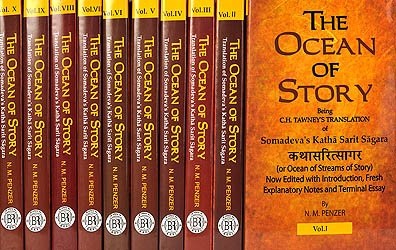

Kathasaritsagara (the Ocean of Story)

by Somadeva | 1924 | 1,023,469 words | ISBN-13: 9789350501351

This is the English translation of the Kathasaritsagara written by Somadeva around 1070. The principle story line revolves around prince Naravāhanadatta and his quest to become the emperor of the Vidhyādharas (‘celestial beings’). The work is one of the adoptations of the now lost Bṛhatkathā, a great Indian epic tale said to have been composed by ...

Note on precautions observed in the birth-chamber in ancient India

Note: this text is extracted from Book IV, chapter 23.

On page l6l we saw that the room in which Vāsavadattā was confined had its windows covered with sacred plants. These were to act as a protection against the possible intrusions of evil spirits, whose malign influence was feared on such an auspicious occasion. Furthermore, the room was hung with various weapons. Here again we have a charm to ward off danger.

In India iron does not bring good luck, but scares away evil spirits, consequently weapons hung up in the birth-chamber act as a powerful protection. In the same way our horseshoe is really only lucky because of the power in iron to repel evil influences. Steel is equally effective. In her Rites of the Twice-born, Mrs Stevenson, in describing the Brāhman birth-chamber, states that the scissors which have been used to sever the umbilical cord are put under the pillow on which the young mother’s head is resting, and the iron rod with which the floor has been dug up for the burial of the after-birth is placed on the ground at the foot of the bed. This iron rod is part of a plough, and, if the householder does not possess one of his own, it is specially borrowed for the occasion; its presence is so important that it is not returned for six days, however much its owner may be needing it. The midwife, before leaving, often secretly introduces a needle into the mattress of the bed, in the hope of saving the mother after-pains.

Frazer (Golden Bough, vol. iii, p. 234 et seq.) has collected numerous examples showing the dislike of spirits for iron in various parts of the world, especially Scotland, India and Africa. Among the Majhwār, an aboriginal tribe in the hill country of South Mirzapur, an iron implement such as a sickle or a betel-cutter is constantly kept near an infant’s head during its first year for the purpose of warding off the attacks of ghosts (W. Crooke, Tribes and Castes of the North-Western Provinces and Oudh, vol. iii, p. 431). Among the Maravars, an aboriginal race of Southern India, a knife or other iron object lies beside a woman after childbirth to keep off the devil (F. Jagor, “Berichtüber verschiedene Volksstämme in Vorderindien,” Zeitschrift fur Ethnologie, vol. xxvi, 1894, p. 70). When a Māla woman is in labour, a sickle and some nīm leaves are always kept on the cot. In Malabar people who have to pass by burning-grounds or other haunted places commonly carry with them iron in some form, such as a knife, or an iron rod used as a walking-stick. When pregnant women go on a journey, they carry with them a few twigs or leaves of the nīm tree, or iron in some shape, to scare evil spirits lurking in groves or burial-grounds which they may pass (E. Thurston, Ethnographic Notes in Southern India, Madras, 1906, p. 341; and CastesaridTribes of Southern India, vol. iv, p. 369 et seq.). See also the articles on pregnancy observances in the Pañjāb by H. A. Rose, Joum.Anth. Inst., vol. xxxv, 1905, pp. 271-282.

In Annam parents sometimes sell their child to a smith, who puts an iron anklet on the child’s foot, usually adding a small iron chain. After the child has grown and all danger from the attack of evil spirits is over, the anklet is broken.

The use of the sword to scare away evil spirits during childbirth is found in the Philippines, where the husband strips naked (see p. 117 of this volume) and, standing on guard either inside the house or on the roof, flourishes his sword incessantly until the child is born.

In Malaya a piece of iron is numbered among the articles necessary for the defence of infancy against its natural and spiritual foes. See R. J. Wilkinson, Papers on Malay Subjects, part i, p. 1, Kuala Lumpur, 1908.

