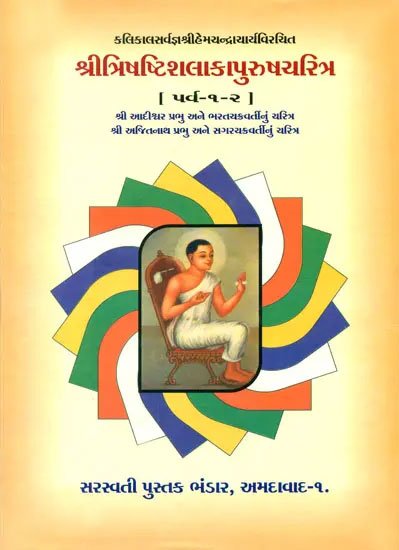

Trishashti Shalaka Purusha Caritra

by Helen M. Johnson | 1931 | 742,503 words

This page describes Story of Kanakashri which is the fifth part of chapter II of the English translation of the Shantinatha-caritra, contained within the “Trishashti Shalaka Purusha Caritra”: a massive Jain narrative relgious text composed by Hemacandra in the 12th century. Shantinatha in jainism is the sixteenth Tirthankara (Jina) and one of the 63 illustrious beings or worthy persons.

Part 5: Story of Kanakaśrī

When the king, chief of the prudent, had seen this dramatic art, he considered the two slave-girls to be jewels in the ocean of existence. Then the king entrusted his daughter, named Kanakaśrī, to the fictitious slave-girls for instruction in acting. When they had seen the maiden, who had reached youth, whose face was like a full moon, eyes like a frightened doe’s, lips like ripe bimbas, neck like a conch, arms like lotus-tendrils, breasts like golden pitchers, waist slender as the middle of a thunderbolt, navel deep as a tank, hips resembling a sandy beach, thighs like a young elephant’s, shanks like a doe’s, hands and feet like lotuses, whose body was immersed in the water of loveliness, endowed with sweet speech, whose body was soft as a śirīṣa, the fictitious slave-girls showed her again and again with gentle words and taught her thoroughly the dramatic art with modes of expression—all of it, including the catastrophe.[1]

In the midst of the drama the slave-girls sang at length praises of long-armed Anantavīrya, because of beauty, courage, et cetera. Kanakaśrī asked, “Who is this superior man about whom you sing constantly, girls?” The fictitious slave-girl, Aparājita, smiled and said: “Fair lady, in this province there is a large city, Śubhā. Its king was Stimitasāgara, an ocean of virtues, a sun in splendor. He, noble-minded, “had an elder son, the sole abode of good breeding, Aparājita, unconquered by his enemies. Anantavīrya was the younger son, but not inferior in spotless virtues, who surpasses Kandarpa in beauty, who splits the knot of insolence of his enemies. He, liberal, keeping his promises, considerate of those who have come for protection, his arms long as the king of serpents, his chest broad as a rock, like an abode of Śrī, like the supporting ground of the earth, the sun to the lotuses of followers, an Ocean of Milk of courtesy—how can he, noble, be described by us of little wit? There is no one among gods, asuras, and men who is his equal.”

When Kanakaśrī heard that, she was filled with waves of longing like a pond with waves blown up by the wind, just as if she saw him before her. She remained in thought, like one pierced in reality by the arrows of Smara in the guise of horripilation, motionless like a puppet.

“That kingdom is blessed, that city is blessed, those subjects are blessed, those women are blessed, of whom Anantavīrya is the leader. The moon, though far away, rejoices the night-blooming lotus with its rays; the cloud, though in the sky, makes the pea-hens dance. This has happened to them, indeed, from favorableness of fate. What fate will there be for Anantavīrya and me? How is he to be seeu, to say nothing of becoming my husband? Even a friend is hard to find to accomplish this desire.” Aparājita, expert in interpretation of feelings by gestures and facial expressions, observed that she had such thoughts and said to Kanakaśrī: “Why are you depressed? Why do you seem wounded, as it were, young maiden, when you have heard about Aparājita’s younger brother from my lips?”

Kanakaśrī, her face tearful, like a lotus with a mass of snow, very miserable, replied with words broken by hoarseness:

“The desire to seize the moon with the hand, to reach the sky with the feet, to cross the ocean with the arms, such, indeed, is my desire to see him. How can the lord of Śubhā, fortunate, be made to come within my range of vision by me, unfortunate? Alas! what a desire of mine!” The elder man-actress said: “Fair lady, if you wish to see him, then enough of depression, maiden. I shall show him to you. By the power of a magic art, I shall bring Anantavīrya and Aparājita here, like spring and the wind from Malaya to a forest.”

