Mahabharata (English)

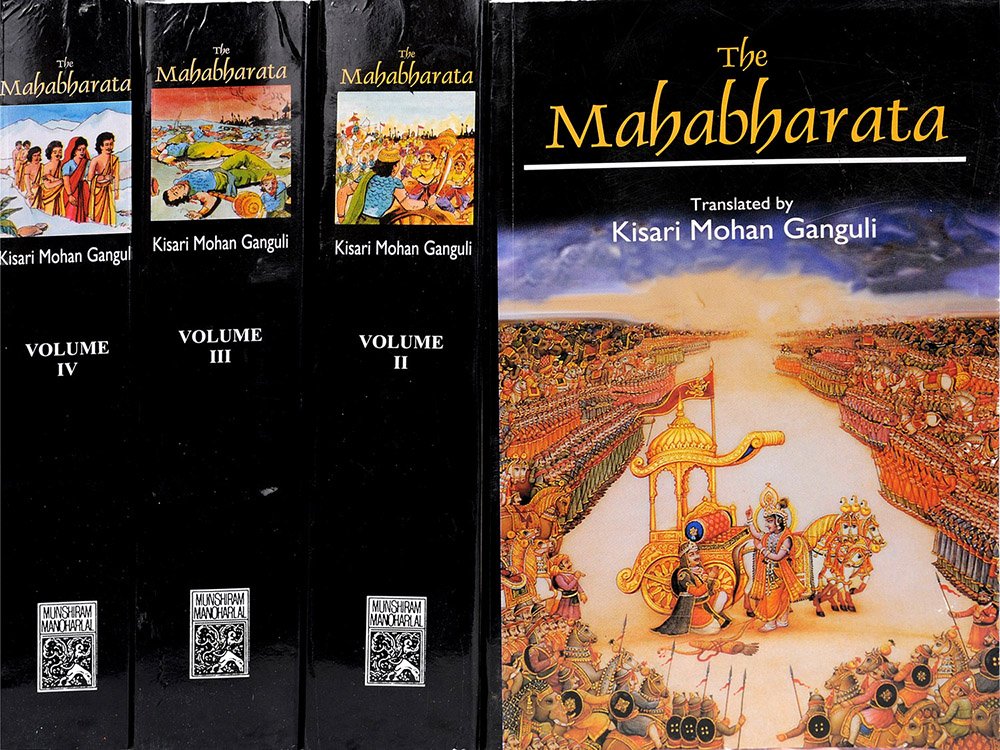

by Kisari Mohan Ganguli | 2,566,952 words | ISBN-10: 8121505933

The English translation of the Mahabharata is a large text describing ancient India. It is authored by Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa and contains the records of ancient humans. Also, it documents the fate of the Kauravas and the Pandavas family. Another part of the large contents, deal with many philosophical dialogues such as the goals of life. Book...

Section CLX

"Vaisampayana said, "On hearing these words of the Brahmana, his wife said,

'You should not, O Brahmana, grieve like an ordinary man. Nor is this the time for mourning. You have learning; you knowest that all men are sure to die; none should grieve for that which is inevitable. Wife, son, and daughter, all these are sought for one’s own self.

As you are possessed of a good understanding, kill you your sorrows. I will myself go there. This indeed, is the highest and the eternal duty of a woman, viz., that by sacrificing her life she should seek the good of her husband. Such an act done by me will make you happy, and bring me fame in this world and eternal bliss hereafter.

This, indeed, is the highest virtue that I tell you, and you mayest, by this, acquire both virtue and happiness. The object for which one desires a wife has already been achieved by you through me.

I have borne you a daughter and a son and thus been freed from the debt I had owed you.

You are well able to support and cherish the children, but I however, can never support and cherish them like you.

You are my life, wealth, and lord; bereft of you, how shall these children of tender years—how also shall I myself, exist? Widowed and masterless, with two children depending on me, how shall I, without you, keep alive the pair, myself leading an honest life? If the daughter of thine is solicited (in marriage) by persons dishonourable and vain and unworthy of contracting an alliance with you, how shall I be able to protect the girl?

Indeed, as birds seek with avidity for meat that has been thrown away on the ground, so do men solicit a woman that has lost her husband.

