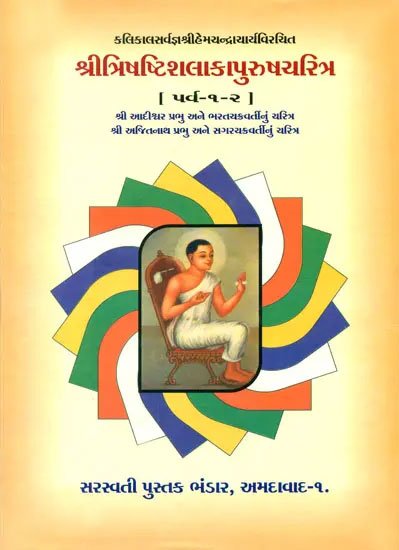

Trishashti Shalaka Purusha Caritra

by Helen M. Johnson | 1931 | 742,503 words

This page describes Ravana’s lineage (vamsha) which is the second part of chapter I of the English translation of the Jain Ramayana, contained within the “Trishashti Shalaka Purusha Caritra”: a massive Jain narrative relgious text composed by Hemacandra in the 12th century. This Jain Ramayana contains the biographies of Rama, Lakshmana, Ravana, Naminatha, Harishena-cakravartin and Jaya-cakravartin: all included in the list of 63 illustrious beings or worthy persons.

Part 2: Rāvaṇa’s lineage (vaṃśa)

At the time that the Arhat Ajita was wandering (over the earth), Ghanavāhana was the bulb of the Rakṣas-line in Laṅkā on the Rakṣodvīpa in this same Bharata. He, very wise, settled his kingdom on his son, Mahārakṣas, became a mendicant at the feet of Ajita Svāmin, and attained emancipation. After he had enjoyed the kingdom for a long time, Mahārakṣas also bestowed it on his son, Devarakṣas, became a mendicant, and attained emancipation.

After innumerable lords of Rakṣodvīpa had come and gone thus, Kīrtidhavala was lord of the Rākṣasas in the congregation of Śreyāṃsa.

At that time there was a renowned king of Vidyādharas, Atīndra, in the city Meghapura on Mt. Vaitāḍhya. By his wife, Śrīmatī, he had a son, Śrīkaṇṭha, and a daughter, Devī, like a goddess in beauty. The Vidyādhara-lord, Puṣpottara, lord of Ratnapura, asked the fair-eyed maiden in marriage for his son Padmottara. By the decree of fate, Atīndra did not give her to him, though he was meritorious and distinguished, but he gave her to Kīrtidhavala. When King Puṣpottara heard that she was married to Kīrtidhavala, he, a destroyer of arrogance, became hostile to Atīndra and Śrīkaṇṭha.

One day, the daughter of Puṣpottara, Padmā, like (the goddess) Padmā in beauty, was seen by Śrīkaṇṭha as he returned from Meru. Mutual affection, a cloudy day for the excessive brilliance of the ocean of the emotion of love, sprang up at once between Śrīkaṇṭha and Padmā. The maiden stands with the lotus of her face turned up to Śrīkaṇṭha, as if throwing a svayaṃvara-wreath with affectionate glances, śrīkaṇṭha discerned her desire and, suffering from love, seized her and quickly started to fly through the air. “Some one is carrying off Padmā,” the servants screamed. Powerful Puṣpottara armed himself and pursued them with an army. Śrīkaṇṭha took refuge promptly with Kīrtidhavala[1] and gave him a complete account of the kidnaping of Padmā. Puṣpottara soon arrived there, covering the directions with troops in solid ranks, like the ocean covering the earth with water at the end of the world. Kīrtidhavala sent word by a messenger to Puṣpottara: “This preparation for war has been made needlessly without reflection. The maiden must surely be given to some one. If she herself has chosen Śrīkaṇṭha, then he is not at fault. Therefore it is not suitable for you to fight; but, rather, after learning your daughter’s intentions, it is fitting for you to celebrate now the wedding-rites of the bride and groom.” Just at that time Padmā sent word by a female-messenger: “I chose him, myself. He did not abduct me.” Upon hearing this, Puṣpottara was instantly appeased. Certainly, the anger of persons who know correct conduct is usually easily appeased. After he had celebrated the wedding of Śrīkaṇṭha and Padmā with a great festival, Puṣpottara went to his own city.

