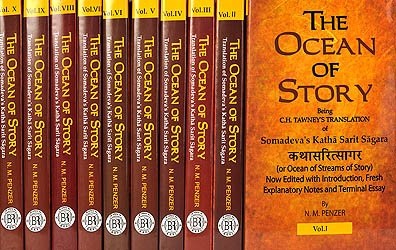

Kathasaritsagara (the Ocean of Story)

by Somadeva | 1924 | 1,023,469 words | ISBN-13: 9789350501351

This is the English translation of the Kathasaritsagara written by Somadeva around 1070. The principle story line revolves around prince Naravāhanadatta and his quest to become the emperor of the Vidhyādharas (‘celestial beings’). The work is one of the adoptations of the now lost Bṛhatkathā, a great Indian epic tale said to have been composed by ...

Chapter CVII

[M] (main story line continued) I THINK a hero’s prosperity must be unequal. Fate again and again severely tests firmness by the ordeals of happiness and misery; this explains why the fickle goddess kept uniting Naravāhanadatta to wife after wife, when he was alone in those remote regions, and then separating him from them.

Then, while he was residing on the mountain Ṛṣyamūka, his beloved Prabhāvatī came up to him, and said:

“It was owing to the misfortune of my not being present that Mānasavega carried you off on that occasion to the court, with the intention of doing you an injury. When I heard of it, I at once went there, and by means of my magic power I produced the delusion of the appearance of the god, and brought you here. For, though the Vidyādharas are mighty, their influence does not extend over this mountain, for this is the domain of the Siddhas.[1] Indeed even my science is of no avail here for that reason, and that grieves me, for how will you subsist on the products of the forest as your only food?”

When she had said this, Naravāhanadatta remained with her there, longing for the time of deliverance, thinking of Madanamañcukā. And on the banks of the sanctifying Pampā lake near that mountain he ate fruits and roots of heavenly flavour, and he drank the holy water of the lake, which was rendered delicious and fragrant by the fruits dropped from trees on its banks, as a relish to his meal of deer’s flesh.[2] And he lived at the foot of trees and in the interior of caverns, and so he imitated the conduct of Rāma, who once lived in the forests of that region. And Prabhāvatī, beholding there various hermitages once occupied by Rāma, told him the story of Rāma for his amusement.

166. Story of Rāma[3]

In this forest Rāma once dwelt, accompanied by Lakṣmaṇa, and waited on by Sītā, in the society of hermits, making to himself a hut at the foot of a tree. And Sītā, perfuming the whole forest with the perfume given her by Anasūyā, remained here in the midst of the hermits’ wives, wearing a robe of bark.

Here the Daitya Dundubhi was slain in a cave by Bāli, which was the original cause of the enmity between Bāli and Sugrīva. For Sugrīva, wrongly supposing that the Daitya had slain Bāli, blocked up the entrance of the cave with mountains, and went away terrified.

But Bāli broke through the obstruction and came out and banished Sugrīva, saying:

“This fellow imprisoned me in the cave because he wanted to get my kingdom.”

But Sugrīva fled, and came and established himself on this plateau of Ṛṣyamūka with the lords of the monkeys, of whom Hanumān was the chief.

Then Rāvaṇa came here, and beguiling the soul of Rāma with the phantom of a golden deer, he carried off his wife, the daughter of Janaka. Then the descendant of Raghu, who longed for news of Sītā, made an alliance with Sugrīva, who desired the slaughter of Bāli. And in order to let his might be known he cleft seven palm-trees here with an arrow, while the mighty Bāli with great difficulty cleft one of them. And then the hero went hence to Kiṣkindhya, and after slaying Bāli with a single arrow, which he launched as if in sport, gave his kingdom to Sugrīva.

Then the followers of Sugrīva, headed by Hanumān, went hence in every direction to gain information about Sītā. And Rāma remained here during the rainy season with the roaring clouds, which seemed to share his grief, shedding showery teardrops. At last Hanumān crossed the sea at the suggestion of Sampāti, and by great exertions obtained for Rāma the required information; whereupon he marched with the monkeys, and threw a bridge over the sea, and killed his enemy the lord of Lañkā, and brought back Queen Sītā in the flying chariot, passing over this place.

