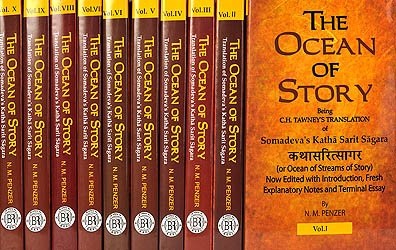

Kathasaritsagara (the Ocean of Story)

by Somadeva | 1924 | 1,023,469 words | ISBN-13: 9789350501351

This is the English translation of the Kathasaritsagara written by Somadeva around 1070. The principle story line revolves around prince Naravāhanadatta and his quest to become the emperor of the Vidhyādharas (‘celestial beings’). The work is one of the adoptations of the now lost Bṛhatkathā, a great Indian epic tale said to have been composed by ...

Chapter CIV

INVOCATION

MAY that Gaṇeśa, whom, when dancing in the twilight intervals between the Yugas, all the worlds seem to imitate by rising and falling, protect you! May the blaze of the eye in the forehead of Śiva, who is smeared with the beautiful red dye used by Gaurī for adorning her feet, befriend you for your happiness!

We adore the goddess Sarasvatī, taking form as speech to our heart’s delight, the bee that dwells in the lotus on the lake of the mighty poet’s mind.[1]

[M] (main story line continued) Then Naravāhanadatta, the son of the King of Vatsa, afflicted with separation, being without Madanamañcukā, roamed about on those lower slopes of Mount Malaya, and in its bordering forests, which were in all the beauty of spring, but found joy nowhere.[2] The cluster of mango-blossoms, though in itself soft, yet seeming, on account of the bees[3] that settled on it, like the pliant bow of the God of Love, cleft his heart. And the song of the cuckoo, though sweet in itself, was hard to bear, and gave pain to his ears, as it seemed to be harsh with the reproachful utterances of Māra.[4] And the wind of the Malaya mountain, though in itself cool, yet being yellow with the pollen of flowers, and so looking like the fire of Kāma, seemed to burn him, when it fell on his limbs. So he slowly left that region, being, so to speak, drummed out of it by those groves that were all resonant with the hum of bees.

And gradually, as he journeyed on, with the deity for his guide, by a path that led towards the Ganges, he reached the bank of a lake in a neighbouring wood. And there he beheld two young Brāhmans of handsome appearance, sitting at the foot of a tree, engaged in unrestrained conversation.

And when they saw him, they thought he was the God of Love, and they rose up and, bowing before him, said:

“All hail to thee, adorable god of the flowery bow! Tell us why thou wanderest here alone without that fragrant artillery of thine, and where is that Rati, thy constant companion?”

When the son of the King of Vatsa heard that, he said to those Brāhmans:

“I am not the god Kāma, I am a mere mortal; but I have indeed lost my Rati.”[5]

When the prince had said this, he told his history, and said to those Brāhmans:

“Who are you, and of what kind is this talk that you two are carrying on here?”

Then one of those young Brāhmans said to him respectfully:

“King, how can we tell our secret in the presence of a man of your worth? Nevertheless, out of respect for your command, I will tell our history. Give ear!

“There is in the territory of Kaliṅga a city of the name of Śobhāvatī, which has never been entered by the demon Kali, nor touched by evil-doers, nor seen by a foreign foe: such has it been made by the Creator. In it there was a wise and rich Brāhman, of the name of Yaśaskara, who had offered many sacrifices, and he had an excellent wife named Mekhalā. I was born to them as an only son, when they were already in middle life, and I was in due course reared up by them, and invested with the sacrificial thread.[6]

“Then, while as a boy I was studying the Vedas, there arose a mighty famine in that land, owing to drought. So my father and my mother went off with me to a city named Viśālā, taking with them their wealth and their servants. In that city, in which fortune and learning dwelt together, having laid aside their long feud, my father established himself, having had a house given him by a merchant, who was a friend of his. And I dwelt there in the house of my preceptor, engaged in the acquisition of learning, in the society of my fellow-students of equal age.