Kīrtidhavala said to Śrīkaṇṭha: “You stay here, since you have many enemies on Mt. Vaitāḍhya now. Not far to the northwest of this very Rākṣasadvīpa, there is Vānaradvīpa, three hundred yojanas long. There are other islands of mine, too, Barbarakūla, Siṃhala, and others, that resemble pieces of heaven that have fallen to earth, my friend. In some one of them, establish your capital and stay with me in comfort, not separated because of the close proximity. Even if you do not have the least fear of your enemies, nevertheless you can not leave from fear of separation from me.” Urged affectionately by him in this way and very fearful of separation from him, Śrīkaṇṭha agreed to live on Vānaradvīpa. After he had founded his capital, named Kiṣkindhā, on Mt. Kiṣkindha on Vānaradvīpa, Kīrtidhavala installed him in his kingdom. King Śrīkaṇṭha saw many monkeys roving about on the island. They were handsome, with large bodies, and lived on fruit. He proclaimed that they should not be killed and had food, drink, et cetera given them. Others, also treated them well. Like king, like subjects. From that time on for amusement the Vidyādharas made monkeys both in paintings and plaster models and in insignia on banners, umbrellas, et cetera. The Vidyādharas who lived there were called Vānaras (Monkeys) from the kingdom of Vānaradvīpa and from the monkey-insignia.

A son, named Vajrakaṇṭha, was born to Śrīkaṇṭha. He was zealous in the sports of battle, his strength unblunted in them all.

As Śrīkaṇṭha was sitting in his own assembly-hall, he saw the gods going to Nandīśvara for a festival to the eternal Arhats. As a horse on a village-road follows horses going on the highway, he, full of devotion, followed the gods. As he was going, his aerial car stumbled on Mānuṣottara, like the current of a river on a mountain which was on its course. “I must have performed little penance in a former birth. For that reason my desire for the Arhats’ festival in Nandīśvara was not fulfilled.” Attaining disgust with existence at that thought, he became a mendicant at once, practiced severe penance, and went to emancipation.

Since the time of Śrīkaṇṭha many kings had come and gone, Vajrakaṇṭha and others. At the time of the congregation of Munisuvrata Ghanodadhiratha was king. At that time in the city Laṅkā there was a lord of the Rākṣasas, named Taḍitkeśa. Between these two there was a strong friendship. One day, Taḍitkeśa went with the women of his household to sport in a choice garden, named Nandana. While Taḍitkeśa was engaged in sport, a monkey descended from a tree and scratched the breast of Śrīcandrā, Taḍitkeśa’s chief-queen, with his nails. His hair standing on end from anger, Taḍitkeśa struck the monkey with an arrow. For injury to women is not to be endured. Injured by the blow with the arrow, the monkey went a short distance and fell at the feet of a sādhu engaged in pratimā. He gave him the namaskāra,[2] provisions for the journey to the next world. By its power he became an Abdhikumāra after his death. Knowing his former birth by clairvoyance he approached the sādhu and paid homage to him. For the sādhu who confers benefits is especially to be honored by the noble.

He saw other monkeys being killed by Taḍitkeśa’s soldiers and at once blazed with anger. He created (by magic) many figures of large monkeys and attacked the Rākṣasas, overwhelming them with masses of trees and stones. Recognizing that it was the device of a god, Taḍitkeśa worshipped him ardently and said: “Who are you? Why do you attack us?” Then the Abdhikumāra, his anger appeased by the worship shown him, related the slaughter of himself and the power of the namaskāra. Laṅkā’s lord and the monkey together approached the sādhu and asked, “Lord, what is the reason for the monkey’s hostility toward me?” The ascetic related: "You were formerly a minister’s son, named Datta, in Śrāvastī; he was a hunter in Kāśi. One day, after you had adopted mendicancy, you were going to Vārāṇasī. He saw you and killed you, struck by the thought, ‘That is a bad omen.’ You became a god in Māhendrakalpa and, when you fell, were born here, such as you are. He passed through a hell-birth and became a monkey. This is the reason for the enmity.”

After paying homage to the great sādhu, a universal benefactor, and taking leave of the lord of Laṅkā, the god departed. After hearing that, Taḍitkeśa bestowed his kingdom on his son, Sukeśa, became a mendicant, and went to the final abode. Ghanodadhiratha bestowed the kingdom, Kiṣkindhā, on his son, named Kiṣkindhi, took initiation, and attained emancipation.

Now in the city Rathanūpura on Mt. Vaitāḍhya at that time there was a Vidyādhara-king, Aśanivega. He had a son, Vijayasiṃha, victorious, and a second, Vidyudvega, like additional arms for him. On that same mountain, in the city Ādityapura there was a Vidyādhara-king, Mandiramālin, and he had a daughter, Śrīmālā. He summoned the kings of the Vidyādharas to her svayaṃvara and they sat on the daises like constellations above celestial palaces, Śrīmālā brushed the chiefs of the Vidyādharas, as they were described by the female doorkeeper, with her glance, like a canal brushing trees with water. Passing over all the other Vidyādharas in turn, she came to a stop before Kiṣkindhi, like Jāhnavī before the ocean. Śrīmālā threw around his neck the groom’s garland which was like a priceless pledge for the future embrace of the creeper of her arm. Then Vijayasiṃha, addicted to rashness like a lion, his face terrifying from frowns, said aloud angrily:

