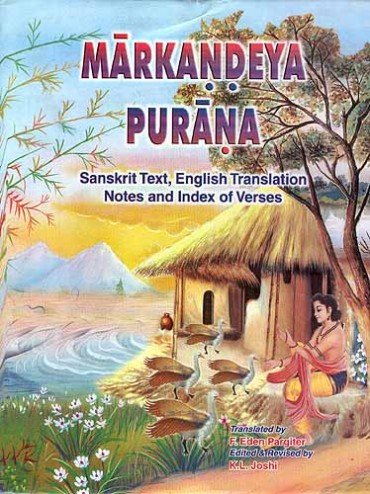

The Markandeya Purana

by Frederick Eden Pargiter | 1904 | 247,181 words | ISBN-10: 8171102237

This page relates “marutta’s exploits” which forms the 128th chapter of the English translation of the Markandeya-purana: an ancient Sanskrit text dealing with Indian history, philosophy and traditions. It consists of 137 parts narrated by sage (rishi) Markandeya: a well-known character in the ancient Puranas. Chapter 128 is included the section known as “conversation between Markandeya and Kraustuki”.

Canto CXXVIII - Marutta’s exploits

Avīkṣit returned and presented his son to his father Karandhama, and there was great rejoicing—The boy grew up, learned in sacred lore and skilful with all weapons—Karandhama resigned the kingdom, but Avīkṣit refused it because of the shame of his former captivity—Marutta was made king, and Karandhama retired to the forest.

Mārkaṇḍeya spoke:

Then the prince, taking that beloved son and followed by his wife[2] and the brāhmans and Gandharvas, went to his city. Reaching his father’s palace he extolled his father’s feet with respect; and so did his slender-limbed wife, the bashful princess. And the prince holding his infant son addressed king Karandhama, who was seated on the throne of justice in the midst of kings,—“Behold this face of thy grandson who rests in my lap, as I promised formerly to thee for my mother’s sake at the ‘What-want-ye?’ vow.” So saying he laid that son then on his father’s lap, and related to him everything as it had occurred. The king embracing his grandson, while his eyes were beclouded with teats of joy, felicitated himself again and again in saying “Fortunate am I!” Then he duly paid honour to the assembled Gandharvas with the arghya offering and other presents,[3] forgetting other needs by reason of his joy.[4]

In the city then there was great rejoicing in the houses of the citizens, who exclaimed — “A son has been horn to our master!” O great muni. In that glad and opulent city sportive courtesans of the prettjest forms danced an exquisite dance to the accompaniment of songs and musical instruments. And the king with glad mind bestowed on the chief brāhmans both gems and riches, cattle, clothing and ornaments.

The boy grew thenceforward, as the moon ivaxes in its bright fortnight. He was the source of pleasure to his parents, and the desire of the people. He acquired the Vedas first from the religious teachers, O muni, then skill in all kinds of weapons, then complete knowledge of archery. When he had completed his efforts in the use of the sword and how, he next overcame toil like a hero in learning the use of other weapons also. Then he obtained weapons from Bhārgava,[5] descendant of Bhṛgu,—bowing modestly and intent oū pleasing his guru, O brāhman. Accomplished in the use of weapons, skilled in the Veda, thoroughly master of the knowledge of archery, deeply versed in all sciences—none such had there been before him.

Viśāla also, on hearing all this story of his daughter and of the ability of his daughter’s son, rejoiced exceedingly in mind.