“And among them I had a friend, a promising young man of the military caste, Vijayasena by name, the son of a very rich Kṣatriya. And one day the unmarried sister of that friend of mine, whose name was Madirāvatī, came with him to my teacher’s house. So beautiful was she that I feel convinced that the Creator made the orb of the moon, that is like nectar to the eyes of men, out of the overflowing of the perfect loveliness of her face. I ween, the God of Love, when he beheld her form, which was to him a sixth weapon, bewildering the world, valued but little his other five shafts. When I saw her, and heard from that friend her name and descent, I was at once overpowered by love’s potent sway, and my mind was altogether fixed upon her. And she, for her part, looked askance at me with modest loving eye, and the down standing erect on her cheeks told that love had begun to sprout. And after she had remained there a long time on the pretext of play, she at last tore herself away and went home, sending to me from the reverted corner of her eye a look that was a messenger of love.

“Then I went home, grieved at having to part with her, and throwing myself flat, I tossed up and down convulsively, like a fish on dry land.

I said to myself:

‘Shall I ever again behold her face, which is the Creator’s storehouse of all the nectar of beauty? Happy are her companions[7] whom she looks at with that laughing eye, and talks freely to with that mouth.’

Engaged in such thoughts as these, I with difficulty got through that day and night, and on the second day I went to the house of my teacher.

“There my friend Vijayasena approached me courteously, and in the course of a confidential conversation said to me joyfully:

‘My mother has heard from my sister Madirāvatī that you are so great a friend of mine, and being full of love for you, she wishes to behold you. So, if you have any regard for me, come with me to our house: let it be adorned for us with the dust of your lotus-like foot.’

This speech of his was a sudden refreshment to me, as an unexpected heavy shower of rain is to a traveller in the desert. So I consented, and went to his house, and there I had an interview with his mother, and was welcomed by her, and remained there, gladdened by beholding my beloved.

“Then Vijayasena, having been summoned by his father, left me, and the foster-sister of Madirāvatī came to me, and said, bowing before me:

‘Prince, the Princess Madirāvatī trained up to maturity in our garden a jasmine creeper; and it has recently produced a splendid crop of flowers, which laugh and gleam with joyous exultation at being united with the spring. To-day the princess herself has gathered its buds, in defiance of the bees that settled on the flowers; and she has threaded them like pearls into a necklace, and she sends this to you her old friend as a new present.’

When that dexterous girl had said this, she gave me the garland, and with it leaves of the betel, together with camphor and the five fruits.[8] So I threw round my neck the garland, which my beloved had made with her own hand, and I enjoyed exceeding pleasure, surpassing the joy of many embraces.[9]

And putting the betel into my mouth, I said to that dear companion of hers:

‘What can I say more than this: I have in my heart such intense love for your companion, that if I could sacrifice my life for her I should consider that it had not been given me in vain; for she is the sovereign of my being.’

When I had said this I dismissed her, and I went to my teacher’s house with Vijayasena, who had that moment come in.

“The next day Vijayasena came with Madirāvatī to our house, to the great delight[10] of my parents. So the love of myself and Madirāvatī, though carefully concealed, increased every day from being in one another’s society.

“And one day a servant of Madirāvatī’s said to me in secret:

‘Listen, noble sir, and lay up[11] in your heart what I am going to tell you. Ever since my darling Madirāvatī beheld you there in your teacher’s house she has no appetite for her food, she does not adorn herself, she takes no pleasure in music, she does not play with her parrots and other pets; she finds that fanning with plantain leaves, and moist anointings with sandalwood ointment,[12] and the rays of the moon, though cool as snow, torture her with heat; and every day she grows perceptibly thinner, like the streak of the moon in the black fortnight, and the only thing that seems to give her any relief is conversation about you. This is what my daughter told me, who knows all that she does, who attends her like a shadow, and never leaves her side. Moreover, I drew Madirāvatī herself into a confidential conversation and questioned her, and she confessed to me that her affections were fixed on you. So now, auspicious sir, if you wish her life to be saved, take steps to have her wishes fulfilled.’

This nectarous speech of hers delighted me, and I said:

‘That altogether depends on you; I am completely at your disposal.’

When she heard this she returned delighted, and I, relying on her, conceived hopes, and went home with my mind at ease.

“The next day an influential young Kṣatriya came from Ujjayinī and asked Madirāvatī’s father for her hand. And her father promised to give him his daughter; and I heard that news, terrible to my ears, from her attendants. Then I was for a long time amazed, as if fallen from heaven, as if struck with a thunderbolt, as if possessed by a demon.