“These men, always of bad character, were formerly banished from the capital of Vaitāḍhya, like thieves from a good kingdom. By whom were these men, of bad character, of low family, brought here? To make sure they will never return, I shall kill them today like cattle.” After saying this and standing up, powerful, resembling Yama, he advanced, raising his weapon to kill King Kiṣkindhi. The Vidyādharas, not to be restrained from heroic deeds, rose up for battle. Some, Sukeśa and others, were on Kiṣkindhi’s side; others were on Vijayasiṃha’s side. Then a battle started, cruel as the end of the world, with the sky sparkling with elephants engaged tusk against tusk; with horsemen meeting, lance against lance; with charioteers meeting, arrow against arrow; with infantry attacking, sword against sword; with the ground muddy with blood. After they had fought for a long time, Andhaka, Kiṣkindhi’s younger brother, made Vijayasiṃha’s head fall, like a fruit from a tree, by means of an arrow. The Vidyādhara-lords, Vijayasiṃha’s followers, were terrifed. Whence is there courage for people without lords? Verily, a leaderless army is defeated.

Kiṣkindhi took Śrīmālā along, like the Śrī of victory in person, flew up, and went to Kiṣkindhā with his followers. When he heard the news of his son’s death, which was like a stroke of lightning from the sky, Aśanivega hastened to Mt. Kiṣkindhi. He surrounded the city Kiṣkindhā with many soldiers, like the stream of a river surrounding the high ground of a large island with water. The heroes, Sukeśa and Kiṣkindhi, came out of Kiṣkindhā with Andhaka, eager to fight, like lions from their den. Then Aśanivega, very impatient, a hero, regarding the enemy as straw, began the battle with an attack with the whole army. Then in the front line of battle, blind with anger, Aśanivega, powerful, cut off the head of Andhaka who was the lion to the elephant of Vijayasiṃha. Then the monkey-soldiers with the Rākṣasas ran in all directions like a mass of clouds scattered by wind. The leaders of Laṅkā and Kiṣkindhā went to Pātālalaṅkā with their wives and retinues. Sometimes retreat is strategy. When he had struck down his son’s murderer, like an elephant a driver, the anger of the King of Rathanūpura was appeased. Delighted with the destruction of his enemies, he, the authority for setting up kings, installed a Vidyādhara, named Nirghāta, on Laṅkā’s throne. Then King Aśani returned to his city Rathanūpura on Vaitāḍhya, like the king of the gods to Amarāvatī.

One day King Aśanivega, in whom a desire for emancipation had arisen, bestowed the kingdom on his son, Sahasrāra, and took initiation. In the city Pātālalaṅkā sons were borne to Sukeśa by Indrāṇī—Mālin, Sumālin, and Mālyavat. Two long-armed sons, named Ādityarajas and Ṛkṣarajas, were borne to Kiṣkindhi by Śrīmālā. One day, Kiṣkindhi made a procession to Sumeru in honor of the eternal Arhats and on his return he saw Mt. Madhu. Kiṣkindhi’s mind dwelt more and more on sporting in a beautiful garden, which extended in all directions on it like another Meru. He, energetic, founded Kiṣkindhapura on it (Mt. Madhu) and settled there with his followers, like the King of Yakṣas (Śiva) on Kailāsa.

When Sukeśa’s sons heard that their kingdom had been taken by enemies, they, full of heroism, flamed with anger like three fires. They went to Laṅkā and killed the Khecara, Nirghāta. Verily, enmity with heroes may result in death even after a long time. Then Mālin became king in Laṅkā and Ādityarajas king in Kiṣkindhā at Kiṣkindhi’s command.

Now, in the city Rathanūpura on Mt. Vaitāḍhya a god of high rank fell and descended at once into the womb of Citrasundarī, the wife of King Sahasrāra, Aśanivega’s son, an auspicious dream having been seen. In course of time she had a pregnancy-whim for union with Śakra, which was difficult to fulfill, difficult to tell, the cause of physical weakness. Questioned persistently, with difficulty she told her husband about her pregnancy-whim, her head bowed from shame. Sahasrāra assumed the form of Sahasrākṣa by a charm and, known by her as ‘Śakra,’ satisfied the whim. At the right time she bore a son, whose strength of arm was not deficient, who was named Indra because of the whim for union with Indra. When he was grown, endowed with knowledge of vidyās and with strength of arm, Sahasrāra gave him the kingdom and became absorbed in dharma himself.

