Matangalila and Hastyayurveda (study)

by Chandrima Das | 2021 | 98,676 words

This page relates ‘Gaja-pitha or Gaja-prishtha (elephant-platform)’ of the study on the Matangalina and Hastyayurveda in the light of available epigraphic data on elephants in ancient India. Both the Matanga-Lila (by Nilakantha) and and the Hasti-Ayurveda (by Palakapya) represent technical Sanskrit works deal with the treatment of elephants. This thesis deals with their natural abode, capturing techniques, myths and metaphors, and other text related to elephants reflected from a historical and chronological cultural framework.

Gaja-piṭha or Gaja-pṛṣṭha (elephant-platform)

As we come to know from the above discussion and according to Purāṇas elephants are “Diggajas” or the guardian of cardinal points of the universe. The Purāṇas also reveal the knowledge of the cardinal points and related them to various phenomena. The designation of directions in the Purāṇas and later literature like Saptapadārthī[1] is significant in the sense that it assigns each direction to each God. These are as follows[2] :

[Table 1: Different Directions and Their Presiding Deities]

| Sl. No. | Directions | Presiding deities |

| 1. | Pūrva (east) | Indra |

| 2. | Āgneya (south-east) | Agni |

| 3. | Dakṣiṇa (south) | Yama |

| 4. | Naiṛtya (south-west) | Niṛti |

| 5. | Paścima (west) | Varuṇa |

| 6. | Vāyavya (north-west) | Marut |

| 7. | Uttara (north) | Kubera |

| 8. | Īśāna (north-east) | Īśa |

| 9. | Ūrdhva (zenith) | Brahmā |

| 10. | Adhaḥ (nadir) | Śeṣanāga |

It is also noticeable that Niṛti and Śūrya (used for denoting south-west) were inter-changeable and so were Īśa and Pṛthivī or Śiva denoting north-east.[3]

We already discussed the name of Aṣṭadiggajas–Airāvata, Puṇḍarika, Vāmana, Kumuda, Añjana, Puṣpadanta, Sārvabhauma, Supratīka respectively.

Eight elephants of cardinal points were so famous that they have been used as chronograms of the portion of the inscriptions indicating the number eight. Piṭhāpuram inscription of Pṛthvīśvara of Śaka year 1108[4], Bitrakugunta grant of Saṃgam II of Śaka year 1278[5] and many other epigraphic records of different dynasties used elephants with number eight to measure Śaka year in chronograms. Epigraphic records often mention the diggajas as metaphorical phrase. Khairā Plates of Yaśaḥkarṇḍeva of Kalacurī samvat 823 records that the king erected high pillars of victory near the ends of the earth as companions of the posts to which the elephants of the quarters are fastened and the king’s glory was bright like the tusks of the elephants (Airāvata) of the king of heaven (Indra)[6]. Resembling liberality diggajas have been seen in Rādhanpur Plates of Govinda III, Śakasaṃvat 730[7]. The record states “seeing that his liberality exceeded the liberality of others, while their own practice of liberality lagged behind that of Karṇa [i.e. while the stream of their rutting juice flowed beneath their ears (Karṇa)]” (v. 5). Scholars opine that the adjective ending with–“Saṃtatibhṛtaḥ” can only be taken to qualify diggaja, who utterly abashed as it were, hosted themselves at the confines of the quarters.

Our cultural heritage also renders the scenes from Purāṇic and mythical descriptions of elephants. As the mythical diggajas support the universe, so elephants in sculpture lend themselves to a feature in sacred architecture known as the gaja-piṭha or pṛṣṭha (elephant-platform). This may occupy either the ādhiṣṭhāna (base) or upapiṭha (sub-base or plinth) of a shrine or temple, and consist of a range of elephants” foreparts, standing in repose or charging outwards towards the viewer. The symbolism not only alludes to the mythical caryatides of the universe, but also makes a more direct reference to the proverbial strength of elephants–best suited to “supporting” the dwellings of gods upon their shoulders.

Besides this one finds rows elephants depicted in varied forms and features and their activities detailed in the vedibandha of the temples which are known as gajatharas or gajastaras. It is not imperative, however, that all temples possess a “gajapiṭha”. A quite different feature, also optional, is the “gaja-thara” (elephant-course): a horizontal frieze of elephants, generally in the lower most register of sculptures in the ādisthāna. Unlike the conventionalized foreparts of the gaja-piṭha elephants, gaja-thara elephants may be rendered in profile-marching in procession or in war and hunt scenes[8].

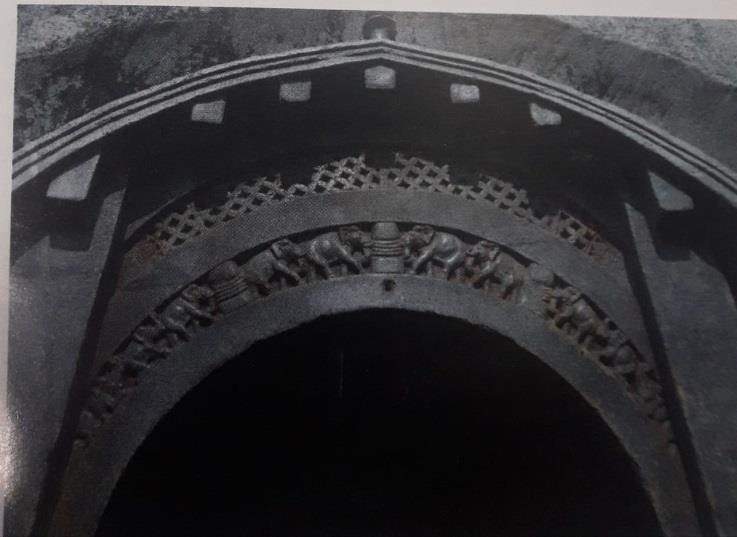

The scale and styling of a gaja-piṭha can range from the modest to the monumental. The earliest use of gajapiṭha as an architectural element is seen in the Barabar caves where the roof is barrel vaulted i.e. gaja-pṛṣṭhakara. This can be dated to the 3rd century BCE without an iota of doubt. The animals too many appear as shallow relief carving or as bolder.

[13. Gaja-piṭha, Lomash Rishi Cave, Barabar hill. Courtesy: Susmita Basu Majumdar]

Two different interpretations are presented in two early Cālukya temples in the Deccan. In the Badami example, seemingly random arrangement of elephant’s foreparts protrudes from the sides of a high upapiṭha, while a pair of sculptured lions guards the entrance stairway. In the adhiṣṭhāna of the Pattadakkal temple a moulding of rampant elephants is loosely interspersed with the foreparts of lions. In a typical example of the exuberant Hoysala style, the stellated upa-piṭha of the Keśava temple I Somnāthpur has a set of richly decorated elephant radiating at ground level from the sides of the plinth. Some of the sculptures support rainspouts on their heads. In the Adhiṣṭhāna of the temple proper the gaja-thara presents a finely worked procession of war elephants.[9]

[14a. Gajathara image from an early medieval Śiva temple of Malhar. Courtesy: Susmita Basu Majumdar]

[14b. Close up of Gajathara image. Courtesy: Susmita Basu Majumdar]

Footnotes and references:

[2]:

[3]:

[4]:

EI, Vol. IV, pp. 32-54.

[5]:

Ibid., Vol. III, pp.32-33.

[6]:

Ibid., Vol. XII, v.19,22, p.216.

[7]:

Ibid., Vol. VI, pp. 243, 247-248.

[8]:

V. Ram. Elephant Kingdom–Sculptures from Indian Architecture, p.23.