But I recovered, and said to myself:

‘What is the use of bewilderment now? I will wait and see the end. It is the self-possessed man that gains his desire.’

“Buoyed up by such hopes I passed some days, and my beloved one’s companions came to me and supported me by telling me what she said. But at last Madirāvatī was informed that the auspicious moment had been fixed, and the day of her marriage arrived, celebrated with great rejoicings. So she was shut up in her father’s house, and prevented from roaming about at will, and the processional entry of the bridegroom’s friends drew nigh, heralded by the sound of drums.

“When I saw that, I considered that my miserable life had lost all its zest, and came to the conclusion that death was to be preferred to separation. So I went outside the city and climbed up a banyan-tree, and fastened a noose to it, and I let myself drop from the tree suspended by that noose, and let go at the same time my chimerical hope of obtaining my beloved. And a moment afterwards I found myself, having recovered the consciousness which I had lost, lying in the lap of a young man who had cut the noose.

And perceiving that he had without doubt saved my life, I said to him:

‘Noble sir, you have to-day shown your compassionate nature; but I am tortured by separation from my beloved and I prefer death to life. The moon is like fire to me, food is poison, songs pierce my ear like needles, a garden is a prison, a wreath of flowers is a series of envenomed shafts, and anointing with sandalwood ointment and other unguents[13] is a rain of burning coals. Tell me, friend, what pleasure can wretched bereaved ones, like myself, to whom everything in the world is turned upside down, find in life?’

“When I had said this, that friend in misfortune asked me my history, and I told him the whole of my love affair with Madirāvatī. Then that good man said to me:

‘Why, though wise, are you bewildered? What is the use of surrendering life, for the sake of which we acquire all other things? À propos of this, hear my story, which I now proceed to relate to you.

“‘There is in the bosom of the Himālayas a country named Niṣadha, which is the only refuge of virtue, banished from the earth by Kali, and the native land of truth, and the home of the Kṛta age. The inhabitants of that land are insatiable of learning, but not of money-getting; they are satisfied with their own wives, but with benefiting others never. I am the son of a Brāhman of that country who was rich in virtue and wealth. I left my home, my friend, out of a curiosity which impelled me to see other countries, and wandering about, visiting teachers, I reached in course of time the city of Śaṅkhapura not far from here, where there is a great purifying lake of clear water, sacred to Śaṅkhapāla, King of the Nāgas, and called Śaṅkhahrada.

“‘While I was living there in the house of my spiritual preceptor I went one holy bathing festival to visit the lake Śaṅkhahrada. Its banks were crowded, and its waters troubled on every side by people who had come from all countries, like the sea when the gods and Asuras churned it. I beheld that great lake, which seemed to make the women look more lovely as their garlands of flowers fell from their loosened braids, while it gently stroked their waists with its waves like hands, and made itself slightly yellow[14] with the unguents which its embraces rubbed off from their bodies. I then went to the south of the lake, and beheld a clump of trees, which looked like the body of Kāma being consumed by the fire of Śiva’s eye; its tāpinchas[15] did duty for smoke, its kiṃśukas[16] for red coals, and it was all aflame with twining masses of the full-blown scarlet aśoka.[17]

“‘There I saw a certain maiden gathering flowers at the entrance of an arbour composed of the atimukta creeper.[18] She seemed, with her playful sidelong glances, to be threatening the lotus in her ear; she kept raising her twining arm and displaying half her bosom, and her beautiful loosened hair, hanging down her back, seemed like the darkness seeking shelter to escape from her moon-like face.

And I said to myself:

“Surely the Creator must have made this girl, after he had got his hand in by creating Rambhā and her sister-nymphs, but one can see that she is mortal by the winking of her eyes.”[19]

“‘The moment I saw that gazelle-eyed maid, she pierced my heart, like a crescent-headed javelin of Māra, bewildering the three worlds. And the moment she saw me she was overcome by Kāma, and her hands were rendered nerveless and listless by love, and she desisted from her amusement of gathering flowers. She seemed, with the flashings of the ruby in the midst of her moving flexible chain,[20] to be displaying the flames of affection, that had broken forth from her heart, in which they could not be contained; and turning round, she looked at me again and again with an eye that seemed to be rendered more charming by the pupil coming down to rest in its corner.