Now the king Earandhama had attained his wishes, in that he had seen his son’s son and had offered many sacrifices, and had bestowed gifts on those who asked. He had performed all ceremonies; he was united with his fellow-kings[6]; having safeguarded the earth righteously, he had conquered his enemies; he was endowed with strength and intelligence. Being desirous of departing to the forest he addressed his son Avīkṣit— “My son, I am old, I am going to the forest, take over the kingdom from me. I have done what ought to be done; nothing remains but to anoint thee. Do thou who art highly accomplished in thy opinions take the kingdom which I have transfered to thee.” Being addressed thus, Avīkṣit the prince, respectfully bowing down, said to his father who was desirous of going[7] to the forest to perform austerities,—

“I will not, dear father, do the safeguarding of the earth; shame departs not from my mind; do thou appoint some one else to the kingdom. Since I when captured was delivered by my dear father and not by my own valour, how much manliness then have I? The earth is protected by real men. I who was not sufficient to protect even myself, how shall I, being such, protect the earth? Cast the kingdom on some one else. On the same level as a woma[8] is the man who is downright injured[9] by another. And my soul has been delivered from delusion by thee, sir,[10] who hast delivered me from bondage. How shall I, being such, who am on the same level as a woman, become king?”

The father spoke:

Not distinct[11] in sooth is the father from the son, nor the son from the father. Not delivered by any one else then wast thou, who wast delivered by thy father.

The son spoke:

I cannot direct my heart in any other wise, O king. There is exceeding shame in my heart—I, who was delivered by thee. He who has been rescued by his father consumes the glory acquired by his father; and let not the man, who is known by reason of his father, exist in the family. Let mine be that course, which is the course of those who have themselves amassed riches, who have themselves attained to fame, who have themselves come forth safe out of difficulties!

Mārkaṇḍeya spoke:

When he, although exhorted[12] often by his father, spoke thus, O muni, the king then appointed his[13] son Marutta to the kingdom. Receiving from his grandfather the sovereignty as authorized by his father, he ruled well, inspiring gladness among his friends.

And king Karandhama, taking Vīrā also, departed to the forest to practise austerities with voice, body and mind restrained. After practising very arduous austerities there a thousand years, the king quitted his body and gained the world[14] of Indra. His wife Vīrā then practised austerities a hundred years longer, with her hair matted and her body covered with dirt and mud, desirous of gaining the same world as her high-souled lord who had reached Svarga, making fruits and roots her food, dwelling in Bhārgava’s hermitage, encircled by wives of twice-born men, and sustained by the devoted attendance of the twice-born.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Canto cxxix in the Calcutta edition.

[2]:

For padbhyāṃ read patnyā, as in the Poona edition.

[3]:

For ’rdhyādinā read’ rghyādinā, as in the Poona edition.

[4]:

The Poona edition amplifies this and, instead of the second line as in the Calcutta edition, reads—

“Then he duly paid honour to the assembled Gandharvas with the arghya offering and other presents joyfully, and dismissed them with propriety. He continues playing with his grandson, forgetful of other needs.”

[5]:

That is Śukra Ācārya (comment.). He was the preceptor of the Asuras.

[6]:

Sa-varṇair, = māṇḍalika-nṛpaiḥ (comment.), “with hia provincial kings,” “with his vassal kings.”

[7]:

For yiyāsus read yiyāsuṃ, as in the Poona edition.

[8]:

For mantrī sadharmaḥ, read sa strī-sadharmaḥ, as in the Poona edition.

[9]:

Ava-druhyate; the verb ava-druh is not in the dictionary.

[10]:

For ātmā’mohāya bhavato the Poona edition reads ātmā’mohāc ca bhavatā; and the comment, says amohāt = snehāt (which seems strange). The meaning then would be, “Since I myself have been delivered from bondage by thee, sir, out of affection, how shall I &o.” But I have ventured to read ātmā mohāccabhavatā.

[11]:

Na bhinna; according to the comment, this means putra-nirūpita-bheda-viśiṣto na.

[12]:

For yadāpy ukto read yadāprokto, as in the Poona edition. Avīkṣit is mentioned in the MahāBhārata, Āśvam.-p. iv. 80-85, but rarely elsewhere. His name chiefly occurs in the patronymic form Āvīkṣita applied to Marutta. There was another Avīkṣit, a son of Kuru, Ādi-p. xciv. 3740.

[13]:

Tasya, i.e., Avīkṣit’s.

[14]:

For salokatām read sa-lokatām.