[M] (main story line continued)

“So, my husband, you also shall attain good fortune: successes come of their own accord to heroes who remain resolute in misfortunes.”

This and other such tales did Prabhāvatī tell, while she roamed about here and there for her pleasure with Naravāhanadatta.

And one day, as he was in the neighbourhood of Pampā, two Vidyādharīs, Dhanavatī and Ajināvatī, descended from heaven and approached him. These were the two ladies who carried him from the city of the Gandharvas to the city of Śrāvastī, where he[4] married Bhagīrathayaśas.

And while Ajināvatī was conversing with Prabhāvatī as an old friend, Dhanavatī thus addressed Naravāhanadatta:

“I long ago bestowed on you this daughter of mine, Ajināvatī, as far as promises could do it. So marry her; for the day of your exultation is nigh at hand.”

Prabhāvatī, out of love for her friend, and Naravāhanadatta both agreed to this proposal. Then Dhanavatī bestowed that daughter of hers, Ajināvatī, on that son of the King of Vatsa, with appropriate ceremonies. And she celebrated the great feast of her daughter’s wedding in such style that the glorious and heavenly preparations she had accumulated by means of her magic knowledge made it really beautiful.

Then the next day she said to Naravāhanadatta:

“My son, it will never do for you to remain long in a nondescript place like this; for the Vidyādharas are a deceitful race, and you have no business here. So depart now with your wife for your own city of Kauśāmbī; and I will come there with my son Caṇḍasiṃha and with the Vidyādhara chiefs that follow me, to ensure your success.”[5]

When Dhanavatī had said this, she mounted up into the sky, illuminating it, as it were, with moonlight, though it was day, by the gleam of her white body and raiment.

And Prabhāvatī and Ajināvatī carried Naravāhanadatta through the air to his city of Kauśāmbī. When he reached the garden of the city he descended from heaven into his capital, and was seen by his attendants.

And there arose there a cry from the people on all sides:

“We are indeed happy; here is the prince come back!”

Then the King of Vatsa, hearing of it, came there quickly in high delight, as if irrigated with a sudden shower of nectar, with Vāsavadattā and Padmāvatī, and the prince’s wives, Ratnaprabhā and the rest; and Yaugandharāyaṇa and the other ministers of the King of Vatsa, and Kaliṅgasenā and the prince’s own ministers, Gomukha and his fellows, approached him in order of precedence as eagerly as travellers make for a lake in the hot season. And they saw the hero, whose high birth qualified him for a lofty station, sitting between his two wives, like Kṛṣṇa between Rukmiṇī and Satyabhāmā. And when they saw him they hid their eyes with tears of joy, as if for fear lest they should leap out of their skins in their delight. And the King of Vatsa and his queens embraced after a long absence that son of theirs, and could not let him go, for they were, as it were, riveted to him by the hairs of their bodies erect from joy.[6]

Then a great feast began by beat of drum, and Vegavatī, the daughter of Vegavat and sister of Mānasavega, who was married to Naravāhanadatta, finding it all out by the might of her recovered science, came down to Kauśāmbī through the air, and fell at the feet of her father-in-law and mother-in-law, and prostrating herself before her husband, said to him:

“Auspicious sir, after I had become weak by my exertions on your behalf, I recovered my magic powers by self-mortification in a grove of ascetics, and now I have returned into your presence.”

When she had said this, she was welcomed by her husband and the others, and she repaired to her friends, Prabhāvatī and Ajināvatī.

They embraced her and made her sit between them.

And at that moment Dhanavatī, the mother of Ajināvatī, also arrived; and various kings of the Vidyādharas came with her, surrounded by their forces, that hid the heaven like clouds: her own heroic son, the strong-armed Caṇḍasiṃha, and a powerful relation of hers, Amitagati by name, and Piṅgalagāndhāra, the mighty father of Prabhāvatī, and Vāyupatha, the president of the court, who had previously declared himself on Naravāhanadatta’s side, and the heroic King Hemaprabha, the father of Ratnaprabhā, accompanied by his son Vajraprabha and followed by his army. And Sāgaradatta, the King of the Gandharvas, came there, accompanied by his daughter Gandharvadattā, and by Citrāṅgada. And when they arrived, they were becomingly honoured by the King of Vatsa and his son, and sat in due order on thrones.

And immediately King Piṅgalagāndhāra said to his son-in-law Naravāhanadatta, as he was in the hall of assembly:

“King, you have been appointed by the god[7] emperor over us all, and it is owing to our great love for you that we have all come to you. And Queen Dhanavatī here, your mother-in-law, a strict votary, possessing divine knowledge, wearing the rosary and the skin of the black antelope, like an incarnation of Durgā, or Sāvitrī, having acquired magic powers, an object of reverence to the noblest Vidyādharas, has made herself ready to protect you; so you are certain to prosper in your undertaking. But listen to what I am about to say. There are two divisions of the Vidyādhara territory[8] on the Himālayas here, the northern and the southern, both extending over many peaks of that range; the northern division is on the other side of Kailāsa, but the southern is on this side of it. And this Amitagati here has just performed a difficult penance on Mount Kailāsa, in order to obtain the sovereignty over the northern division, and propitiated Śiva.

And Śiva made this revelation to him,

‘Naravāhanadatta thy emperor will accomplish thy desire,’

so he has come here to you. In that division there is a chief monarch, named Mandaradeva, who is evilly disposed, but, though mighty, he will be easy for you to conquer, when you have obtained the sciences peculiar to the Vidyādharas.

“But the king named Gaurīmuṇḍa, who rules in the midst of the southern division, is evil-minded and exceedingly hard to conquer on account of the might of his magic science. Moreover, he is a great friend of your enemy Mānasavega. Until he is overcome your undertaking will not prosper; so acquire as quickly as possible great and transcendent power of science.”

When Piṅgalagāndhāra had said this, Dhanavatī spake:

“Good, my son! it is as this king tells thee. Go hence to the land of the Siddhas[9] and propitiate the god Śiva, in order that thou mayest obtain the magic sciences, for how can there be any excelling without his favour? And these kings will be assembled there to protect thee.”

Then Citrāṅgada said:

“It is even so; but I will advance in front of all: let us conquer our enemies.”

Then Naravāhanadatta determined to do as they had advised, and he performed the auspicious ceremony before setting out, and bowed at the feet of his tearful parents and other superiors, and received their blessing, and then ascended with his wives and ministers in a splendid palankeen provided by the skill of Amitagati, and started on his expedition, obscuring the heaven with his forces, that resembled the water of the sea raised by the wind at the end of a kalpa, as it were proclaiming, by the echoes of his army’s roar on the limits of the horizon, that the emperor of the Vidyādharas had come to visit them.

And he was rapidly conducted by the king of the Gandharvas and the chiefs of the Vidyādharas and Dhanavatī to that mountain, which was the domain of the Siddhas. There the Siddhas prescribed for him a course of self-mortification, and he performed asceticism by sleeping on the ground, bathing in the early morning, and eating fruits. And the kings of the Vidyādharas remained surrounding him on every side, guarding him unweariedly day and night. And the Vidyādhara princesses, contemplating him eagerly while he was performing his penance, seemed with the gleams of their eyes to clothe him in the skin of a black antelope. Others showed by their eyes turned inwards out of anxiety for him, and their hands placed on their breasts, that he had at once entered their hearts.

And five more noble maidens of the Vidyādhara race, beholding him, were inflamed with the fire of love, and made this agreement together:

“We five friends must select this prince as our common husband, and we must marry him at the same time, not separately; if one of us marries him separately, the rest must enter the fire on account of that violation of friendship.”

While the heavenly maidens were thus agitated at the sight of him, suddenly great portents manifested themselves in the grove of ascetics.

A very terrible wind blew, uprooting splendid trees, as if to show that even thus in that place should heroes fall in fight; and the earth trembled as if anxious as to what all that could mean, and the hills cleft asunder, as if to give an opening for the terrified to escape, and the sky, rumbling awfully, though cloudless,[10] seemed to say:

“Ye Vidyādharas, guard, guard to the best of your power, this emperor of yours.”

And Naravāhanadatta, in the midst of the alarm produced by these portents, remained unmoved, meditating upon the adorable three-eyed god; and the heroic kings of the Gandharvas and lords of the Vidyādharas remained guarding him, ready for battle, expecting some calamity; and they uttered war-cries, and agitated the forest of their lithe swords, as if to scare away the portents that announced the approach of evil.

And the next day after this the army of the Vidyādharas was suddenly seen in the sky, dense as a cloud at the end of the kalpa, uttering a terrible shout.

Then Dhanavatī, calling to mind her magic science, said:

“This is Gaurīmuṇḍa, come with Mānasavega.”

Then those kings of the Vidyādharas and the Gandharvas raised their weapons, but Gaurīmuṇḍa, with Mānasavega, rushed upon them, exclaiming:

“What right has a mere man to rank with beings like us? So I will to-day crush your pride, you sky-goers that take part with him.”

When Gaurīmuṇḍa said this, Citrāṅgada rushed upon him angrily, and attacked him.

And King Sāgaradatta, the sovereign of the Gandharvas, and Caṇḍasiṃha, and Amitagati, and King Vāyupatha, and Piṅgalagāndhāra, and all the chiefs of the Vidyādharas, great heroes all, rushed upon the wicked Mānasavega, roaring like lions, followed by the whole of their forces. And right terrible was that storm of battle, thick with the clouds of dust raised by the army, with the gleams of weapons for flashes of lightning, and a falling rain of blood. And so Citrāṅgada and his friends made, as it were, a great sacrifice for the demons, which was full of blood for wine, and in which the heads of enemies were strewn as an offering. And streams of gore flowed away, full of bodies for crocodiles, and floating weapons for snakes, and in which marrow intermingled took the place of cuttlefish-bone.

Then Gaurīmuṇḍa, as his army was slain, and he himself was nigh to death, called to mind the magic science of Gaurī, which he had formerly propitiated and made well disposed to him; and that science appeared in visible form with three eyes, armed with the trident,[11] and paralysed the chief heroes of Naravāhanadatta’s army. Then Gaurīmuṇḍa, having regained strength, rushed with a loud shout towards Naravāhanadatta, and fell on him to try his strength in wrestling. And being beaten by him in wrestling, the cogging Vidyādhara again summoned up that science, and by its power he seized his antagonist in his arms and flew up to the sky. However, he was prevented by the might of Dhanavatī’s science from slaying the prince, so he flung him down on the Mountain of Fire.

But Mānasavega seized his comrades, Gomukha and the rest, and flew up into the sky with them, and flung them at random in all directions. But, after they had been flung up, they were preserved by a science in visible shape employed by Dhanavatī, and placed in different spots on the earth.

And that science comforted those heroes, one by one, saying to them,

“You will soon recover that master of yours, successful and flourishing,”

and having said this it disappeared.

Then Gaurīmuṇḍa went back home with Mānasavega, thinking that their side had been victorious.

But Dhanavatī said:

“Naravāhanadatta will return to you after he has attained his object; no harm will befall him.”

And thereupon the lords of the Gandharvas and the princes of the Vidyādharas, Citrāṅgada and the others, flung off their paralysing stupor, and went for the present to their own abodes. And Dhanavatī took her daughter Ajināvatī, with all her fellow-wives, and went to her own home.

Mānasavega, for his part, went and said to Madanamañcukā:

“Your husband is slain; so you had better marry me.”

But she, standing in front of him, said to him, laughing:

“He will slay you; no one can slay him, as he has been appointed by the god.”

But when Naravāhanadatta was being hurled down by his enemy on the Mountain of Fire, a certain heavenly being came there, and received him; and after preserving his life he took him quickly to the cool bank of the Mandākinī.