Kanakaśrī said: “Everything is possible for you, since you are an attendant of these two oceans of virtue. I think fate is favorable to me, since you so speak. Some family-divinity of mine surely descended into your mouth. Carry out your speech right now, you who know the arts. For even an attendant of such people surely does not lie.”

Then Aparājita and Anantavīrya, Beauty and Love, immediately assumed their own forms, delighted like gods. Aparājita said: “Fair lady, does my brother Anantavīrya agree with the description I gave just now, or not? His superiority in beauty, et cetera, has been described by me only to a small extent. He is not within the range of speech. Make him within the range of your vision.”

At the sight of him, the daughter of Damitāri was penetrated simultaneously by agitation, astonishment, shame, delight, rapture and unsteadiness. Considering herself at once the sister-in-law of Aparājita, the maiden made a veil from her upper garment. Anantavīrya’s body was rough from its hair on end, like a kadamba in flower, at the rising of a cloud in the form of Love. Then the gazelle-eyed maiden abandoned her inherent pride and bashfulness, took upon herself the role of go-between, and said to Anantavīrya:

“Mt. Vaitāḍhya on the one hand, and the city Śubhā on the other; the report on the acting of the slave-girls to my father by Nārada, the demand of the slave-girls, who were yours, by my father; the coming here of you two after assuming the form of the slave-girls, the entrusting of me to you for instruction in acting; the description of your virtues, husband, by your elder brother, the sudden revelation of yourselves by you two—all that which was inconceivable took place by the increase in my good fortune. Just as you were my teacher in drama, so you alone are my husband. Henceforth, if you do not protect me from Love, my death will be on your head. My heart has already been taken by you just by hearing about you. No w take my hand. Be gracious. Favor me. Surely even in existence, there was really no existence on my part because of the non-existence of a bridegroom like you among the young princes of the Vidyādhara-kings of the north and south rows of Mt. Vaitāḍhya. By good fortune you have been attained, a life-saving remedy, the only moon for the world of the living.”

Anantavīrya replied: “Fair-browed lady, if you so wish, rise. Certainly we shall go to the city, Śubhā, beautiful maiden.”

Kanakaśrī replied: “You are my husband. But my father, wicked, arrogant from his power over magic arts, will cause great evil. For he is an abode of evil. You two are alone, unarmed, though strong.”

Anantavīrya smiled and said: “Do not be afraid, timid girl. What is your father in battle with my noble brother, even with all his forces? Anyone else who, wishing to fight, follows, we will send to death. Be unafraid, my dear.”

Thus addressed by Anantavīrya, possessing strength of arm himself, Kanakaśrī set out like Śrī in person choosing her husband. Anantavīrya, with arms raised like a palace with flags, said in a very loud voice, deep as thunder:

“Sir captains of fortresses! Sir generals, ministers, princes, vassals, and soldiers, all of you! And all other adherents of Damitāri, be attentive! Hear my speech. I here, Anantavīrya, accompanied by Aparājita, am taking the daughter of Damitāri to my house. No censure is to be made, such as, ‘She has been taken secretly.’ Do not disregard this. Consider your own strength, carrying weapons.”

After he had made this proclamation, Anantavīrya with his wife and Aparājita set out through the air in an aerial car made by magic.

When Damitāri heard of that, saying, "Who is this miserable creature, belonging to earth, wishing to die?” he instructed his soldiers: “Quickly kill or capture this low person and his brother. Then bring back my daughter. Let evil conduct bear fruit in him.” So instructed by him, the soldiers, clearly of violent disposition, ran forward with weapons raised, like elephants with raised tusks. The divine jewels, the plough, bow, et cetera, then appeared to Aparājita and Anantavīrya. Many Damitāris, the soldiers of Damitāri, first attacked simultaneously with weapons, like clouds with streams of water. They trembled like deer at the effortless fighting of the two man-tigers undisturbed by anger. But when Damitāri heard that they were in flight, angered, he set out, making the sky look like a grove with high trees with his weapons.

"Villain, fight! fight!” “Stop! stop!” “Come! come!” "Hurl your weapon! hurl it!” "You shall die! You shall die!” “I will spare your life. Give up the master’s daughter.”

When Kanakaśrī heard these remarks, and similar ones, of the soldiers, which were terrifying from their great conceit and bitter to the ear, she became distressed, whispering, “Husband, husband.” Anantavīrya said to her: “Why are you needlessly terrified by your father’s noise in the air, which is like the croaking of a frog, foolish girl? Do you see Damitāri and his army being terrified or killed by me, like Maināka by Vajrin.”

