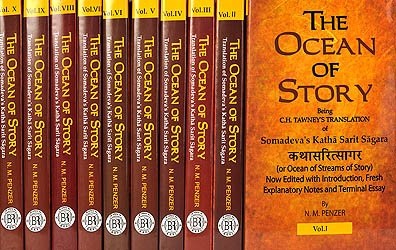

Kathasaritsagara (the Ocean of Story)

by Somadeva | 1924 | 1,023,469 words | ISBN-13: 9789350501351

This is the English translation of the Kathasaritsagara written by Somadeva around 1070. The principle story line revolves around prince Naravāhanadatta and his quest to become the emperor of the Vidhyādharas (‘celestial beings’). The work is one of the adoptations of the now lost Bṛhatkathā, a great Indian epic tale said to have been composed by ...

The history of sandalwood in ancient India

Note: this text is extracted from Book XII, chapter 95

On p. 99 of this chapter we read of the fair Anaṅgamañjarī being “white with sandalwood ointment.” Then again on p. 101 the love-sick Kamalākara vainly tries to quench the fire of love by lying on “a bed composed of lotus leaves moistened with sandalwood juice.” So too in the eleventh Vetāla one of the princesses has “sandalwood lotion applied to her body” (p. 11), while the third unfortunate lady “had sandalwood unguent and other remedies applied to her hands, in order to allay the pain” (p. 12). See also the references on pp. 30, 43, 53 and 72. We thus see that there appears to be two distinct uses to which sandalwood was put: as a face-cream for cooling and perfuming the skin, and as a medicinal application to relieve pain, burns, fever, etc.

It will be interesting to see how far this is confirmed by the historical evidence that exists with reference to sandalwood. All forms of the word as found in English (Sandal, Sandle, Sanders, Sandalwood) are derived from the Sanskrit chandana, “refreshing,” through the Persian sandal, chandal, the Arabic ṣandal, sandali-aswad, the Greek σάνταλον, σάνδαλον, Low Latin santalum, and French sandal, santal.

Sandalwood is the wood of the Santalum album, Linn., order Santalaceæ, which is a small evergreen tree native in the dry regions of South India (e.g. Western Ghats, Mysore and Coimbatore), while in Bombay, Poona, Gujarat, and several localities in Northern India it is chiefly a cultivated plant. The fragrance for which the wood is so prized depends on the presence of essential oil, situated chiefly in the dark central wood of the tree. It is the roots which yield the largest quantity and finest quality oil. It is pale yellow in colour, transparent, with a resinous taste and a peculiarly fragrant and penetrating odour. The outer parts of old trunks and young trees are almost entirely without scent, hence the sandal-cutters carefully remove the outer and generally lighter portion of the wood, which they term the “sap.” The heartwood is cut into small chips, and distillation is slowly carried on for ten days, at the end of which period the whole of the oil is extracted.

According to one authority 100 parts of sandalwood yield, upon distillation with steam, 1-25 to 2-8 parts of the essential oil (Watt, Economic Products of India, vol. vi, pt. ii, p. 464). Another author (Seemann, Intellectual Observer, vol. iv, p. 74) states that a pound of wood yields about two drachms of oil. In Hindu medical works sandalwood is described as bitter, cooling, astringent, and useful in biliousness, vomiting, fever, thirst and heat of the body (Dutt, Materia Medica of the Hindus, p. 225 of the 1877 edition). The wood ground up with water to the consistence of paste is a common application among the natives to erysipelous and local inflammations, to the temples in fevers, and to allay heat in cutaneous diseases. In remittent fevers it acts as a diaphoretic (Drury, Useful Plants of India, p. 383). The paste is also used for painting the body after bathing, and is employed for making the Shardana, or caste-marks, especially in Southern India. Sandalwood powder mixed with coconut-water is used in bathing to cool the body, and is especially efficient in the case of headache, prickly heat, etc. Watt (op. cit., p. 465) gives several references to accounts of the effective use of the oil in venereal diseases.

