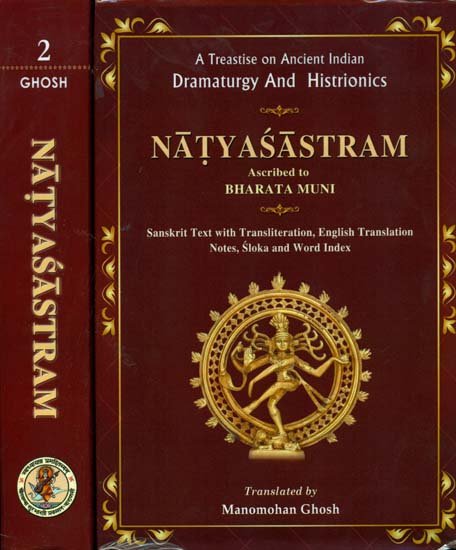

Natyashastra (English)

by Bharata-muni | 1951 | 240,273 words | ISBN-13: 9789385005831

The English translation of the Natyashastra, a Sanskrit work on drama, performing arts, theater, dance, music and various other topics. The word natyashastra also refers to a global category of literature encompassing this ancient Indian tradition of dramatic performance. The authorship of this work dates back to as far as at least the 1st millenn...

Chapter XXIX - On Stringed Instruments (tata)

Application of Jātis to Sentiments

1. The Ṣaḍjodīcyavatī and the Ṣaḍjamadhyā should be applied in the Erotic and the Comic Sentiments respectively because Madhyama and Pañcama[1] are amplified in them.[2]

2. The Ṣāḍjī and the Ārṣabhī should be applied in the Heroic, the Furious and the Marvellous Sentiments after making [respectively] Ṣaḍja and Ṛṣabha their Graha note[3].

3. The Naiṣādī with (lit. (in) Niṣāda as its Arnśa note, and the Ṣaḍjakaiśikī with (lit. in) Gāndhāra (as its Aṃśa note] should be the Jāti sung (lit. made) by expert singers[4] in the Pathetic Sentiment..

4. The Dhaivatī[5] with (lit. in) Dhaivata as its Aṃśa note [is to be applied] in the Odious and the Terrible [Sentiments]. [Besides this] the Dhaivatī is applicable in the Pathetic Sentiment[6], and [similarly] the Ṣaḍjamadhyā is to be applied in connection with madness.

5. The Jātis should be made in the application of Dhruvās by the producers, after [very carefully] considering the Sentiments, the action and the States [in a play].

6. These are the Jātis of the Ṣaḍja Grāma known to the wise. I shall now speak of the Jātis of the Madhyama Grāma.

7. The Gāndhārī and the Raktagāndharī, when they have Gāndhāra[7] and Niṣāda as their Aṃśa notes, should be applied in the Pathetic Sentiment.

8-9. In the Erotic and the Comic Sentiments, the Madhyama, the Pañcamī, the Nandayantī, the Gāndhārī, the Pañcamī and the Madhyamodīcyavā Jātis with Madhyama[8] and Pañcama amplified, should he applied.

9-10. In the Heroic, the Furious and the Marvellous Sentiments, the Karmāravī, the Āndhrī and the Gāndhārodīcyavā, with Ṣaḍja and Ṛṣabha as their Aṃśa notes, should be applied. And in the Odious and the Furious Sentiments the Kaiśikī with Dhaivata as their Aṃśa note, should be applied.

11. Only the Ṣaḍjamadhyā is the Jāti which can accommodate all the Sentiments. All notes [of the Grāma] may be its Aṃśa and these have been dealt with in the rules of [dramatic] production.

12. When a note [representing a particular Sentiment] is prominent (lit. strong) in a Jāti, the producers, in regard to the production of such a Sentiment should combine the song with it, i.e., should give it prominence there.

13-14. [For example,] a song in the Erotic and the Comic Sentiments should abound in many Madhyamas and Pañcamas (i.e., should be Jātis containing these notes in profusion), and in the Heroic, the Furious and the Marvellous Sentiments, songs should be made with many Ṣaḍjas and Ṛṣabhas. And the song in the Pathetic Sentiment should be full of many Gāndhāras and Niṣādas (lit. the seventh). Similarly a song in the Odious and the Terrible Sentiments should have many Dhaivatas.

15. In all the Aṃśās, these notes are to be applied according to rules with the suitable Kākalī and Antara-svara, and are to be made specially strong.

16. These Jātis relating to the dramatic performance, should be known by the wise. Now, listen about the notes prescribed in the instrumental music.

16ka-kha. The notes Madhyama and Pañcama are to be produced in the Comic and the Erotic Sentiments, Ṣaḍja and Ṛṣabha in the Heroic, the Furious and the Marvellous Sentiments, Gāndhāra and Niṣāda in the Pathetic Sentiment, and Dhaivata is to be produced in the Odious and the Terrible Sentiments. I shall speak after this on the characteristics of the Varṇas[9] and the Alaṃkāras[10].

The four Varṇas

17-18. The Varṇas[11] on which the Alaṃkāras[12] depend are of four kinds, viz. ‘Ascending’ (ārohin)[13] ‘Descending’ (avarohin)[14] ‘Monotonic’ (sthāyin, lit. staying)[15] and ‘Mixed’ (saṃcārin, lit. moving together)[16].