After comforting Kanakaśrī in this way, Śārṅgadhara, like a lion that has been threatened, turned with Aparājita to battle. Damitāri’s soldiers, destroyers of enemies, surrounded Śārṅgin by the crore, like moths a light. Then Anantavīrya, a Meru in firmness, angry, created at once an army twice as large as his army by magic art. Damitāri’s soldiers began then to fight with it, their bodies wet with the mud of blood, like mountains with red-colored minerals.

“May he be my husband whose headless trunk dances.” “I am eager for him as a husband who advances threaded on a lance.” "When will he sport with me, who dyes (in blood) the one fighting with him?” “He is my husband who takes the lance which is entering his mouth in his teeth.” “He is my lord who mounts the elephant’s boss.” “I am the servant of him who fights with his helmet when his weapon is broken.” “He shall be my lover who is armed with an elephant’s tusk which has been pulled out.” Such passionate remarks were made by goddesses in the air.

Damitāri’s soldiers, arrogant from power over magic arts also, were not broken at all in battle, like bhadra-elephants.[2] Then Hari blew Pāñcajanya like an actor in the representation of a battle-play, which filled the space between heaven and earth with noise. Dazed by the sound of the conch of Viṣṇu, conqueror of the world, the enemy fell, foaming at the mouth like epilectics. Then King Damitāri himself mounted his chariot and fought with Anantavīrya with divine weapons and missiles. When he realized that Śārṅgin was hard to conquer, Kanakaśrī’s father recalled the cakra which was like a firm friend in time of need. Filled with hundreds of flames, it fell into Damitāri’s hand quickly, like a submarine fire in the ocean.

Damitāri said: “Villain, if you stay, you will die. Go at once. When you have released my daughter, you are released, scoundrel!”

Anantavīrya replied, “I shall go when I have taken your cakra and your life, as well as your daughter. Not before.”

Answered in this way, Damitāri, blazing with anger like a fire, whirled the cakra and hurled it at Aparājita’s brother. Hari fell, dazed by the blow from the hub of the cakra. Fanned by Aparājita, he soon got up, as if he had been asleep. That very cakra, remaining near, was taken by Śārṅgapāṇi. Though it had a hundred spokes, it seemed to have a thousand in his hand. The Ardhacakradhara smiled and said to the Pratyardhacakrin, “You are free, because you are Kanakaśrī’s father. Go now, sir!”

Damitāri said to him: “Why are you armed with my weapon, villain, like a rich debtor with the money of the creditor? Hurl the cakra! Hurl it! And hurl now your valor into the ocean of my strength, Anantavīrya, or turn into a clod.”

Anantavīrya, so addressed, resembling Antaka (Yama) angered, hurled the cakra, and cut off Damitāri’s head, like a lotus. The gods, delighted at his strength, rained five-colored flowers above Anantavīrya, and said:

“All you Vidyādhara-kings, listen attentively. Anantavīrya is Viṣṇu; and Aparājita is Bala. Approach his feet; turn from the field of battle with one whose rising is to be worshipped, like the moon, and like the sun.” Then all the Vidyādhara-kings went with bowed heads to Baladeva and Vāsudeva for asylum giving protection. Hari set out in a chariot for the capital, Śubhā, with the Vidyādhara-kings, his elder brother, and his wife. As Hari went near Mt. Kanaka, the Vidyādharas said to him:

“Do not show disrespect to the holy Arhats here. There are many shrines of the Jinas on Mt. Kanaka. After Your Honor has worshipped them properly, go from here.” Śārṅgabhṛt and his retinue got out of their chariots and worshipped the shrines which make the eyes cool. Looking at the mountain with curiosity, he saw Muni Kīrtidhara at one side engaged in pratimā with a fast extending over a year. Hari rejoiced because he saw him, whose omniscience arose just at that time from the destruction of the ghātikarmas and for whom a festival was held by the gods. After they had circumambulated him three times, had paid homage to him, and had sat down with folded hands, Hari and his retinue listened to a sermon by him.

At the end Kanakaśrī asked the muni, “Why did the killing of my father and separation from my relatives take place?” The muni related:

Previous incarnation of Kanakaśrī:

“There is a flourishing village, Śaṅkhapura, in east Bharata in the continent Dhātakīkhaṇḍa. A woman lived there, named Śrīdattā, afflicted with poverty, who earned a living by working in other people’s houses. She spent the whole day in threshing, grinding, carrying water, sweeping the house, smearing the house (with cow-dung), et cetera. She took her food after the whole day had passed. Verily, her lot was a miserable one, like the sight of an owl.