And when Naravāhanadatta asked him who he was, he comforted him, and said to him:

“I, Prince, am a king of the Vidyādharas named Amṛtaprabha, and I have been sent by Śiva on the present occasion to save your life. Here is the mountain of Kailāsa in front of you, the dwelling-place of that god; if you propitiate Śiva there, you will obtain unimpeded felicity. So, come, I will take you there.”

When that noble Vidyādhara had said this, he immediately conveyed him there, and took leave of him, and departed.

But Naravāhanadatta, when he had reached Kailāsa, propitiated with asceticism Gaṇeśa, whom he found there in front of him. And, after obtaining his permission, he entered the hermitage of Śiva, emaciated with self-mortification, and he beheld Nandin at the door. He devoutly circumambulated him, and then Nandin said to him:

“Thou hast well-nigh attained all thy ends; for all the obstacles that hindered thee have now been overcome; so remain here, and perform a strict vow of asceticism that will subdue sin, until thou shalt have propitiated the adorable god; for success depends on purity.”

When Nandin had said this, Naravāhanadatta began a severe course of penance there, living on air, and meditating on the god Śiva and the goddess Pārvatī.

And the adorable god Śiva, pleased with his asceticism, granted him a vision of himself, and, accompanied by the goddess, thus spake to the prince, as he bent before him:

“Become now emperor over all the Vidyādharas, and let all the most transcendent sciences be immediately revealed to thee! By my favour thou shalt become invincible by thy enemies, and, as thou shalt be proof against cut or thrust, thou shalt slay all thy foes. And when thou appearest, the sciences of thy enemies shall be of no avail against thee. So go forth: even the science of Gaurī shall be subject to thee.”

When Śiva and Gaurī had bestowed these boons on Naravāhanadatta, the god also gave him a great imperial chariot, in the form of a lotus, made by Brahmā.

Then all the sciences presented themselves to the prince in bodily form, and expressed their desire to carry out his orders by saying:

“What do you enjoin on us, that we may perform it?”

Accordingly Naravāhanadatta, having obtained many boons, bowed before the great god, and ascended the heavenly lotus chariot, after he had received permission from him to depart, and went first to the city of Amitagati, named Vakrapura; and as he went, the sciences showed him the path, and the bards of the Siddhas sang his praises. And Amitagati, seeing him from a distance, as he came along through the air, mounted on a chariot, advanced to meet him and bowed before him, and made him enter his palace. And when he described how he had obtained all these magic powers, Amitagati was so delighted that he gave him as a present his own daughter named Sulocanā. And with her, thus obtained, like a second imperial fortune of the Vidyādhara race, the emperor joyfully passed that day as one long festival.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

See Vol. II, pp. 67,61n1 and 75.

[2]:

Here two of the India Office MSS. read māṃsopadaṃśam, the third māṃsopadeśaṃ.

[3]:

This is merely a very brief résumé of the second part of Book II (Ayodhyā-kāṇḍa) of the Rāmāyaṇa. For an English verse translation see that by R. T. H. Griffith, 5 vols., London and Benares, 1870-1874; and for a prose translation that by M. N. Dutt, 7 vols., Calcutta, 1892-1894.—n.m.p.

[4]:

Dr Kern reads tena for yena. His conjecture is confirmed by the three India Office MSS. and the Sanskrit College MS.

[5]:

I have adopted Dr Kern’s conjecture of saha for saki and separated with him abhyudayāyate into two words, abhyudayāya te. I find that his conjecture as to saha is confirmed by the three India Office MSS.

[6]:

See Vol. I, p.120nl.—n.m.p.

[7]:

Probably devanirmitaḥ should be one word.

[8]:

See Vol. IV, pp. 1 and 2. —n.m.p.

[9]:

In Sanskrit Siddhakṣetra.

[10]:

Perhaps we may compare Virgil, Georgies, i, 487, and Horace, Odes, i, 34, 35, and Virgil, Æneid, vii, 141, with the passages there quoted by Forbiger. But MSS. Nos. 1882 and 2166 read udbhūta.

[11]:

It is clear that the goddess did not herself appear, so trinetrā is not a proper name, unless we translate the passage “armed with the trident of Gaurī.”