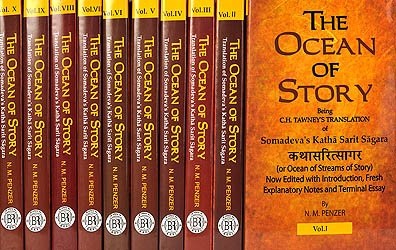

Kathasaritsagara (the Ocean of Story)

by Somadeva | 1924 | 1,023,469 words | ISBN-13: 9789350501351

This is the English translation of the Kathasaritsagara written by Somadeva around 1070. The principle story line revolves around prince Naravāhanadatta and his quest to become the emperor of the Vidhyādharas (‘celestial beings’). The work is one of the adoptations of the now lost Bṛhatkathā, a great Indian epic tale said to have been composed by ...

Note on “women whose love is scorned”

Note: this text is extracted from Book VIII, chapter 49.

The “women whose love is scorned” motif has already been discussed in Vol. II, pp. 120-124. The story of Guṇaśarman and Queen Aśokavatī, in our present text (p. 87 et seq.), is a very good example of the motif, and closely resembles in its main outline that of Joseph and Potiphar’s wife. It is interesting to note that in the Biblical (Authorised Version) story it is Joseph’s skill in the interpretation of dreams that ultimately gets him out of prison and advances him so high in Pharaoh’s estimation. So, too, it is Guṇaśarman’s skill that makes him so valuable and trusted a minister to Mahāsena.

There is, however, one great difference in the two tales. In the Indian story (and in practically every variant) the husband figures throughout, and finally discovers the truth. In the Biblical story the sudden interest of Pharaoh occurs quite by chance, and, without any questioning as to the cause of his imprisonment, Joseph is set over all the land of Egypt. We hear no more of Potiphar or his wife.

Now, in the Koranic version, Potiphar is soon convinced that his wife’s charge is false, because Joseph’s garment is torn at the back. Accordingly he says:

“O Joseph, take no further notice of this affair: and thou, O woman, ask pardon for thy crime, for thou art a guilty person.”

The scandal soon becomes the one topic of conversation among the women of the town, and to quiet them Potiphar’s wife asks a number of them to a banquet, giving them each a knife. She then calls in Joseph, and, overcome by his beauty, they all cut their hands, exclaiming:

“O God! this is not a mortal; he is no other than an angel deserving the highest respect.”

Thus her weakness for him is duly appreciated.

In spite, however, of Joseph’s proved innocence, it is thought better for him to be put in prison—and thus the incident of dreams can be introduced.

It was this Koranic version which Firdausi used for his Yūsuf u Zulaikhā, a poem of 9000 couplets.

Since the issue of Vol. II Professor Bloomfield has forwarded me a most valuable paper by himself on “Joseph and Potiphar in Hindu Fiction,” which appeared in the Trans. Amer. Phil. Assoc., vol. liv, 1923, pp. 141-167. Among others he speaks of the Kashmir version of the story now translated in Stein and Grierson’s Hatims Tales, pp. 33-37, with notes on pp. xxxiv and xxxv by Crooke.

The chief point to notice in this version is the introduction of the motif of selecting a king by animal divination. I shall have more to say on this motif in Vol. V (Chaper LXV), where an elephant selects the merchant’s son as king.

The references given on p. 145 to the Mahābhārata have suffered from misprints. The incident of Satyavatī and Bhīṣma occurs in I, ciii, 1 et seq., and not I, liv, while that of Uttaṅka is to be found in I, iii.

On p. 161 the variant of the Joseph motif in the Kathā Sarit Sāgara should read xxxiii, 40 et seq.

After giving extracts from several references mentioned in my note in Vol. II (pp. 120-124-), Professor Bloomfield draws attention to the fact that the Jaina texts handle the “scorned love of women” motif more familiarly than any other branch of Hindu literature, in connection with their ethics, which are systematised to a degree not quite reached by any other Hindu religious sect. Among the five lighter vows (aṇuvrata) to be observed as far as possible by the laity are discernment (viveka) and unbroken chastity (abrahmavirati); both forbid adultery, and consequently the Jaina texts contain stories showing the downfall of the wrongdoer and the ultimate triumph of chastity.

