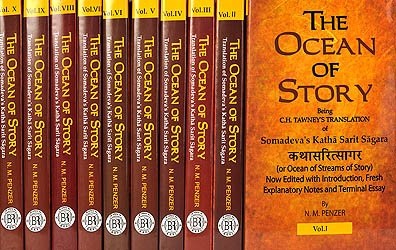

Kathasaritsagara (the Ocean of Story)

by Somadeva | 1924 | 1,023,469 words | ISBN-13: 9789350501351

This is the English translation of the Kathasaritsagara written by Somadeva around 1070. The principle story line revolves around prince Naravāhanadatta and his quest to become the emperor of the Vidhyādharas (‘celestial beings’). The work is one of the adoptations of the now lost Bṛhatkathā, a great Indian epic tale said to have been composed by ...

Chapter I

INVOCATION [1]

MAY the dark neck of Śiva,[2] which the God of Love[3] has, so to speak, surrounded with nooses in the form of the alluring looks of Pārvatī reclining on his bosom, assign to you prosperity.

May that Victor of Obstacles,[4] who, after sweeping away the stars with his trunk in the delirious joy of the evening dance, seems to create others with the spray issuing from his hissing[5] mouth, protect you.

After worshipping the Goddess of Speech, the lamp that illuminates countless objects,[6] I compose this collection which contains the pith of the Bṛhat-Kathā.

SUMMARY OF THE WORK

The first book in my collection is called Kāthapīṭha, then comes Kathāmukha, then the third book named Lāvāṇaka, then follows Naravāhanadattajanana, and then the book called Caturdārikā, and then Madanamañcukā, then the seventh book named Ratnaprabhā, and then the eighth book named Sūryaprabhā, then Alaṅkāravatī, then Saktiyaśas, and then the eleventh book called Velā, then comes Śaśāṅkavatī, and then Madirāvatī, then comes the book called Pañca, followed by Mahābhiṣeka, and then Suratamañjarī, then Padmāvatī, and then will follow the eighteenth book Viṣamaśīla.

This book is precisely on the model of that from which it is taken, there is not even the slightest deviation, only such language is selected as tends to abridge the prolixity of the work; the observance of propriety and natural connection, and the joining together of the portions of the poem so as not to interfere with the spirit of the stories, are as far as possible kept in view: I have not made this attempt through a desire of a reputation for ingenuity, but in order to facilitate the recollection of a multitude of various tales.

INTRODUCTION

[M] (main story line continued) [7] There is a mountain celebrated under the name of Himavat,[8] haunted by Kinnaras, Gandharvas, and Vidyādharas,[9] a very monarch of mighty hills, whose glory has attained such an eminence among mountains that Bhavānī, the mother of the three worlds, deigned to become his daughter; the northernmost summit thereof is a great peak named Kailāsa, which towers many thousand yojanas in the air,[10] and, as it were, laughs forth with its snowy gleams this boast:

“Mount Mandara[11] did not become white as mortar even when the ocean was churned with it, but I have become such without an effort.”

There dwells Maheśvara the beloved of Pārvatī, the chief of things animate and inanimate, attended upon by Gaṇas, Vidyādharas and Siddhas.[12] In the upstanding yellow tufts of his matted hair the new moon enjoys the delight of toucing the eastern mountain yellow in the evening twilight. When he drove his trident into the heart of Andhaka, the King of the Asuras,[12] though he was only one, the dart which that monarch had infixed in the heart of the three worlds was, strange to say, extracted. The image of his toe-nails being reflected in the crest-jewels of the gods and Asuras made them seem as if they had been presented with half moons by his favour.[13]

Once on a time that lord, the husband of Pārvatī, was gratified with praises by his wife, having gained confidence as she sat in secret with him; the moon-crested one, attentive to her praise and delighted, placed her on his lap, and said: “What can I do to please thee?” Then the daughter of the mountain spake:

“My lord, if thou art satisfied with me, then tell me some delightful story that is quite new.”

And Śiva said to her:

“What can there be in the world, my beloved, present, past, or future, that thou dost not know?”

