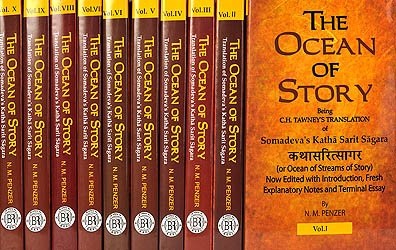

Kathasaritsagara (the Ocean of Story)

by Somadeva | 1924 | 1,023,469 words | ISBN-13: 9789350501351

This is the English translation of the Kathasaritsagara written by Somadeva around 1070. The principle story line revolves around prince Naravāhanadatta and his quest to become the emperor of the Vidhyādharas (‘celestial beings’). The work is one of the adoptations of the now lost Bṛhatkathā, a great Indian epic tale said to have been composed by ...

Note on Tantric rites in the Mālatī Mādhava

Note: this text is extracted from Book V, chapter 25:

Bhavabhūti, the great romantic dramatist of India, who flourished towards the end of the seventh century, has three plays attributed to him—the Mālafi Mādhava, the Mahā Vira Charita, and the Uttara Rāma Charita.

It is in the first of these that we have such insight into the esoteric rites of Hinduism. The Tantric practices pictured here are so vivid and detailed that imagination must have been aided by a knowledge of actual fact. The goddess whose worship figures so largely in the play is Cāmuṇḍā, a form of Durgā. Among the rites of the high priest is the sacrifice of a human virgin, and by means of sorcery Mālatī is led to the dread temple of the goddess.

The hero Mādhava has decided, like Faust, to call the powers of evil to his aid in his winning of Mālatī. Accordingly he prepares for the necessary Tantric rites by procuring human flesh as an offering—flesh which had been obtained not by the common method of cutting it from a man slain in battle, but, w’e are led to suppose, by more grim and sanguinary means. Chance takes Mādhava, with his offering of flesh, to the very temple where, little as he knows it, his beloved is bound and about to be offered up as a sacrifice to Cāmuṇḍā.

The temple is situated in a burning-ground and as Mādhava approaches the terrors of the place begin to have their effect on him. On hearing a noise behind he speaks as follows (the extracts given here are taken from Act V of the play, as translated by H. H. Wilson; see his Theatre of the Hindus, vol. ii, 1827):—

“Now wake the terrors of the place, beset

With crowding and malignant fiends; the flames

From funeral pyres scarce lend their sullen light,

Clogged with their fleshly prey, to dissipate

The fearful gloom that hems them round. Pale ghosts

Sport with foul goblins, and their dissonant mirth

In shrill respondent shrieks is echoed round.

Well, be it so. I seek, and must address them.

Demons of ill, and disembodied spirits,

Who haunt this spot, I bring you flesh for sale.

The flesh of man untouched by trenchant steel,

And w’orthy your acceptance. (A great noise.)

How, the noise

High, shrill, and indistinct, of chattering sprites

Communicative fills the charnel ground.

Strange forms like foxes flit along the sky;

From the red hair of their lank bodies darts

The meteor blaze; or from their mouths that stretch

From ear to ear thickset with numerous fangs,

Or eyes or beards or brows, the radiance streams.

And now I see the goblin host: each stalks,

On legs like palm-trees, a gaunt skeleton,

Whose fleshless bones are bound by starting sinews,

And scantly cased in black and shrivelled skin:

Like tall and withered trees by lightning scathed

They move, and as amidst their sapless trunks

The mighty serpent curls—so in each mouth

Wide-yawning rolls the vast blood-dripping tongue.

They mark my coming, and the half-chewed morsel

Falls to the howling wolf—and now they fly.

(Pauses and looks round.)

Race—dastardly as hideous—all is plunged

In utter gloom. (Considering.) The river flows before me,

The boundary of the funeral ground, that winds

Through mouldering bones its interrupted way.

Wild raves the torrent as it rushes past,

And rends its crumbling bank; the wailing Owl

Hoots through its skirting groves, and to the sounds

The loud-moaning Jackal yells reply.”

Suddenly Mādhava hears a voice and rushes off alarmed.

Meanwhile the priest and priestess in the temple have dressed the luckless Mālatī as a victim and a ritual dance is being performed round her as she lies bound and terrified. The priest begins his incantations thus:

“Hail—hail—Cāmuṇḍā, mighty goddess, hail!

I glorify thy sport, when in the dance,

That fills the court of Śiva with delight,

Thy foot descending spurns the earthly Globe.

Beneath the weight the broad-backed tortoise reels;

The egg of Brahmā trembles at the shock;

And in a yawning chasm, that gapes like hell,

The sevenfold main tumultuously rushes.The elephant hide that robes thee, to thy steps

Swings to and fro—the whirling talons rend

The crescent on thy brow—from the torn orb

The trickling nectar falls, and every skull

That gems thy necklace laughs with horrid life—

Attendant spirits tremble and applaud.

The mountain falls before thy powerful arms,

Around whose length the sable serpents twine

Their swelling forms, and knit terrific bands,

Whilst from the hood expanded frequent flash

Envenomed flames—As rolls thy awful head,

The lowering eye that glows amidst thy brow

A fiery circle designates, that wraps

The spheres within its terrible circumference:

Whilst by the banner on thy dreadful staff,

High waved, the stars are scattered from their orbits.

The three-eyed God exults in the embrace

Of his fair Spouse, as Gaurī sinks appalled

By the distracting cries of countless fiends,

Who shout thy praise. Oh, may such dance afford

Whate’er we need—whate’er may yield us happiness.”

While this is proceeding Mādhava enters unseen and slaying the priest releases Mālatī.

There are many other striking episodes in the play, but the above is sufficient to show the Tantric basis of the scene described in pp. 198, 199 and 205 of this volume.— n.m.p.