18-19. The Varṇa in which the notes go up [in the scale], is called Ascending[17] and in which they go down [in the scale], is called Descending[18]. The Monotonic Varṇa is that in which notes are the same and are equal [in pitch][19], and when the various notes come together they constitute what is called a Mixed Varṇa.[20]

20. These four Varṇas having [clearly] defined aspects, are taken (lit. born of) from the human (lit. physical) voice and they relate to the quality of the three voice registers (sthāna).

21. When a regular (lit. having a characteristic) song (pada) adds [at least] two Varṇas to it, then the Varṇas[21] give rise to Sentiments.

22. These four Varṇas are to be known as applicable to songs. Now listen properly about the Alaṃkāras which depend on them.

The Thirty-three Alaṃkāras

23-28. The Alaṃkāras[22] are: Prasannādi, Prasannānta, Prasannādyanta, Prasannamadhya, Sama, Bindu, Veṇu, Nivṛtta-pravṛtta[23], Kampita, Kuhara, Recita, Preṅkholitaka, Mandratāraprasanna, Tāramandraprasanna, Prasvāra, Prasāda Udvāhita, Avalokita, [Krama,] Niṣkujita, Udgīta, Hrādamāna, Rañjita, Āvarta, Parivartaka, Udghaṭṭita, Ākṣipta, Sampradāna, Hasita, Huṃkāra, Sandhipracchādana, Vidhūna[24], and Gātravarṇa.

The Monotonic Alaṃkāras

29-30. The Monotonic Alaṃkāras[25] are: Prasannādi, Prasannānta, Prasannādyanta, Prasannamadbya, Sama[26], Recita, Prasvāra[27] and Prasāda. Listen again, about the Alaṃkāras depending on the Mixed Varnas.

The Mixed Alaṃkāras

31-32. Mandratāraprasanna, Bindu, Preṅkholita, Nivṛttapravṛtta, Recita, Kampita, Sama, Kuhara, Veṇu, Rañjita, Avalokita, Āvartaka and Parivartaka are of the mixed class[28].

The Ascending Alaṃkāras

33-34. The Ascending Alaṃkāras[29] are: Niṣkūjita, Huṃkāra, Hasita, Bindu, Recita, Preṅkholita, Ākṣipta, Vidhūna, Udghaṭṭita, Hrādamāna, Sampradāna, Sandhipracchādana, Prasannādi and Prasannānta.

The Descending Alaṃkāras

35.[30] The Descending Alaṃkāras’ are Vidhūna, Gātravarṇa, Udvāhita, Udgīta and Veṇu.

36. These Alaṃkāras attached to songs of seven[31] forms, should be known to the wise. These [however] are not generally used (lit. desired) in the Dhruvās[32], because of their giving prominence to the Varṇas of Jātis [which are not used there].

37. Alaṃkāras, such as Bindu and Veṇu, are not to be used in their own measure (pramāṇa) while they are applied in the Dhruvās.

38-39. For the Dhruvā conforming to the meaning of the play, is to suggest its meaning, while the Varṇas (i.e., Varṇālaṃkāra) are to soften to (lit. weaken) the pada[33]. Now listen about the Varṇas which are [commonly] used.

39-43. [The Alaṃkāras] such as Prasannādi, Prasannānta, Prasannādyanta, Prasannamadhya, Bindu, Kampita, Recita, Tāra, Tāramandra, Tāratarā, Preṅkholita, Mandra, Mandratāra, Sama, Nivṛttapravṛtta, Prasāda, Apāṅga, Avaloka and Veṇu, belong to all the Varṇas[34], and all the Varṇas except the Monotonic ones, have their use [in songs][35]. Next I shall describe the characteristic[36] of the Alaṃkāras arising from the Varṇas.

The Definition of the Alaṃkāras

Prasannādi[37]—that in which a note rises (lit. becomes brilliant) gradually [from the low pitch].

44. Prasannāntā[38] this (Prasannādi) enunciated in the reverse order.

Prasannādyanta[39]—that in which the beginning and the ending notes are in a low pitch [and the middle one is in high pitch].

45. Prasannamadhya[40]—when note in the middle is of low pitch [but notes in the beginning and in the end are in high pitch].

Sama[41]—that in which a note repeats itself in the same pitch and is equal in all [parts],

46. Bindu[42]—when a note of one Kalā of low pitch after touching high pitch comes back [to its original pitch].

Nivṛttapravṛtta[43]—[when a note of one Kalā of high pitch], after touching low pitch comes back to its original pitch.

47. Veṇu[44]—that in which the tempo (laya) is playlike.

Kuhara[45]—that in which notes (lit the wind) being in the medium pitch (lit. stopped in the vocal passage) are (in a play-like tempo).

48. Recita[46]—trembling notes of three Kalās in high pitch (lit. in the head).

Kampita[47]—trembling notes of three Kalās in low pitch (lit. in the breast).

49-50. Preṅkholita[48]—that in which the notes ascending and descending occur [in each Kalā].

Tāra—a note of medium pitch (lit. in the throat)[49].

Mandra—a note of low pitch (lit. in the breast)[50].

50-51-Tāratar—a note of high pitch (lit. in the head)[51].

Tāramandraprasanna[52]—when (in a Kalā the fourth or the fifth note gradually falls (lit. assumes low gait) from a high pitch.

51-52. Mandratāraprasanna[53]—when in [a Kalā of] four or five notes they gradually rise to a high pitch from a low one after skipping over other low notes.

