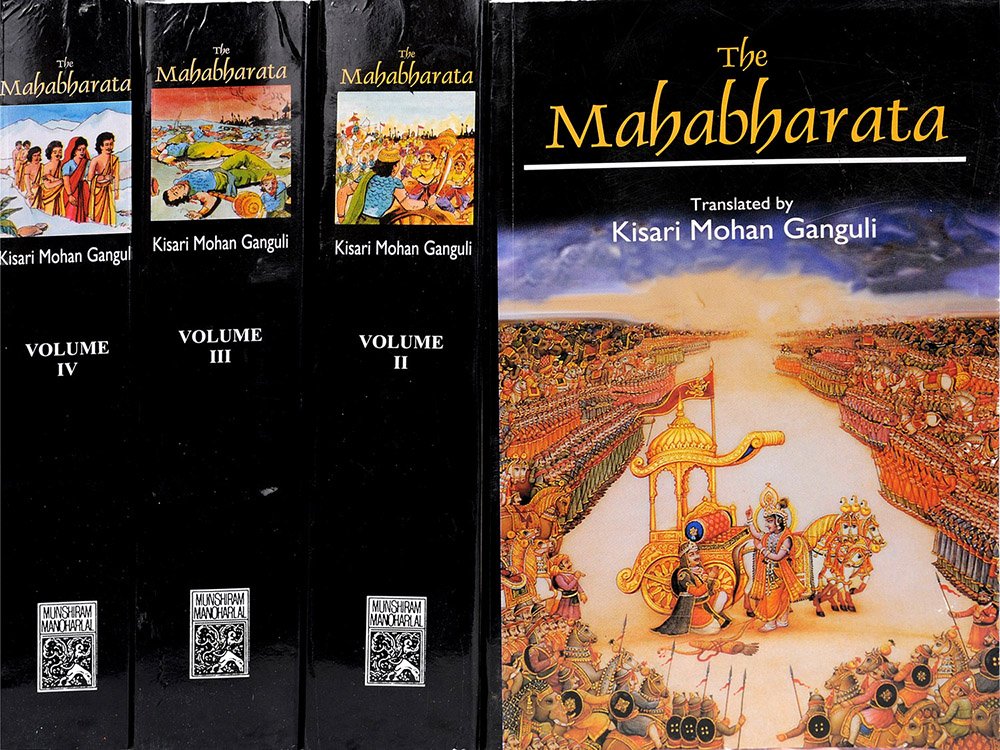

Mahabharata (English)

by Kisari Mohan Ganguli | 2,566,952 words | ISBN-10: 8121505933

The English translation of the Mahabharata is a large text describing ancient India. It is authored by Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa and contains the records of ancient humans. Also, it documents the fate of the Kauravas and the Pandavas family. Another part of the large contents, deal with many philosophical dialogues such as the goals of life. Book...

Section CCXXIII

"Yudhishthira said, 'Tell me, O grandsire, by adopting what sort of intelligence may a monarch, who has been divested of prosperity and crushed by Time’s heavy bludgeon, still live on this earth.'

"Bhishma said, 'In this connection is cited the old narrative of the discourse between Vasava and Virocana’s son, Vali. One day Vasava, after having subjugated all the Asuras, repaired to the Grandsire and joining his hands bowed to him and enquired after the whereabouts of Vali. Tell me, O Brahman, where I may now find that Vali whose wealth continued undiminished even though he used to give it away as lavishly as he wished. He was the god of wind. He was Varuna. He was Surya. He was Soma. He was Agni that used to warm all creatures. He became water (for the use of all). I do not find where he now is. Indeed, O Brahman, tell me where I may find Vali now. Formerly, it was he who used to illumine all the points of the compass (as Surya) and to set (when evening came). Casting off idleness, it was he who used to pour rain upon all creatures at the proper season. I do not now see that Vali. Indeed, tell me, O Brahmana, where I may find that chief of the Asuras now.'

