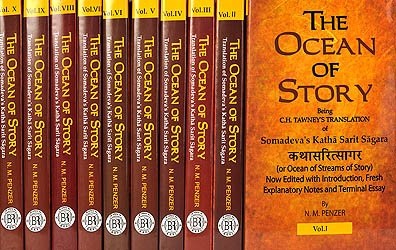

Kathasaritsagara (the Ocean of Story)

by Somadeva | 1924 | 1,023,469 words | ISBN-13: 9789350501351

This is the English translation of the Kathasaritsagara written by Somadeva around 1070. The principle story line revolves around prince Naravāhanadatta and his quest to become the emperor of the Vidhyādharas (‘celestial beings’). The work is one of the adoptations of the now lost Bṛhatkathā, a great Indian epic tale said to have been composed by ...

Chapter XCII

163g. King Trivikramasena and the Mendicant

THEN in that cemetery, full of flames of funeral pyres, as of demons, flesh-devouring, with lolling tongues of fire, the undaunted King Trivikramasena went back that same night to the śiṃśapā tree.

And there he unexpectedly saw many corpses of similar appearance hanging upon the tree, and they all seemed to be possessed by Vetālas. The king said to himself:

“Ah! what is the meaning of this? Is this deluding Vetāla doing this now in order to waste time? For I do not know which of these many corpses here I ought to take. If this night shall pass away without my accomplishing my object I will enter the fire, I will not put up with disgrace.”

But the Vetāla discovered the king’s intention, and pleased with his courage he withdrew that delusion. Then the king beheld only one Vetāla on the tree in the corpse of a man, and he took it down, and put it on his shoulder, and once more started off with it. And as he trudged along, the Vetāla again said to him:

“King, your fortitude is wonderful; so listen to this my tale.

163g (18). The Brahman’s Son who failed to acquire the Magic Power[1]

There is a city called Ujjayinī, inferior only to Bhogavatī and Amarāvatī, which Śiva, who was won by the toilsome asceticism of Gaurī, being in love with the matchless preeminence of its excellence, himself selected as his habitation. It is full of various enjoyments, to be attained only by distinguished well-doing; in that city stiffness and hardness is seen only in the bosoms of the ladies,[2] curvature only in their eyebrows,[3] and fickleness only in their rolling eyes; darkness only in the nights; crookedness only in the ambiguous phrases of poets; madness only in elephants; and coldness only in perils, sandalwood juice and the moon.

In that city there was a learned Brāhman, named Devasvāmin, who had offered many sacrifices, and possessed great wealth, and who was highly honoured by the king, whose name was Candraprabha. In time there was born to that Brāhman a son, named Candrasvāmin, and he, though he had studied the sciences, was, when he grew up, exclusively devoted to the vice of gambling.[4] Now once on a time that Brāhman’s son, Candrasvāmin, entered a great gambling-hall to gamble.

Calamities seemed to be continually watching that hall with tumbling dice for rolling eyes, like the black antelope in colour, and saying to themselves:

“Whom shall we seize on here?”

And the hall, full of the noise of the altercations of gamblers, seemed to utter this cry:

“Who is there whose wealth I could not take away? I could impoverish even Kuvera, the lord of Alakā.”

Then he entered the hall, and playing dice with gamblers, he lost his clothes and all, and then he lost borrowed money in addition. And when he was called upon to pay that impossible sum, he could not do it, so the keeper of the gambling-hall seized him and beat him with sticks.[5] And that Brāhman’s son, when beaten with sticks all over his body, made himself motionless as a stone, and to all appearance dead, and remained in that state.

When he had remained there in that condition for two or three days, the proprietor of the gambling establishment got angry, and said, in the gambling-hall, to the gamblers who frequented it:

“This fellow has begun to try on the petrifaction dodge, so take the spiritless wretch and throw him into some blind well; but I will give you the money.”