One day in her wandering she came to a mountain, Śrīparvata by name, which resembled the mountain of the gods (Meru) in beauty. There she saw a great muni, named Satyayaśas, seated on a crystal rock,[3] purified by the three controls, undefeated by trials hard to resist like ghouls, with the five kinds of carefulness unbroken, with an immeasurable wealth of penance, free from worldly interest, free from affection, tranquil, who regarded gold and a clod as the same, engaged in pure meditation, motionless as a mountain-peak. When she saw him like a kalpa-tree, delighted, she bowed to him. He gave her the blessing ‘Dharmalābha,’ a pregnancy-whim of the tree of emancipation.

Śrīdattā said to him: ‘Judging from such a miserable condition (as mine), I did not practice dharma at all in a former birth. To me constantly consumed by painful work like a mountain burned by summer heat, your speech “Dharmalābha” was like rain. Even if I, unfortunate, am not suitable for it, nevertheless this speech of yours is unerring. Give me some instruction for good fortune. Do something so that I shall not be so (ill-fated) again in another birth. With a protector like you, why should not the thing desired take place, protector?’

After hearing this speech of hers and considering the suitability, he instructed her to perform the penance called ‘dharmacakravāla.’[4] ‘You, absorbed in worship of gurus and Arhats, must perform two three-day (fasts) and thirty-seven caturthas. From the power of that penance another birth like this will not happen to you again, like offspring to a hen-crow.’[5]

She gave attention to his speech, bowed to the best of munis, went to her own village, and performed the penance. From its power she obtained sweet food when she broke her fast, such as she had never obtained before even in a dream, a prelude to the play of good fortune. From that time she received two and three times as much pay for her work in the houses of the rich and also good clothes. So Śrīdattā got to have a little money and made pūjā to the gods and gurus according to her ability.

One day an old place in the wall of her house, struck by wind, et cetera, fell down and she found gold, et cetera. At the completion of her penance she made a great finishing ceremony with pūjās in the shrines, gifts to monks and nuns, et cetera. On the fast-breaking day at the end of her penance, when she looked around the country, she saw the Ṛṣi Suvrata who had fasted for a month. Considering herself fortunate, she gave him herself pure food, et cetera, bowed to him, and asked about the religion of the Arhats. The muni replied to her: ‘It is not our rule for a sermon to be delivered anywhere by the ones who have gone for alms, lady. If you wish to hear religious instruction, come at the right time to my house when I have gone there, lady.’ With these words he went away.

People of the city and Śrīdattā went to pay homage to the muni who had broken his fast and was studying. After they had paid homage to him and had seated themselves in proper places, he delivered a sermon in a gracious voice.

Sermon:

‘A being, wandering through the eighty-four lacs of species of birth-nuclei in worldly existence, attains a human birth by chance, like a blind man reaching a desired place. The religion taught by the Omniscient, very difficult to obtain, is the foremost among all religious in it (saṃsāra), like the moon among heavenly bodies. So, efforts together with right-belief must be made for it alone by means of which a soul in worldly existence crosses the ocean of existence easily.’

Śrīdattā bowed at Suvrata’s feet and accepted the religion taught by the Omniscient together with right-belief. After they had paid homage to Muni Suvrata all the people of the city and Śrīdattā, delighted, went to their own houses. For some time she practiced that religion; then a doubt arose in her mind from the development of her karma. ‘I do not know whether or not I shall obtain the fruit which is said to be the highest fruit of the religion of the Jinas.’ Because Śrīdattā felt such a doubt even with the instruction of such a guru, then the inevitable consequences were hard to prevent.

One day when she had started out to pay homage to Satyayaśas, she saw a pair of Vidyādharas in an aerial car in the sky. Confused by their beauty she went to her own house and died without confessing or repenting the doubt.

Now there is a mountain, Vaitāḍhya, in the province Ramaṇīya which is the ornament of East Videha in this very Jambūdvīpa. On it there is a city, Śivamandira, the abode of happiness, which is like a twin of Śakra’s city. Its king was named Kanakapūjya, whose feet were worshipped by powerful Vidyādhara-kings. I was the son, Kīrtidhara, of his wife Vāyuvegā. My wife was named Anilavegā, the head of my harem. Once upon a time she saw three dreams while she was asleep in the night. An elephant as white as Kailāsa, a fine bull roaring like a cloud, a pitcher which resembled a treasure-pitcher—these were the three dreams in succession. At the end of the night the chief-queen, whose face was blooming then like a lotus, related these dreams to me. I said, ‘You will have a son who will be master of a three-part territory, with half the power of a Cakravartin.’

At the proper time the queen bore a son, who resembled a god, complete with all favourable marks, like a mine bearing a jewel. Because I had been especially victorious over my enemies while he was in the womb, I named him Damitāri. Gradually he grew up and gradually he absorbed the arts, and gradually he attained youth purified by beauty.