“‘While we stood for a time looking at one another, there arose there a great noise of people flying in terror. And there came that way an infuriated elephant, driven mad by the smell of wild elephants; it had broken its chain and thrown its rider, and the elephant-hook was swinging to and fro at the end of its ear. The moment I saw the animal I rushed forward, and taking up in my arms my beloved, who was terrified, and whose attendants had run away, I carried her into the middle of the crowd. Then she began to recover her composure, and her attendants came up; but just at that moment the elephant, attracted by the noise of the people, charged in our direction. The crowd dispersed in terror at the monster’s approach, and she disappeared among them, having been carried off by her attendants in one direction, while I went in another.

“‘At last the alarm caused by the elephant came to an end, and then I searched in every direction for that slender-waisted maid, but I could not find her, as I did not know her name, her family or her dwelling-place; and so roaming about, with a void in my heart, like a Vidyādhara that has lost his magic power, I with difficulty tottered in to my teacher’s house. There I remained like one in a faint or asleep, remembering the joy of embracing my beloved, and anxious lest her love might fail.[21] And in course of time reflection lulled me in her lap, as if affected with the compassion natural to noble women, and showed me a glimpse of hope, and soul-paining ignorance hugged my heart, and an exceedingly severe headache took possession of my brain.[22] In the meanwhile the day slipped away, and my self-command with it, and the lotus-thicket folded its cups and my face was contracted with them, and the couples of Brahmany ducks were dispersed[23] with my hopes, the sun having gone to rest.

“‘Then the moon, the chief friend of love, that gladdens the eyes of the happy, rose up, adorning the face of the east; its rays, though ambrosial, seemed to me like fiery fingers, and though it lit up the quarters of the sky, it darkened in me all hope of life.

Then one of my fellow-students, seeing that in my misery I had flung my body into moonlight as into a fire, and was longing for death, said to me:

“Why are you in this evil case? You do not appear to have any disease; but if you have mental affliction caused by longing for wealth or by love, I will tell you the truth about those objects. Listen to me. The wealth, which through over-covetousness men desire to gain by cheating their neighbours, or by robbing them, does not remain. The poison-trees[24] of wealth, which are rooted in wickedness and bring forth an abundant crop of wickedness, are soon broken by the weight of their own fruit. All that is gained by that wealth in this world is the toil of acquiring it and other annoyances, and in the next world great suffering in hell—a suffering that shall continue as long as the moon and stars endure. As for love, that love which fails of attaining its object brings disappointment that puts an end to life, and unlawful love, though pleasing in the mouth, is simply the forerunner of the fire of hell.[25] But a man’s mind is sound owing to good actions in a former life, and a hero, who possesses self-command and energy, obtains wealth and the object of his desires, not a spiritless coward like you. So, my good fellow, have recourse to self-command, and strive for the attainment of your ends.”

“‘When that friend said this to me I returned him a careless and random answer. However, I concealed my real thoughts, spent the night in a calm and composed manner, and in course of time came here, to see if by any chance she lived in this town. When I arrived here, I saw you with your neck in a noose, and after you were cut down I heard from you your sorrow, and I have now told you my own.

“‘So I have made efforts to obtain that fair one whose name and dwelling-place I know not, and have thus exerted myself to gain what no heroism could procure; but why do you, when Madirāvatī is within your grasp, play the faintheart, instead of manfully striving to win her? Have you not heard the legend of old days with regard to Rukmiṇī? Was she not carried off by Viṣṇu after she had been given to the King of Cedi?’

“While that friend of mine was thus concluding his tale, Madirāvatī came there with her followers, preceded by the usual auspicious band of music, in order to worship the God of Love in this temple of the Mothers.

And I said to my friend:

‘I knew all along that maidens on the day of their marriage come here to worship the God of Love: this is why I tried to hang myself on the banyan-tree in front of this temple, in order that when Madirāvatī came here she might see that I had died for her sake.’

When that resolute Brāhman friend heard that, he said:

‘Then let us quickly slip into this temple and remain hidden behind the images of the Mothers, and see whether any expedient will then present itself to us or not.’

When my friend made this proposal, I consented, and went with him into that temple, and remained there concealed.