Prasvāra[54]—when [in a Kalā], a note ascend gradually by one note.

53. Prasāda[55]—when in a Kalā, notes descend gradually by one note.

Apāṅgika[56]—when in a Kalā, notes come together (i.e., once ascend and once descend).

54. Udvāhita[57]—when in a Kalā two consecutive notes ascend, and two such Kalās make one unit.

55. Avalokita (-loka)[58]—when in the Udvāhita the repeated Kalās are in the descending scale.

Krama[59]—when successive Kalās include one two, three; four, five, six, seven consecutive notes which ascend.

56. Niṣkūjita[60]—containing Kalās in which notes after ascending to the note following the one next to it, comes back to it.

57. Udgīta[61]—Kalās in the Prasvāra once (lit. in the beginning) ascending and next (lit. in the end) descending.

58. Hrādamāna[62]—notes in this order (i.e., as in the Udgīta) in two Kalās consisting of at least two or at most six-notes, where alternate notes come together.

59. Rañjita[63]—after staying in two consecutive notes of two Kalās, it ascends half a Kalā and then again descends to the preceding note.

60-61. Āvartaka[64]—eight Kalās of four consecutive notes ascending and descending. It is also formed with two alternative notes. In that case four Kalās will have ascending and descending notes.

62. Parivartaka[65]—eight Kalās in which a note ascends to the third one from it and skips over the next one to ascend in the note following, and descends in the same manner [in the next Kalā].

63. Udghaṭṭita[66]—containing [eighteen] Kalās which ascend for two notes and then leaving out the next note ascend to the following one.

64. Ākṣiptaka[67]—containing six Kalās of three notes.

65. Sampradāna[68]—as in the Ākṣipta, constituted with Kalās of four notes, [alternating with] Kalās [of three] notes in which, alternate notes are included.

66. Hasita[69]—constituted with double Kalās of two consecutive notes like laughter, as in the Ākṣipta.

67. Huṃkāra[70]—ascending as in the Hasita, at least two or at most four notes in each Kalā

68. Sandhipracchādana[71]—having groups of four Kalās with notes ascending from the beginning (lit. place) to high note and ascending from it to the original one and there being no throwing up.

69. Vidhūna[72]—after producing first the pada (song) containing two short notes, two consecutive notes will ascend in each Kalā.

70-71. Gātravarṇa[73]—as in the Huṃkāra notes ascend consecutively in the alternate Kalās [of four notes] in which the first two are trembling and the next two are of low pitch.

71-72 E and O as well as the other long vowels[74] are to be added [to notes in Alaṃkāras]. This is the properly given rule of the Karaṇas[75] of the Alaṃkāras in songs. Songs should be decorated with these Alaṃkāras without [coming in] conflict with [the rule concerning] the Varṇas.[76]

73. Alaṃkāras should be attached to proper places for example, the girdle (kāñcī)[77] should not be placed (lit. fastened over the breast. And too many Alaṃkāras without any song (varṇa) should not be used.

74. These are the Alaṃkāras depending on the Varṇas. Now I shall speak of those depending on rhythm (chandas) and [the quality of] the syllables (akṣara).

75. A song-without any Alaṃkāra will be like a night without the moon, a river without water, a creeper without a flower and a woman without any ornament.[78]

76. These are the thirty-three Alaṃkāras I spoke of, I shall now mention the characteristics of the Gītis.[79]

Alaṃkāras depending on the Gīti

77. Gītis are of four kinds: the first is Māgadhī, the second Ardhamāgadhī, the third Sambhāvitā and the fourth Pṛthulā.[80]

78. The Māgadhī is sung in different tempos (vṛtti).[81]

The Ardhamāgadhī changes (lit. revises) its tempo after half-time.

79. The Sambhāvitā is known to be constituted with long syllables and the Pṛthulā with short syllables.

80-81. These Gītis are known to be without any connexion with the Dhruvās.[82] But they are always to be applied by the musicians in the Gāndharva[83] only. I have spoken properly of the Gitīs. Now listen about the Dhātus.[84]

I shall now speak of the playing of the Dhātus.

Dhātus in playing stringed instruments

82. Four Dhātus[85] depending on the playing [of stringed] instruments[86] are: Vistāra (expansion), Karaṇa (production), Ābiddha (breaking up) and Vyañjana (indication).

The Vistāra Dhātus

83. The Vistāra includes four kinds of strokes: Saṃghātaja (growing out of contrast), Samavāyaja (growing out of combination), Vistāraja (growing out of amplitude) and Anubandhaja (growing out of mere succession).

84-85. Its (i.e. of the Vistāra) rules have been mentioned first as follows: [the Vistāra is of one stroke;][87] the Saṃghātaja and the Samavāyaja consist respectively of two and three [strokes]. The first is of four kinds, and the second of eight kinds. According, to the special ways of their production they have different rules.

86-87. [Notes are] known to be of low and of high pitch as they come out [respectively] of low (=mild) or high (=strong) [strokes]. This is the rule of striking that the players of stringed instruments[88] should know.

The Saṃghātaja strokes have the following varieties: two high, two low, low-high and high-low.

88-89. The Samavāyaja strokes have the following varieties: three high; three low; two low, one high; two high, one low; one high, two low; one low, two high; one low, one high, one low; and one high, one low, one high.

90. The Anubandha [-kṛta] due to [its formation by] breaking up, and combining [of the groups of strokes described before,] is irregular. These are always the fourteen kinds of the Vistāra Dhātus.