Then that goddess, beloved of Śiva, importuned him eagerly because she was proud in soul on account of his affection.

Then Śiva, wishing to flatter her, began by telling her a very short story, referring to her own divine power.

“Once on a time[14] Brahmā and Nārāyaṇa,[15] roaming through the world in order to behold me, came to the foot of Himavat. Then they beheld there in front of them a great flame-liṅga[16]; in order to discover the end of it, one of them went up, and the other down; and when they could not find the end of it, they proceeded to propitiate me by means of austerities: and I appeared to them and bade them ask for some boon: hearing that Brahmā asked me to become his son; on that account he has ceased to be worthy of worship, disgraced by his overweening presumption:

“Then that god Nārāyaṇa craved a boon of me, saying: O revered one, may I become devoted to thy service! Then he became incarnate, and was born as mine in thy form; for thou art the same as Nārāyaṇa, the power of me all-powerful.

“Moreover thou wast my wife in a former birth.”

When Śiva had thus spoken, Pārvatī asked:

“How can I have been thy wife in a former birth?”

Then Śiva answered her:

“Long ago to the Prajāpati Dakṣa were born many daughters, and amongst them thou, O goddess! He gave thee in marriage to me, and the others to Dharma and the rest of the gods. Once on a time he invited all his sons-in-law to a sacrifice. But I alone was not included in the invitation; thereupon thou didst ask him to tell thee why thy husband was not invited. Then he uttered a speech which pierced thy ears like a poisoned needle: ‘Thy husband wears a necklace of skulls; how can he be invited to a sacrifice?’

“And then thou, my beloved, didst in anger abandon thy body, exclaiming: ‘This father of mine is a villain; what profit have I then in this carcass sprung from him?’

“And thereupon in wrath I destroyed that sacrifice of Dakṣa.[17]

“Then thou wast born as the daughter of the Mount of Snow, as the moon’s digit springs from the sea. Then recall how I came to the Himālaya in order to perform austerities; and thy father ordered thee to do me service as his guest: and there the God of Love, who had been sent by the gods in order that they might obtain from me a son to oppose Tāraka, was consumed,[18] when endeavouring to pierce me, having obtained a favourable opportunity. Then I was purchased by thee,[19] the enduring one, with severe austerities, and I accepted this proposal of thine, my beloved, in order that I might add this merit to my stock.[20] Thus it is clear that thou wast my wife in a former birth.

“What else shall I tell thee?”

Thus Śiva spake, and when he had ceased, the goddess, transported with wrath, exclaimed:

“Thou art a deceiver; thou wilt not tell me a pleasing tale even though I ask thee. Do I not know that thou worshippest Sandhyā, and bearest Gaṅgā[21] on thy head?”

Hearing that, Śiva proceeded to conciliate her, and promised to tell her a wonderful tale: then she dismissed her anger. She herself gave the order that no one was to enter where they were; Nandin[22] thereupon kept the door, and Śiva began to speak.

“The gods are supremely blessed, men are ever miserable, the actions of demigods are exceedingly charming, therefore I now proceed to relate to thee the history of the Vidyādharas.”

While Śiva was thus speaking to his consort, there arrived a favourite dependent of Śiva’s, Puṣpadanta, best of Gaṇas,[23] and his entrance was forbidden by Nandin, who was guarding the door. Curious to know why even he had been forbidden to enter at that time without any apparent reason, Puṣpadanta immediately entered, making use of his magic power attained by devotion to prevent his being seen, and when he had thus entered, he heard all the extraordinary and wonderful adventures of the seven Vidyādharas being narrated by the trident-bearing god, and having heard them, he in turn went and narrated them to his wife Jayā; for who can hide wealth or a secret from women? Jayā, the doorkeeper, being filled with wonder, went and recited it in the presence of Pārvatī. How can women be expected to restrain their speech? And then the daughter of the mountain flew into a passion, and said to her husband:

“Thou didst not tell me any extraordinary tale, for Jayā knows it also.”