Of the extracts quoted the most interesting story and the one in which the motif is developed to its highest point is undoubtedly that in Vijayadharmasūri’s Mallinātha Caritra, vii, 198 et seq. As the circulation of the Trans. Amer. Phil. Assoc, unfortunately appears to be small in England, I will quote Professor Bloomfield’s account of the story in full:

In Campā rules King Dadhivāhana with his queen, Abhayā, who is attended by a sly duenna, named Paṇḍitā. In the same city lives a rich merchant, Vriṣabhadāsa (or Riṣabhadāsa), whose wife Arhaddāsī bears him a son who is called Sudarśana, “Handsome.” After growing into manhood, endowed with every bodily and spiritual perfection, he is married to a lovely maiden of good family, Manoramā. After his father takes the Jaina vow (dikṣā), he is left in possession of all his belongings, and lives as a Śrāddha of high quality, honoured alike by the king and his fellow-citizens.

Now Sudarśana has an intimate friend, Kapila, chaplain (jmrodhā) of the king. His beautiful wife, Kapilā, clever, and endowed with the sixty-four accomplishments of a well-born lady, is rendered wayward by youth’s love-fervour.

One day Kapila praises his friend Sudarśana as

“a galaxy of virtues, delightful even to the gods.” From that moment Kapilā knows no peace in her desire to see Sudarśana. Her husband happens to go to another town on the business of the king; she scents opportunity, and instructs a duenna of hers to go to Sudarśana, and say to him that his friend, her husband, is sick; why does he not come to make inquiry about him? Sudarśana tenderly hastens over and says: “Wife of my brother, where is my brother?”

She tells him that he is asleep in his chamber, let him quickly go there. Finding that his friend is not there, he reproves her:

“Wife of my brother, why do you fool me like a child?”

She bares her heart, navel, breasts, and from her eyes dart the missiles of Kāma upon him.

She says:

“From the moment that I heard an account of your beauty and all your other excellences, I have burned with the love of you. Quench my body with the ambrosia of your beauty, else it shall become a heap of ashes in the fire of Kandarpa.”

Craftily Sudarśana holds her off by claiming that he is a eunuch, though he goes about in the garb of a man. He makes his escape, reflecting that it is not safe to go to another’s house whose inmates may be full of guile.

Comes spring, when King Love awakes from his slumbers, when groves are alive with bees and birds, and on the branches of every tree hangs a pleasure-swing. To disport themselves in such a grove come King Dadhivāhana and his retinue; Sudarśana in all his beauty; the Brāhman Kapila with his wife Kapilā; Queen Abhayā; and also Manoramā, Sudarśana’s wife, with her four children. When Kapilā sees Manoramā playing about, she asks her friend, Queen Abhayā, who she may be, and learns that Manoramā and her children are Sudarśana’s family. Kapilā exclaims:

“Gracious me, how clever are the wives of merchants! Her husband is a eunuch; however came the children? As easily would a lotus grow in the sky, or the wind be tied up in the knot of a garment” [the ordinary Hindu pocket].

When the queen asks her to explain, she relates her escapade with Sudarśana.

The queen laughs at her, and teases her by saying that though she thinks herself wise, she does not understand the true meaning of the science of love (kāmaśāstrārtha).

“This merchant is ever a eunuch towards the beautiful loves of other men, as though they be sisters, but not towards his own wife. You have been tricked by the guile of this cunning man, you foolish woman.”

Kapilā acknowledges the scorn, and at the same time points out ironically, we may guess, that the queen is brilliant with skill in the kāmaśāstra.

She therefore challenges her to try her hand:

“I shall know for certain your cleverness in matters of love, if, O Queen, you shall make Sudarśana sport with you, without shame, just as if he were the king.”