“And Madirāvatī came there slowly, escorted by the auspicious wedding music, and entered that temple. And she left at the door all her female friends and male attendants, saying to them:

‘I wish in private to crave from the awful God of Love a certain boon[26] that is in my mind, so remain all of you outside the building.’

Then she came in and addressed the following prayer to Kāmadeva after she had worshipped him:

‘O god, since thou art named “the mind-born,” how was it that thou didst not discern the beloved that was in my mind? Why hast thou disappointed and slain me? If thou hast not been able to grant me my boon in this birth, at any rate have mercy upon me in my next birth, O husband of Rati! Show me so much favour as to ensure that handsome young Brāhman’s being my husband in my next birth.’

“When the girl had said this in our hearing and before our eyes, she made a noose, by fastening her upper garment to a peg, and put it round her neck. And my friend said to me:

‘Go and show yourself to her, and take the noose from her neck.’

So I immediately went towards her. And I said to her with a voice faltering from excess of joy:

‘Do not act rashly, my beloved. See, here is your slave in front of you, bought by you with the risk of your life, in whom affection has been produced by your utterance in the moment of your grief.’

And with these words I removed the noose from the neck of that fair one.

“She immediately looked at me, and remained for a moment divided between joy and terror, and then my friend said quickly to me:

‘As this is a dimly lighted hour owing to the waning of the day, I will go out dressed in Madirāvatī’s garments with her attendants. And do you go out by the second door, taking with you this bride wrapped up in our upper garments. And make for whatever foreign country you please, during the night, when you will be able to avoid detection. And do not be anxious about me. Fate will bestow on me prosperity.’

When my friend had said this, he put on Madirāvatī’s dress and went out, and left that temple in the darkness, surrounded by her attendants.

“And I slipped out by another door with Madirāvatī, who wore a necklace of priceless jewels, and went three yojanas in the night. In the morning I took food, and slowly travelling on, I reached in the course of some days, with my beloved, a city named Acalapura. There a certain Brāhman showed himself my friend, and gave me a house, and there I quickly married Madirāvatī.

“So I have been living there in happiness, having obtained my desire, and my only anxiety has been as to what could have become of my friend. And in course of time I came here to bathe in the Ganges, on this day which is the festival of the winter solstice,[27] and lo! I found here this man who without cause showed himself my friend. And full of embarrassment I folded him in a long embrace, and at last made him sit down and asked him to tell me his adventures, and at that moment your Highness came up. Know, son of the King of Vatsa, that this other Brāhman at my side is my true friend in calamity, to whom I owe my life and my wife.”

When one Brāhman had told his story in these words, Naravāhanadatta said to the other Brāhman:

“I am much pleased: now tell me, how did you escape from so great a danger? For men like yourself, who disregard their lives for the sake of their friends, are hard to find.”

When the second Brāhman heard this speech of the son of the King of Vatsa, he also began to tell his adventures.

“When I went out that night from the temple in Madirāvatī’s dress, her attendants surrounded me under the impression that I was their mistress. And being bewildered with dancing, singing and intoxication, they put me in a palankeen[28] and took me to the house of Somadatta, which was in festal array. In one part it was full of splendid raiment, in another of piled-up ornaments; here you might see cooked food provided, there an altar-platform made ready; one corner was full of singing female slaves, another of professional mimes, and a third was occupied by Brāhmans waiting for the auspicious moment.

“Into one room of this house I was ushered in the darkness, veiled, by the servants, who were beside themselves with drink and took me for the bride. And when I sat down there, the female slaves surrounded me, full of joy at the wedding festival, busied with a thousand affairs.

“Immediately the sound of bracelets and anklets was heard near the door, and a maiden entered the room surrounded by her attendants. Like a female snake, her head was adorned with flashing jewels, and she had a white skinlike bodice; like a wave of the sea, she was full of beauty,[29] and covered with strings of pearls. She had a garland of beautiful flowers, arms shapely as the stalk of the creeper, and bright budlike fingers; and so she looked like the goddess of the garden moving among men. And she came and sat down by my side, thinking I was her beloved confidante. When I looked at her I perceived that that thief of my heart had come to me, the maiden that I saw at the Śaṅkhahrada lake, whither she had come to bathe, whom I saved from the elephant, and who, almost as soon as seen, disappeared from my sight among the crowd. I was overpowered with excess of joy, and I said to myself:

‘Can this be mere chance, or is it a dream, or sober waking reality?’

