Sahitya-kaumudi by Baladeva Vidyabhushana

by Gaurapada Dāsa | 2015 | 234,703 words

Baladeva Vidyabhusana’s Sahitya-kaumudi covers all aspects of poetical theory except the topic of dramaturgy. All the definitions of poetical concepts are taken from Mammata’s Kavya-prakasha, the most authoritative work on Sanskrit poetical rhetoric. Baladeva Vidyabhushana added the eleventh chapter, where he expounds additional ornaments from Visv...

Text 2.9

स चार्थः क इत्य् आह,

sa cārthaḥ ka ity āha,

What exactly is that meaning? In response he says:

saṅketitaś catur-bhedo jāty-ādir jātir eva vā ||2.8ab||

saṅketitaḥ—the assigned [meaning]; catur-bhedaḥ—has four kinds; jāty-ādiḥ—beginning from a category; jātiḥ—is a category; eva—only; vā—or else.

The assigned meaning has four varieties, beginning from jāti (category). Or else it is only the jāti.

jāti-guṇa-kriyā-saṃjñā-rūpaś catur-vidho’rthaḥ saṅketitaḥ. tatra jātir guṇaś ca siddha-rūpo vastu-dharmaḥ. padārtha-vyavahāra-yogyatā-nirvāhikā go-piṇḍādiṣu gotvādikā jātiḥ. viśeṣādhāna-hetur guṇaḥ. śuklādayo hi gavādīn sajātīyebhyo nīla-gavādibhyo vyāvartayanti. kriyā pūrvāparī-bhūtāvayavā pākādiḥ sādhya-rūpo vastu-dharmaḥ. saṃjñā tu ḍitthādi-dravyeṣu vaktrā yadṛcchayā sanniveśitaṃ ḍitthādi-śabda-svarūpam eva. eka-vyakti-vācakaḥ sety anye.

eṣv eva vyakty-upādhiṣu “gauḥ śuklaḥ pācako ḍitthaḥ” ity-ādeś catur-vidhasya śabdasya kramāt saṅketaḥ. na copādhiṣv artha-kriyā-kāritānupapattiḥ, tair vyakty-ākṣepāt. na caivaṃ vyaktiṣv eva saṅketo’stv iti vācyam, ānantya-vyabhicāra-doṣāpatteḥ. guṇādīnām apy eka-vyaktitvān na kiñcid anavadyam. teṣāṃ bhedāvabhāsas tv āśraya-bhedād eva na tu svataḥ, maṇi-darpaṇādibhedān mukha-bheda-vat.

athavā sarvatra jātir eva saṅketa-gocaraḥ. candra-candanaśaṅkhādiṣu “ayaṃ śuklo’yaṃ śuklaḥ” ity-ādi-pratīty-aviśeṣāc chuklatvādi. guḍa-taṇḍula-taila-pākādiṣu “ayaṃ pāko’yaṃ pākaḥ” iti pākatvam. bāla-vṛddha-śukādy-ukteṣu ḍitthādiṣu “ḍittho ’yam” iti ḍitthāditvam iti sarvatra tad-avagāhāt. catur-vidhānāṃ gavādi-śabdānāṃ jāty-ādi-catuṣkaṃ kramāt pravṛtti-nimittam, jātir eva vā sarveṣāṃ teṣām iti hy arthaḥ.

The assigned meaning, in the forms of jāti (category), guṇa (quality), kriyā (action; mode of being), or saṃjñā (name), has four varieties. Among them, jāti and guṇa are an entity’s attributes (vastu-dharma) which are established (siddha).[1]

Jāti, such as cowness in a cow, brings about the suitability of the usage of the meaning of the declined word. Guṇa is the cause of the attribution of a particularity. For instance, the white color distinguishes a cow from a dark cow of the same species (jāti). Kriyā is an entity’s attribute, such as cooking, that is in the process of being accomplished (sādhya): Its aspects are operations that are prior and subsequent. Saṃjñā, however, is simply the nature of a word such as Ḍittha (someone’s name) which is attributed to Ḍittha, and so on, by a speaker by that speaker’s will. Others say saṃjñā is a literally expressive word (vācaka) that denotes one individual (vyakti).[2]