Then the lord of Umā, perceiving the truth by profound meditation, thus spake:

“Puṣpadanta, employing the magic power of devotion, entered in where we were, and thus managed to hear it. He narrated it to Jayā; no one else knows it, my beloved.”

Having heard this, the goddess, exceedingly enraged, caused Puṣpadanta to be summoned, and cursed him, as he stood trembling before her, saying:

“Become a mortal, thou disobedient servant.”[24]

She cursed also the Gaṇa Mālyavān who presumed to intercede on his behalf. Then the two fell at her feet together with Jayā and entreated her to say when the curse would end, and the wife of Śiva slowly uttered this speech:

“A Yakṣa[25] named Supratīka, who has been made a Piśāca[25] by the curse of Kuvera, is residing in the Vindhya forest under the name of Kāṇabhūti. When thou shalt see him, and calling to mind thy origin, tell him this tale; then, Puṣpadanta, thou shalt be released from this curse. And when Mālyavān shall hear this tale from Kāṇabhūti, then Kāṇabhūti shall be released, and thou, Mālyavān, when thou hast published it abroad, shalt be free also.”

Having thus spoken, the daughter of the mountain ceased, and immediately these Gaṇas disappeared instantaneously like flashes of lightning. Then it came to pass in the course of time that Gaurī, full of pity, asked Śiva:

“My lord, where on the earth have those excellent Pramathas,[26] whom I cursed, been born?”

And the moon-diademed god answered:

“My beloved, Puṣpadanta has been born under the name of Vararuci in that great city which is called Kauśāmbī.[27] Moreover Mālyavān also has been born in the splendid city called Supratiṣṭhita under the name of Guṇāḍhya. This, O goddess, is what has befallen them.”

Having given her this information, with grief caused by recalling to mind the degradation of the servants that had always been obedient to him, that lord continued to dwell with his beloved in pleasure-arbours on the slopes of Mount Kailāsa, which were made of the branches of the Kalpa tree.[28]

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Compare with the introduction to The Thousand Nights and a Night, where Allah, Mohammed and his family are invoked. —n.m.p.

[2]:

His neck is dark because at the Churning of the Ocean poison came up and was swallowed by Śiva to save creation from disaster. The poison was held in his throat, hence he is called Nīlakaṇṭha (the blue-throated one). For the various accounts of the Churning of the Ocean see Mahābhārata, trans. by P. C. Roy, new edition, 1919, etc., Calcutta, vol. i, part i, pp. 55-57 (Book I, Sects. XVII, XVIII); Rāmāyaṇa, trans. by Carey and Marshman, Serampore, 1806, vol. 1, p. 41 et seq. (Book I, Sect. XXXVI); Viṣṇu Purāṇa, vol. i, H. H. Wilson’s Collected Works, 1864, p. 142 et seq. — n.m.p.

[3]:

I.e. Kāma, who here is simply the Hindu Cupid.— n.m.p.

[4]:

Dr Brockhaus explains this of Gaṇeśa: he is often associated with Śiva in the dance. So the poet invokes two gods, Śiva and Gaṇeśa, and one goddess, Sarasvatī, the goddess of speech and learning.—It is in his form as Vināyaka, or Vighneśa, that Gaṇeśa is the "Victor” or, better, “Remover of Obstacles.”— n.m.p.

[5]:

Sītkāra: a sound made by drawing in the breath, expressive of pleasure.

[6]:

There is a double meaning: padārtha also means words and their meanings.

[7]:

For explanation of the system of numbering the stories adopted throughout the work see my Introduction, pp. xxxviii and xxxix. —n.m.p.

[8]:

This is another form of Himālaya, “the abode of snow/’ Himagiri, Himādri, Himakūṭa, etc., are also found. The Greeks converted the name into Emodos and Imaos. Mt Kailāsa (the modern Kailās) is the highest peak of that portion of the Tibetan Himālayas lying to the north of Lake Mānasarowar. It is supposed to resemble a liṅga in shape, thus being an appropriate dwelling-place for Śiva and Pārvatī, who, as we see, appear under a variety of names. It is naturally a very sacred spot, and one to which numerous pilgrimages are made. —n.m.p.