“Immediately those attendants of Madirāvatī said to the visitor:

‘Why do you seem so disturbed in mind, noble lady?’

When she heard that, she said, concealing her real feelings[30]:

‘What! Are you not aware what a dear friend of mine Madirāvatī is? And she, as soon as she is married, will go off to her father-in-law’s house, and I shall not be able to live without her; this is why I am afflicted. So leave the room quickly, in order that I may have the pleasure of a little confidential chat with Madirāvatī.’

“With these words she put them all out, and fastened the door herself, and then sat down, and, under the impression that I was her confidante, began to speak to me as follows:

‘Madirāvatī, no affliction can be greater than this affliction of yours, in that you are in love with one man and you are given by your father in marriage to another; still, you may possibly have a meeting or be united with your beloved, whom you know by having been in his society. But for me a hopeless affliction has arisen, and I will tell you what it is; for you are the only repository of my secrets, as I am of yours.

“‘I had gone to bathe on a festival in the lake named the lake of Śaṅkhahrada,[31] in order to divert my mind, which was oppressed with the approaching separation from you. While thus engaged, I saw in the garden near that lake a beautiful blooming young Brāhman, whose budding beard seemed like a swarm of bees come to feed on the lotus of his face; he himself looked like the moon come down from heaven in the day, like the golden binding-post of the elephant of beauty.

I said to myself:

“Those hermits’ daughters who have not seen this youth have only endured to no purpose hardship in the woods; what fruit have they of their asceticism?”

And even as I thought this in my heart, the God of Love pierced it so completely with his shafts that shame and fear at once left it together.

“‘Then, while I looked with sidelong looks at him whose eyes were fixed on me, there suddenly came that way a furious elephant that had escaped from its binding-post. That scared away my attendants and terrified myself; and the young man, perceiving this, ran, and taking me up in his arms, carried me a long way into the midst of the crowd. While in his arms, I assure you, my friend, I was rendered dead to all beside by the joy of his ambrosial touch, and I knew not the elephant, nor fear, nor who I was, nor where I was. In the meanwhile my attendants came up, and thereupon the elephant rushed down on us like Separation incarnate in bodily form, and my servants, alarmed at it, took me up and carried me home; and in the mêlêe my beloved disappeared, whither I know not. Ever since that time I do nothing but think on him who saved my life, but whose name and dwelling I know not, who was snatched from me as one might snatch away from my grasp a treasure that I had found; and I weep all night with the female cakravākas, longing for sleep, that takes away all grief, in order that I may behold him in a dream.

“‘In this hopeless affliction my only consolation, my friend, is the sight of yourself, and that is now being far removed from me. Accordingly, Madirāvatī, the hour of my death draws nigh, and that is why I am now enjoying the pleasure of beholding your face.’

“When she had uttered this speech, which was like a shower of nectar in my ears, staining all the while the moon of her face with tear-drops mixed with the black pigment of her eyes, she lifted up the veil from my face, and beheld and recognised me, and then she was filled with joy, wonder and fear.

Then I said:

‘Fair one, what is your cause of alarm? Here I am at your service. For Fate, when propitious, brings about unexpected results. I, too, have endured for your sake intolerable sorrow: the fact is, Fate produces a strange variety of effects in this phenomenal universe.[32] Hereafter I will tell you my story at full length; this is not the time for conversation. Now devise, if you can, my beloved, some artifice for escaping from this place.’

When I said this to the girl, she made the following proposal, which was just what the occasion demanded:

‘Let us slip out quietly from this house by the back door; the garden belonging to the house of my father, a noble Kṣatriya, is just outside: let us pass through it and go where chance may take us.’

When she had said this, she hid her ornaments, and I left the house with her by the way which she recommended.

“So in that night I went a long distance with her, for we feared detection, and in the morning we reached together a great forest. And as we were going along through that savage wilderness, with no comfort but our mutual conversation, noon gradually came on. The sun, like a wicked king, afflicted with his rays the earth, that furnished no asylum for travellers, and no shelter.[33] By that time my beloved was exhausted with fatigue and tortured with thirst, so I slowly carried her into the shade of a tree, which it cost me a great effort to reach.

“There I tried to restore her by fanning her with my garment, and while I was thus engaged, a buffalo, that had escaped with a wound, came towards us. And there followed in eager pursuit of it a man on horseback armed with a bow, whose very appearance proclaimed him to be a noble-minded hero. He slew that great buffalo with a second wound from a crescent-headed arrow, striking him down as Indra strikes down a mountain with the dint of a thunderbolt. When he saw us he advanced towards us, and said kindly to me:

‘Who are you, my good sir; and who is this lady; and why have you come here?’

“Then I showed my Brāhmanical thread, and gave him an answer which was half truth and half falsehood:

‘I am a Brāhman; this is my wife. Business led us to a foreign land, and on the way our caravan was destroyed by bandits, and we, separated from it, lost our way, and so came to enter this forest; here we have met you, and all our fears are at an end.’

When I said this, he was moved by compassion for my Brāhmanical character, and said:

‘I am a chief of the foresters come here to hunt, and you wayworn travellers have arrived here as my guests; so now come to my house, which is at no great distance, to rest.’

“When he had said this, he made my wearied darling get up on his horse, and himself walked, and so he led us to his dwelling. There he provided us with food and other requisites, as if he had been a relation.[34] Even in bad districts some few noble-hearted men spring up here and there. Then he gave me attendants, who enabled me to get out of that wood, and I reached a royal grant to Brāhmans, where I married that lady. Then I wandered about from country to country, and meeting with a caravan I have to-day come here with her to bathe in the water of the Ganges. And here I have found this man whom I selected for myself as a friend, and I have seen your Highness. This, Prince, is my story.”

When he had said this he ceased, and the Prince of Vatsa loudly praised that Brāhman who had obtained the prize he desired, the fitting reward of his genuine goodness; and in the meanwhile the prince’s ministers, Gomukha and the others, who had long been roaming about looking for him, came up and found him. And they fell at the feet of Naravāhanadatta, and tears of joy poured down their faces, while he welcomed them all with due and fitting respect. Then the prince, accompanied by Lalitalocanā,[35] returned with those ministers to his city, taking with him those two young Brāhmans, whom he valued on account of the tact and skill they had displayed in attaining worthy objects.

[Additional note 1: The use of turmeric (kuṅkuma) in ancient India]

[Additional note 2: The festival of the Winter Solstice]

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

There is, of course, an allusion to the Mānasa lake.

[2]:

See Vol. VII, p. 195.—n.m.p.

[3]:

Here there is a pun; the word translated “bees” can also mean “arrows.”

[4]:

The God of Love, the Buddhist devil.——See Vol. VI, p.187n1, and Monier Williams, Buddhism, p. 208.—n.m.p.

[5]:

The word rati in Sanskrit means “joy,” and “sexual intercourse.”

[6]:

See Vol. VII, pp. 26-28.—n.m.p.

[7]:

No. 1882 has dhanyā sa cha naro, No. 2166 dhanyaḥ sa cha naro—i.e. “happy is that man.”

[8]:

See Appendix II, p. 246 et seq. —n.m.p.

[9]:

Two of the India Office MSS. read āliṅganadhikaṃ.

[10]:

I read sammadaḥ for sampadaḥ. I find it in MSS. Nos. 1882 and 2166.

[11]:

MSS. Nos. 1882 and 2166 give cha tat for tathā.

[12]:

See Vol. VII, pp. 105-107.—n.m.p.

[13]:

See Vol. IV, p.240n1 —n.m.p.

[14]:

For the uses of turmeric see Note 1 at the end of this chapter. —N.M.P.

[15]:

I.e. Garcinia xanthochymus (Hooker, Flora of British India, vol. i, p. 269). See also Watt, Economic Products, vol. iii, pp. 478, 479.—n.m.p.

[16]:

Butea frondosa, found throughout India and Burma. It is one of the most beautiful trees of the plains. Its economic uses are manifold—gum, lac, dye, tan, pigment, oil, etc. The tree is sacred to Soma, and is used in many religious ceremonies, particularly in the investiture of the sacred thread, when the leaves are used as platters, and the stem for the sacred staff. See Watt, op. cit., vol. i, p. 548 et seq. —n.m.p.