One day the Lord, the Jina, causing tranquillity, the noble-minded Śānti,[6] wandering to another place in the province, victorious, stopped in a samavasaraṇa. After I had paid homage to him, I sat down and listened to a sermon. I became disgusted with existence at once and established Damitāri in the kingdom. Then I adopted mendicancy at Śrī Śānti’s feet and at that time undertook two kinds of discipline, grahaṇa and āsevanā.[7] I performed pratimā for a year on the mountain here and just now omniscience arose from the destruction of the ghātikarmas. Damitāri became a king, a powerful Prativiṣṇu, to whom the cakra had appeared, who had conquered the three-part territory. The soul of Śrīdattā became you, his daughter Kanakaśrī, by Damitāri’s wife Madirā. Because she died without confessing and repenting her doubt, you have experienced this separation from relatives and the killing of your father because of that sin. Verily, a stain on religion, even though small, causes endless pain. Even a little poison, which has been swallowed, is sufficient to destroy life. You must not act so again that such a thing will happen again, but right-belief free of the five faults[8] must be adopted.”

Then Kanakaśrī, at once feeling quick disgust with existence, declared to Cakradhārin and Lāṅgaladhārin:

“If such misfortune is experienced because of even a little sin, enough for me of the pleasures of love, mines for the production of sin. Just as a boat sinks in water from even a small crack, so a person sinks in misfortunes from even a small sin. At that time when I was timid from poverty and was practicing such penance, for some reason there was doubt. Alas for my wretched fate! Now that I have obtained power and am enjoying pleasures, of what importance is a mere doubt since there may be other faults? So be gracious and consent to my taking the vow. I am afraid of this Rākṣasa of existence devoted to such trickery.”

With eyes wide-open in astonishment, they said: “From the guru’s favor this may take place without hindrance. However, let us go now to the city Śubhā, very intelligent lady, that we may make your departure-festival with great magnificence. You should take the vow, which resembles a boat for crossing the ocean of existence, there before the Jina Svayamprabha, sinless lady.”

She agreed and after bowing with devotion to the sage they took her and went to the city Śubhā. In front of it they saw the son Anantasena fighting with men sent for battle by Damitāri. When Sīrin saw Anantavīrya’s son surrounded by them like a boar by dogs, whirling his plow, he ran forward angrily. Damitāri’s soldiers ran away in all directions, unable to withstand Bala, like balls of cotton unable to withstand a wind. Janārdana and his retinue entered his city; and was installed by kings as ardhacakrin on an auspicious day.

The Jina Svayamprabha came there one day, as he wandered over the earth, and stopped in a samavasaraṇa. Then the door-keepers said to Anantavīrya, “Today you are very fortunate because of the coming of Svayamprabhanātha.” He gave them twelve and a half crores of silver and with his elder brother and Kanakaśrī went to pay homage to the Master. The Blessed Svayamprabha, from a desire to benefit persons capable of emancipation, delivered a sermon in speech conforming to all dialects.

Kanakaśrī said, “After taking leave of Śārṅgin at home, I shall come for initiation. Be compassionate, Teacher of the World.” The Tīrthakṛt said, “Negligence must not be shown”; and Kanakaśrī, Hari, and Sīrin went to their house. She took leave of Hari and, after he had held the departure-ceremony with great magnificence, she went there and adopted mendicancy under the Lord. She performed penance—the ekāvali, muktāvali, kanakāvali, bhadra, sarvatobhadra, et cetera. (see notes on penances) One day when the fuel of the ghātikarmas had been consumed by the fire of pure meditation, her spotless omniscience arose. After she had gradually destroyed the karmas prolonging life (bhavopagrahin), Kanakaśrī reached the place which has no rebirth.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

See I, n. 235.

[2]:

See I, n. 128.

[3]:

[4]:

The penance starts with a three-day fast, then a fastbreaking day, then 37 fasts of one-day alternating with fast-breaking days, then a three-day fast and a fast-breaking day, making a total of 82 days for the series. Tapāvalī, p. 5.

[5]:

Cf. kākavandhyā, ‘a woman that bears only one child.’ I have found nothing to support the belief that a hen-crow lays eggs only once.

[6]:

Of course, not our Śāntinātha, but one in Videha in a past period.

[7]:

Grahaṇaśikṣā is the study of the sūtras, the acquisition of knowledge of religious practices; āsevanāśikṣā is the practice of them. See the Rājendra, s.v. sikkhā, and the Dharmaratnaprakaraṇa 36.

[8]:

See I, n. 119.