"Brahman said, 'It is not becoming in you, O Maghavat, to thus enquire after Vali now. One should not, however, speak an untruth when one is questioned by another. For this reason, I shall tell you the whereabouts of Vali. O lord of Saci, Vali may now have taken his birth among camels or bulls or asses or horses, and having become the foremost of his species may now be staying in an empty apartment.'

"Sakra said, 'If, O Brahman, I happen to meet with Vali in an empty apartment, shall I slay him or spare him? Tell me how I shall act.'

"Brahman said, 'Do not, O Sakra, injure Vali, Vali does not deserve death. You should, on the other hand, O Vasava, solicit instruction from him about morality, O Sakra, as you pleasest.'

"Bhishma continued, 'Thus addressed by the divine Creator, Indra roamed over the earth, seated on the back of Airavata and attended by circumstances of great splendour. He succeeded in meeting with Vali, who, as the Creator had said, was living in an empty apartment clothed in the form of an ass.'

"Sakra said, 'You are now, O Danava, born as an ass subsisting on chaff as your food. This your order of birth is certainly a low one. Dost you or dost you not grieve for it? I see what I had never seen before, viz., thyself brought under the sway of your enemies, divested of prosperity and friends, and shorn of energy and prowess. Formerly, you used to make progress through the worlds with your train consisting of thousands of vehicles and thousands of kinsmen, and to move along, scorching everybody with your splendour and counting us as nought. The Daityas, looking up to you as their protector, lived under your sway. Through your power, the earth used to yield crops without waiting for tillage. Today, however, I behold you overtaken by this dire calamity. Dost you or dost you not indulge in grief for this? When formerly you usedst, with pride reflected in your face, to divide on the eastern shores of the ocean your vast wealth among your kinsmen, what was the state of your mind then? Formerly, for many years, when blazing with splendour, you usedst to sport, thousands of celestial damsels used to dance before you. All of them were adorned with garlands of lotuses and all had companions bright as gold. What, O lord of Danavas, was the state of your mind then and what is it now? You had a very large umbrella made of gold and adorned with jewels and gems. Full two and forty thousand Gandharvas used in those days to dance before you.[1] In your sacrifices you had a stake that was very large and made entirely of gold. On such occasions you were to give away millions upon millions of kine. What, O Daitya, was the state of your mind then? Formerly, engaged in sacrifice, you had gone round the whole earth, following the rule of the hurling of the Samya: What was the state of your mind then?[2] I do not now behold that golden jar of thine, nor that umbrella of thine, nor those fans. I behold not also, O king of the Asuras, that garland of thine which was given to you by the Grandsire.'

"Vali said, 'You seest not now, O Vasava, my jar and umbrella and fans. You seest not also my garland, that gift of the Grandsire. Those precious possessions of mine about which you askest are now buried in the darkness of a cave. When my time comes again, you will surely behold them again. This conduct of thine, however, does not become your fame or birth. Thyself in prosperity, you desirest to mock me that am sunk in adversity. They that have acquired wisdom, and have won contentment therefrom, they that are of tranquil souls, that are virtuous and good among creatures, never grieve in misery nor rejoice in happiness. Led, however, by a vulgar intelligence, you indulgest in brag, O Purandara! When you shalt become like me you shalt not then indulge in speeches like these.'"

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

The Burdwan translator renders the second line as "six thousand Gandharvas used to dance before you seven kinds of dance."

[2]:

Both the vernacular translators have misunderstood this verse. A samya is explained as a little wooden cane measuring about six and thirty fingers breadth in altitude. What Vali did was to go round the Earth (anuparyagah, i.e., parihrityagatavan) throwing or hurling a samya. When thrown from a particular point by a strong man, the samya clears a certain distance. This space is called a Devayajana. Vali went round the globe, performing sacrifices upon each such Devayajana.

Conclusion:

This concludes Section CCXXIII of Book 12 (Shanti Parva) of the Mahabharata, of which an English translation is presented on this page. This book is famous as one of the Itihasa, similair in content to the eighteen Puranas. Book 12 is one of the eighteen books comprising roughly 100,000 Sanskrit metrical verses.