There are four kinds of words, such as: a cow, white, cooking, and Ḍittha. The assignation of a word occurs only in reference to those ones sequentially (jāti, guṇa, kriyā, saṃjñā), which are the characteristics of a vyakti (an individual person, thing, or action). In those four characteristics, there is no inconclusive reasoning regarding the dealings involving things and actions, since they implicitly indicate the respective individuals (vyakti).[3] Nor can it be said that assignation takes place only in reference to individuals, because of the unwanted concomitant occurrence of the fault of discrepancy, since there is an infinity of individuals.[4]

Nothing is irreproachable, since even a quality (guṇa), and so on (kriyā, dravya), is only one: The appearance of the differences occurs only on account of the differences of the substratums; the difference is not inherent. It is like when one’s face looks different to oneself because of looking in different jewel-studded mirrors.[5]

Or else, in every instance only the jāti is the scope of assignation. For example: (1) Whiteness (not the particular shade of the white color), owing to a nonparticularity due to a perception like this in the moon, in sandalwood paste, in a conchshell, and the like: “This is white,” “This is white,” and so on, (2) The state of cooking, as regards cooking jaggery, cooking rice, cooking oil, and so on, owing to a nonparticularity due to this perception in every case: “This is cooking,” (3) The state of being Ḍittha, when a boy, an elder, and a parrot, and so on, say this about Ḍittha: “He is Ḍittha” because of an inclusion in that [state of being][6] every time.

The sense is simply this: Either these four: jāti, guṇa, kriyā, and saṃjñā, are the reason for the respective usage of the four kinds of words, such as: a cow, white, cooking, and Ḍittha, or else only the jāti relates to all of them.

Commentary:

Patañjali represents the first school of thought.[7] The Mīmāṃsakas say that only the jāti is referred to every time; Bhartṛhari agreed with the latter.[8] A sentence such as “This is the sky” uses Patañjali’s method because the sky, being unique, is not part of a category of skies.

The Mīmāṃsakas’ system is irreproachable because there is no discrepancy between such statements as “The sky is blue” and “The ocean is blue”. At first the category of blue is denoted. Afterward the particular kind of blue (the individual blue) is automatically understood.

Only an entity which belongs to a jāti can have a quality. But how can a statement such as “The moon is white” be justified, since the moon is a dravya, not a jāti? The answer is that a quality is attributed to the moon by thinking of the moon as a jāti. And that is done by considering that there is a multiplicity of moons insofar as there are unlimited universes.[9] Madhusūdana Sarasvatī writes: evam ākāśa-śabdo’pi tārkikāṇāṃ śabdāśrayatvādi-rūpaṃ yaṃ kañcid dharmaṃ puraskṛtya pravartate, sva-mate tu pṛthivyādi-vad ākāśa-vyaktīnāṃ janyānām anekatvād ākāśatvam api jātir eveti so’pi jāti-śabdaḥ, “Similarly, even the word ākāśa (ether) of the Logicians is used by their putting forth some particular attribute in the form of being the substratum of sound.[10] In our opinion, however, even the state of being ether is a jāti because, as in the case of earth and so on, the individual ethers that have been engendered [throughout millions of universes or else in the course of the series of creations and destructions of the world] are many, so even the state of being ākāśa is a word of a jāti.” (Gūḍhārtha-dīpikā 13.13). In like manner, a quality is attributed to any unique individual such as Ḍittha, for instance, by thinking of him as “the state of being Ḍittha,” which is a jāti (a category).