Queen Abhayā accepts the dare, returns to the palace, and holds counsel with her old confidential nurse Paṇḍitā. She bids her play some deceptive trick (kāitavanātaka) which would bring her together with Sudarśana. The duenna remonstrates: it is not proper that she, the beloved of the king, should do a thing which works mischief both in this and the next world. Moreover, Sudarśana is a pious householder, who regards others’ wives as sisters (paranāñsahodara). How is he to be brought to the palace like a noble elephant from the forest? Yea, if he should come, he would not do as the queen desires. The queen insists that she has bet with Kapilā, and the nurse finally proposes the following device:—Sudarśana is in the habit of fasting on each day of the four changes of the moon, standing silently in some public place in the abstracted kāyotsarga posture. She will then wrap him in the folds of her garment; lead him roundabout two or three times; and introduce him into the palace by pretending to the door-guards that he is an image of Kandarpa, the God of Love. All this happens as planned. When Queen Abhayā sees him, she begins to agitate him with the unfeathered yet sharp darts from her side-wise coquettish eyes.

She asks him to take pity, and bestow upon her the ambrosial paradise pleasure of his embraces:

“To what purpose do you, foolish man, practise the rigours of asceticism, now that you have me, who would be hard to reach even by ascetic vows.”

And afterwards:

“Why do you spurn me, an unprotected female, that is being slain by the arrows of the God of Love? Surely you can take pity on a woman. Thinking of you, my days became long as a hundred Kalpas; my nights long as days of Brahmā. In my far-roving dreams I have you before my eyes in a thousand shapes, single-shaped though you be.”

But dharma-devoted Sudarśana firmly spurns her. Abhayā keeps on all night, luring him with her body’s charms and with artful songs. Dawn, gathering up the darkness with her hands (rays), rises, as if for the express purpose of looking at Sudarśana, pure in devotion to his wife.

Sudarśana’s obduracy drives Abhayā to threats:

“This vow of yours shall not block fate! I shall now tear my body with crores of nail scratches, and make a wild outcry [ phutkarishyetarām].”

When yet he is not shaken, she rouses the palace with her shrieks—for devoted as well as disaffected women both kill:

“Hear, ye guards. This fellow, forcibly bent upon showing me love, is tearing me with his sharp nails. Run quickly, run!”

The king comes to the spot, asks Sudarśana what he has to say, but he stands silent. The king orders him to be impaled upon a stake. To the ear-piercing cry of “Runner after other men’s wives!” the executioners set him on the back of an ass, a nimba-leaf turban upon his head, his body smeared with soot. Bitterly they mock him as they exhibit him through the great city, on the way to the “grove of the Fathers”— i.e. the cemetery which is the place of execution. But Sudarśana keeps thinking on the fivefold obeisance to the Jaina Saviours (Arhats), the pañcanamaskṛti.

Now Manoramā, Sudarśana’s noble wife, hears his evil story. She does not believe that her wise, law-abiding and chaste husband can have made advances to the king’s chief wife, but, on the contrary, suspects her of a trick, because, empty of soul, though lovely outside, she is a very treasury of guile. What will not an impure woman do when thwarted in her desires? A woman loosed from the scabbard of her modesty becomes a fear-inspiring sword. Manoramā then bathes, puts on white robes, and without delay worships an image of the Arhat.

Before the Arhat’s executive female divinity she makes by proxy a truth-declaration in behalf of her husband:

“If this Sudarśana is indifferent to the wives of others, then let me be united with him at once!”

By the force of Manoramā’s spiritual power the Arhat’s ancillary divinity arrives at the place of execution, where Sudarśana sits impaled upon the stake. She turns the stake into a throne. When the executioners hold their sharp swords to Sudarśana’s throat, these turn into garlands, lovely with bees buzzing about them. The rope around his neck becomes a jewelled necklace. She produces by her magic a rock which she holds over the city, like a lid about to shut down on it. The divinity threatens to let down the rock upon sinful king, retinue and citizens alike. She chides the king for not having understood the character of his wife, and compels him to expiate his sin by placing Sudarśana upon a noble elephant, and holding, like an umbrella-bearer, the royal umbrella over his head. Thus Sudarśana, to the exultant shouts of the citizens, lauded by bards, to the beat of festal drums, returns to his home. The king then takes holy vows, but Abhayā hangs herself, and is reborn as a Vyantara demon. The pander-nurse, Paṇḍitā, flees to Pāṭaliputra, where she lives in the house of the courtesan Devadattā.

On p. 154 of his article on the “Potiphar” motif Bloomfield gives several other references to Jaina works.—n.m.p.