The Karaṇa Dhātus

91. In the playing of the Viṇā the five kinds of the Karaṇa Dhātu are: Ribhita, Uccaya, Nīraṭita, Hrāda and Anubandha.

92. The Karaṇa Dhātus will consist respectively of three, five, seven and nine [light] strokes, and the being combined[89] and all ending in a heavy [stroke].

The Ābiddha Dhātus

93. The Ābiddha Dhātu is of five kinds: Kṣepa, Pluta, Atipāta, Atikīrṇa and Anubandha.

94. The Ābiddha Dhātus will consist respectively of two, three, four and nine strokes made gradually and slowly, and a combination of these.[90]

The Vyañjana Dhātus

95-100. The Vyañjana Dhātu in playing the Viṇā, is of ten kinds. They are: Kala, Tala, Niṣkoṭita, Unmṛṣṭa, Repha, Avamṛṣṭa, Puṣpa, Anusvanita, Bindu and Anubandha.

Kala—touching a string simultaneously with the two thumbs.

Tala—striking a string with the left thumb after pressing it with the right one.

Niṣkoṭita—striking with the left[91] thumb only.

Unmṛṣṭa—striking with the left[92] fore-finger (pradeśinī)

Repha—one single stroke with all the figures of a hand.

Avamṛṣṭa—three strokes low down [in the string] with the little finger and the thumb of the right hand.

Puṣpa—one stroke with the little finger and the thumb.

Anusvanita—the stroke being lower [in the string than] in the Tala [described above].

Bindu—one heavy stroke in a single string.

101. Anubandha—one irregular combination[93] (lit. breaking up and combination) of all these and it relates to all the Dhātus.

These are the ten Vyañjana Dhātus to be applied to the Vīṇā.

102. These are the four Dhātus with their characteristics, which relate to the three Vṛttis[94] on which the playing of [stringed] instruments depends.

The three Vṛttis

Styles of Procedure (gati-vṛtti) to be principally reckoned are three: Citra (variegated), Vṛtti (movement, i.e. having a simple movement) and Dakṣiṇa (dexterous). Instrumental music, time-measure (tāla)[95] tempo (laya)[96], Gīti (rhythm)[97], Yati[98] and Graha-mārga (way of beginning)[99] will determine their respective characters. [For example], in the Citra, [the Māgadhī is the Gīti], the instrumental music is concise (i.e. not elaborate), [the unit of] time-measure [is one Kalā], tempo is quick, and Yati is level (samā)[100] and the Anāgata Grahas preponderate. Similarly in the Vṛtti [the Sambhāvitā] is the Gīti, the instrumental music is * *, [the unit of] time-measure is two Kalās, the tempo is medium (madhya), the Yati is Srotogatā[101], and the Sama Graha-mārgas are preponderant. In the Dakṣiṇa, the Gīti is [Pṛthulā,] the unit of time-measure is of four Kalās, the tempo is slow (vilambita), the Yati is Gopucchā[102] and the Atīta Graha-mārgas are preponderant.

103. Names of the three Styles of Procedure (vṛtti) are Citra, Dakṣiṇa and Vṛtti. They give quality to the instrumental music as well as to the song, and have been defined in due order.

104. The Lalita[103] etc, the Jātis[104] of all these Styles of Procedure (vṛtti), when combined in the Dhātus, will become richer in quality.

The Jātis

105. And from a combination of the Dhātus, come forth the Jātis such as, Udātta, Lalita, Ribhita and Ghana.

106. The Udātta relates to the Vistāra Dhātus or to many other things.

The Lalita relates to the Vyañjana Dhātus and is so called because of its gracefulness.

107. The Ribhita relates to the Ābiddha Dhātus and is characterised by multitude of strokes.

The Ghana relates to the Karaṇa Dhātus and depends on their quantity (lit. aggregate of long and short notes).

Three kinds of music of the Vīṇā

108. The experts are to produce three kinds of music from the Vīṇā. They are Tattva, Anugata, and Ogha which combine [in them] many Karaṇas.

109. The music which expresses [properly] the tempo, time-measure, Varṇa, pada, Yati, and syllables of the song, is called the Tattva.

And the instrumental music which follows the song, is called the Anugata.

110. The Ogha is the music which abounds in the Ābiddha Karaṇas, has the Uparipāṇi Graha-mārga, quick tempo and does not care for the meaning of the song.

111. The rule in the playing of musical instruments, is that the Tattva is to be applied in a slow tempo, the Anugata in a medium tempo, and the Ogha in a quick tempo.

112. The experts in observing tempo and time-measure, should apply the Tattva in the first song [to be sound during a performance], and the Anugata in the second, and the Ogha in the third one.

113. These are the Dhātus in the music of the Vīṇā, to be known by the experts. I shall now explain the Karaṇas included in the rules of playing the Vipañcī.[105]

The Karaṇas of the Vipañcī

114. The Karaṇas[106] [in playing the Vipañcī] are Rūpa, Kṛtapratikṛta, Pratibheda, Rūpaśeṣa, Ogha and Pratiśuṣka.

115. When on the Vīṇā, two heavy and two light syllables are played, it is the Rūpa.[107]

And this Rūpa performed in the Pratibheda it is the Kṛtapratikṛta.[108]

116. When two different Karaṇas are side by side played on the Vīṇā, and heavy and light syllables are shown, it is called the Pratibheda.[109]

Continuing [the music] in another Vīṇā, when the [principal] Vīṇā has stopped, is called the Rūpaśeṣa.[110]

117. The Ogha[111] includes the Ābiddha Karaṇas performed in the Uparipāṇi Graha-mārga.

The Pratiśuṣka[112] is the Karaṇa which is played by means of one string [only].