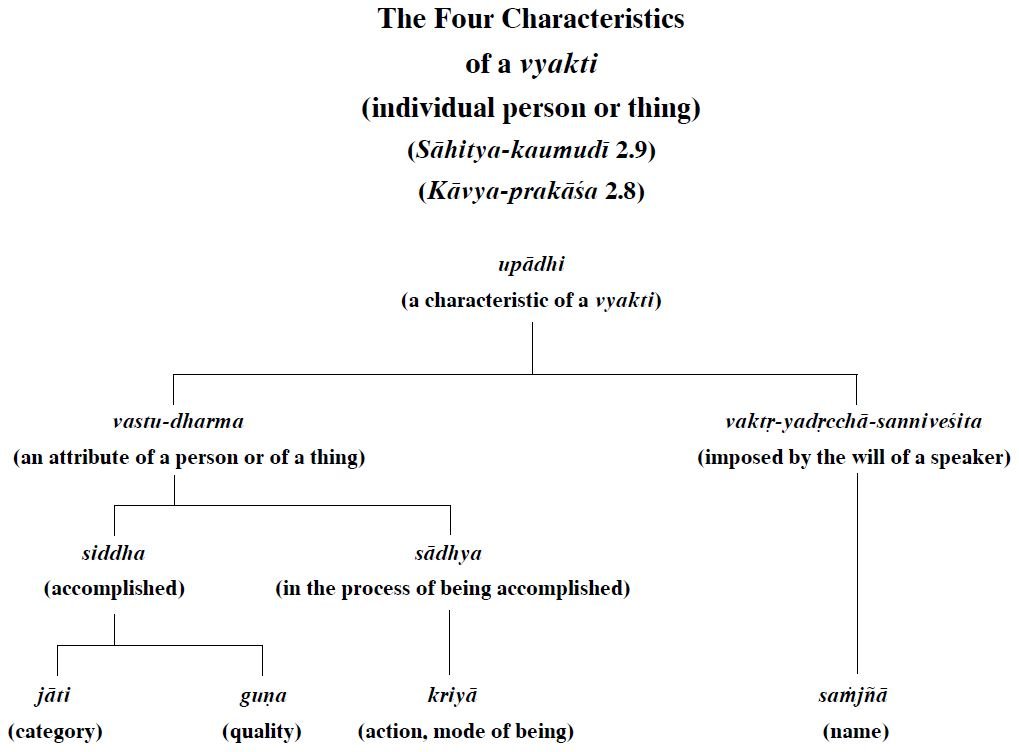

The Four Characteristics of a vyakti

(individual person or thing) (Sāhitya-kaumudī 2.9) (Kāvya-prakāśa 2.8)

upādhi—(a characteristic of a vyakti);

vastu-dharma—(an attribute of a person or of a thing);

vaktṛ-yadṛcchā-sanniveśita—(imposed by the will of a speaker);

siddha—(accomplished);

sādhya—(in the process of being accomplished);

jāti—(category);

guṇa—(quality);

kriyā—(action, mode of being);

saṃjñā—(name);

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

The term vastu-dharma (the attribute of an entity) means the same as dravya-dharma (Candrakalā-ṭīkā on Sāhitya-darpaṇa 2.4). The words dravya (unique entity)and saṃjñā (name)refer to the same concept, because a name refers to the dravya (a unique person or thing).

[2]:

In Sāhitya-darpaṇa (2.4),Viśvanātha Kavirāja avoids confusion by replacing the term saṃjñā with dravya. The difference between dravya and vyakti is that dravya is a characteristic of vyakti. An individual (vyakti) is a unique entity (dravya). The purpose of making this difference is simply to set a limitation in the assignation of a name (saṃjñā): If a name were assigned to an individual (vyakti) without referring to the fact that the individual is a unique entity (dravya), then any other individual could be called by that name.

[3]:

At first, a word refers to one of these four: jāti, guṇa, kriyā, or saṃjñā. After that, the vyakti (the individual person, thing, or action) is automatically referred to, by the process called ākṣepa (necessary connection) (2.12).

[4]:

For instance, in the sentence: gām ānaya, “Bring a cow,” by means of which the assignation of the meaning of the word go was made, the assignation pertains to the category (jāti) of cow, which is a characteristic of that cow. The assignation was not done in regard to that individual cow (vyakti). If the latter were true (i.e. the jāti would not be referred to), then a person who applies the notion of go to any other cow would be right, but by that logic one could also say that any other individual thing is called go, because the jāti is not referred to.

[5]:

The gist is that the color blue, for example, has different shades, yet it is not wrong to say “The sky is blue” and “The ocean is blue” although the same word blue is used in different shades of meaning. In this interpretation, only an individual blue color is meant, but there is no concomitant occurrence of the fault of discrepancy because in each example the specific blue color pertains to a specific thing. Moreover, Mammaṭa does not say “Nothing is irreproachable.” He only says that a difference is as if perceived: guṇa-kriyā-yadṛcchānāṃ vastuta eka-rūpāṇām apy āśraya-bhedād bheda iva lakṣyate (Kāvya-prakāśa 2.8).

[6]:

Here “the category (jāti) of Ḍittha” means the state of being Ḍittha throughout his life (Alaṅkāra-kaustubha 2.7) (Mahā-bhāṣya 5.1.119). Ḍittha is a fictitious name of a person, which is used by rhetoricians with respect to Patañjali, who invented that name in his enunciation of the theory (Mahā-bhāṣya 5.1.119).

[7]:

[8]:

[9]: