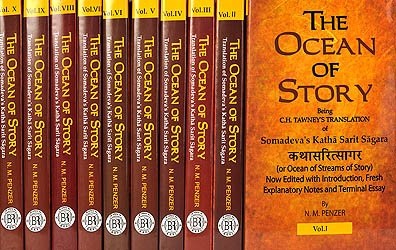

Kathasaritsagara (the Ocean of Story)

by Somadeva | 1924 | 1,023,469 words | ISBN-13: 9789350501351

This is the English translation of the Kathasaritsagara written by Somadeva around 1070. The principle story line revolves around prince Naravāhanadatta and his quest to become the emperor of the Vidhyādharas (‘celestial beings’). The work is one of the adoptations of the now lost Bṛhatkathā, a great Indian epic tale said to have been composed by ...

Chapter LIII

[M] (main story line continued) THEN, on the next day, Naravāhanadatta’s friend Marubhūti said to him, when he was in the company of Alaṅkāravatī:

“See, King, this miserable dependent[1] of yours remains clothed with one garment of leather, with matted hair, thin and dirty, and never leaves the royal gate, day or night, in cold or heat; so why do you not show him favour at last? For it is better that a little should be given in time, than much when it is too late; so have mercy on him before he dies.”

When Gomukha heard this, he said:

“Marubhūti speaks well, but you, King, are not the least in fault in this matter; for until a suitor’s guilt, which stands in his way, is removed, a king, even though disposed to give, cannot give; but when a man’s guilt is effaced a king gives, though strenuously dissuaded from doing so; this depends upon works in a previous state of existence. And à propos of this I will tell you, O King, the story of Lakṣadatta the king, and Labdhadatta the dependent. Listen.

69. Story of King Lakṣadatta and his Dependent Labdhadatta [2]

There was on the earth a city named Lakṣapura. In it there lived a king named Lakṣadatta, chief of generous men. He never knew how to give a petitioner less than a lac of coins, but he gave five lacs to anyone with whom he conversed. As for the man with whom he was pleased, he lifted him out of poverty; for this reason his name was called Lakṣadatta. A certain dependent named Labdhadatta stood day and night at his gate, with a piece of leather for his only loin-rag. He had matted hair, and he never left the king’s gate for a second, day or night, in cold, rain or heat, and the king saw him there.

And though he remained there long in misery, the king did not give him anything, though he was generous and compassionate.

Then one day the king went to a forest to hunt, and his dependent followed him with a staff in his hand. There, while the king, seated on an elephant, armed with a bow, and followed by his army, slew tigers, bears and deer, with showers of arrows, his dependent, going in front of him, alone on foot, slew with his staff many boars and deer. When the king saw his bravery, he thought in his heart, “It is wonderful that this man should be such a hero,”

but he did not give him anything. And the king, when he had finished his hunting, returned home to his city to enjoy himself, but that dependent stood at his palace gate as before.

Once on a time Lakṣadatta went out to conquer a neighbouring king of the same family, and he had a terrible battle. And in the battle the dependent struck down in front of him many enemies, with blows from the end of his strong staff of acacia wood. And the king, after conquering his enemies, returned to his own city, and though he had seen the valour of his dependent, he gave him nothing. In this condition the dependent Labdhadatta remained, and many years passed over his head, while he supported himself with difficulty.

And when the sixth year had come King Lakṣadatta happened to see him one day, and feeling pity for him, reflected:

“Though he has been long afflicted I have not as yet given him anything, so why should I not give him something in a disguised form, and so find out whether the guilt of this poor man has been effaced or not, and whether even now Fortune will grant him a sight of her or not?”

Thus reflecting, the king deliberately entered his treasury and filled a citron with jewels, as if it were a casket. And he held an assembly of all his subjects, having appointed a meeting outside his palace, and there entered the assembly all his citizens, chiefs and ministers. And when the dependent entered among them the king said to him with an affectionate voice: “Come here.” Then the dependent, on hearing this, was delighted, and coming near, he sat in front of the king.

Then the king said to him:

“Utter some composition of your own.”

Then the dependent recited the following Āryā verse:

“Fortune ever replenishes the full man, as all the streams replenish the sea, but she never even comes within the range of the eyes of the poor.”

When the king had heard this, and had made him recite it again, he was pleased, and gave him the citron full of valuable jewels.

And the people said:

“This king puts a stop to the poverty of everyone with whom he is pleased; so this dependent is to be pitied, since this very king, though pleased with him, after summoning him politely, has given him nothing but this citron. A wishing-tree, in the case of ill-starred men, often becomes a palāśa-tree”[3]

These were the words which all in the assembly said to one another in their despondency when they saw that, for they did not know the truth.

But the dependent went out with the citron in his hand, and when he was in a state of despondency a mendicant came before him. And that mendicant, named Rājavandin, seeing that the citron was a fine one, obtained it from that dependent by giving him a garment.

And then the mendicant entered the assembly and gave that fruit to the king, and the king, recognising it, said to that hermit[4]:

“Where, reverend sir, did you procure this citron?”

Then he told the king that the dependent had given it to him. Then the king was grieved and astonished, reflecting that his guilt was not expiated even now. The King Lakṣadatta took the citron, rose up from the assembly and performed the duties of the day. And the dependent sold the garment, and, after he had eaten and drunk, remained at his usual post at the king’s gate.

And on the second day the king held a general assembly, and everybody appeared at it again, citizens and all. And the king, seeing that the dependent had entered the assembly, called him as before and made him sit near him. And after making him again recite that very same Āryā verse, being pleased, he gave him that very same citron with jewels concealed in it.

And all there thought with astonishment:

“Ah! this is the second time that our master is pleased with him without his gaining by it.”

And the dependent, in despondency, took the citron in his hand, and thinking that the king’s good-will had again been barren of results, went out. At that very moment a certain official met him, who was about to enter that assembly, wishing to see the king. He, when he saw that citron, took a fancy to it, and, regarding the omen,[5] procured it from the dependent by giving him a pair of garments. And entering the king’s court he fell at the feet of the sovereign, and first gave him the citron, and then another present of his own. And when the king recognised the fruit he asked the official where he got it, and he replied: “From the dependent.” And the king, thinking in his heart that Fortune would not even now give the dependent a sight of her, was exceedingly sad. And he rose up from the assembly with that citron, and the dependent went to the market with the pair of garments he had got. And by selling one garment he procured meat and drink, and tearing the other in half he made two of it.

Then on the third day also the king held a general assembly, and all the subjects entered, as before, and when the dependent entered, the king gave him the same citron again, after calling him and making him recite the Āryā verse. Then all were astonished, and the dependent went out and gave that citron to the king’s mistress. And she, like a moving creeper of the tree of the king’s regard, gave him gold, which was, so to speak, the flower, the harbinger of the fruit. The dependent sold it and enjoyed himself that day, and the king’s mistress went into his presence. And she gave him that citron, which was large and fine, and he, recognising it, asked her whence she procured it.

Then she said: “The dependent gave it me.” Hearing that, the king thought:

“Fortune has not yet looked favourably upon him; his merit in a former life must have been slight, since he does not know that my favour is never barren of results. And so these splendid jewels come back to me again and again.”

Thus the king reflected, and he took that citron and put it away safely, and rose up and performed the duties of the day.

And on the fourth day the king held an assembly in the same way, and it was filled with all his subjects, feudatories, ministers and all. And the dependent came there again, and again the king made him sit in front of him, and when he bowed before him the king made him recite the Āryā verse, and gave him the citron; and when the dependent had half got hold of it he suddenly let it go, and the citron fell on the ground and broke in half. And as the joining of the citron, which kept it together, was broken, there rolled out of it many valuable jewels, illuminating that place of assembly.

All the people, when they saw it, said:

“Ah! we were deluded and mistaken, as we did not know the real state of the case, but such is the nature of the king’s favour.”

When the king heard that, he said:

“By this artifice I endeavoured to ascertain whether Fortune would now look on him or not. But for three days his guilt was not effaced; now it is effaced, and for that reason Fortune has now granted him a sight of herself.”

After the king had said this, he gave the dependent those jewels, and also villages, elephants, horses and gold, and made him a feudal chief. And he rose up from that assembly, in which the people applauded, and went to bathe; and that dependent too, having obtained his ends, went to his own dwelling.

[M] (main story line continued)

“So true is it that, until a servant’s guilt is effaced, he cannot obtain the favour of his master, even by going through hundreds of hardships.”

When Gomukha, the prime minister, had told this tale, he again said to his master Naravāhanadatta:

“So, King, I know that even now the guilt of that dependent of yours is not expiated, since even now you are not pleased with him.”

When the son of the King of Vatsa heard this speech of Gomukha’s, he said: “Ha! Good!.” And he immediately gave to his own dependent, who was named Kārpaṭika, a number of villages, elephants and horses, a crore of gold pieces, and excellent garments, and ornaments. Then that dependent, who had attained prosperity, became like a king. How can the attendance on a grateful king, who has excellent courtiers, be void of fruit?

When Naravāhanadatta was thus employed there came one day, to take service with him, a young Brāhman from the Deccan, named Pralambabāhu. That hero said to the prince:

“I have come to your feet, my sovereign, attracted by your renown, and I on foot will never leave your company for a step, as long as you travel on the earth with elephants, horses and chariots; but in the air I cannot go. I say this because it is rumoured that my lord will one day be Emperor of the Vidyādharas. A hundred gold pieces should be given to me every day as salary.”

When that Brāhman, who was really of incomparable might, said this, Naravāhanadatta gave him this salary. And thereupon Gomukha said:

“My lord, kings have such servants. A propos of this, hear this story.”

70. Story of the Brāhman Vīravara [6]

There is in this country a great and splendid city of the name of Vikramapura. In it there lived long ago a king named Vikramatuṅga. He was distinguished for statesmanship, and though his sword was sharp, his rod of justice was not so; and he was always intent on righteousness, but not on women, hunting, and so forth. And while he was king the only atoms of wickedness were the atoms of earth in the dust; the only departure from virtue was the loosing of arrows from the string; the only straying from justice was the wandering of sheep in the folds of the keepers of cattle.[7]

Once on a time a heroic and handsome Brāhman, from the country of Mālava, named Vīravara, came there to take service under that king. He had a wife named Dharmavatī, a daughter named Vīravatī, and a son named Sattvavara; these three constituted his family; and his attendants consisted of another three: at his hip a dagger, in one hand a sword, and in the other a polished shield. Though he had such a small following, he demanded from that king five hundred dīnārs[8] every day by way of salary. And the king gave him that salary, perceiving his courage, and thinking to himself: “I will make trial of his excellence.” And the king set spies on him, to find out what this man, with only two arms, would do with so many dīnārs.

And Vīravara, every day, gave his wife a hundred of those dīnārs for food and other purposes; and with another hundred he bought clothes, and garlands, and so on; and he appointed a third hundred, after bathing, for the worship of Viṣṇu and Śiva; and the remaining two hundred he gave to Brāhmans, the poor and so on; and so he expended every day the whole five hundred. And he stood at the palace gate of the king for the first half of the day, and after he had performed his daily prayers and other duties he came back and remained there at night also. The spies reported to the king continually that daily practice of his, and then the king, being satisfied, ordered those spies to desist from observing him. And Vīravara remained day and night at the gate of the king’s palace, sword in hand, excepting only the time set apart for bathing and matters of that kind.

Then there came a collection of clouds, bellowing terribly, as if determined to conquer that Vīravara, being impatient of his valour. And then, though the cloud rained a terrible arrow-shower of drops, Vīravara stood like a column and did not leave the palace gate. And the King Vikramatuṅga, having beheld him from the palace in this position, went up to the roof of the palace at night to try him again.

And he called out from above: “Who waits at the palace gate?”

And Vīravara, when he heard that, answered: “I am here.”

The king, hearing this, thought:

“Surely this brave man deserves high rank, for he does not leave the palace gate though such a cloud is raining.”

While engaged in those reflections the king heard a woman weeping bitterly in the distance, and he thought:

“There is not an afflicted person in my dominions, so why does she weep?”

Thereupon he said to Vīravara:

“Hark, Vīravara, there is some woman weeping at some distance from this place, so go and find out who she is and what is her sorrow.”

When Vīravara heard that, he set out, brandishing his sword, with his dagger at his side. Then the king, seeing that he had set out when such a cloud was blazing with lightning, and when the interval between heaven and earth[9] was full of descending drops of rain, being moved with curiosity and pity, came down from the roof of his palace and set out behind him, sword in hand, unobserved.

And Vīravara, going in the direction of the wailing,[10] followed unperceived by the king, reached a lake outside the city.

And he saw a woman lamenting in the midst of it:

“Ah, lord! Ah, merciful one! Ah, hero! How shall I exist abandoned by thee?”

He asked her:

“Who are you, and what lord do you lament?”

Then she said:

“My son, know that I am this earth. At present Vikramatuṅga is my righteous lord, and his death will certainly take place on the third day from now. And how shall I obtain such a lord again? For with divine foresight I behold the good and evil to come, as Suprabha, the son of a god, did when in heaven.

70a. Suprabha and his Escape from Destiny

For he, possessing divine foresight, foresaw that in seven days he would fall from heaven on account of the exhaustion of his merits and be conceived in the body of a sow. Then that son of a god, reflecting on the misery of dwelling in the body of a sow, regretted with himself those heavenly enjoyments:

“Alas for heaven! Alas for the Apsarases! Alas for the arbours of Nandana! Alas! How shall I live in the body of a sow, and after that in the mire?”

When the king of the gods heard him indulging in these lamentations he came to him and questioned him, and that son of a god told him the cause of his grief.

Then Indra said to him:

“Listen, there is a way out of this difficulty open to you. Have recourse to Śiva as a protector, exclaiming: ‘Om![11] Honour to Śiva!’ If you resort to him as a protector you shall escape from your guilt and obtain merit, so that you shall not be born in the body of a pig nor fall from heaven.”

When the king of the gods said this to Suprabha he followed his advice, and exclaiming, “Om! Honour to Śiva!” he fled to Śiva as an asylum. After remaining wholly intent on him for six days, he not only by his favour escaped being sent into the body of a pig, but went to an abode of bliss higher than Svarga. And on the seventh day, when Indra, not seeing him in heaven, looked about, he found he had gone to another and a superior world.

70. Story of the Brāhman Vīravara

“As Suprabha lamented, beholding pollution impending, so I lament, beholding the impending death of the king.”

When Earth[12] said this, Vīravara answered her:

“If there is any expedient for rescuing this king, as there was an expedient for rescuing Suprabha in accordance with the advice of Indra, pray tell it me.”

When Earth was thus addressed by Vīravara, she answered him:

“There is an expedient in this case, and it is in your hands.”

When the Brāhman Vīravara heard this, he said joyfully[13]:

“Then tell me, goddess, quickly; if my lord can be benefited by the sacrifice of my life, or of my son or wife, my birth is not wasted.”

When Vīravara said this, Earth answered him:

“There is here an image of Durgā near the palace; if you offer to that image your son Sattvavara, then the king will live, but there is no other expedient for saving his life.”

When the resolute Vīravara heard this speech of the goddess Earth, he said:

“I will go, lady, and do it immediately.”

And Earth said:

“What other man is so devoted to his lord? Go, and prosper.”

And the king, who followed him, heard all.

Then Vīravara went quickly to his house that night, and the king followed him unobserved. There he woke up his wife Dharmavatī and told her that, by the counsel of the goddess Earth, he must offer up his son for the sake of the king.

She, when she heard it, said:

“We must certainly do what is for the advantage of the king; so wake up our son and tell him.”

Then Vīravara woke up his son and told him all that the goddess Earth had told him, as being for the interest of the king, down to the necessity of his own sacrifice. When the child Sattvavara heard this, he, being rightly named, said to his father[14]:

“Am I not fortunate, my father, in that my life can profit the king? I must requite him for his food which I have eaten; so take me and sacrifice me to the goddess for his sake.”

When the boy Sattvavara said this, Vīravara answered him undismayed:

“In truth you are my own son.”

When King Vikramatuṅga, who was standing outside, heard this, he said to himself:

“Ah! the members of this family are all equally brave.”

Then Vīravara took that son Sattvavara on his shoulder, and his wife Dharmavatī took his daughter Vīravatī on her back, and the two went to the temple of Durgā by night.

And the King Vikramatuṅga followed them, carefully concealing himself. When they reached the temple, Sattvavara was put down by his father from his shoulder, and, though he was a boy, being a store-house of courage, he bowed before the goddess, and addressed this petition to her:

“Goddess, may our lord’s life be saved by the offering of my head! And may the King Vikramatuṅga rule the earth without an enemy to oppose him !”

When the boy said this, Vīravara exclaimed: “Bravo, my son!” And drawing his sword he cut off his son’s head and offered it to the goddess Durgā, saying: “May the king be prosperous!”

Those who are devoted to their master grudge them neither their sons’ lives nor their own.

Then a voice was heard from heaven, saying:

“Bravo, Vīravara! You have bestowed life on your master by sacrificing even the life of your son.”

Then, while the king was seeing and hearing with great astonishment all that went on, the daughter of Vīravara, named Vīravatī, who was a mere girl, came up to the head of her slain brother, and embraced it, and kissed it, and crying out, “Alas! my brother!” died of a broken heart.

When Vīravara’s wife Dharmavatī saw that her daughter also was dead, in her grief she clasped her hands together and said to Vīravara:

“We have now ensured the prosperity of the king, so permit me to enter the fire with my two dead children. Since my infant daughter, though too young to understand anything, has died out of grief for her brother, what is the use of my life, my two children being dead?”

When she spoke with this settled purpose, Vīravara said to her:

“Do so; what can I say against it? For, blameless one, there remains no happiness for you in a world which will be all filled for you with grief for your two children; so wait a moment while I prepare the funeral pyre.”

Having said this, he constructed a pyre with some wood that was lying there to make the fence of the enclosure of the goddess’s temple, and put the corpses of his children upon it, and lit a fire under it, so that it was enveloped in flames.

Then his virtuous wife Dharmavatī fell at his feet, and exclaiming,

“May you, my husband, be my lord in my next birth, and may prosperity befall the king!”

she leapt into that burning pyre, with its hair of flame, as gladly as into a cool lake. And King Vikramatuṅga, who was standing by unperceived, remained fixed in thought as to how he could possibly recompense them.

Then Vīravara, of resolute soul, reflected:

“I have accomplished my duty to my master, for a divine voice was heard audibly, and so I have requited him for the food which I have eaten; but now that I have lost all the dear family I had to support[15] it is not meet that I should live alone, supporting myself only, so why should I not propitiate this goddess Durgā by offering up myself?”

Vīravara, firm in virtue, having formed this determination, first approached, with a hymn of praise, that goddess Durgā, the granter of boons.

“Honour to thee, O great goddess, that givest security to thy votaries; rescue me, plunged in the mire of the world, that appeal to thee for protection. Thou art the principle of life in creatures; by thee this world moves. In the beginning of creation Śiva beheld thee self-produced, blazing and illuminating the world with brightness hard to behold, like ten million orbs of fiery suddenly produced infant suns rising at once, filling the whole horizon with the circle of thy arms, bearing a sword, a club, a bow, arrows and a spear.

And thou wast praised by that god Śiva in the following words:

‘Hail to thee, Caṇḍī, Cāmuṇḍā, Maṅgalā, Tripurā, Jayā, Ekānaṃśā, Śivā, Durgā, Nārāyaṇī, Sarasvatī, Bhadrakālī, Mahālakṣmī, Siddhā, slayer of Ruru ! Thou art Gāyatrī, Mahārājñī, Revatī, and the dweller in the Vindhya hills; thou art Umā and Kātyāyanī, and the dweller in Kailāsa, the mountain of Śiva.’

When Skanda, and Vasiṣṭha, and Brahmā, and the others heard thee praised, under these and other titles, by Śiva well skilled in praising, they also praised thee. And by praising thee, O adorable one, immortals, Ṛṣis and men obtained, and do now obtain, boons above their desire. So be favourable to me, O bestower of boons, and do thou also receive this tribute of the sacrifice of my body, and may prosperity befall my lord the king !”

After saying this, he was preparing to cut off his own head,[16] but a bodiless voice was heard at that moment from the air:

“Do not act rashly, my son, for I am well pleased with this courage of thine; so crave from me a boon that thou desirest.”

When Vīravara heard that, he said:

“If thou art pleased, goddess, then may King Vikramatuṅga live another hundred years. And may my wife and children return to life.”

When he craved this boon there again sounded from the air the words: “So be it!” And immediately the three, Dharmavatī, Sattvavara and Vīravatī, rose up with unwounded bodies. Then Vīravara was delighted, and took home to his house all those who had been thus restored to life by the favour of the goddess, and returned to the king’s gate.

But the king, having beheld all this with joy and astonishment, went and again ascended the roof of his palace unobserved.

And he cried out from above:

“Who is on guard at the palace gate?”

When Vīravara, who was below, heard that, he answered:

“I am here; and I went to discover that woman, but she vanished somewhere as soon as I saw her, like a goddess.”

When King Vikramatuṅga heard this, as he had seen the whole transaction, which was exceedingly wonderful, he reflected with himself alone in the night:

“Oh! surely this man is an unheard-of marvel of heroism to perform such an exceedingly meritorious action and not to give any account of it, The sea, though deep and broad, and full of great monsters,[17] does not vie with this man, who is firm even in the shock of a mighty tempest. What return can I make to him, who secretly redeemed my life this night by the sacrifice of his son and wife?”