As iron frightens demons away it is not surprising that it is used in cases of illness. Thus, during an outbreak of cholera, people often carry axes or sickles about with them. On the Slave Coast of Western Africa, when her child is ill, a mother will attach iron rings and bells to the child’s ankles and hang iron chains round its neck.

Iron has a similar significance of driving away spirits at death, thus the chief mourners will carry iron with them. When a woman dies in childbed in the island of Salsette, they put a nail or other piece of iron in the folds of her dress; this is done specially if the child survives her. The intention plainly is to prevent her spirit from coming back; for they believe that a dead mother haunts the house and seeks to carry away her child (G. F. D’Penha, “Superstitions and Customs in Salsette,” Indian Antiquary, vol. xxviii, 1899, p. 115).

In all these cases the original cause of the dread of iron by evil spirits appears to be simply that the spirits themselves date back to Stone Age times, and the discovery of iron, with its enormous advantages over stone, attached to it miraculous powers which the evil spirits, in their ignorance, came to dread.

Crooke in his article, “Charms and Amulets (Indian),” Hastings’ Ency. Rel. Eth. (vol. iii, p. 443), gives other useful references. He first refers to W. Johnson, Folk Memory, 1908, p. 169 et seq., where the protective value of iron is described. When a child is still-born, the Burmese place iron beside the corpse, with the invocation:

“Never more return into thy mother’s womb till this metal becomes as soft as down”

(Shway Yoe [Sir George Scott], The Burman, vol. i, p. 3).

The Vadvāls of Thāna, in order to guard against the spirit which attacks the child on the sixth day after birth (an unconscious recognition of the danger from infantile lockjaw, caused by neglect of sanitary precautions), place an iron knife or scythe on the mother’s cot, and an iron bickern at the door of the lying-in room—a custom which also prevails in the Pañjāb (Campbell, Notes on the Spirit Basis of Belief and Custom, Bombay, 1885, p. 387; Malik Muhammad Dīn, The Bahāwalpur State, Lahore, 1908, p. 98). An iron bracelet is worn by all Hindu married women, those of high rank enclosing it in gold (Rajendralala Mitra, The Indo-Aryans, London, 1881, vol. i, pp. 233, 279; Risley, Tribes and Castes of Bengal, vol. i, p. 532, 533; vol. ii, p. 41). In the form of the sword it has special power. When a birth occurs among the Kachins of Upper Burma, guns are fired, knives (dhā) and torches are brandished over the mother, and old rags and chillies are burned to scare demons by the stench (Gazetteer,Upper Burma, vol. i, pt. i, p. 399).

The Mohammedans of North India wave a knife over a sufferer from cramp, with the invocation:

“I salute God! The knife is of steel! The arrow is sharp! May the cramp cease through the power of Muhammad, the brave one!”

(North Indian Notes and Queries, vol. v, p. 35).

On the Irrawaddy river in Burma iron pyrites is valued as a charm against alligators (Yule, Mission to Ava, London, 1858, p. 198). A curious belief in the sanctity of iron appears among the Doms, a criminal tribe of North India. They inherit from the Stone Age the belief that it is unlawful to commit a burglary with an iron tool; anyone disobeying this rule is expelled from the community, and it is believed that the eyes of the offender will start from his head (North Indian Notes and Queries, vol. v, p. 63).

Apart from the reference to the birth-chamber of the son of the King of Vatsa being hung with various weapons, we are told that they were “rendered auspicious by being mixed with the gleam of jewel-lamps, shedding a blaze able to protect the child.” There are two similar descriptions in Chapters XXVIII and XXXIV, where the light of the lamps is eclipsed by the beauty of the expectant mother.

We have already seen (Vol. I, p. 77n1) that demons fear the light and can indulge in their machinations only when it is dark. The same idea obtains at the time of childbirth, for being a most critical period, evil spirits naturally try to take every advantage. Thus it is an almost universal custom to have lights in the birth-chamber to scare away such spirits as may be hovering round to do what harm they can.

“The rule that, where a mother and new-born child are lying, fire and light must never be allowed to go out,” says Hartland, “is equally binding in the Highlands of Scotland, in Korea, and in Basutoland; it was observed by the ancient Romans; and the sacred books of the Parsis enjoin it as a religious duty; for the evil powers hate and fear nothing so much as fire and light.”

Among the Chinese, as soon as the birth-pangs are felt, the women light candles and burn incense before the household shrine and gods. Red candles are also lighted in the chamber as at a wedding, the idea being that a display of joy and cheerful confidence repels all evil influences.

Crooke (op. cit. supra, pp. 444, 445) also gives useful references about the protecting powers of light and fire in all parts of the world.

The Nāyars of Malabar place lights, over which rice is sprinkled, in the room in which the marriage is consummated (Bull. Madras Museum, vol. iii, p. 234; cf. Dubois, Hindu Manners, Cuslotns and Ceremonies, p. 227). Among the Śavaras of Bengal the bridesmaids warm the tips of their fingers at a lamp, and rub the cheeks of the bridegroom (Risley, op. cit., vol. ii, p. 243). The Mohammedan Khojas of Gujarat place a four-wicked lamp near a young child, while the friends scatter rice (Bombay Gazetteer, vol. ix, pt. ii, p. 45). In Bombay the lamp is extinguished on the tenth day, and again filled with butter and sugar, as a mimetic charm to induce the light to come again and bring another baby (Pañjab Notes and Queries, vol. iv, p. 5). The Śrigaud Brāhmans of Gujarat at marriage wear conical hats made of leaves of the sacred tree Butea frondosa, and on the hat is placed a lighted lamp (Bombay Gazetteer, vol. ix, pt. i, p. 19 i and cf. idem, p. 272).

Fire is commonly used for the same purpose. The fires lit at the Holī spring festival are intended as a purgation of evil spirits, or as a mimetic charm to produce sunshine. Toucing fire is one of the methods by which mourners are freed from the ghost which clings to them. When an Arer woman of Kānara has an illegitimate child, the priest lights a lamp, plucks a hair from the woman’s head, throws it into the fire, and announces that mother and child are free from taboo (Bombay Gazetteer, vol. ix, pt. i, p. 215). The rite of fire-walking practised in many parts of the country appears to be intended as a means of purging evil spirits; and the fire lighted by all castes in the delivery-room seems to have the same object. Such use of fire is naturally common among the Zoroastrian fire-worshippers (Shea-Troyer, The Dabistān, Paris, 1843, vol. i, p. 317).

In the Nights (Burton, Supp., vol. i, p. 279) we read:

“When the woman came to her delivery, she gave birth to a girl-child in the night, and they sought fire of the neighbours.”

In the text of the Ocean of Story under discussion the lamps are described as

“jewel-lamps, shedding a blaze,” and in Chapter XXXIV we read of “a long row of flames of the jewel-lamps.”

Tawney gives a note to this latter reference, but does not tell us what jewel-lamps are. The question arises as to whether they are lamps encrusted with jewels, lamps carved out of a solid jewel, or jewels so bright that they do the service of lamps. The first seems quite probable, while the second is most unlikely and, as far as I can discover, does not appear in folk-tales. But the luminous jewel is of very common occurrence, and not only appears largely in Eastern fiction, but enters into Alexandrian myths and is found in the works of mediæval physiologists.

Clouston, Popular Tales and Fictions, vol. i, p. 412, gives references from the Gesta Romanorum, the Talmud, Pseudo-Callisthenes, Lucian’s De Dea Syria, The Forty Vazirs, and ends his note with “Jewel-lamps are often mentioned in the Kathā Sarit Sāgara,” so he evidently thought the references were to jewels.

In the Nights (Burton, vol. i, p. 166) a room is lit by a light which

“came from a precious stone big as an ostrich egg... and this jewel, blazing like the sun, cast its rays far and wide.”

On the other hand, lamps enter so enormously into Hindu ritual that one is inclined to think that lamps are really meant, especially when we read of the “long row of flames.” Whenever a luminous jewel is mentioned it is nearly always a single stone. There are exceptions, however. The gable of Prester John’s palace was lit at night by two carbuncles, one at either end. But a whole row of such jewels used for such a purpose is unheard of.— n.m.p.