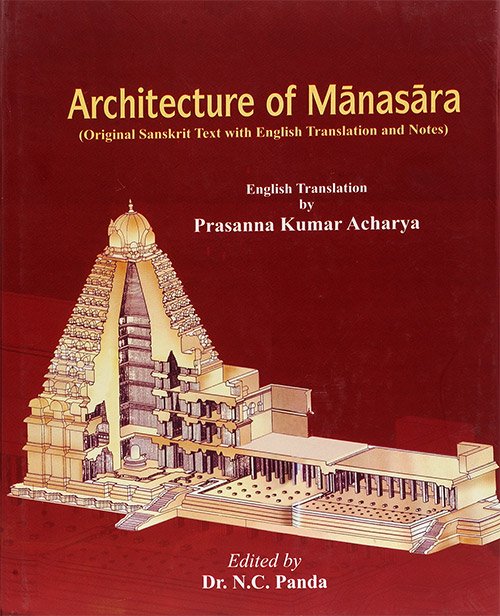

Manasara (English translation)

by Prasanna Kumar Acharya | 1933 | 201,051 words

This page describes “the qualifications of architects and the system of measurement” which is Chapter 2 of the Manasara (English translation): an encyclopedic work dealing with the science of Indian architecture and sculptures. The Manasara was originaly written in Sanskrit (in roughly 10,000 verses) and dates to the 5th century A.D. or earlier.

Chapter 2 - The Qualifications of Architects and the system of Measurement

[Full title: The Qualifications of Architects (śilpi-lakṣaṇa) and the system of Measurement (mānopakaraṇa)]

1. I shall (now) describe the qualifications of architects (and) the system of measurement in order.

2. From the supreme Śiva (emanate) the creator Brahmā and also Indra.

3-4. That He is the great architect of the universe is proclaimed by God Himself. It is He who as the architect of the universe creates the world again.

5. This Viśvakarman (the architect of the universe) is born with four faces like those of Brahmā and others.

6. I shall separately mention the four names (of the faces) beginning with the eastern one.

7-9. Of these, the eastern lace is known by the name of Viśvabhū (progenitor of the universe), the southern face (is known by the name of) Viśvavit (knower of the universe), and similarly, the northern face is named Viśvastha (resident in the universe), (and) the western face (bears) the designation of Viśva-sraṣṭar [Viśvasraṣṭra/Viśvasraṣṭrā=Viśvasraṣṭṛ?] (creator of the universe). Thus (is named) the fourfold face.

10. From these (faces) four (families of) architects were first born.

11-12. From the eastern face was born Viśvakarmā, from the southern face Maya, from the northern face Tvaṣṭar [Tvaṣṭra=Tvaṣṭṛ?], while (the one born) from the western face is known as Manu.

13-16. Viśvakarmā married the daughter of Indra, and then in order Maya married the daughter of Surendra, afterwards Tvaṣṭar married the daughter of Vaiśravaṇa, while, the fourth (one), Manu, married the daughter of Nala.

17. The son of him bearing the name of Viśvakarman is called sthapati (master-builder).

18. Maya’s son is known as sūtra-grāhin (draftsman),

19. The son of the sage Tvaṣṭar is called vardhaki (designer).

20. Manu’s son is takṣaka (carpenter). These are four (architects), (namely), the sthapati and the others.

21. Among these four the sthapati is known as the guru (guide) of the other three;

22. The sūtragrāhin is aow-a-days said to be the guru (guide) of the (next) two among the four.

23. The guru (guide) of the takṣaka is known by the name of vardhaki,

24-25. The sthapati knows all the śāstras (branches of knowledge). The sūtragrāhin holds the śūtra [sūtra?] (measuring-string). The vardhaki is well-versed in the work of measurement. The takṣaka is so called because of his carpentering.

26-27. The sthapati is capable of directing, knows the Vedas, (and) is deeply learned in the śāstra (science of architecture). The sthapati is so called because he is the director-general (of architecture, i.e., the master-builder).

28-29. Under the directions of the sthapati the sūtragrāhin and all the others always carefully carry out the building-work in accordance with the rules of the science (of architecture).

30. The four classes, consisting of the sthapati and the others, are distinguished by the architects.

31. The sthapati ia known, to be endowed with the qualifications of an ācārya (director).

32. The sūtragrāhin (also) knows the Vedic literature, is well-versed in the śāstras (branches of knowledge), and is an expert in (architectural) drawing.

