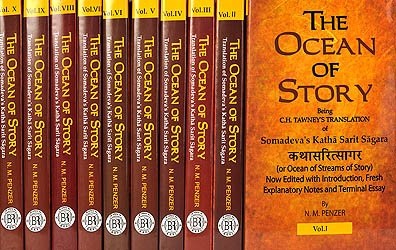

Kathasaritsagara (the Ocean of Story)

by Somadeva | 1924 | 1,023,469 words | ISBN-13: 9789350501351

This is the English translation of the Kathasaritsagara written by Somadeva around 1070. The principle story line revolves around prince Naravāhanadatta and his quest to become the emperor of the Vidhyādharas (‘celestial beings’). The work is one of the adoptations of the now lost Bṛhatkathā, a great Indian epic tale said to have been composed by ...

Chapter CX

[M] (main story line continued) THEN, the next day, the Emperor Naravāhanadatta, with his army, left that plateau of Kailāsa, and by the advice of King Kāñcanadaṃṣṭra, who showed him the way, went to that city of Mandaradeva named Vimala. And he reached that city, which was adorned with lofty ramparts of gold, and looked like Mount Sumeru come to adore Kailāsa, and, entering it, found that it resembled the sea in all but the presence of water, being very deep, characterised by unfailing prosperity,[1] and an inexhaustible mine of jewels.

And as the emperor was sitting in the hall of audience in that city, surrounded by Vidyādhara kings, an old woman of the royal harem came and said to him:

“Since Mandaradeva has gone to the forest, having been conquered by you, his wives desire to enter the fire; your Highness has now been informed and will decide upon the proper course.”

When this had been announced, the emperor sent those kings to them, and dissuaded them from suicide, and bestowed upon them dwelling-houses and other gifts, treating them like sisters. By that step he caused the whole race of the Vidyādhara chiefs to be bound to him with bonds of affection.

And then the grateful monarch anointed Amitagati, who had been designated before by Śiva, king over the realm of Mandaradeva, since he was loyal and could be trusted not to fall away, and he placed under him the princes who had followed Mandaradeva—namely, Kāñcanadaṃṣṭra and his fellows. And he diverted himself there in splendid gardens for seven days, being caressed by the fortune of the northern side of Kailāsa, as by a newly married bride.

And then, though he had acquired the imperial authority over the Vidyādhara kings of both divisions, he began to long for more. He set out, though his ministers tried to dissuade him, to conquer the inaccessible fields of Meru situated in the northern region, the home of the gods. For high-spirited men, though abundantly loaded with possessions, cannot rest without acquiring something still more glorious, advancing like blazing forest fires.

Then the hermit Nārada came and said to the king:

“Prince, what means this striving after things out of your reach, though you know policy? For one who out of overweening self-confidence attempts the impossible is disgraced like Rāvaṇa, who, in his pride, endeavoured to uproot Kailāsa. For even the sun and moon find Meru hard to overstep; moreover, Śiva has not bestowed on you the sway over the gods, but the sway over the Vidyādharas, so what need have you of Meru, the home of the gods? Dismiss from your mind this chimerical scheme. Moreover, if you desire good fortune, you must go and visit the father of Mandaradeva, Akampana by name, in the forest, where he is residing.”

When the hermit Nārada had said this, the emperor consented to do as he directed, and so he took leave of him, and returned whence he came.

And the politic emperor, having been advised by Nārada to relinquish his enterprise,[2] and remembering the destruction of Ṛṣabha, of which he had heard from Devamāya, and having reflected over the matter in his own mind, gave up the idea, and went to visit the kingly sage Akampana in the grove of ascetics. And when he reached that ascetic grove, it was crowded with great sages, engaged in contemplation, sitting in the posture called padmāsana, and so resembled the world of Brahmā.[3] There he saw that aged Akampana, wearing matted hair and a deerskin, looking like a great tree resorted to by hermits.

So he went and worshipped the feet of that ascetic, and that royal sage welcomed him and said to him:

“You have done well, King, in coming to this hermitage, for if you had passed on, neglectful of it, these hermits here would have cursed you.”

While the royal sage was saying this to the emperor, Mandaradeva, who was staying in that grove of ascetics, having taken the vows of a hermit, came to his father, accompanied by his sister, the Princess Mandaradevī. And Naravāhanadatta, when he saw him, embraced him, for it is fitting that truly brave men should show kindness to foes when conquered and pacified.

Then the royal sage Akampana, seeing Mandaradevī come with her brother, said to that emperor: “Here, King, is my daughter, Mandaradevī by name; and a heavenly voice said that she should be the consort of an emperor; so marry her, Emperor, for I give her to you.”

When the royal sage said this, his daughter said:

“I have four companions here, of like age, noble maidens; one is a maiden called Kanakavatī, the daughter of Kāñcanadaṃṣṭra; the second is the daughter of Kālajihva, Kālavatī by name; the third is the offspring of Dīrghadaṃṣṭra, named Śrutā; the fourth is the daughter of the King of Pauṇḍra, named Ambaraprabhā, and I am the fifth of those Vidyādhara maidens. We five, when roaming about, saw previously in a grove of ascetics this my destined husband, and, setting our hearts on him, we made an agreement together that we would all, at one and the same time, take him for our husband, but that, if any single one married him alone, the others should enter the fire, and lay the guilt at her door. So it is not fitting that I should marry without those friends of mine; for how could persons like myself commit the outrageous crime of breaking plighted faith?”[4]

When that self-possessed lady had said this, her father, Akampana, summoned those four Vidyādhara chiefs, who were the fathers of the four maidens, and told them exactly what had occurred; and they immediately thought themselves very fortunate, and brought those maidens, their daughters. Then Naravāhanadatta married the five in order, beginning with Mandaradevī. And he remained there with them many days, worshipping the hermits three times a day, at dawn, noon and sunset, while his attendants held high festival.

And Akampana said to him:

“King, you must now go to the Ṛṣabha mountain for the great ceremony of your coronation.”

And thereupon Devamāya also said to him:

“King, you must indeed do so, for the emperors of old time, Ṛṣabhaka and others, were anointed[5] on that mountain.”

When Hariśikha heard that, he spoke in favour of Naravāhanadatta’s being anointed emperor on the splendid mountain of Mandara, which was near; but a voice came from heaven:

“King, all former emperors went through the ceremony of their coronation on the Ṛṣabha mountain; do you also go there, for it is a holy place.”[6]

When the heavenly voice said this, Naravāhanadatta bowed before the hermits and Akampana, and set out thence for that mountain on an auspicious day. And he reached that northern opening of the cave of Triśīrṣa, with many great chiefs of the Vidyādharas, headed by Amitagati. There the emperor worshipped that Kālarātri, and entered the cave by that opening, and came out by the southern opening. And after he had come out with his forces he rested, at Devamāya’s request, in his palace for that day, together with his attendants.

And while he was there, he reflected that Śiva was near him on that mountain of Kailāsa, and he went of his own accord, with Gomukha, to visit the god. And when he reached his hermitage, he saw and adored the cow Surabhi and the sacred bull, and approached Nandin, the doorkeeper. And Nandin was pleased when the king circumambulated him, and opened the door to him, and then he entered and beheld Śiva, accompanied by Devī. The god diffused gladness afar by the streams of rays from the moon on his crest, that seemed to dart hither and thither as if conquered by the splendour of Gaurī’s face. He was playing with his beloved with dice, that, like eyes, were allowed at will to pursue their objects independently—that, though under his command, were ever restlessly rolling. And when Naravāhanadatta saw that giver of boons, and that goddess, the daughter of the mountain, he fell at their feet, and circumambulated them three times.

The god said to him:

“It is well, my son, that thou hast come hither; for otherwise thou mightest have suffered loss. But now all thy magic powers shall ever be unfailing. So go thou to the Ṛṣabha mountain, that holy place, and obtain there at once in fitting time thy great auguration.”

When the emperor had received this command from the god, he hastened to obey it, exclaiming: “I will do thy will,” and bowed before him and his wife, and returned to that palace of Devamāya.

The Queen Madanamañcukā playfully said to him on his return:

“Where have you been, my husband? You appear to be pleased. Have you managed to pick up here another set of five maidens?”

When she made use of these playful taunts, the prince gladdened her by telling her the real state of affairs, and remained with her in happiness.

And the next day, Naravāhanadatta, accompanied by a host of Gandharvas and Vidyādharas, making, as it were, a second sun in the heavens by his glorious presence, ascended his splendid car, with his wives and his ministers, and made for the Ṛṣabha mountain. And when he reached that heavenly hill, the trees, like hermits, with their creepers like matted hair waving in the wind, shed their flowers before him by way of a respectful offering. And there various kings of the Vidyādharas brought the preparations for the coronation on a scale suited to the might of their master. And the Vidyādharas came to his coronation from all quarters, with presents in their hands, all loyal, terrified, vanquished or respectful.

Then the Vidyādharas said to him:

“Tell us, King, who is to occupy half your throne, and to be anointed as queen consort?”

The king answered:

“The Queen Madanamañcukā is to be anointed together with me”;

and this at once set the Vidyādharas thinking.

Then a bodiless voice came from the air:

“Hearken, Vidyādharas! This Madanamañcukā is not a mortal; for she is Rati become incarnate, in order to be the wife of this your master, who is the God of Love. She was not born to Madanavega by Kaliṅgasenā, but, being of superhuman origin, was immediately substituted by the gods, who employed their deluding power, for the infant to which Kaliṅgasenā gave birth.[7] But the infant to which she gave birth was named Ityaka, and remained at the side of Madanavega, having been assigned to him by the Creator. So this Madanamañcukā is worthy to share the throne of her husband, for Śiva long ago granted her this honour as a boon, having been pleased with her asceticism.”

When the voice had said so much, it ceased, and the Vidyādharas were pleased, and praised the Queen Madanamañcukā.

Then, on an auspicious day, the great hermits sprinkled with water from many sacred bathing-places, brought in pitchers of gold, Naravāhanadatta seated on the imperial throne, while Madanamañcukā occupied the left half of it. And during the ceremony Sāntisoma, the domestic chaplain, was busily occupied, and the assembled cymbals of the heavenly nymphs resounded aloud,[8] and the murmur made by Brāhmans reciting prayers filled the ten points of the sky. Strange to say, when the water, made more purifying by holy texts, fell on his head, the secret defilement[9] of enmity was washed out from the minds of his foes. The Goddess of Fortune seemed to accompany in visible presence that water of consecration, under the impression that it came from the sea, and so was a connection of her own, and to join with it in covering the body of that king. A series of flower garlands, flung by the hands of the nymphs of heaven, falling on him, appeared like the Ganges spontaneously descending on his body with a full stream. Adorned with red unguent and valour, he appeared like the sun in the glory of rising, washed in the water of the sea.[10] And crowned with a garland of mandāra flowers, resplendent with glorious raiment and ornaments, having donned a heavenly diadem, he wore the majesty of Indra. And Queen Madanamañcukā, having been also anointed, glittered with heavenly ornaments at his side, like Śacī at the side of Indra.

And that day, though drums sounded like clouds, and flowers fell from the sky like rain, and though it was full[11] of heavenly nymphs like lightning gleams, was, strange to say, a fair one. On that occasion, in the city of the chief of the mountains, not only did beautiful Vidyādhara ladies dance, but creepers shaken by the wind danced also; and when cymbals were struck by minstrels at that great festival, the mountain seemed to send forth responsive strains from its echoing caves; and covered all over with Vidyādharas moving about intoxicated with the liquor of heavenly cordials it seemed to be itself reeling with wine; and Indra, in his chariot, having beheld the splendour of the coronation which has now been described, felt his pride in his own altogether dashed.

Naravāhanadatta, having thus obtained his long-desired inauguration as emperor, thought with yearning of his father.

And having at once taken counsel with Gomukha, and his other ministers, the monarch summoned Vāyupatha, and said to him:

“Go and say to my father:

‘Naravāhanadatta thinks of you with exceeding longing,’

and tell him all that has happened, and bring him here, and bring his queens and his ministers too, addressing the same invitation to them.”

When Vāyupatha heard this, he said: “I will do so,” and made for Kauśāmbī through the air.

And he reached that city in a moment, beheld with fear and astonishment by the citizens, as he was encircled by seventy million Vidyādharas. And he had an interview with Udayana, King of Vatsa, with his ministers and wives, and the king received him with appropriate courtesy.

And the Vidyādhara prince sat down and asked the king about his health, and said to him, while all present looked at him with curiosity:

“Your son, Naravāhanadatta, having propitiated Śiva, and beheld him face to face, and having obtained from him sciences difficult for enemies to conquer, has slain Mānasavega and Gaurīmuṇḍa in the southern division of the Vidyādhara territory, and conquered Mandaradeva who was lord in the northern division, and has obtained[12] the high dignity of emperor over all the kings of the Vidyādharas in both divisions, who acknowledge his authority; and has now gone through his solemn coronation on the Ṛṣabha mountain, and is thinking, King, with eager yearning of you and your queens and ministers. And I have been sent by him, so come at once; for fortunate are those who live to see their offspring elevate their race.”

When the King of Vatsa heard Vāyupatha say this, being full of longing for his son, he seemed like a peacock that rejoices when it hears the roaring of the rain-clouds. So he accepted Vāyupatha’s invitation, and immediately mounted a palankeen with him, and by the might of his sciences travelled through the air, accompanied by his wives and ministers, and reached that great heavenly mountain called Ṛṣabha. And there he saw his son on a heavenly throne, in the midst of the Vidyādhara kings, accompanied by many wives; resembling the moon reclining on the top of the eastern mountain, surrounded by the planetary host, and attended by a company of many stars. To the king the sight of his son in all his splendour was a shower of nectar, and when he was bedewed with it his heart swelled with joy, and he closely resembled the sea when the moon rises.

Naravāhanadatta, for his part, beholding that father of his after a long separation, rose up hurriedly and eager, and went to meet him with his train. And then his father embraced him, and folded him to his bosom, and he went through a second sprinkling,[13] being bathed in a flood of his father’s tears of joy. And Queen Vāsavadattā long embraced her son, and bathed him with the milk that flowed from her breasts at beholding him, so that he remembered his childhood. And Padmāvatī, and Yaugandharāyaṇa, and the rest of his father’s ministers, and his uncle Gopālaka, beholding him after a long interval, drank in with thirsty eyes his ambrosial frame, like partridges; while the king treated them with the honour which they deserved. And Kaliṅgasenā, beholding her son-in-law, and also her daughter, felt as if the whole world was too narrow for her, much less could her own limbs contain her swelling heart. And Yaugandharāyaṇa and the other ministers, beholding their sons, Hariśikha and the others, on whom celestial powers had been bestowed by the favour of their sovereign, congratulated them.[14]

And Queen Madanamañcukā. wearing heavenly ornaments, with Ratnaprabhā, Alaṅkāravatī, Lalitalocanā, Karpūrikā, Sāktiyaśas and Bhagīrathayaśas, and the sister of Ruciradeva, who bore a heavenly form, and Vegavatī, and Ajināvatī with Gandharvadattā, and Prabhāvatī and Ātmanikā and Vāyuvegayaśas, and her four beautiful friends, headed by Kālikā, and those five other heavenly nymphs, of whom Mandaradevī was the chief—all these wives of the Emperor Naravāhanadatta bowed before the feet of their father-in-law the King of Vatsa, and also of Vāsavadattā and Padmāvatī, and they in their delight loaded them with blessings, as was fitting.

And when the King of Vatsa and his wives had occupied seats suited to their dignity, Naravāhanadatta ascended his lofty throne. And Queen Vāsavadattā was delighted to see those various new daughters-in-law, and asked their names and lineage. And the King of Vatsa and his suite, beholding the godlike splendour of Naravāhanadatta, came to the conclusion that they had not been born in vain.

And in the midst of their great rejoicing[15] at the reunion of relations, the brave warder Rucideva entered and said:

“The banqueting hall is ready, so be pleased to come there.”

When they heard it they all went to that splendid banqueting hall. It was full of goblets made of various jewels, which looked like so many expanded lotuses, and strewn with many flowers, so that it resembled a lotus bed in a garden; and it was crowded with ladies with jugs full of intoxicating liquor, who made it flash like the nectar appearing in the arms of Garuḍa. There they drank wine that snaps those fetters of shame that bind the ladies of the harem; wine, the essence of love’s life, the ally of merriment. Their faces, expanded and red with wine, shone like the lotuses in the lake, expanded and red with the rays of the rising sun. And the goblets of the rosy hue of the lotus, finding themselves surpassed by the lips of the queens, and seeming terrified at toucing them, hid with their hue of wine.

Then the queens of Naravāhanadatta began to show signs of intoxication, with their contracted eyebrows and fiery eyes, and the period of quarrelling[16] seemed to be setting in; nevertheless they went thence in order to the hall[17] of feasting, which was attractive with its various viands provided by the magic power. It was strewed with coverlets, abounding in dishes, and hung with curtains and screens, full of all kinds of delicacies and enjoyments, and it looked like the dancing-ground of the goddesses of good fortune.

There they took their meal, and, the sun having retired to rest with the twilight on the western mountain, they reposed in sleeping pavilions. And Naravāhanadatta, dividing himself by his science into many forms, was present in the pavilions of all the queens. But in his true personality he enjoyed the society of his beloved Madanamañcukā, who resembled the night in being moon-faced, having eyes twinkling like stars, and being full of revelry. And the King of Vatsa too, and his train, spent that night in heavenly enjoyments, seeming as if they had been born again without changing their bodies. And in the morning all woke up, and delighted themselves in the same way with various enjoyments in splendid gardens and pavilions produced by magic power.

Then, after they had spent many days in various amusements, the King of Vatsa, wishing to return to his own city, went, full of affection, to his son, the king of all the Vidyādharas, who bowed humbly before him, and said to him:

“My son, who that has sense can help appreciating these heavenly enjoyments? But the love of dwelling in one’s mother-country naturally draws every man[18]; so I mean to return to my own city; but do you enjoy this fortune of Vidyādhara royalty, for these regions suit you as being half god and half man. However, you must summon me again some time, when a suitable occasion presents itself; for this is the fruit of this birth of mine, that I behold this beautiful moon of your countenance, full of nectar worthy of being drunk in with the eyes, and that I have the delight of seeing your heavenly splendour.”

When King Naravāhanadatta heard this sincere speech of his father, the King of Vatsa, he quickly summoned Devamāya, the Vidyādhara prince, and said to him in a voice half-choked with a weight of tears:

“My father is returning to his own capital with my mothers, and his ministers, and the rest of his train, so send on in front of him a full thousand bhāras[19] of gold and jewels, and employ a thousand Vidyādhara serfs to carry it.”

When Devamāya had received this order, given in the kind tones of his master, he bowed and said:

“Bestower of honour, I will go in person with my attendants to Kauśāmbī to perform this duty.”

Then the emperor sent Vāyupatha and Devamāya to attend on their journey his father and his followers, whom he honoured with presents of raiment and ornaments. Then the King of Vatsa and his suite mounted a heavenly chariot, and he went to his own city, after making his son, who followed him a long way, turn back. And Queen Vāsavadattā, whose longing regret rose at that moment with hundredfold force, turned back her dutiful son with tears, and, looking back at him, with difficulty tore herself away. And Naravāhanadatta, accompanied by his ministers, Gomukha and the rest, who had grown up with him from his youth, and with hosts of Vidyādhara kings, with his wives, and with Madanamañcukā at his side, in the perpetual enjoyment of heavenly pleasures was ever free from satiety.[20]

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Or “adorned with Viṣṇu’s Lakṣmī.” Here we have a pun, as she sprang from the sea.

[2]:

Herein he showed himself wiser than King Māndhātar, the hero of the first story in Ralston’s Tibetan Tales, who, after acquiring all earthly riches, aspired to the throne of Śakra, king of the gods. As soon as he had conceived this idea his good fortune came to an end (see Ralston, op. cit., p. 18, and also p. 36). The best-known example of a sudden fall after aspiring too high is, of course, Grimm’s tale of “The Fisherman and his Wife.” For numerous analogues see Bolte and Polfvka, op. cit., No. 19, vol. i, pp. 138-148.—n.m.p.

[3]:

See Vol. II, p.176n4. —n.m.p.

[4]:

Cf. the similar incident on p. 67 of this volume.—n.m.p.

[5]:

Of course, in the original the word expresses the idea of sprinkling with water.

[6]:

It may possibly mean, “land of the Siddhas.” In Chapter CVII the Siddhas are mentioned as directing Naravāhanadatta’s devotions on their holy mountain.

[7]:

See Vol. III, p. 131.—n.m.p.

[8]:

The corresponding line in the D. text reads: maṅgalyatūryanādeṣu sugīteṣu dyuyoṣitām —“at the beautiful songs of the heavenly nymphs accompanied by the auspicious sound of the (heavenly) musical instruments.” See Speyer, op. cit. p. 145.—n.m.p.

[9]:

I read vairamalaṃ. The reading in Brockhaus’ text is a misprint.

[10]:

Cf. Holinshed’s account of Richard II’s coronation:

“The Archbishop, having stripped him, first anointed his hands, after his head, breast, shoulders, and the joints of his arms, with the sacred oil, saying certain prayers, and in the meanwhile did the choir sing the anthem, beginning ‘Unxerunt regem Salomonem.’”

The above quotation comes from the Clarendon Press Edition of King Richard II, p. 137, sub calcem.

[11]:

I read vṛtam, which appears to be the reading of the three India Office MSS. and of the Sanskrit College MS. It is clear enough in No. 2166. In śl. 85 I think that the reading of MS. No. 3003, nānṛtyatkevalaṃ yāvad vātoddhūtalatā api, must be something near the truth, as yāval, in Brockhaus’ text, gives no meaning. (The Sanskrit College MS. gives Anṛtyannaiva vātena dhutā yāval latā api.) Of course the plural must be substituted for the singular. I have translated accordingly. Two MSS. have valgad for vallad in śl. 87.

[12]:

Two of the India Office MSS. and the Sanskrit College MS. read āsādya; the line appears to be omitted in the third.

[13]:

An allusion to the sprinkling at his coronation. The king “put him on his lap.”

[14]:

I read dṛṣṭvā prabhuprasādāptadivyatvān, which I find in two of the India Office MSS. No. 3003 has prata for prabhu.

[15]:

All the India Office MSS. read sangamahotsave. The Sanskrit College MS. reads bandhūnāṃ sangamotsave.

[16]:

This reading seems doubtful, as no further mention is made of the “quarrelling.” The D. text reads āsann akopakāle (see p. 524 of the second edition) instead of B.’s āsanne kopakāle’pi, thus the meaning is:

“The wives of Naravāhanadatta, though there was no opportunity then of being angry, had nevertheless contracted eyebrows and fiery eyes—for they were intoxicated.”

There is no gap, as Tawney supposed. The D. reading is undoubtedly correct. See further Speyer, op. cit., p. 145. —n.m.p.

[17]:

Literally, “ground.” No doubt they squatted on the ground at the feast as well as at the banquet—which preceded it, instead of following it—as in the days of Shakespeare.

[18]:

The King of Vatsa feels like Ulysses in the island of Calypso:

“ἤματα δ’ἂμ τέτρῃσι καὶ ἠϊόνεσσι καφίζων

δάκρυσι καὶ στοναχῇσι καὶ ἄλγεσι φυμὸν ἐρέχφων

πόντον ἐπ’ ἀτρύγετον δερκέσκετο δάκρυα λείβων.”

Odyssey, v, 156-158.

[19]:

A bhāra is 20 tulās.

[20]:

In the above chapter we have seen how, after the defeat of Mandaradeva, Naravāhanadatta proceeds with his coronation ceremony. As in the longest tale in the Nights, “King Omar bin al-Nu’uman and his Sons” (see Burton, vol. iii, p. 112), all the chief characters of the tale assemble, and, with a final blaze of glory, the curtain falls. Surely this should be the end of the whole work. The great object of the hero has been achieved, all the seemingly unsurmountable obstacles have been overcome, every enemy has been conquered, and every maiden has been won. Yet, to our great astonishment, we find three more complete Books before us. As we shall see in the “Terminal Essay,” the chief value of the Books is to clear up some of the unsolved mysteries of order and arrangement which have presented themselves in previous Books. —n.m.p.