118. During the application of the Dhruvās, the experts should generally play with the plectrum (koṇa) two Vīṇās to accompany a song or other instruments.

119. Whether it be a place or a character, one should equally reflect it together with the song on the strings, and in the Vipañcī it will be something like the Karaṇa called the Ogha.

120. The Citra[113] is [a Vīṇā] with seven strings, and the Vipañcī[114] is that with nine strings. And the latter (Vipañcī) is to be played with the plectrum, and the Citrā with the fingers only.

121. The experts are thus to know of the Vipañcī which includes many Karaṇas. I shall next explain the Bahir-gītas which have [their fixed] characteristics.

122-124. Āśrāvaṇā,[115] Ārambha[116], Vaktrapāṇi,[117] Saṃghoṭanā[118], Parighaṭṭanā[119], Mārgāsārita[120], Līlākṛta[121], and the three kinds[122] of Āsāritas are the Bahir-gītas[123] to be applied first [in a play] by the producers, and [all] these should be applied without Tālas or with Tālas, and in the Styles of Procedure called the Citra and the Vṛtti.

125. The need for all these has already been mentioned by me in the rules for the Preliminaries[124]. I shall [now] describe their characteristics together with examples.

Tha Āśrāvaṇā

126. The Āśrāvaṇā should be [performed] with twice repeated Karaṇas[125] of the Vistāra[126] Dhātu in [successive] sections (Kalās), and then with a gradual increment by two repeated Karaṇas.

127-128. It will consist of a pair of twenty-four syllables (varṇa) of which the first two, the eleventh, the fourteenth, the fifteenth and the twenty-fourth are heavy, and a [three-fold fifteen syllables of which] the first is light, the next seven including the eighth heavy the next six again light, the final [three] syllables being heavy.[127]

129-130. The Tāla in the Āśrāvanā will be as follows: three Śamyās, and a Tāla in the Uparipāṇī, two Śamyās and two Tālas and again a Śamyā and two Tālas, in the Samapāṇī, and suitable Uttara and Cañcatpuṭa [Tālas] of two Kalās.[128]

(Its example is corrupt and untranslatable)[129]

The Ārambha

131-132. The [constituting] syllables in the Ārambha are as follows: the first eight heavy, the next twelve and the final one light [in the first section], and the four heavy, eight light, one heavy, four light, four heavy [in the second section], eight light and the final (light) [will form the next section].[130]

333-134. It should be performed in three sections with the Karaṇas such as the Tāla the Ribhita[131] and the Hrāda[132] in which the Vistāra Dhātus[133] will preponderate, and in it an ascent will be followed by a descent[134]. And in it the Karaṇas will first be descending twice or thrice and then will be played in the reverse order, and then all these are to be repeated.[135]

135-136. Its first Tāla of three Kalās there will be a Śamyā of one Kalā, a Tāla of two Kalās, then a Śamyā of two Kalās a Tāla of two Kalās and a Sannipāta of two Kalās and a Ṣaṭpitāputraka and a Cañcatpuṭa of two Kalās.[136]

(Its example is corrupt and untranslatable)[137]

The Vaktrapāṇi

137. The music of the Vaktrapāṇi will include the Karaṇas of the Ābiddha[138] [Dhātu] and it has two members Ekaka of Vṛtt (= pravṛtta)[139] and it is to have in its music half the member of the Vyañjana[140] Dhātus.

138-139. [The syllabic scheme of] the Vaktrapāṇi will be as follows: five heavy, six light, four times heavy, two heavy one light, four heavy, four light, three heavy, eight light and one heavy.[141]

140. The scheme of the Śamyā and the Tāla used in the Madraka song of two Kalās, will be used in the Vaktrapāṇi, but at the Mukha (beginning) it will consist of eight Kalās.[142]

141-142. The Tāla in the Mukha and Pratimukha of the Vaktrapāṇi will be as follows: a Śamyā, a Tāla, a Tāla, a Śamyā, and a Tāla, a Śamyā, a Tāla and a Sannipāta and four Pañcapāṇīs.[143]

(Its example is corrupt and untranslatable)[144]

The Saṃghoṭanā

143. The music of the Saṃghoṭanā will be by means of three Karaṇas of the Vistāra[145] [Dhātu] class and it will observe the Citra[146] and the Vṛtta[147] Styles of Procedure, and the three [such Karaṇas] will be repeated and will [gradually] rise.

144-145.[148] The syllables (lit. sequence of heavy and light syllables) of the theme of the Saṃghoṭanā will be as follows: two heavy, eight light, two heavy, one light, one heavy, one light, four light, eight light and heavy in the end.

146. In the Saṃghoṭanā, the Vīṇā taken with the two hands by its beam (daṇḍa), should be played with the fingers of the right hand and the two thumbs.

147.[149] The Saṃghoṭanā is so called because of the playing together (saṃghoṭana) of the Consonant and the Dissonant notes together with the remaining Assonant ones. Its Tāla, as in the Śīrṣaka will consist of the Pañcapāṇis.

