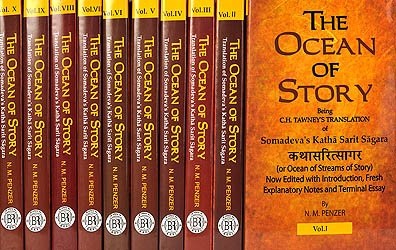

Kathasaritsagara (the Ocean of Story)

by Somadeva | 1924 | 1,023,469 words | ISBN-13: 9789350501351

This is the English translation of the Kathasaritsagara written by Somadeva around 1070. The principle story line revolves around prince Naravāhanadatta and his quest to become the emperor of the Vidhyādharas (‘celestial beings’). The work is one of the adoptations of the now lost Bṛhatkathā, a great Indian epic tale said to have been composed by ...

Chapter CXI

INVOCATION

MAY Gaṇeśa protect you, the ornamental streaks of vermilion on whose cheeks fly up in the dance, and look like the fiery might of obstacles swallowed and disgorged by him.

[M] (main story line continued) While Naravāhanadatta was thus living on that Ṛṣabha mountain with his wives and his ministers, and was enjoying the splendid fortune of emperor over the kings of the Vidyādharas, which he had obtained, once on a time spring came to increase his happiness. After long intermission the light of the moon was beautifully clear, and the earth, enfolded by the young fresh grass, showed its joy by sweating dewy drops, and the forest trees, closely embraced again and again by the winds of the Malaya mountain, were all trembling, bristling with thorns, and full of sap.[1] The warder of Kāma, the cuckoo, beholding the stalk of the mango-tree, with his note seemed to forbid the pride of coy damsels; and rows of bees fell with a loud hum from the flowery creepers, like showers of arrows shot from the bow of the great warrior Kāma.

And Naravāhanadatta’s ministers, Gomukha and the others, beholding at that time this activity of spring, said to Naravāhanadatta:

“See, King, this mountain of Ṛṣabha is altogether changed, and is now a mountain of flowers, since the dense lines of forest with which it is covered have their blossoms full-blown with spring. Behold, King, the creepers, which, with their flowers striking against one another, seem to be playing the castanets[2]; and with the humming of their bees to be singing, as they are swayed to and fro by the wind; while the pollen, that covers them, makes them appear to be crowned with garlands; and the garden made ready by spring, in which they are, is like the Court of Kāma. Look at this mango-shoot with its garland of bees; it looks like the bow of the God of Love with loosened string, as he reposes after conquering the world. So come, let us go and enjoy this festival of spring on the bank of the River Mandākinī, where the gardens are so splendid.”

When Naravāhanadatta had thus been exhorted by his ministers, he went with the ladies of his harem to the bank of the Mandākinī. And there he diverted himself in a garden resounding with the song of many birds, adorned with cardamom-trees,[3] clove-trees,[4] vakulas,[5] aśokas,[6] and mandāras.[7]

And he sat down on a broad slab of moonstone,[8] placing Queen Madanamañcukā at his left hand, accompanied by the rest of his harem, and attended by various princes of the Vidyādharas, of whom Caṇḍasiṃha and Amitagati were the chief; and while drinking wine and talking on various subjects, the sovereign, having observed the beauty of the season, said to his ministers:

“The southern breeze is gentle and soft to the feel; the horizon is clear; the gardens in every corner are full of flowers and fragrant; sweet are the strains of the cuckoo, and the joys of the banquet of wine; what pleasure is wanting in the spring? Still, separation from one’s beloved is during that season hard to bear. Even animals[9] find separation from their mates in the spring a severe affliction. For instance, behold this hen-cuckoo here distressed with separation! For she has been long searching for her beloved, who has disappeared from her gaze, with plaintive cries, and not being able to find him she is now cowering on a mango, mute and like one dead.”

When the king had said this, his minister, Gomukha, said to him:

“It is true, all creatures find separation hard to bear at this time; and now listen, King; I will tell you in illustration of this something that happened in Śrāvastī.

167. Story of the Devoted Couple, Śūrasena and Suṣeṇā[10]

In that town there dwelt a Rājput, who was in the service of the monarch, and lived on the proceeds of a village. His name was Śūrasena, and he had a wife named Suṣeṇā, who was a native of Mālava. She was in every respect well suited to him, and he loved her more than life.

One day the king summoned him, and he was about to set out for his camp, when his loving wife said to him:

“My husband, you ought not to go off and leave me alone; for I shall not be able to exist here for a moment without you.”

When Śūrasena’s wife said this to him, he replied:

“How can I help going, when the king summons me? Do you not understand my position, fair one? You see, I am a Rājput, and a servant, dependent on another for my subsistence.”

When his wife heard this she said to him, with tears in her eyes:

“If you must of necessity go, I shall manage to endure it somehow, if you return not one day later than the commencement of spring.”

Having heard this, he at last said to her:

“Agreed, my dear! I will return on the first day of the month Chaitra, even if I have to leave my duty.”

When he said this, his wife was at last induced to let him go; and so Śūrasena went to attend on the king in his camp. And his wife remained at home, counting the days in eager expectation, looking for the joyful day on which spring begins, on which her husband was to return. At last, in the course of time, that day of the spring festival arrived, resonant with the songs of cuckoos, that seemed like spells to summon the God of Love. The humming of bees, drunk with the fragrance of flowers, fell on the ear, like the twanging of Kāma’s bow as he strung it.

On that day Śūrasena’s wife Suṣeṇā said to herself:

“Here is that spring festival arrived; my beloved will, without fail, return to-day.”

So she bathed, and adorned herself, and worshipped the God of Love, and remained eagerly awaiting his arrival.

But the day came to an end and her husband did not return, and during the course of that night she was grievously afflicted by despondency, and said to herself:

“The hour of my death has come, but my husband has not returned; for those whose souls are exclusively devoted to the service of another do not care for their own families.”

While she was making these reflections, with her heart fixed upon her husband, her breath left her body, as if consumed by the forest-fire of love.

In the meanwhile Śūrasena, eager to behold his wife, and true to the appointed day, got himself, though with great difficulty, relieved from attendance on the king, and mounting a swift camel accomplished a long journey and, arriving in the last watch of the night, reached his own house. There he beheld that wife of his lying dead, with all her ornaments on her, looking like a creeper, with its flowers full blown, rooted up by the wind. When he saw her, he was beside himself, and he took her up in his arms, and the bereaved husband’s life immediately left his body in an outburst of lamentation.

But when their family goddess, Caṇḍī, the bestower of boons, saw that that couple had met their death in this way, she restored them to life out of compassion. And after breath had returned to them, having each had a proof of the other’s affection, they continued inseparable for the rest of their lives.

[M] (main story line continued)

“Thus, in the season of spring, the fire of separation, fanned by the wind from the Malaya mountain, is intolerable to all creatures.”

When Gomukha had told this tale, Naravāhanadatta, thinking over it, suddenly became despondent. The fact is, in magnanimous men, the spirits, by being elevated or depressed, indicate beforehand the approach of good or evil fortune.[11]

Then the day came to an end, and the sovereign performed his evening worship, and went to his bedroom, and got into bed, and reposed there. But in a dream at the end of the night {see notes on dreams} he saw his father being dragged away by a black female towards the southern quarter.

The moment he had seen this he woke up, and, suspecting that some calamity might have befallen his father, he thought upon the science named Prajñapti,[12] who thereupon presented herself, and he addressed this question to her:

“Tell me, how has my father the King of Vatsa been going on? For I am alarmed about him on account of a sight which I saw in an evil dream.”

When he said this to the science that had manifested herself in bodily form, she said to him:

“Hear what has happened to your father the King of Vatsa. When he was in Kauśāmbī, he suddenly heard from a messenger, who had come from Ujjayinī, that King Caṇḍamahāsena was dead, and the same person told him that his wife, the Queen Aṅgāravatī, had burned herself with his corpse. This so shocked him, that he fell senseless upon the ground: and when he recovered consciousness, he wept for a long time, with Queen Vāsavadattā and his courtiers, for his father-in-law and mother-in-law who had gone to heaven. But his ministers roused him by saying to him:

‘In this transient world what is there that hath permanence? Moreover, you ought not to weep for that king, who has you for a son-in-law, and Gopālaka for a son, and whose daughter’s son is Naravāhanadatta.’

When he had been thus admonished, and roused from his prostration, he gave the offering of water to his father-in-law and mother-in-law.

“Then that King of Vatsa said, with throat half-choked with tears, to his afflicted brother-in-law, Gopālaka, who remained at his side out of affection[13]:

‘Rise up, go to Ujjayinī, and take care of your father’s kingdom, for I have heard from a messenger that the people are expecting you.’

When Gopālaka heard this he said, weeping, to the King of Vatsa:

‘I cannot bear to leave you and my sister, to go to Ujjayinī. Moreover, I cannot bring myself to endure the sight of my native city, now that my father is not in it. So let Pālaka, my younger brother, be king there with my full consent.’

When Gopālaka had by these words shown his unwillingness to accept the kingdom, the King of Vatsa sent his commander-in-chief, Rumaṇvat, to the city of Ujjayinī, and had his younger brother-in-law, named Pālaka, crowned king of it, with his elder brother’s consent.

“And reflecting on the instability of all things he became disgusted with the objects of sense, and said to Yaugandharāyaṇa and his other ministers:

‘In this unreal cycle of mundane existence all objects are at the end insipid; and I have ruled my realm, I have enjoyed my pleasures, I have conquered my enemies; I have seen my son in the possession of paramount sway over the Vidyādharas; and now my allotted time has passed away, together with my connections; and old age has seized me by the hair to hand me over to death; and wrinkles have invaded my body, as the strong invade the kingdom of a weakling[14]; so I will go to Mount Kāliñjara, and, abandoning this perishable body, will there obtain the imperishable mansion of which they speak.’

When “When they had said this to the king, being like-minded with himself, he formed a deliberate resolution, and said to his elder brother-in-law, Gopālaka, who was present:

‘I look upon you and Naravāhanadatta as equally my sons; so take care of this Kauśāmbī: I give you my kingdom.’

When the King of Vatsa said this to Gopālaka, he replied:

‘My destination is the same as yours, I cannot bear to leave you.’

This he asserted in a persistent manner, being ardently attached to his sister; whereupon the King of Vatsa said to him, assuming[15] an anger that he did not feel:

‘To-day you have become disobedient, so as to affect a hypocritical conformity to my will; and no wonder, for who cares for the command of one who is falling from his place of power?’

When the king spoke thus roughly to him, Gopālaka wept, with face fixed on the ground, and, though he had determined to go to the forest, he turned back for a moment from his intention.

“Then the king mounted an elephant, and accompanied by his queens, Vāsavadattā and Padmāvatī, set out with his ministers. And when he left Kauśāmbī the citizens followed him, with their wives, children and aged sires, crying aloud and raining a tempest of tears.

The king comforted them by saying to them:

‘Gopālaka will take care of you.’

And so at last he induced them to return, and passed on to Mount Kāliñjara; and he reached it, and went up it, and worshipped Śiva, and holding in his hand his lyre, Ghoṣavatī, that he had loved all his life, and accompanied by his queens that were ever at his side, and Yaugandharāyaṇa and his other ministers, he hurled himself from the cliff. And even as they fell, a fiery chariot came and caught up the king and his companions, and they went in a blaze of glory to heaven.”

When Naravāhanadatta heard this from the science he exclaimed, “Alas! My father!” and fell senseless on the ground. And when he recovered consciousness he bewailed his father and mother and his father’s ministers, in company with his own ministers, who had lost their fathers.

But the chiefs of the Vidyādharas and Dhanavatī admonished him, saying:

“How is it, King, that you are beside yourself, though you know the nature of this versatile world, that perishes in a moment, and is like the show of a juggler? And how can you lament for your parents, that are not to be lamented for, as they have done all they had to do on earth: who have seen you their son sole emperor over all the Vidyādharas?”

When he had been thus admonished he offered water to his parents, and put another question to that science:

“Where is my Uncle Gopālaka now? What did he do?”

Then that science went on to say to that king:

“When the King of Vatsa had gone to the mountain from which he meant to throw himself, Gopālaka, having lamented for him and his sister, and considering all things unstable, remained outside the city, and summoning his brother, Pālaka, from Ujjayinī, made over to him that kingdom of Kauśāmbī also. And then, having seen his younger brother established in two kingdoms, he went to the hermitage of Kaśyapa in the ascetic grove on the Black Mountain,[16] bent on abandoning the world. And there your uncle Gopālaka now is, clothed in a dress of bark, in the midst of self-mortifying hermits.”

When Naravāhanadatta heard that, he went in a chariot to the Black Mountain, with his suite, eager to visit that uncle. There he alighted from the sky, surrounded by Vidyādhara princes, and beheld that hermitage of the hermit Kaśyapa. It seemed to gaze on him with many roaming, black, antelope-like, rolling eyes, and to welcome him with the songs of its birds. With the lines of smoke ascending into the sky, where pious men were offering the Agnihotra oblations, it seemed to point the way to heaven to the hermits. It was full of many mountain-like, huge elephants, and resorted to by troops of monkeys[17]; and so seemed like a strange sort of Pātāla, above ground, and free from darkness.

In the midst of that grove of ascetics he beheld his uncle, surrounded by hermits, with long matted locks, clothed in the bark of a tree, looking like an incarnation of patience. And Gopālaka, when he saw his sister’s son approach, rose up and embraced him, and pressed him to his bosom with tearful eyes. Then they, both of them, lamented their lost dear ones with renewed grief: whom will not the fire of grief torture, when fanned by the blast of a meeting with relations? When even the animals there were pained to see their grief, Kaśyapa and the other hermits came up and consoled those two. Then that day came to an end, and next morning the emperor entreated Gopālaka to come to dwell in his kingdom.

But Gopālaka said to him:

“What, my child; do you not suppose that I have all the happiness I desire by thus seeing you? If you love me, remain here in this hermitage, during this rainy season, which has arrived.”

When Naravāhanadatta had been thus entreated by his uncle, he remained in the hermitage of Kaśyapa on the Black Mountain, with his attendants, for the term mentioned.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

There is a play on words here. Sanskrit poets suppose that joy produces in human beings trembling, horripilation and perspiration.

[2]:

So Tawney translates śamyālālavatīr. Śamyātāla means literally a wooden clapper for beating time, but whether it consisted of pear-shaped bowls of hard wood, which is what we mean by castanets, is impossible to say. Two distinct forms exist in India to-day—the Jhang, made of metal, which mostly resembles the Moorish and Spanish castanets, but consist of only one pair, and the Khartāls, which are long, smooth stones in the shape of a cow’s tongue, rather similar to nigger-minstrels’ “bones.” A pair is held in each hand. See Atiya Begum Fyzee Rahamin, Music of India, p. 62. She informs me that there remain very few people who can play the Khartāl. Whether India was the original home of the castanet is not known for certain, but what evidence there is, appears to be in favour of the theory. It is generally agreed that the Moors introduced the instrument into Spain “from the East.” Such a dance-loving nation as the Spaniards not only received it enthusiastically, but discovered that the pomegranate wood was unrivalled in the manufacture of the instrument. The tones differ considerably and improve with age. When in Granada I made detailed inquiries about them, and discovered the most prized pairs are those made from the black wood, with hardly any of the lighter brown showing at all. My finest-sounding pair, a deep rich note, is almost entirely black; while a light brown set I have is shrill in comparison. The κρόταλα of the Greeks were a kind of castanet made of a split reed, and were used to accompany dances. They corresponded to the Roman crotala used in the Dionysiac and Bacchanalian rites. Literature on castanets seems very scarce, and the only article I can find entirely devoted to them is: Soy Yo, “Antiquity of the Castanet,” Once a Week, vol. viii, 1863, pp. 609-610. Castanets of various woods, metals and ivory are found throughout the East, and specimens from China, Burma, India, Siam, Japan and Arabia can be seen at the South Kensington Museum. —n.m.p.

[3]:

Sanskrit elā, which may apply either to the Greater cardamom, Amomum subulatum, a native of Nepal; or to the Lesser cardamom, Elettaria cardamomum, which is indigenous in West and South India, as well as in Burma. Elā is mentioned by Suśruta in the first century a.d. or b.c. as forming part of a medicated “drum” used for snake-bites. It is also given as one of the three aromatic drugs (Tri-sugandhi); the other two being patra (or tejpatra, Cassia lignea) and tvak (or gudatvak, cinnamon). See Bhiṣagratna’s translation, vol. ii, p. 739, and vol. iii, p. 313. For full details of the two varieties of cardamom see Watt, Diet. Econ. Prod. Ind., vol. i, pp. 222-223, and (especially) vol. iii, pp. 227-2 36. For its use in betel-chewing see e.g. pp. 242, 247 of this volume.—n.m.p.

[4]:

Caryophyllus aromaticus (or Eugenia caryophyllata) is a native of the Moluccas, the flower-buds of which yield the cloves of commerce. In spite of attempts by the Dutch to restrict the cultivation to the island of Amboyna the clove-tree was introduced into Mauritius by the French in 1770 (who used the word clou, from which our “cloves” is derived, through its resemblance to a nail). Cloves were subsequently cultivated in Guiana, Brazil, the West Indies, Zanzibar, Java, Sumatra and India.

The history of the clove trade and the struggles between the Portuguese, Dutch, French and English forms a most exciting, though very bloody, story of early sea adventure to the “spice islands.” See Watt, op. cit., vol. ii, p. 202 et seq.; H. N. Ridley, Spices, pp. 155-196. Interesting accounts appear in several of the Hakluyt Society volumes: see e.g. G. P. Badger, Travels of Ludovico di Varthema, p. 245 et seq.; M. L. Dames, Book of Duarte Barbosa, vol. ii, p. 199; Yule and Cordier, Cathay and the Way Thither, vol. iv, p. 101 et seq. For the use of cloves in betel-chewing see e.g. pp. 241, 246, 247, 255 of the present volume. —n.m.p.

[5]:

I.e. Mimusops elengi, largely cultivated in India, but found wild in the Deccan and Malay Peninsula. The tree is chiefly cultivated for its ornamental appearance and its fragrant flowers. The latter are used for making garlands, stuffing pillows, etc., while the attar distilled from them is esteemed as a perfume. See further Watt, op. cit., vol. v, p. 249 et seq. —n.m.p.

[6]:

See p.7n4 of this volume.—n.m.p.

[7]:

Calotropis gigantea, the giant swallow-wort, known in Vedic times as arka (“wedge”) and in modern days as madār. It is used for numerous purposes—gutta-percha, dye, tan, paper-making, etc.—besides being largely employed for sacred, domestic, medicinal and agricultural purposes. For full details and references see Watt, op. cit., vol. ii, pp. 34-49.—n.m.p.

[8]:

This particular variety of feldspar comes almost entirely from the Dumbara district of the Central Province of Ceylon. It has been fully described in various papers by A. K. Coomaraswamy, as enumerated in La Touche, Bibliography of Indian Geology, pt. i, 1917, p. 102 et seq. —n.m.p.

[9]:

For anyonyasya the three India Office MSS. and the Sanskrit College MS. read anyasyāstām, which means: “Not to speak of other beings, even animals, etc.”

[10]:

This is only another form of the story on pp. 9-10 of Vol. II.

[11]:

Cf. Hamlet, Act V, sc. 2, 1. 223; Julius Cæsar, Act V, sc. 1,1. 71 et seq.

[12]:

See Vol. II, p.212n1 .—n.m.p.

[13]:

I read pārśvasthitaṃ for pārśvasthaṃ. The former is found in the three India Office MSS. and in the Sanskrit College MS.

[14]:

The word which means “wrinkles” also means “strong.” the ministers had been thus addressed by the king, they thought over the matter; and then they all, and Queen Vāsavadattā, said to him, with calm equanimity: ‘Let it be, King, as it has pleased your Highness; by your favour we also will try to obtain a high position in the next world.’

[15]:

The three India Office MSS. read kṛtvaiva for kṛtreva.

[16]:

Asitagiri.

[17]:

This passage is full of lurking puns. It may mean “full of world-upholding kings of the snakes, and of many Kapilas.”