33. The vardhaki also knows the Vedic literature, capable of (correctly) judging (architectural matters), and is an expert in the work of painting,

34-35. The takṣaka knows well (his) work (carpentry), is sociable, helpful (to his colleagues), faithful to his friends, and kind in nature. The Vedic literature should also be studied (by him). (Thus) all (his) qualifications are described.

36-38. In this (building-work) nowhere in the world success can be achieved without the help of the architect and the guide; therefore, with the help of these (architects) (the building-work) should be carried out, because without following this instruction no one can successfully attain fruition and the final object (i.e, completion).

39. The qualifications of the architects have been (thus) described; the system of measurement will (now) be elaborated.

40-41. What is perceptible to the eye of the sages is called a paramāṇu (atom), and eight times this is known as a rathadhūli (lit. ear-dust, molecule).

42. Eight of the molecules combined are what is known as a vālāgra (hair-end).

43. Eight hair-ends joined together make what is called a likṣā (nit).

44. Eight aits combined together are called a yūka (louse).

45. Eight lice together are called a yava (barley-corn).

46. Eight barley-corns combined together make what is called an aṅgula (finger-breadth.).,

47-48. Each of those (modos of measurement) is said to be of throe kinds, eepecially with, regard to (the increment of) yava-measurement. With six, seven, and eight barley-corns are (distinguished respectively) the smallest, the intermediate, and the largest yam measurements.

49. Twelve aṅgulas together are called one vitasti (span).

50. Two vitastis make a kiṣku (small cubit) and an aṅgula added to them, it is a prājāpatya (cubit).

51. A cubit of twenty-six aṅgulas is known as dhanurmuṣṭi.

52. A cubit of twenty-seven aṅgulas is called a dhanurgraha.

53. Four dhanurmuṣṭi cubits make a daṇḍa and eight daṇḍas make one rajju.

54. The kiṣku cubit is used in measuring conveyances and couches.

55. The prājāpatya cubit is used in measuring all kinds of mansions.

56. And the edifices are measured in what is (called) the dhanurmuṣṭi cubit.

57. Measurement of villages and such other objects should be carried out in the dhanur-graha, cubit.

58. But the measurement in kiṣku cubit may otherwise be used in measuring all the objects.

59-60. Samī (Acacia suma), śāka (Ocimim sanctum), cāpa (? bow-tree), khadira (Acacia catechu), tamālaka (Xanthochymus pictorius), kṣīriṇī (milk-tree) and tindinī (tamarind tree) are known as the kinds of wood for the yard-stick.

61-63. After selecting the wood (for the yard-stick) it should be dipped into water for three months. After having been washed it should be taken out (of water) and be split by the carpenter. The sapped part of that hewn timber should be shaped into a (solid) foursided (piece),

64-65. It should be one cubit long, one aṅgula (three-fourths inch) broad, and its thickness is stated to be a half aṅgula. The yard-stick (lit. cubit-measure) should be accurately marked,

66-67. Either kramuka (betel nut tree) or veṇu (bamboo) is stated to be (fit as) the timber for the (measuring) rod (which should be) neither bent, nor broken, nor porous but smooth.

68. Viṣṇu is stated to be the tutelary god of (the wood for) both the yard-stick and the (measuring) rod.

69-71. The rope-marker should make the rope (rajju) with the split husk of cocoanut, with the kuśa-grass (Poa cynosuroides), the bark of the banyan tree, silk cotton, and kiṃśuka (Butea frondosa) thread, bark of the palm troo, and ketaka (Pandanus odoratissimus), or with any other suitable bark.

72. Measuring sidewise, the width of the measuring rope should be one aṅgula.

73-74. Tho rope should be made free from knots and three-fold for (measuring the architectural objects of) the Gods, Brahmins (earthly-gods) ami Kings (Kṣatriyas), two-fold for (those of) the Vaiśyas, and of single-fold for (those of) the Śūdras.

75. Vāsukī (serpent-god) is the presiding deity of the (measuring) rope, and Brahmā is known as the presiding deity of measurement.

76-77. Thus ascertaining the yard-stick (cubit), the rope and similarly, the measuring rod, and remembering those presiding deities the vardhaki should carry out the measurement (of an object).

78. Thus measured the architectural objects are attended with success.

79. One who does what is not proscribed becomes recipient of scanty result.

80. The architect should, therefore, avoid (the unprescribed things) but he should thoroughly do that (which has boon prescribed):

Thus in the Mānasāra, the science of architecture, the second chapter, entitled: “The description of the details of measurement.”