(Its example is corrupt and untranslatable)[150]

148-149. [The syllabic scheme of] the Parighaṭṭanā, is as follows: eight heavy, twenty-four light[151], one heavy, sixteen light and two heavy.

150. Its music should consist of many Karaṇas of the Vyañjana [Dhātu] and should be performed with Upavahana (=Upohana) by clever hands.

151. Its Tāla will be Saṃparkeṣṭākaḥ [as it will stand] combined with the Karaṇa of the Dhātu (i.e. Vyañjana) due to the syllabic scheme [of the Parighaṭṭanā][152].

The Mārgāsārita

151-152. The syllabic scheme of the Mārgāsārita in its Vastu will be as follows: four heavy, eight light, eight heavy, eight light and the final heavy.

153. The instrumental music in the Mārgāsārita will consist of Karaṇas of the Vistāra and Ābiddha Dhātus, and it will observe all Tālas agreeing with its syllabic scheme.

(The example is corrupt and untranslatable)

154. Or it may be: four heavy, eight light, three heavy, three light, and heavy in the end. (The example is corrupt).

The Līlākṛta

155. The expert producer, as an occasion will arise, should perform the Līlākṛta as well as Abhisṛta and Parisṛta according to the rules of the short Āsārita, and it should observe Tālas sweet to hear.

The Āsāritas may be long (jyeṣṭha), medium (madhya) and short (kaniṣṭha). They in [relation to] their Tāla and measurement, will be explained in due order in the rules on Tālas.[153]

156. These are to be known about notes arising form the body of the Vīṇā. I shall next explain the characteristics of the hollow musical instruments (sūṣirātodya).

Here ends the Chapter XXIX of Bharata’s Nāṭyaśāstra, which treats of the Rules of the Stringed Musical Instruments.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

The notes marked-out for amplification are the Aṃśa notes of the Jātis (See 15 below). In the present case, Madhyama only is the Aṃśa note of the Ṣaḍjodīcyavatī (°cyavā), and while both Madhyama and Pañcama are such notes to the Ṣaḍjamadhyā. See XXVIII, 84, 91.

[2]:

As songs included in the performance of a play, were to serve its principal purpose which was the evocation of Sentiments, the author discusses here how Jātis can be applied for this purpose. The seven notes which have already been assigned to different Sentiments (XIX. 31-40), played an important part in this connexion. All these ultimately led to the formation of the Rāgas of the later Indian Music, in which the particular melody-types were meant not only to create a Sentiment appropriate to a situation in a play, but also to act on the hearers’ emotion in such a way that they might experience in imagination the particular situations described in isolated songs as well.

[3]:

Ṣaḍja and Ṛṣabha are respectively included into the Graha notes of the Ṣaḍjī and Ārṣabhī Jātis. See XXVIII. 88, 89, 92.

[4]:

Niṣāda and Gāndhāra are respectively included into the Aṃśa notes of the Naiṣādī and the Ṣaḍjakaiśikī Jātis. See XXVIII. 83-84.

[5]:

Dhaivata is included into the Aṃśa notes of the Dhaivati Jāti. See XXVIII. 81.

[6]:

As Gāndhāra and Niṣāda are not Aṃśa notes in the Dhaivatī, it is not clear how this Jāti can be applied in the Pathetic Sentiment. Cf. XIX. 38-40.

[7]:

Ga and ni are included into the Aṃśa notes of both the Gāndhāri and Raktagāndhārī Jātis. See XXVIII. 89-90.

[8]:

Ma and pa are included into the Aṃśa notes of the Madhyama Pañcamī, Gāndharapancamī and Madhyamodīcyavā Jāti. See XXVIII. 80.

[9]:

See below note 1 on 17-18.

[10]:

See below note 1 on 23-28.

[11]:

The Varṇa means the production of notes in a particular way i.e., in a particular order, pitch or with a particular grouping. SR. defines the term as “gānakriyocyate varṇaḥ”; (1. 6. 1.)

In explaining this Sbh. says

“svarāṇāṃ vakṣyamāṇaprakāreṇa gānakriyā gānakaraṇam uccāraṇamiti yāvat | sāvarṇaśabdenocyate”.

But he also adds the view of Mataṅga as follows:

“yatra tāne mañcaranti svarā antānta (ānyonya?)”

The Varṇas are used to make up the Alaṃkāras (see below 23ff.) It is probably this term which we meet with in Kālidāsa (“hasavadiyā vam?pari??ṃ karedi”, Śak. V).

[12]:

See below note I on 23-28.

[13]:

See below note 1 on 18-19.

[14]:

See below note 2 on 18-19.

[15]:

See below note 3 on 18-19.

[16]:

See below note 4 on 18-19.

[17]:

Example: sa ri ga ma pa dha ni.

[18]:

Ex: ni dha pa ma ri sa.

[19]:

Ex: sa sa sa sa or ma ma ma etc.

[20]:

Ex: sa ri ga ga ri sa, ri ga ma ma ga ri etc.

[21]:

Varṇas embellishing the notes of a song seems to enhance its power of evoking Sentiments.

[22]:

The Alaṃkāra known in later writing also as Varṇālaṃkāra, Svarālaṃkāra or Mūrchanālaṃkāra, was evidently means to embellish songs. It seems that without these proper Alaṃkāras a song remained merely a chant, and authorities differ very much among themselves about the number and definitions of the different Alaṃkāras. See below notes on 43ff: also GS. pp. 124ff.

[23]:

Written in NS. as two words (Nivṛttaḥ Pravṛttaḥ), but this is probably an error. Cf. SR (1.6. 47) where we have Saṃnivṛtta-pravṛttaḥ.

[24]:

Written in some versions of NŚ. as Vidhūta also.

[25]:

See Bd. (126-126) SR. has under this head two different names with different definitions.

[26]:

SR. (I. 6. 5-6) has Krama in its place.

[27]:

SR. (loc. lit.) has Prastāra in its place.

[28]:

See Bd. (128-129) omits Nivṛttapravṛtta, Recita, Kampita and Sama; this seems to be due to the loss of a hemistich in the text. SR. (I. 6. 26-29) has twenty-five names under this head, and they have been differently defined.

[29]:

See Bd. (130-131). Though some names are in a corrupt form, this text seems to follow NŚ. SR. (I. 6. 14-15) gives thirteen names and the common names have different definitions.

[30]:

See Bd. (132). SR (I. 6. 26) has the same names here as under the previous head (ārohi-varṇa), but with a direction that the notes are to be produced in these in descending order (avaroha-krama).

[31]:

This relates to the seven very old types of songs such as, Madraka, Oveṇaka, Aparāntaka, Prakarī, Ullopyaka, Rovindaka and Uttara (NŚ. XXXI. 220-221; SR. V. 58). Some authorities add seven more names (SR. V. 59.)

[32]:

It appears from this that the Dhruvās were a kind of chant, an early form of songs.

[33]:

This again shows that the Dhruvās were a kind of chant. For according to this passage, the Varṇas (i.e. the Varṇālaṃkāras) made the words (pada) of the song obscure by softening them.

[34]:

See Bd. (133-135) seems to be corrupt and it omits some names from the list. SR. has nothing analogous.

[35]:

The monotonic Varṇas are in general use, while the rest are to be used only to give special character to a song.

[36]:

These characteristics as defined in later works such as SR. (I. 6. 9ff.) vary from that given in NŚ.

[37]:

The definitions of the Alaṃkāras are not always very clear. But with the help of Bd. which in many matters seems to be in general agreement with NŚ., they may be rightly interpreted. It is a pity that the former work has not been properly edited.

See D. 100-101; Bd. pp. 35, 47. Besides in these places, Bd. quotes verbatim though in a corrupt form, the definitions of Alaṃkāras in 140-169 (pp. 44-47). These have been referred to in the foot-notes to the translation whenever necessary.

[38]:

1 See D. 101; Bd. ibid.

[39]:

See D. 101; Bd. ibid.

[40]:

See D. 101; Bd. ibid.

[41]:

See D. 106; Bd. pp. 36, 47.

[42]:

See D. 102-103; Bd. ibid.

[43]:

See D. 103; Bd. ibid.

[44]:

See Bd. ibid.

[45]:

Bd. ibid.

[46]:

See D. 107; Bd. ibid.

[47]:

See D. 107; Bd. ibid.

[48]:

See D. 104; Bd. pp. 37, 47.

[49]:

The NS. has the name of pitches as mandra (low), madhya (medium) and tāra (high, lit. loud). But in the passage in hand it has mandra (low), tāra (medium, lit. loud), tāratara (high, lit. extra-loud) in their places; cf. D. 8. It is not apparent why the term madhya (medium) has been given up here. See XIX. 45ff; 58-59 ff.

[50]:

See note 2 above.

[51]:

See note 2 or 49-50 above.

[52]:

See D. 104-105; Bd. pp. 37, 47.

[53]:

See D. 105-106: Bd. ibid.

[54]:

Bd. (p. 37, 48) has Prastāra (perhaps wrongly) for Prasvāra

[55]:

See Bd. pp. 38, 48.

[56]:

Bd. ibid. om. Apāṅgika.

[57]:

See Bd. pp. 38, 48.

[58]:

Bd. (pp. 39, 48) has Upalolaka for Avaloka.

[59]:

See Bd. ibid.

[60]:

See Bd. ibid.

[61]:

NS. puts this after 69, though serially it comes after 56. See Bd. 164 and also pp. 42, Bd. has the name as Udgīti.

[62]:

See Bd. pp. 39, 48.

[63]:

See Bd. pp. 40, 48.

[64]:

See Bd. ibid.

[65]:

See Bd. ibid.

[66]:

See Bd. ibid. In p. 48. Bd. writes Udvāhita (perhaps wrongly) for Udghaṭṭita.

[67]:

See Bd. pp. 40, 49.

[68]:

See Bd. ibid.

[69]:

See Bd. p. 41.

[70]:

See Bd. p. 41.

[71]:

See Bd. p. 42.

[72]:

See Bd. (p. 42) which writes the name as Vidhūta.

[73]:

See Bd. pp. 42-43.

[74]:

The other long vowels are probably ā, ī and ū.

[75]:

Compare the Karaṇas of dance mentioned in IV. 29ff.

[76]:

Bd. (167) reads the second half of this passages as “ebhiralaṃkartavyā gītirṇāmāvirodhena”, songs should be decorated with these Alaṃkāras without [coming into] conflict [with their spirit].

[77]:

See XXIII. 31-32.

[78]:

See above note 1 on XXVIIL 8.

[79]:

See Bd. 171 ff.; SR. I. 8. 14ff. On the Gīti depended an ancient system of classification of rhythms. The Gīti also included special formations of syllable and variation in speed. See Banerji, GS. II. pp. 72-73.