We pass on to the value of the wood for other domestic and religious purposes. In these cases it is the perfume of the distilled oil which is so important. As mentioned above, the oil from the roots is the finest, although an oil is expressed from the seeds, but this is a thick, viscid oil used only by the poorer classes in lamps. The essential oil constitutes the basis of the majority of attars distilled in India, and, mixed with pure alcohol, forms the perfumers Extrait de bois de Santal. In order to sweeten it for use on the handkerchief a slight addition of rose is required. It mixes well with soap. With charcoal and a little nitre it forms sandal pastilles for perfuming apartments, but much of the odour is lost in the preparation (Seemann, op. cit.t P- 74)

The wood is used chiefly in the carving industry—boxes, cabinets, worktables, walking-sticks, fans, picture-frames, etc., being some of the more usual articles so made. The Kanara district is the chief home of the sandalwood-carving industry. For the possible identification of the Algum or Almug trees of 1 Kings x, 11, 12, and 2 Chronicles ii, 8; ix, 10, 11, see the article by G. E. Post in Hastings’ Dictionary of the Bible, vol. i, p. 63, and W. H. Schoff, The Ship “Tyre” 1920, pp. 27, 28.

Turning to its sacred uses, we find that idols are carved from the wood. It is interesting to notice that among the treasures brought from India by Hiuen Tsiang were two sandalwood figures of Buddha, the larger of which was modelled on one made by the desire of Udāyana, King of Kauśāmbī (see Beal, Life of Hiuen Tsiang, pp. 213, 214). An emulsion of the wood is given as an offering to the gods, and an incense made of it is burned before them. A considerable export for making incense followed in the wake of Buddhism, and the amount used in this fashion by China was, and still is, particularly large. The Parsis consume large quantities, usually of an inferior variety, in their fire-temples. The relatives of the deceased who can afford to buy the wood, do so for cremation purposes, while all Hindus add at least one piece of it to the funeral pyre.

Although sandalwood was used in India from at least the fifth century B.C., it was almost entirely confined to Buddhist and Hindu peoples. In the West it appears not to have been known until the beginning of the Christian era, the earliest Roman reference being in the famous Periplus of the Erythræan Sea (circa a.d. 80). Here we read (36) of two market-towns on the Persian Gulf called Apologus [Obollah of Saracen times], and Ommana [Oman]:

“To both of these market-towns large vessels are regularly sent from Barygaza, loaded with copper and sandalwood and timbers of teakwood and logs of blackwood and ebony” (see SchofFs edition, 1912, pp. 36, 152, and further, Lassen, Indische Alterthumskunde, vol. i, p. 287).

Barygaza is the modern Broach in the Gulf of Cambay, the Greek name being from the Prakrit Bharukaccha, a corruption of the Sanskrit Bhṛgukaccha.

The wood is mentioned by Cosmas Indicopleustes (sixth century a.d.) under the name Tzandāna, and frequently by the early Arab traders who visited India and China. Both Cosmas and the Arabs attributed the wood to China, the mistake arising from the fact that the Chinese vessels trading with the merchants of Bagdad had picked up cargoes of the wood at Ceylon and such Indian ports as Broach. (See M'Crindle’s edition, Hakluyt Soc., 1897, p. 366.) As was only to be expected with a people so fond of perfumes as the Mohammedans, sandalwood became a great favourite with them, and caused a considerable spread of its use in the Middle and Near East.

For early European references see Yule and Burnell, Hobson Jobson, under “Sandal.” (The article in the 1903 edition adds nothing to that of 1886.)

With regard to the modern sandalwood trade of both India and the various islands of the Malay Archipelago and the Pacific we are not concerned, but a good idea of this may be got from the following:—

Watt, op. cit.j vol. iv, pt. ii, pp. 466, 467; Seemann, op. cit., p. 78 et seq.; “C.B.,” Leisure Hour, 1869, pp. 598-600; and the anonymous articles in The Practical Magazine, vol. vii, 1877, pp. 373, 374, and in Scientific American, vol. cviii, 1913, p. 558, which deals largely with the need for great and more careful cultivation of the tree, and finally in the Annual Statement of the Seaborne Trade of British India, the most recent copies of which show that the export trade has steadily increased since 1921, and now stands at about eight hundred tons per annum.

So far, we have spoken only of the Santalum album, which is the one referred to in the Ocean. Mention, however, should also be made of the Red Sanders Tree, Pterocarpus santalinus, which is used chiefly as a dye. Owing, however, to the modern introduction of aniline dyes, its use in this capacity has been very considerably curtailed. See further, Watt, op. cit., vol. vi, pt. i, p. 359 et seq.; and D. Hooper, “Caliature Wood,” Nature, vol. lxxxvi, 1911, pp. 311, 312.—n.m.p.