O best of Brahmanas, solicited by wicked men, I may waver and may not be able to continue in the path that is desired by all honest men.

How shall I be able to place this sole daughter of your house—this innocent girl—in the way along which her ancestors have always walked? How shall I then be able to impart unto this child every desirable accomplishment to make him virtuous as thyself, in that season of want when I shall become masterless? Overpowering myself who shall be masterless, unworthy persons will demand (the hand of) this daughter of thine, like Sudras desiring to hear the Vedas.

And if I bestow not upon them this girl possessing your blood and qualities, they may even take her away by force, like crows carrying away the sacrificial butter.

And beholding your son become so unlike to you, and your daughter placed under the control of some unworthy persons, I shall be despised in the world by even persons that are dishonourable, and I will certainly die.

These children also, bereft of me and you, their father, will, I doubt not, perish like fish when the water dries up. There is no doubt that bereft of you the three will perish: therefore it behoves you to sacrifice me.

O Brahmana, persons conversant with morals have said that for women that have borne children, to predecease their lords is an act of the highest merit. Ready am I to abandon this son and this daughter, these my relations, and life itself, for you.

For a woman to be ever employed in doing agreeable offices to her lord is a higher duty than sacrifices, asceticism, vows, and charities of every description. The act, therefore, which I intend to perform is consonant with the highest virtue and is for your good and that of your race.

The wise have declared that children and relatives and wife and all things held dear are cherished for the purpose of liberating one’s self from danger and distress. One must guard one’s wealth for freeing one’s self from danger, and it is by his wealth that he should cherish and protect his wife. But he must protect his own self both by (means of) his wife and his wealth.

The learned have enunciated the truth that one’s wife, son, wealth, and house, are acquired with the intention of providing against accidents, foreseen or unforeseen. The wise have also said that all one’s relations weighed against one’s own self would not be equal unto one’s self.

Therefore, revered sir, protect your own self by abandoning me.

O, give me leave to sacrifice myself, and cherish you my children. Those that are conversant with the morals have, in their treatises, said, that women should never be slaughtered and that Rakshasas are not ignorant of the rules of morality.

Therefore, while it is certain that the Rakshasa will kill a man, it is doubtful whether he will kill a woman. It behoves you, therefore, being conversant with the rules of morality, to place me before the Rakshasa.

I have enjoyed much happiness, have obtained much that is agreeable to me, and have also acquired great religious merit. I have also obtained from you children that are so dear to me.

Therefore, it grieves not me to die. I have borne you children and have also grown old; I am ever desirous of doing good to you; remembering all these I have come to this resolution.

O revered sir, abandoning me you mayest obtain another wife. By her you mayest again acquire religious merit. There is no sin in this. For a man polygamy is an act of merit, but for a woman it is very sinful to betake herself to a second husband after the first.

Considering all this, and remembering too that sacrifice of your own self is censurable, O, liberate today without loss of time your own self, your race, and these your children (by abandoning me).'

"Vaisampayana continued, 'Thus addressed by her, O Bharata, the Brahmana embraced her, and they both began to weep in silence, afflicted with grief.'"

Conclusion:

This concludes Section CLX of Book 1 (Adi Parva) of the Mahabharata, of which an English translation is presented on this page. This book is famous as one of the Itihasa, similair in content to the eighteen Puranas. Book 1 is one of the eighteen books comprising roughly 100,000 Sanskrit metrical verses.

FAQ (frequently asked questions):

Which keywords occur in Section CLX of Book 1 of the Mahabharata?

The most relevant definitions are: Brahmana, Rakshasa, Vaisampayana, Brahmanas, Sudras, Vedas; since these occur the most in Book 1, Section CLX. There are a total of 8 unique keywords found in this section mentioned 15 times.

What is the name of the Parva containing Section CLX of Book 1?

Section CLX is part of the Vaka-vadha Parva which itself is a sub-section of Book 1 (Adi Parva). The Vaka-vadha Parva contains a total of 8 sections while Book 1 contains a total of 19 such Parvas.

Can I buy a print edition of Section CLX as contained in Book 1?

Yes! The print edition of the Mahabharata contains the English translation of Section CLX of Book 1 and can be bought on the main page. The author is Kisari Mohan Ganguli and the latest edition (including Section CLX) is from 2012.