Thus reflecting, the king descended from the roof of the palace, and went into his private apartments, and passed that night in smiling. And in the morning, when Vīravara was present in the great assembly, he related his wonderful exploit that night. Then all praised Vīravara, and the king conferred on him and his son a turban of honour. And he gave him many domains, horses, jewels and elephants, and ten crores of gold pieces, and a salary sixty times as great as before. And immediately the Brāhman Vīravara became equal to a king, with a lofty umbrella,[18] being prosperous, himself and his family.

[M] (main story line continued) When the minister Gomukha had told this tale, he again said to Naravāhanadatta, summing up the subject:

“Thus, King, do sovereigns, by their merit in a previous life, sometimes fall in with exceptionally heroic servants, who, in their nobility of soul, abandoning regard for their lives and all other possessions for the sake of their master, conquer completely the two worlds. And Pralambabāhu, this lately arrived heroic Brāhman servant of yours, is seen to be such, of settled virtue and character, a man in whom the quality of goodness is ever on the increase.”

When the noble-minded Prince Naravāhanadatta heard this from his minister, the mighty-minded Gomukha, he felt unsurpassed satisfaction in his heart.

[Additional note: on fate or destiny]

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

The word in the original is kārpaṭika. Böhtlingk and Roth explain it in this passage as “ein im Dienste eines Fürsten stehender Bettler.” It appears from Taraṅga 81 that a.poor man became a kārpaṭika by tearing a karpaṭa, a ragged garment, in a king’s presence. The business of a kārpaṭika seems to have been to do a service without getting anything for it.

[2]:

For a note on this story see the end of this chapter.—n.m.p.

[3]:

There is a pun here. The word palāśa also means “cruel,” “unmerciful.”

[4]:

The word used shows that he was probably a Buddhist mendicant.

[5]:

Fresh fruit and flowers are both lucky omens, and are included in Thurston’s and Enthoven’s lists. See my note on p. 122n1 of this volume.— n.m.p.

[6]:

This story is found in the Hitopadeśa, p. 89 of Johnson’s translation.

[7]:

These two lines are an elaborate pun—ku = “evil,” and also “earth,” guṇa = “virtue,” and also “string,” avichāra = “injustice,” also “the movement of sheep.”——Cf. the punning verse in the Kathākoça, p. 37, where “stick” also means “punishment,” and “the pressure of hands” is also “oppressive taxes”:

“In this city sticks were connected only with umbrellas, imprisonings with hair, and slaying of men was heard only in chess.

Holes were picked in necklaces only: and hands paid the tribute of pressure only in marriage.”

See also p. 204 of this volume.—n.m.p.

[8]:

See Vol. I, p. 63n1.—n.m.p.

[9]:

I follow the MS. in the Sanskrit College, which reads rodorandhre.

[10]:

Here with the Sanskrit College MS. I read ruditam for the unmetrical kranditam.——This is confirmed by the D. text.—n.m.p.

[11]:

For a detailed account of the mystic syllable Om, see A. B. Keith, “Om,” Hastings’ Ency. Rel. Eth., vol. ix, pp. 490-492.—n.m.p.

[12]:

The Earth Goddess in India is worshipped mainly in connection with agricultural seasons. Her name in Vedic times was Pṛthivī (see Ṛg-Veda, v, 84). She is usually worshipped in conjunction with her husband, Dyaus, the Sky-Father. Parjanya is also given as the consort of Prithivī. He is the Vedic god of ther ain-cloud. Mention should also be made of Bhūmi, the soil, to whom cakes and fruits are offered in certain villages. For further details see Crooke, op. cit., vol. i, p. 26 et seq., and ditto in “Dravidians (North India),” Hastings’ Ency. Rel. Eth., vol. v, pp. 5-7, where is traced the developing of the cult of the Earth-Mother into a general Mother-cult. See also R. E. Enthoven, Folk-Lore of Bombay, 1924, pp. 81-88.— N.m.p.

[13]:

I read dhṛṣyan — i.e. rejoicing, from hṛṣ.

[14]:

The word sattvavara here means “possessing pre-eminent virtue.”

[15]:

In śl, 163 (a) I read mama for mayā with the Sanskrit College MS.

[16]:

The story as told in Chapter LXXVIII is somewhat different from this.

[17]:

There is a pun in this word mahāsattva. It means “noble,” “good,” “virtuous,” and also “full of great monsters.”

[18]:

See Vol. II, Appendix II, pp. 263-272.—n.m.p.