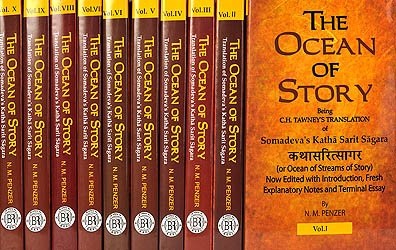

Kathasaritsagara (the Ocean of Story)

by Somadeva | 1924 | 1,023,469 words | ISBN-13: 9789350501351

This is the English translation of the Kathasaritsagara written by Somadeva around 1070. The principle story line revolves around prince Naravāhanadatta and his quest to become the emperor of the Vidhyādharas (‘celestial beings’). The work is one of the adoptations of the now lost Bṛhatkathā, a great Indian epic tale said to have been composed by ...

Chapter CV

INVOCATION

MAY Śiva, the granter of boons, who, when pleased, bestowed on Umā half his own body, grant you your desire!

May the vermilion-stained trunk which Gaṇeśa at night throws up in the dance, and so seems to furnish the moon-umbrella with a coral handle, protect you!

[M] (main story line continued) Then Naravāhanadatta, son of the King of Vatsa, possessing as his wives those various ladies, the most beautiful in the three worlds, and Madanamañcukā as his head-queen, dwelt with Gomukha and his other ministers in Kauśāmbī, having his every want supplied by his father’s magnificent resources. His days passed pleasantly in dancing, singing and conversation, and were enlivened by the exquisite enjoyment of the society of the ladies whom he loved.

Then it happened one day that he could not find his principal charmer Madanamañcukā anywhere in the female apartments, nor could her attendants find her either.[1] When he could not see his beloved, he became pale from grief, as the moon loses its beauty in the morning, by being separated from the night.

And he was distracted by an innumerable host of doubts, saying to himself:

“I wonder whether my beloved has hidden herself somewhere to ascertain my sentiments towards her; or is she indignant with me for some trifling fault or other; or is she concealed by magic, or has she been carried off by someone?”

When he had searched for her, and could not find her anywhere, he was consumed by violent grief for his separation from her, which raged in his bosom like a forest conflagration. His father, the King of Vatsa, who came to visit him as soon as he knew the state of affairs, and his mother, ministers and servants were all beside themselves. The pearl necklace, sandalwood ointment, the rays of the moon, lotus fibres and lotus leaves did not alleviate his torture, but rather increased it. As for Kaliṅgasenā, when she was suddenly deprived of that daughter she was confounded like a Vidyādharī who has lost her magic power.

Then an aged female guardian of the women’s apartments said in the presence of Naravāhanadatta, so that all there heard:

“Long ago, that young Vidyādhara, named Mānasavega, having beheld Madanamañcukā, when she was a maiden, on the top of the palace, suddenly descended from heaven, and approaching Kaliṅgasenā, told her his name, and asked her to give him her daughter. When Kaliṅgasenā refused, he went as he came. But why should he not have now come secretly and carried her off by his magic power? It is of course true that heavenly beings do not carry off the wives of others; on the other hand, who that is blinded by passion troubles himself about the right or wrong of an action?”

When Naravāhanadatta heard this, his heart was overwhelmed with anger, impatience and the sorrow of bereavement, and became like a lotus in the waves.

Then Rumaṇvat said:

“This palace is guarded all round, and it is impossible to enter or go out from it, except through the air. Moreover, by the favour of Śiva no misfortune can befall her; so we may be certain that she has hidden herself somewhere, because her affection has been wounded. Listen to a story which will make this clear.

164. Story of Sāvitrī and Aṅgiras

Once upon a time a hermit, named Aṅgiras, asked Aṣṭāvakra for the hand of his daughter Sāvitrī. But Aṣṭāvakra would not give him his daughter Sāvitrī, though he was an excellent match, because she was already betrothed to someone else. Then Aṅgiras married Aśrutā, his brother’s daughter, and lived a long time with her as his wife in great happiness; but she was well aware that he had previously been in love with Sāvitrī.

One day that hermit Aṅgiras remained muttering for a long time in an inaudible voice. Then his wife Aśrutā asked him again and again lovingly:

“Tell me, my husband, why do you remain so long fixed in thought?”

He said:

“My dear, I am meditating on the Sāvitrī”;

and she, thinking that he meant Sāvitrī, the hermit’s daughter, was vexed in soul.

She said to herself, “He is miserable,” so she went off to the forest, determined to abandon the body. And after she had prayed that good fortune might attend her husband, she fastened a rope round her neck.