He (Indra) conquered all the lords of the Vidyādharas and he began considering himself Indra because of his birth from the Indra-pregnancy-whim. He established four Dikpālas, seven armies and generals, three assemblies, the thunderbolt as his weapon, his elephant as Airāvaṇa, his courtesans as Rambhā, et cetera, his minister as Bṛhaspati, and the leader of his infantry with the same name as Naigameṣin. So he ruled his whole kingdom by Vidyādharas with the same names as the retinue of Indra with the idea, “I myself am Indra.” Mākaradhvaji, sprung from the womb of Ādityakirti, lord of Jyotiṣpura, became Soma, the regent of the east. The son of Varuṇā and Megharatha, a Vidyādhara, lord of Meghapura, became Varuṇa, the regent of the west. The son of Sūra and Kanakāvali, lord of Kāñcanapura, was called Kubera, the regent of the north. The son of Kālāgni and Śrīprabhā, lord of Kiṣkindhanagara, became Yama, regent of the south.

King Mālin could not endure Indra, the Indra of the Vidyādharas, priding himself on the thought, “I am Indra,” just as a rutting elephant can not tolerate another elephant. With brothers, ministers, and friends whose strength was unequaled, he set out for battle. For there is.no other charm of the powerful. Other heroes among the Rākṣasas, together with the Vānaras, advanced through the air with lions, elephants, horses, buffaloes, boars, bulls, et cetera, as vehicles. Crows, donkeys, jackals, and cranes cried out, with bad fortune as the fruit (of seeing them), even though they were on the right.[3] There were other unfavorable omens and bad signs and wise Sumālin tried to prevent Mālin from starting. Scorning his advice, Mālin, proud of his strength of arm, went to Mt. Vaitāḍhya and summoned Indra to battle. Indra went to the battlefield, mounted on Airāvaṇa, brandishing a thunderbolt in his hand, accompanied by his generals, Naigameṣin, et cetera, and by the regents, Soma and others, carrying various weapons, and by other Vidyādhara-soldiers. The soldiers of the Rākṣasa and Indra attacked each other, terrifying with missiles in the air, like clouds with lightning.

In some places chariots fell like mountain-peaks; in other places elephants fled like clouds scattered by the wind. Here soldiers’ heads fell, causing fear of Rāhu;[4] there horses, of whom one foot had been cut off, moved as if they were hobbled. Mālin’s army was divided by Indra’s army angrily. What can an elephant do, even though strong, when it has been caught by a lion? Then Mālin, the king of the Rākṣasas, followed by Sumālin and others like a forest-elephant by his herd, attacked with violence. He, lord of the wealth of heroism, attacked Indra’s army with clubs, hammers, and arrows, like a cloud with hail. Indra with his regents of the quarters, his army, and generals in full force, mounted on Airāvaṇa, hastened to action in battle. The soldiers began to fight, but Indra fought with Mālin, the regents and others with Sumālin and others. For a long time there was fighting between them, putting each other’s life in jeopardy. For generally life is like a straw to those who desire victory. Without any trickery in fighting Indra soon killed Mālin, who was crowned with heroism, with his thunderbolt, like a cloud killing a lizard with lightning. When Mālin was killed, the Rākṣasas and Vānaras were terrified and, commanded by Sumālin, went to the Laṅkā that is in Pātāla. Indra at once granted Laṅkā to Vaiśramaṇa, the son of Viśravas, sprung from Kauśikā’s womb, and went to his own city.

A son, Ratnaśravas, was borne by his wife, Prītimatī, to Sumālin who remained in the city Pātālalaṅkā. When he had grown up, one day Ratnaśravas went to a charming flower-garden for the purpose of acquiring vidyās. He remained there in a secret place, holding a rosary, muttering prayers, his gaze fixed on the end of his nose, as motionless as if painted. While he was standing thus, a certain Vidyādharī, a young maiden with an irreproachable form, stood near him at her father’s command. Then she said aloud to Ratnaśravas, “I am a mahāvidyā, by name Mānavasundarī, and have been won by you.” Ratnaśravas, by whom a vidyā had been won, dropped the rosary, looked at the Vidyādharī standing in front of him, and said to her: “Why have you come here? Whose daughter are you? Who are you?” She replied: “In Kautakamaṅgala, the home of many curiosities, there is a famous king of Vidyādharas, Vyomabindu. His elder daughter, Kauśikā, my sister, is married to King Viśravas, lord of Yakṣapura. She has a son, skilled in polity, named Vaiśramaṇa, who now rules in Laṅkā by order of Śakra. But I, Kaikasī, Kauśikā’s younger sister, have come here, given to you by my father in accordance with an astrologer’s prediction.” Sumālin’s son summoned his relatives and married her on the spot; founded the city of Puṣpāntaka, and remained there, amusing himself with her.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

His brother-in-law in Laṅkā.

[2]:

The sādhu recited the namaskāra so the monkey could hear it.

[3]:

With a play on ‘right’ and ‘left’ as ‘favorable’ and ‘un favorable.’

[4]:

Rāhu is depicted as a bodiless head.