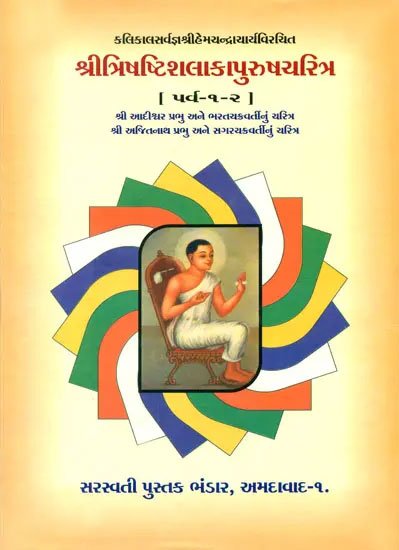

Trishashti Shalaka Purusha Caritra

by Helen M. Johnson | 1931 | 742,503 words

This page describes Sumangala and the ascetic which is the second part of chapter VI of the English translation of the Mahavira-caritra, contained within the “Trishashti Shalaka Purusha Caritra”: a massive Jain narrative relgious text composed by Hemacandra in the 12th century. Mahavira in jainism is the twenty-fourth Tirthankara (Jina) and one of the 63 illustrious beings or worthy persons.

Part 2: Sumaṅgala and the ascetic

Now, in this same Bharata, in the town Vasantapura, there was a king suitably named Jitaśatru. His chief-queen, Amarasundarī, was like a goddess who had come to earth, a mine of the jewels of virtues. They had a son, named Sumaṅgala, the dwelling-place of felicity, a Kandarpa in beauty, a depository of the arts, like the moon of digits. There was a minister’s sons of the same age, named Senaka, a supreme example of all bad characteristics. He had tawny hair, like a mountain whose peak was blazing with a forest-fire; he was flat-nosed like an owl and yellow-eyed like a cat; his lips and neck were pendulant like a camel’s; his ears small like a mole’s; he had a row of teeth outside (his lips) that had the appearance of shoots from the bulb of his mouth; he was big-bellied like a person with dropsy; his thighs were small like a domestic pig’s; his shanks bowed as if by a round seat; his feet bigger than a winnowing basket.

Wherever the misshapen wretch went, there laughter attained sole command. Prince Sumaṅgala laughed at him coming, even at a distance, as if he had seen a deformed clown. Ridiculed thus by the prince day and night, Senaka felt disgust with existence, the great fruit of the tree of contempt. Then the unfortunate Senaka, with disgust with existence produced, left the city, vacant-minded like an insane person.

After some time while the minister’s son was away, Prince Sumaṅgala was established by his father on his throne. In his wandering Senaka saw an abbot in the forest, became an ascetic at his side, and took the uṣṭrikā-vow.[1] Constantly and excessively tormenting himself by severe penance, one day he went to that same Vasantapura with the ascetic (his guru). All the people honored him, saying, “He is a minister’s son and an ascetic.” Questioned about the reason for his disgust with existence, he explained:

“Prince Sumaṅgala laughed at this figure of mine. Because of that my disgust with existence was born, earnest-money of a wealth of penance.”

King Sumaṅgala heard that and went to pay respect to him, begged for forgiveness, and invited him cordially for breaking his fast. He gave the king a blessing and consented to his request. The king went to his house like one who has accomplished his desire.

When a month's fast had been completed recalling, the king's invitation, the ascetic, tranquil in mind, went to the palace-door. At that time the king was not well. A doorkeeper shut the door. Who looks at a mendicant monk then? He was blocked by the door-closing like a flow of water by a dam. The ascetic returned by the same road by which he had come. Deciding on a month’s fast, he went back to the jar. He was not angry. Great sages rejoice at an increase in penance.

The king, who had recovered, devoted to ascetics, went the next day, bowed, asked his forgiveness, and said to him:

“I invited you for merit, but demerit was acquired. Generally, demerit alone is the guest of those living in sin. I prevented your breaking fast elsewhere, Blessed One. Friendly speech of one who does not give creates an obstacle for receiving elsewhere. At the fast-breaking of the second month’s fast, please adorn my courtyard like a kalpa tree Nandana.”

The ascetic agreed and the king went home. He kept counting on his fingers the day for fast-breaking. When the month’s fast was completed, the ascetic went to the palace. By chance the king was ill as before. The door being shut in the same way, he turned away and went to the jar. When the king had recovered, he invited him as before.

When the third month’s fast had been completed, the ascetic went in the same way and the king was ill again in the same way. The King’s servants thought, “Whenever this ascetic comes, then our Master becomes really ill.” They instructed the guards, “This ascetic, the minister’s son, must be thrown out, even as he enters, like a serpent.” The guards did just so and the ascetic made a nidāna, “May I be instrumental in the destruction of this king.” The ascetic died and was born as a Vānamantara of little magnificence. The king too, having become an ascetic, reached that same status. Sumaṅgala fell and was born the son of King Prasenajit, named Śreṇika, borne by Dhāriṇī.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

‘Sādhu of Ājīvika-faith who practices penance by sitting in a large jar.’ PH, s.v. uṭṭiyāśamaṇa.