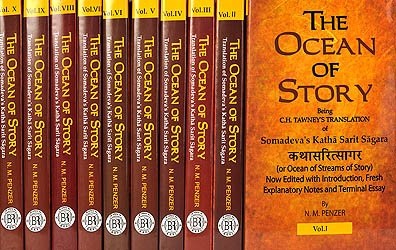

Kathasaritsagara (the Ocean of Story)

by Somadeva | 1924 | 1,023,469 words | ISBN-13: 9789350501351

This is the English translation of the Kathasaritsagara written by Somadeva around 1070. The principle story line revolves around prince Naravāhanadatta and his quest to become the emperor of the Vidhyādharas (‘celestial beings’). The work is one of the adoptations of the now lost Bṛhatkathā, a great Indian epic tale said to have been composed by ...

Chapter CIX

INVOCATION

MAY Gaṇeśa, who at night seems, with the spray blown forth from his hissing trunk uplifted in the tumultuous dance, to be feeding the stars, dispel your darkness!

[M] (main story line continued) Then, as the Emperor Naravāhanadatta was in his hall of audience on the mountain Govindakūṭa, a Vidyādhara named Amṛtaprabha came to him through the air, the same who had before saved him, when he was flung down by his enemy on the Mountain of Fire.

That Vidyādhara came and humbly made himself known, and, having been lovingly entertained by that emperor, said to him:

“There is a great mountain named Malaya in the southern region; and in a hermitage on it lives a great hermit named Vāmadeva. He, my liege, invites you to come to him alone for the sake of some important affair, and on this account he has sent me to you to-day. Moreover, you are my sovereign, won by previous merits; and therefore am I here; so come along with me; let us quickly go to that hermit in order to ensure your success!”

When that Vidyādhara had said this, Naravāhanadatta left his wives and forces there, and himself flew up into the air with that Vidyādhara, and in that way quickly reached the Malaya mountain, and approached the hermit Vāmadeva. And he beheld that hermit white with age, tall of stature, with eyeballs sparkling like bright jewels in the fleshless sockets of his eyes, the depository of the jewels of the emperor of the Vidyādharas, with his matted hair waving like creepers, looking like the Himālaya range accompanying the prince, to assist him in attaining success.

Then the prince worshipped the feet of that sage, and he entertained him, and said to him:

“You are the God of Love consumed long ago by Śiva, and appointed by him emperor of all the Vidyādhara chiefs, because he was pleased with Rati.[1] Now, I have in this my hermitage, within the deep recess of an inner cave, certain jewels, which I will point out to you, and you must seize them. For you will find Mandaradeva easy enough to conquer after you have obtained the jewels; and it was with this object that I invited you hither by the command of Śiva.”

When the hermit had said this to him, and had instructed him in the right method of procedure, Naravāhanadatta joyfully entered that cave. In it the hero overcame many and various obstacles, and then beheld a huge furious elephant charging him with a deep guttural roar. The king smote it on the forehead with his fist, and placed his feet on its tusks, and actively mounted the furious elephant.

And a bodiless voice came from the cave:

“Bravo, emperor! Thou hast won the jewel of the mighty elephant.”

Then he saw a sword looking like a mighty snake, and he fell upon it, and seized it, as if it were the locks of the Fortune of Empire.

Again a bodiless voice sounded in the cave:

“Bravo, conqueror of thy foes! Thou hast obtained the victorious sword-jewel.”

Then he obtained the moonlight-jewel and the wife-jewel, and the jewel of charms, named the destroying charm. And thus having achieved in all seven jewels (useful in time of need, and bestowers of majesty), taking into account the two first, the lake and the sandalwood-tree, he went out from that cave and told the hermit Vāmadeva that he had succeeded in accomplishing all his objects.

[also see notes on the seven jewels]

Then the hermit said lovingly to that emperor:

“Go, my son, now that you have obtained the jewels of a great emperor, and conquer Mandaradeva on the north side of Kailāsa, and enjoy the glorious fortune of the sovereignty of both sides of that mountain.”

When the hermit had said this to him, the successful emperor bowed before him, and went off through the air with Amṛtaprabha. And in a moment he reached his camp on Govindakūṭa, guarded by his mighty mother-in-law, Dhanavatī. Then those kings of the Vidyādharas that had sided with him, and his wives and his ministers, who were all watching for him, saw him, and welcomed him with delight. Then he sat down and they questioned him, and he told them how he had seen the hermit Vāmadeva, and how he had entered the cave, and how he had obtained the jewels. Then a great festival took place there, in which celestial drums were joyfully beaten, and the Vidyādharas danced, and people generally were drunk with wine.

And the next day, in a moment in which a malignant planet stood in the house of his foe, and one which argued his own success,[2] as a planet benignant to him, predominated over his enemy’s house, and which was fraught with every kind of prosperity, Naravāhanadatta performed the ceremonies for good fortune, and ascended that car made by Brahmā, which Śiva had bestowed on him, and set out with his army through the air, accompanied by his wives, to conquer Mandaradeva. And various heroes, his followers, marched surrounding him, and kings of the Gandharvas and chiefs of the Vidyādharas, fearless and faithful, obedient to the orders of the general, Hariśikha, and Caṇḍasiṃha, with his mother, the wise Dhanavatī, and the brave Piṅgalagāndhāra, and Vāyupatha the strong, and Vidyutpuñjā and Amitagati, and the lord of Kālakūṭa, and Mandara, and Mahādaṃṣṭra and his own friend Amṛtaprabha, and the hero Citrāṅgada, with Sāgaradatta—all these, and others who were there of the party of the slain Gaurīmuṇḍa, pressed eagerly after him, with their hosts, as he advanced intent on victory. Then the sky was obscured by his army, and the sun hid his face, as if for shame, somewhere or other, his brightness being eclipsed by the splendour of the monarch.

Then the emperor passed the Mānasa lake, haunted by troops of divine hermits, and left behind him Gaṇḍaśaila, the pleasure garden of the nymphs of heaven, and reached the foot of Mount Kailāsa, gleaming white like crystal, resembling a mass of his own glory.[3]

There he encamped on the bank of the Mandākinī; and while he was sitting there the wise chief of the Vidyādharas, named Mandara, came up to him, and addressed to him the following pleasing speech:

“Let your army halt here, King, on the bank of the river of the gods! It is not fitting that you should advance over this mountain, Kailāsa. For all sciences are destroyed by crossing this dwelling-place of Śiva. So you must pass to the other side of the mountain by the cave of Triśīrṣa. And it is guarded by a king named Devamāya, who is exceedingly haughty; so how can you advance farther without conquering him?”

When Mandara said this, Dhanavatī approved it, and Naravāhanadatta waited there for a day.

While he was there, he sent an ambassador to Devamāya with a conciliatory message, but he did not receive the order it conveyed in a conciliatory spirit. So the next day the emperor moved out against Devamāya, with all the allied kings, prepared for battle. And Devamāya too, when he heard it, marched out towards him to give battle, accompanied by numerous kings, Varāha, Vajramuṣṭi, and others, and followed by his army. Then there took place on Kailāsa a battle between those two armies, and while it was going on the sky was obscured by the chariots of the gods, who came to look on. Terrible was that thundercloud of war, awful with the dense hailstorm of many severed heads, and loud with the shouting of heroes. That Caṇḍasiṃha slew Varāha, the general of Devamāya, as he fought in the front rank, was in truth by no means wonderful; but it was strange that Naravāhanadatta, without employing any magic power, took captive Devamāya himself, when exhausted by the wounds he received from him in the combat. And when he was captured his army was broken, and fled, together with the great champions Vajramuṣṭi, Mahābāhu, Tīkṣṇadaṃṣṭra, and their fellows.

Then the gods in their chariots exclaimed: “Bravo! Bravo!”

And all present congratulated the victorious emperor. Then that mighty monarch consoled Devamāya, who was brought before him bound, and welcomed him kindly, and set him at liberty. But he, having been subdued by the emperor’s arm, humbly submitted to him, together with Vajramuṣṭi and the others.

Then, the battle having come to an end, that day passed away, and next morning Devamāya came to the place of audience, and stood by the side of the emperor, and when questioned by him about the cave of Triśīrṣa, which he wished to enter, related the following true history of it.

“In old time, my liege, the two sides of Mount Kailāsa, the north and the south side, formed different kingdoms, having been assigned to distinguished Vidyādharas. Then one, Ṛṣabha by name, propitiated Śiva with austerities, and was appointed, by that god, emperor over both of them. But one day he was passing over Kailāsa, to go to the northern side, and lost his magic science owing to the anger of Śiva, who happened to be below, and so fell from the sky.

Ṛṣabha again propitiated Śiva with severe asceticism, and the god again appointed him supreme sovereign of both sides; so he thus humbly addressed the god:

‘I am not permitted to pass over Kailāsa, so by what path am I to travel in order to be able to exercise my prerogatives on both sides of the mountain?’

When Śiva, the trident-bearing god, heard this, he cleft asunder Kailāsa, and made this cavelike opening for Ṛṣabha to pass to the northern side.

“Then Mount Kailāsa, having been pierced, was despondent, and addressed this petition to Śiva:

‘Holy one, this north side of me used to be inaccessible to mortals, but it has now been made accessible to them by this cave-passage; so provide that this law of exclusion be not broken.’

When Śiva had been thus supplicated by the mountain, he placed in the cave, as guards, elephants of the quarters, mighty basilisks,[4] and Guhyakas; and at its southern opening Kālarātri, the invincible Caṇḍikā.[5]

“When Śiva had thus provided for the guarding of the cave, he produced great jewels, and made this decree with regard to the cave:

‘This cave shall be open at both ends to anyone who has obtained the jewels, and is emperor over the Vidyādharas with their wives and their messengers,[6] and to those who may be appointed by him as sovereigns over the northern side of the mountain—by these, I say, it may be passed, but by no one else in the world.’

When the three-eyed god had made this decree, Ṛṣabha went on holding sway over the Vidyādharas, but in his pride made war on the gods, and was slain by Indra. This is the history, my liege, of the cave, named the cave of Triśīrṣa; and the cave cannot be passed by any but persons like yourself.

“And in course of time I, Devamāya, was born in the family of Mahāmāya, the keeper of the entrance of the cave.

And at my birth a heavenly voice proclaimed:

‘There is now born among the Vidyādharas a champion hard for his foes to conquer in fight; and he who shall conquer him shall be emperor over them; he shall be the master of this child now born, and shall be followed by him as a lord.’

I, that Devamāya, have been now conquered by you, and you have obtained the jewels, and are the mighty sole emperor of both sides of Mount Kailāsa—the lord of us all here. So now pass the cave of Triśīrṣa, and conquer the rest of your enemies.”

When Devamāya had told the story of the cave in these words the emperor said to him:

“We will march now and encamp for the present at the mouth of the cave, and tomorrow morning, after we have performed due ceremonies, we will enter it.”

When Naravāhanadatta had said this, he went and encamped with all those kings at the mouth of the cave. And he saw that underground passage with deep rayless cavity, looking like the birthplace of the sunless and moonless darkness of the day of doom.

And the next day he offered worship, and entered it in his chariot, with his followers, assisted by the glorious jewels, which presented themselves to him when he thought of them. He dispelled the darkness with the moonlight-jewel, the basilisks with the sandalwood-tree, the elephants of the quarters with the elephant-jewel, the Guhyakas with the sword-jewel, and other obstacles with other jewels; and so passed that cave with his army, and emerged at its northern mouth. And, coming out from the bowels of the cave, he saw before him the northern side of the mountain, looking like another world, entered without a second birth.

And then a voice came from the sky:

“Bravo, emperor! Thou hast passed this cave by means of the majesty conferred by the power of the jewels.”

Then Dhanavatī and Devamāya said to the emperor:

“Your Majesty, Kālarātri is always near this opening. She was originally created by Viṣṇu, when the sea was churned for the nectar, in order that she might tear in pieces the chiefs of the Dānavas, who wished to steal that heavenly drink. And now she has been placed here by Śiva to guard this cave, in order that none may pass it except those beings, like yourself, of whom we spoke before. You are our emperor and you have obtained the jewels, and have passed this cave; so, in order to gain the victory, you must worship this goddess, who is a meet object of worship.”

In such words did Dhanavatī and Devamāya address Naravāhanadatta, and so the day waned for him there. And the northern peaks of Kailāsa were reddened with the evening light, and seemed thus to foreshadow the bloodshed of the approaching battle. The darkness, having gained power, obscured the army of that king, as if recollecting its animosity, which was still fresh and new. And goblins, vampires, jackals and the sisterhood[7] of witches roamed about, as it were the first shoots of the anger of Kālarātri enraged on account of Naravāhanadatta having omitted to worship her. And in a moment the whole army of Naravāhanadatta became insensible, as if with sleep, but he alone remained in full possession of his faculties.

Then the emperor perceived that this was a display of power on the part of Kālarātri, angry because she had not been worshipped, and he proceeded to worship her with flowers of speech:

“Thou art the power of life, animating all creatures, of loving nature, skilful in directing the discus to the head of thy foes; thee I adore. Hail! thou, that under the form of Durgā dost console the world with thy trident and other weapons streaming with the drops of blood flowing from the throat of the slain Mahiṣa.[8] Thou art victorious, dancing with a skull full of the blood of Ruru[9] in thy agitated hand, as if thou wast holding the vessel of security of the three worlds. Goddess beloved of Śiva, with uplifted eyes, though thy name means the night of doom, still, with skull surmounted by a lighted lamp, and with a skull in thy hand, thou dost shine as if with the sun and moon.”

Though he praised Kālarātri in these words, she was not propitiated, and then he made up his mind to appease her by the sacrifice of his head; and he drew his sword to that purpose.

Then the goddess said to him:

“Do not act rashly, my son. Lo! I have been won over by thee, thou hero. Let this thy army be as it was before, and be thou victorious!”

And immediately his army awoke as it were from sleep. Then his wives, and his companions, and all the Vidyādharas, praised the might of that emperor! And the hero, having eaten and drunk and performed the necessary duties, spent that night, which seemed as long as if it consisted of a hundred watches instead of three.[10]

And the next morning he worshipped Kālarātri, and marched thence to engage Dhūmaśikha, who had barred his further advance with an army of Vidyādharas. Then the emperor had a fight with that king, who was the principal champion of Mandaradeva, of such a desperate character that the air was full of swords, the earth covered with the heads of warriors, and the only speech heard was the terrible cry of heroes shouting, “Slay! Slay!”

Then the emperor took Dhūmaśikha captive in that battle by force, and afterwards treated him with deference; and made him submit to his sway. And he quartered his army that night in his city, and the host seemed like fuel consumed with fire, as it had seen the extinction of Dhūmaśikha’s[11] pride.

And the next day, hearing from the scouts that Mandaradeva, having found out what had taken place, was advancing to meet him in fight, Naravāhanadatta marched out against him with the chiefs of the Vidyādharas, determined to conquer him. And after he had gone some distance he beheld in front of him the army of Mandaradeva, accompanied by many kings, attacking in order of battle. Then Naravāhanadatta, with the allied kings at his side, drew up his forces in an arrangement fitted to encounter the formation of his enemies, and fell upon his army.

Then a battle took place between those two armies, which imitated the disturbed flood of the ocean overflowing its bank at the day of doom. On one side were fighting Caṇḍasiṃha and other great champions, and on the other Kāñcanadaṃṣṭra and other mighty kings. And the battle waxed sore, resembling the rising of the wind at the day of doom, for it made the three worlds tremble, and shook the mountains. Mount Kailāsa, red on one side with the blood of heroes, as with saffron paint, and on the other of ashy whiteness, resembled the husband of Gaurī. That great battle was truly the day of doom for heroes, being grimly illuminated by innumerable orbs of the sun arisen in flashing sword-blades. Such was the battle that even Nārada and other heavenly beings, who came to gaze at it, were astonished, though they had witnessed the fights between the gods and the Asuras.

In this fight, which was thus terrible, Kāñcanadaṃṣṭra rushed on Caṇḍasiṃha, and smote him on the head with a formidable mace. When Dhanavatī saw that her son had fallen under the stroke of the mace, she cursed and paralysed both armies by means of her magic power. And Naravāhanadatta, on one side, in virtue of his imperial might,[12] and on the other side, Mandaradeva, were the only two that remained conscious. Then even the gods in the air fled in all directions, seeing that Dhanavatī, if angry, had power to destroy a world.

But Mandaradeva, seeing that the Emperor Naravāhanadatta, for his part, descended from his chariot, drawing the sword which was one of his imperial jewels, quickly met him. Then Mandaradeva, wishing to gain the victory by magic arts, assumed by his science the form of a furious elephant maddened with passion. When Naravāhanadatta, who was endowed with pre-eminent skill in magic, saw this, he assumed by his supernatural power the form of a lion.

Then Mandaradeva flung off the body of an elephant, and Naravāhanadatta abandoned that of a lion, and fought with him openly in his own shape.[13] Armed with sabres, and skilled in every elaborate trick and attitude of fence, they appeared like two actors skilled in gesticulation, engaged in acting a pantomime. Then Naravāhanadatta by a dexterous sleight forced from the grasp of Mandaradeva his sword, the material symbol of victory. And Mandaradeva, having been thus deprived of his sword, drew his dagger, but the emperor quickly made him relinquish that in the same way. Then Mandaradeva, being disarmed, began to wrestle with the emperor, but he seized him by the ankles, and laid him on the earth.

And then the sovereign set his foot on his enemy’s breast, and laying hold of his hair was preparing to cut off his head with his sword, when the maiden Mandaradevī, the sister of Mandaradeva, rushed up to him, and in order to prevent him said:

“When I saw you long ago in the wood of ascetics I marked you for my future husband, so do not, my sovereign, kill this brother of mine, who is your brother-in-law.”

When the resolute king had been thus addressed by that fair-eyed one he let go Mandaradeva, who was ashamed at having been conquered, and said to him:

“I set you at liberty; do not be ashamed on that account, Vidyādhara chief; victory and defeat in war bestow themselves on heroes with varying caprice.”

When the king said this, Mandaradeva answered him:

“Of what profit is my life to me, now that I have been saved in war by a woman? So I will go to my father in the wood where he is, and perform asceticism; you have been appointed emperor over both divisions of our territory here. Indeed this occurrence was foretold long ago to me by my father as sure to take place.”

When the proud hero had said this, he repaired to his father in the grove of ascetics.

Then the gods, that were present in the air on that occasion, exclaimed:

“Bravo, great emperor, you have completely conquered your enemies, and obtained sovereign sway!”

When Mandaradeva had gone, Dhanavatī, by her magic power, restored her own son, and both armies with him, to consciousness. So Naravāhanadatta’s followers, ministers and all, arose as it were from sleep, and, finding out that the foe had been conquered, congratulated Naravāhanadatta, their victorious master. And the kings of Mandaradeva’s party, Kāñcanadaṃṣṭra, Aśokaka, Raktākṣa, Kālajihva and the others, submitted to the sway of Naravāhanadatta. And Caṇḍasiṃha, when he saw Kāñcanadaṃṣṭra, remembered the blow of the mace which he received from him in fight, and was wroth with him, brandishing his good sword firmly grasped in his strong hand.

But Dhanavatī said to him:

“Enough of wrath, my beloved son! Who could conquer you in the van of battle? But I myself produced that momentary glamour, in order to prevent the destruction of both armies.”

With these words she pacified her son, and made him cease from wrath, and she delighted the whole army and the Emperor Naravāhanadatta[14] by her magic skill. And Naravāhanadatta was exceedingly joyful, having obtained the sovereignty of the north side of Kailāsa, the mountain of Śiva, a territory now free from the scourge of war, since the heroes who opposed him had been conquered, or had submitted, or fled, and that too with all his friends unharmed. Then shrill kettledrums were beaten for the great festival of his victory over his enemies,[15] and the triumphant monarch, accompanied by his wives and ministers, and girt with mighty kings, spent that day, which was honoured by the splendid dances and songs of the Vidyādhara ladies, in drinking wine, as it were the fiery valour of his enemies.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

The Sanskrit College MS. has Ratyā.

[2]:

For ātmasamarddhinā the India Office MS. No. 1882 has ātmasamṛddhinā; No. 2166 has samaṣṭinā, and No. 3003 agrees with Brockhaus’ text. So does the Sanskrit College MS.

[3]:

We have often had occasion to remark that the Hindu poets conceive of glory as white.

[4]:

See Sir Thomas Browne’s Vulgar Errors (Pseudodoxia Epidemica), Book III, chapter vii, and vol. iii,112nl. The point about the basilisk was that its glance was fatal, and this is how Tawney expresses the word dṛgviṣāhīndra. We have seen (Vol. II, p. 298) that dṛg-viṣa or dṛṣṭi-viṣa denotes “poison in a glance,” but in Hindu fiction this “fatal look” occurs in humans as well as in monsters, and is a power that can be acquired by prolonged austerities. (See Vol. IV, p. 232, and Vol. V, p. 123.) The idea is found in remote antiquity; thus, after the death of Osiris, Isis at last finds the box containing his body at Byblos. One of the king’s sons spies on her while she is embracing the dead body. Isis becomes aware of this and, turning round, kills him on the spot by a terrible look. See Budge, Osiris and the Egyptian Resurrection, vol. i, p. 7.—n.m.p.

[5]:

One of the śaktis (“energies”) of Śiva. Others are Durgā, Kālī, etc.

[6]:

Two of the India Office MSS. and the Sanskrit College MS. read cha chārāṇām for sadārāṇām. This would mean, I suppose, that the cave might be passed by all the scouts and ambassadors of the Vidyādharas.

[7]:

Or possibly “Gaṇas (Śiva’s attendants) and witches.”

[8]:

The giant slain by Durgā. See Wilkins, Hindu Mythology, p. 250.—n.m.p.

[9]:

See Vol. II, p.228n1.—n.m.p.

[10]:

The measures of time vary considerably, according to the different authorities. Yāmā is the word used here for “watch.” It occurs in the table as given in the Bhāgavata-purāṇa (iii. 2). For further details see Barnett, Antiquities of India, p. 219. —n.m.p.

[11]:

Dhūmaśikha, literally “the smoke-crested,” means “fire.”

[12]:

I read śaptvā, which I find in MSS. Nos. 1882 and 2166; the other has śasvā. I also find cakravartibalād in No. 1882 (with a short i), and this reading I have adopted. The Sanskrit College MS. seems to have śaptvā. In śl. 119, I think we ought to delete the ḥ in saṅgrāmaḥ. In 121 the apostrophe before gra-bhāsvaraḥ is useless and misleading. In 122 yad should be separated from vismayaṃ.

[13]:

Cf Vol. III, p. 195,195n1.

[14]:

All the India Office MSS. and the Sanskrit College MS. read cakravarti, with a short i.

[15]:

The India Office MSS. Nos. 1882 and 2166 and the Sanskrit College MS. read tāratūryaṃ. It makes the construction clearer, but no material difference in the sense.