And at that moment Gāyatrī appeared, with rosary of Akṣa beads and ascetic’s pitcher, and said to her:

“Daughter, do not act rashly! Your husband was not thinking of any woman, he was meditating on me, the holy Sāvitrī”;

and with these words she freed her neck from the noose. And the goddess, merciful to her votaries, having thus consoled her, disappeared. Then her husband Aṅgiras, searching for her, found her in the wood, and brought her home. So you see that women in this world cannot endure the wounding of their affections.

[M] (main story line continued)

“So you may be certain that this wife of the prince is angry on account of some trifling injury, and is hidden somewhere in this place; for she is under the protection of Śiva, and we must again search for her.”

When Rumaṇvat said this, the sovereign of Vatsa said:

“It must be so; for no misfortune can befall her, inasmuch as a heavenly voice said, ‘This Madanamañcukā is an incarnation of Rati, appointed by the god to be the wife of Naravāhanadatta, who is an emanation of the God of Love, and he shall rule the Vidyādharas with her as his consort for a kalpa of the gods,’ and this utterance cannot be falsified by the event. So let her be carefully looked for.”

When the king himself said this, Naravāhanadatta went out, though he was in such a miserable state.

But, however much he searched for her, he could not find her, so he wandered about in various parts of the grounds, like one distracted.

When he went to her dwelling, the rooms with closed doors seemed as if they had shut their eyes in despair at beholding his grief; and when he went about in the groves asking for her, the trees, agitating their shoots like hands, seemed to say: “We have not seen your beloved.”

When he searched in the gardens, the sārasa birds, flying up to the sky, seemed to tell him that she had not gone that way. And his ministers Marubhūti, Hariśikha, Gomukha and Vasantaka wandered about in every direction to find her.

In the meanwhile an unmarried Vidyādharī, of the name of Vegavatī, having beheld Madanamañcukā in her splendid and glorious beauty, deliberately took her shape, and came and stood alone in the garden under an aśoka tree. Marubhūti saw her, as he was roaming about in search of the queen, and she seemed at once to extract the dart from his pierced heart.

And in his joy he went to Naravāhanadatta, and said to him:

“Cheer up, I have seen your beloved in the garden.”

When he said this, Naravāhanadatta was delighted, and immediately went with him to that garden.

Then, exhausted with long bereavement, he beheld that semblance of Madanamañcukā with feelings like those with which a thirsty traveller beholds a stream of water.

And the moment he beheld her, the much-afflicted prince longed to embrace her, but she, being cunning, and wishing to be married by him, said to him:

“Do not touch me now; first hear what I have to say.

Before I married you, I prayed to the Yakṣas to enable me to obtain you, and said:

‘On my wedding-day I will make offerings to you with my own hand.’

But, my beloved, when my wedding-day came, I forgot all about them. That enraged the Yakṣas, and so they carried me off from this place.

And they have just brought me here, and let me go, saying:

‘Go and perform over again that ceremony of marriage, and make oblations to us, and then repair to your husband; otherwise you will not prosper.’

So marry me quickly, in order that I may offer the Yakṣas the worship they demand, and then fulfil all your desire.”

When Naravāhanadatta heard that, he summoned the priest Śāntisoma and at once made the necessary preparations, and immediately married the supposed Madanamañcukā, who was no other than the Vidyādharī Vegavatī, having been for a short time quite cast down by his separation from the real one. Then a great feast took place there, full of the clang of cymbals, delighting the King of Vatsa, gladdening the queens, and causing joy to Kaliṅgasenā. And the supposed Madanamañcukā, who was really the Vidyādharī Vegavatī, made with her own hand an offering of wine, flesh and other dainties to the Yakṣas. Then Naravāhanadatta, remaining with her in her chamber, drank wine with her in his exultation, though he was sufficiently intoxicated with her voice. And then he retired to rest with her who had thus changed her shape, as the sun with the shadow.

And she said to him in secret:

“My beloved, now that we have retired to rest, you must take care not to unveil my face suddenly and look at me while asleep.”[2]

When the prince heard this, he was filled with curiosity to think what this might be, and the next day he uncovered her face while she was asleep and looked at it, and lo! it was not Madanamañcukā, but someone else, who, when asleep, had lost the power of disguising her appearance by magic.[3]

Then she woke up while he was sitting by her awake. And he said to her:

“Tell me, who are you?”