[9]:

For details of these mythical beings see Appendix I at the end of this volume, pp. 197-207.— n.m.p.

[10]:

Possibly the meaning is that the mountain covers many thousand yojanas.—Either would be applicable (allowing, of course, for the usual Oriental exaggeration), for Kailāsa is 22,300 feet high and pilgrims take three weeks to circumambulate the base, prostrating themselves all the way. It is hard to say what distance a yojana represents. It is variously given as equal to four krośas (i.e. nine miles), eighteen miles and two and a half miles. For references see Macdonell and Keith’s Vedic Index, vol. ii, pp. 195, 196, and especially J. F. Fleet, “Imaginative Yojanas,” Journ. Roy. As. Soc., 1912 , pp. 229-239-— n.m.p.

[11]:

This mountain served the gods and Asuras as a churning-stick at the Churning of the Ocean for the recovery of the Amṛta and fourteen other precious things lost during the Deluge.

[12]:

For details of these mythical beings see Appendix I at the end of this volume. —n.m.p.

[13]:

Śiva himself wears a moon’s crescent.

[14]:

The Sanskrit word asti, meaning “thus it is” [lit. "there is”], is a common introduction to a tale.

[15]:

I.e. Viṣṇu. The name was also applied both to Brahmā and Gaṇeśa. —n.m.p.

[16]:

The liṅga, or phallus, is a favourite emblem of Śiva. Flame is one of his eight tanus, or forms-the others being ether, air, water, earth, sun, moon, and the sacrificing priest.—n.m.p.

[17]:

See the Bhāgavata Purāṇa for details of this story. It was translated by Burnouf, 4 vols., Paris, 1840-1847, 1884. —n.m.p.

[18]:

He was burnt up by the fire of Śiva’s eye.

[19]:

Compare Kālidāsa’s Kumāra Sambhava, Sarga v, line 86.

[20]:

Reading tatsañcayāya as one word. Dr Brockhaus omits the line. Professor E. B. Cowell would read priyam for priye.

[21]:

I.e. the Ganges, the most worshipped river in the world. It is supposed to have its origin in Śiva’s head, hence one of his many names is Gaṅgādhara, “Ganges-supporter.” For full details of the legend see R. T. H. Griffith, Rāmāyaṇa, Benares, 1895, p. 51 et seq.—N.M.P.

[22]:

One of Śiva’s favourite attendants-a sacred white bull on which he rides. Most of the paintings and statues of Śiva represent him in company with Nandin and Gaṇeśa.—n.m.p.

[23]:

Attendants of Śiva, presided over by Gaṇeśa-for details of these mythical beings see Appendix I at the end of this volume.—n.m.p.

[24]:

For the ativinīta of Dr Brockhaus’ text I read avinīta.

[25]:

For details of these mythical beings see Appendix I at the end of this volume.— n.m.p.

[26]:

Pramatha, an attendant on Śiva.

[27]:

Kauśāmbī succeeded Hastināpura as the capital of the emperors of India. Its precise site has not been ascertained, but it was probably somewhere in the Doāb, or, at any rate, not far from the west bank of the Yamunā, as it bordered upon Magadha and was not far from the Vindhya hills. It is said that there are ruins at Karāli, or Karāri, about fourteen miles from Allahābād on the western road, which may indicate the site of Kauśāmbī. It is possible also that the mounds of rubbish about Karrah may conceal some vestiges of the ancient capital—a circumstance rendered more probable by the inscription found there, which specifies Kaṭa as comprised within Kauśāmbī maṇḍala or the district of Kauśāmbī (note in Wilson’s Essays, p. 163).—As will be seen later (Chapter XXXII), the site of Kauśāmbī was discovered by General Cunningham. It is now called Kosam, and is on the Jumna (Yamunā), about thirty miles above Allahābād. —n.m.p.

[28]:

A tree of Indra’s Paradise that grants all desires.