[17]:

Jonesia asoca. This has been described by Roxburgh as perhaps one of the most beautiful trees, when in full bloom, in the whole vegetable kingdom. Its flowers are red and orange, while its leaves are abruptly pinnate and shining. In the Mṛcchakalika we have a description of a garden where “the aśoka, with its rich red blossom, shines like a young warrior bathed in the sanguine shower of the furious fight.” The tree has been regarded as a symbol of love from the time when Sītā took refuge from Rāvaṇa in a grove of aśoka trees. Kāma himself took refuge in one, when he was burnt, together with the tree, by Śiva. The flowers, owing to their auspicious colour and delicate perfume, are used largely for temple decoration. See further W. Dymock, “Flowers of the Hindu Poets,” Journ. Anth. Soc. Bomb., vol. ii, p. 87.—N.M.P.

[18]:

This is the Gaertnera racemosa, usually known in Sanskrit as Mādhavī. See Hooker, op. cit., vol. i, p. 418, and Watt, op. cit., vol. iv, pp. 252, 253. —N.M.P.

[19]:

Cf. the Nala episode in Vol. IV, p. 239.—n.m.p.

[20]:

More literally, “creeper-like chain.”

[21]:

I have followed Brockhaus’ text, which is supported,by MS. No. 3003. The other two read tatpremabhayasotkampam.

[22]:

The words denoting “reflection,” “headache” and “ignorance” are feminine in Sanskrit, and so the things denoted by them have feminine qualities attributed to them. Ignorance means perhaps “the having no news of the beloved.” All the India Office MSS. read vṛddhayā for vṛttayā.

[23]:

See Vol. VI, p.71n3.—n.m.p.

[24]:

Here the reading of MS. No. 1 882 is Pāpamūlā yataḥ pāpaphalabhāram prasūyate Tatkṣaṇenaiva bhajyante śīghraṃ dhanaviṣadrumāh. No. 3003 reads prāptamulā, tadbhareṇaiva and bhujyante. No. 2166 agrees with No. 1882 in the main, but substitutes tana for dhana. I have followed No. 1882, adopting tadbhareṇaiva from No. 3003.

[25]:

I read yaś chādharmyo’ gradūtaḥ. MS. No. 1882 reads yaś chādhamyo, No. 3003 reads yaś chādhanno, and No. 2166 reads as I propose.

[26]:

The word may mean “bridegroom.”

[27]:

Following the mistaken interpretation in the Sanskrit dictionaries Tawney translated “summer solstice.” See Note 2 at the end of this chapter.—n.m.p.

[28]:

I adopt Dr Kern’s conjecture, āropya sibikām. It is found in two out of three India Office MSS., for the loan of which I am indebted to Dr Rost. -For a note on palankeens see Vol. III, p.14n1.—n.m.p.

[29]:

The word which means “bodice” means also “the skin of a snake,” and the word translated “beauty” means also “saltness.”

[30]:

Because she really wanted to talk to Madirāvatī about her own love affair.

[31]:

I omit cha after vinodayitum, as it is not found in the three India Office MSS.

[32]:

The D. text reads yādṛśaṃ as the first word of the line instead of tādṛśi. This must be construed with the preceding line, and the sense would necessarily be altered as follows: “Hereafter I will tell you of what kind was the intolerable sorrow I, too, have endured for your sake, and how strange a variety of effects in this phenomenal world Fate produces.” See Speyer, op. cit., pp. 141, 142.—n.m.p.

[33]:

The whole passage is an elaborate pun resting upon the fact that the same word means “tribute” and “ray” in Sanskrit. Ākranda sometimes means “protector.”

[34]:

I read bāndhavavat so. The late Professor Horace Hayman Wilson observes of this story:

“The incidents are curious and diverting, but they are chiefly remarkable from being the same as the contrivances by which Mādhava and Makaraṇḍa obtain their mistresses in the drama entitled Mālañ and Mādhava or The Stolen Marriage.”

——For the plot of Bhavabhūti’s Mālatīmādhava (circa a.d. 700) see Keith, Sanskrit Drama, pp. 187, 188, and also pp. 192, 193. —N.M.P.

[35]:

See Vol. VII, p. 195.—n.m.p.