[80]:

See note 1 on 76 above.

[81]:

Also mentioned as gati-vṛtti in XXIX. 102ff. Śārṅgadeva uses the term mārga to indicate vṛtti or gati-vṛtti. See SR. V. II. On Mārga or Vṛtti too was based an ancient system of classifying of rhythms, including that of Tāla. See GS. II. p. 72.

[82]:

See XXXII. below. From this passage too it appears that the Dhruvās were a kind of chant.

[83]:

See before the note 1 on XXVIII. 8.

[84]:

This is evidently a grammatical metaphor. The Dhātus (roots) relate to different aspects of strokes in playing stringed instruments. Śārṅgadeva (V. 122). says: “ye prahāraviśevītyāḥ kharāste dhātavo matāḥ”

[85]:

See SR. V. 123-127.

[86]:

As Dhātus relate to the tata or stringed instruments, we shall translate vāditra as ‘stringed instruments.’ See below 91 (vīṇā-vādye karaṇadhātuḥ) and 101 (viṇāyāṃ vyañjaṇo dhātuḥ).

[87]:

“ekaprahārabhavo vistārajaḥ” (Kn. on SR. VI. 183).

[88]:

See above note 2 on 82.

[89]:

Anubandha here means ‘mixture’ or ‘combination.’ See Kn. on SR. VI. 147. It may be that in the Anubandha variety of the Karaṇa Dhātu, the strokes are 3 + 5, 3 + 9, or 5 + 7, 5 + 9 etc.

[90]:

See above note 1 to 92. In the Anubandha of the Ābiddha Dhātu too, the number of strokes are to be increased by adding together the numbers available in other Dhātus.

[91]:

Savya means ‘right’ as well. See Apte sub voce, But here it is to be taken in its generally accepted sense.

[92]:

Ibid.

[93]:

See above note 1 of 92.

[94]:

See above note 1 on 78.

[95]:

See XXXI.

[96]:

The word laya signifies the speed at which a piece of music is performed. There are three primary degrees of speed i.e. rate of movement, in the Indian music: slow (vilambita), medium (madhya) and quick (druta). As in the European music, there is no fixed absolute measure of time for different degrees of speed mentioned here. See GS. II. p. 33. Śārṅgadeva (V. 48). defines laya as “kriyāmantaraviśrāntiḥ”

[97]:

See above note 1 on 76.

[98]:

The Yati means ‘succession of different kinds of speed’ in the whole song, e.g. a song may be sung at a slow speed in the beginning, at a medium speed next and at a quick speed in the end, or these speeds at the singer’s discretion may be taken up in a different order, See SR. V, 50ff. and Kn. theron.

[99]:

Mārga in the text, should be taken here as graha-mārga, which has been twice used later in this passage. Graha-mārga means the manner of following a song or a piece of music by an instrument of Tāla. See GS. I. pp. 197ff, 469. SR. V. 54-56, 58 and VI. 186-187.

See SR. V. 51.

See SR. V. 51-52.

See SR. V. 52-53.

See below 105.

This term has been used also in relation to songs. See XXVIII, 38ff. and XXIX. Iff.

See below 120 for the definition of a Vipañcī.

Cf. SR. VI. 112.

Cf. SR. VI. 113-114.

Cf. SR. VI. 115.

Cf. SR. VI. 115-116.

Cf. SR. VI. 117.

Cf. SR. VI. 118.

See cf. SR. VI. 119-120.

This Citrā (vīṇā) probably developed later into Persian sitār. It may be that the Greek kithara with seven strings is also connected with it. The seven strings in the Citrā, were probably meant for producing seven notes of the octave.

The nine strings of the Vipañcī were probably for producing seven notes together with two Kākalī notes (svara-sādhāraṇa, XXVIII. 36).

See V. 8-11, 18-21.

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.

It seems that this item was not originally included in the Bahir-gītas (See V. 8-11).

Short, medium and long.

These are called Bahir-gītas because they were outside (bahis) the performance of the play and were included in its Preliminaries. See V.

See V. 8-11, 18-21.

See XXIX 82.

ibid. also SR. VI. 134-144.

Cf. SR. VI. 182-184.

Cf. SR. VI. 186ff.

It seems that these passages evidently corrupt, included magical formulas (mantra) for warding off evils. See V. 45-55, 176.

The text the of the passage, is probably still more corrupt. Cf. SR. VI. 200ff.

See XXIX. 91-92., SR. VI. 145-146.

ibid.

See XXIX. 83-90., cf. SR VI. 134ff.

cf. SR. VI. 197.

The translation is tentative. Cf. SR. VI. 198-199.

Cf. SR. VI. 204 ff.

See note 2 of 129-30 above.

See XXIX. 82, 93-94; cf. SR. VI. 148-150.

XXXI. 201. ff.

See XXIX. 95-101. cf. SR. VI. 151-160.

Cf. SR. VI. 209-210.

Cf. SR. VI. 211.

Cf. SR. VI. 212.

See note 2 of 129-130 above.

See XXIX 83-90; cf. SR. VI. 134ff.

See XXIX 83-90; cf. SR. VI. 134ff. See XXIX. 103; cf. SR. V. 11.

ibid.

Cf. SR. VI. 213.

The translation is tentative

See note 2 of 129-130.

lit. twice 8 light, twice 4 light.

Cf. SR. VI. 211ff. (155)

See XXXI.