And the discreet Vidyādharī, seeing him sitting up awake, and being conscious that she was in her own shape and that her secret was discovered, began to tell her tale, saying:

“Listen, my beloved, I will now tell you the whole story.

“There is in the city of the Vidyādharas a mountain of the name of Āṣāḍhapura. There dwells a chief of the Vidyādharas, named Mānasavega, a prince puffed up with the might of his arm, the son of King Vegavat. I am his younger sister, and my name is Vegavatī. And that brother of mine hated me so much that he was not willing to bestow on me the sciences. Then I obtained them, though with difficulty, from my father, who had retired to a wood of ascetics, and, thanks to his favour, I possess them of greater power than any other of our race. I myself saw the wretched Madanamañcukā, in the palace of Mount Āṣāḍha, in a garden, surrounded by sentinels. I mean your beloved, whom my brother has carried off by magic, as Rāvaṇa carried off the afflicted Sītā, the wife of Rāmabhadra. And as the virtuous lady repels his caresses, he cannot subdue her to his will, for a curse has been laid upon him that will bring about his death if he uses violence to any woman.

“So that wicked brother of mine made use of me to try to talk her over; and I went to that lady, who could do nothing but talk of you. And in my conversation with her that virtuous lady mentioned your name,[4] which was like a command from the God of Love, and thus my mind then became fixed upon you alone.

And then I remembered an announcement which Pārvatī made to me in a dream, much to the following effect:

‘You shall be married to that man, the mere hearing of whose name overpowers you with love.’

When I had called this to mind, I cheered up Madanamañcukā, and came here in her form, and married myself to you by an artifice. So come, my beloved, I am filled with such compassion for your wife Madanamañcukā that I will take you where she is; for I am the devoted servant of my rival, even as I am of you, because you love her. For I am so completely enslaved by love for you that I am rendered quite unselfish by it.”

When Vegavatī had said this, she took Naravāhanadatta, and by the might of her science flew up with him into the sky during the night. And next morning, while she was slowly travelling through the heaven, the attendants of the husband and wife were bewildered by their disappearance.

And when the King of Vatsa came to hear of it, he was immediately, as it were, struck by a thunderbolt, and so were Vāsavadattā, Padmāvatī and the rest. And the citizens, and the king’s ministers Yaugandharāyaṇa and the others, together with their sons Marubhūti and the rest, were altogether distracted.

Then the hermit Nārada, surrounded with a circle of light, descended there from heaven, like a second sun.

The King of Vatsa offered him the arghya, and the hermit said to him:

“Your son has been carried off by a Vidyādharī to her country, but he will soon return; and I have been sent by Śiva to cheer you up.”

And after this prelude he went on to tell the king of Vegavatī’s proceedings exactly as they took place. Then the king recovered his spirits and the hermit disappeared.

In the meanwhile Vegavatī carried Naravāhanadatta through the air to the mountain Āṣāḍhapura. And Mānasavega, hearing of it, hastened there to kill them both. Then Vegavatī engaged with her brother in a struggle which was remarkable for a great display of magic power; for a woman values her lover as her life, and much more than her own relations. Then she assumed by the might of her magic a terrible form of Bhairava, and at once striking Mānasavega senseless, she placed him on the mountain of Agni. And she took Naravāhanadatta, whom at the beginning of the contest she had deposited in the care of one of her sciences,[5] and placed him in a dry well in the city of the Gandharvas, to keep him.

And when he was there, she said to him:

“Remain here a little while, my husband; good fortune will befall you here. And do not despond in your heart, O man appointed to a happy lot! for the sovereignty over all the Vidyādharas is to be yours. But I must leave this for the present, to appease my sciences, impaired by my resistance to my elder brother. However, I will return to you soon.”

When the Vidyādharī Vegavatī had said this, she departed somewhere or other.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

I adopt the reading of MSS. Nos. 1882 and 2166, parijanaḥ. This seems to make better sense.——See Vol. VII, p. 195.—n.m.p.

[2]:

This bears a slight resemblance to the story of Psyche.——See Vol. II, p. 252 et seq., for the nuptial taboo.—n.m.p.

[3]:

Cf. Vol. III, p. 123.—N.M.P.

[4]:

I read with MSS. Nos. 1882 and 2166 tvadnāmnyudīrite; No. 3003 reads tvattrāsyudīrite. This seems to point to the same reading, which agrees with śl. 74a. It is also found in a MS. lent me by the Principal of the Sanskrit College.

[5]:

Two of the India Office MSS. read haste. So also the Sanskrit College MS.