When the proprietor said this to the gamblers they took up Candrasvāmin, and carried him to a distant wood, to look for a well. There an old gambler said to the others:

“This fellow is all but dead; so what is the good of throwing him into a well now? So let us leave him here, and say that we left him in a well.”

All approved his speech, and agreed to do as he recommended.

Then the gamblers left Candrasvāmin there and went their ways, and he rose up and entered an empty temple of Śiva that stood near. There he recovered his strength a little, and reflected in his grief:

“Alas! being over-confiding, I have been robbed by these gamblers by downright cheating, so where can I go in this condition, naked, cudgelled and begrimed with dust? What would my father, my relations or my friends say of me, if they saw me? So I will remain here for the present, and at night I will go out, and see how I can make shift to get food, to satisfy my hunger.”

While he was going through these reflections, in hunger and nakedness, the sun abated his heat, and abandoned his garment the sky, and went to the mountain of setting.

Thereupon there came there a Pāśupata ascetic, with his body smeared with ashes, with matted hair and a trident, looking like a second Śiva.

When he saw Candrasvāmin he said to him: “Who are you?”

Thereupon Candrasvāmin told him his story, and bowed before him, and the hermit, when he heard it, said to him:

“You have arrived at my hermitage, as an unexpected guest, exhausted with hunger; so rise up, bathe and take a portion of the food I have obtained by begging.”

When the hermit said this to Candrasvāmin he answered:

“Reverend sir, I am a Brāhman; how can I eat a part of your alms?”

When the hospitable hermit, who possessed magic powers, heard that, he entered his hut, and called to mind the science which produced whatever one desires, and the science appeared to him when he called it to mind, and said: “What shall I do for you?”

And he gave it this order: “Provide entertainment for this guest.”

The science answered: “I will.”

And then Candrasvāmin beheld a golden city rise up, with a garden attached to it, and full of female attendants.

And those females came out of that city, and approached the astonished Candrasvāmin, and said to him:

“Rise up, good sir; come, eat and forget your fatigue.”

Then they took him inside, and made him bathe, and anointed him; and they put splendid garments on him, and took him to another magnificent dwelling. And there the young man beheld a young woman who seemed their chief, who was beautiful in all her limbs, and appeared to have been made by the Creator out of curiosity to see what he could do. She rose up, eager to welcome him, and made him sit beside her on her throne; and he partook with her of heavenly food, and ate with much delight betel-nut, flavoured with five fruits.

And next morning he woke up, and saw only that temple of Śiva there, and neither that city, nor that heavenly lady, nor her attendants. Then the hermit came out of the hut, smiling, and asked him how he had enjoyed himself in the night, and the discreet Candrasvāmin, in his despondency, said to the hermit:

“By your favour, reverend sir, I spent the night happily enough; but now, without that heavenly lady, my life will depart.”

When the hermit heard that, being kind-hearted, he laughed and said to him:

“Remain here; you shall have exactly the same experiences this night also.”

When the hermit said this, Candrasvāmin consented to stay, and by the favour of the hermit he was provided, by the same means, with the same enjoyments every night.

And at last he understood that this was all produced by magic science, so, one day, impelled by destiny, he coaxed that mighty hermit and said to him:

“If, reverend sir, you really take pity on me, who have fled to you for protection, bestow on me that science, whose power is so great.”

When he urged this request persistently, the hermit said to him:

“You cannot attain this science; for it is attained under the water, and while the aspirant is muttering spells under the water, the science creates delusions to bewilder him, so that he does not attain success. For there he sees himself born again, and a boy, and then a youth, and then a young man, and married, and then he supposes that he has a son. And he is falsely deluded, supposing that one person is his friend and another his enemy, and he does not remember this birth, nor that he is engaged in a magic rite for acquiring science. But whoever, when he seems to have reached twenty-four years, is recalled to consciousness by the science of his instructor, and, being firm of soul, remembers his real life, and knows that all he supposes himself to experience is the effect of illusion, and though he is under the influence of it enters the fire, attains the science, and rising from the water sees the real truth. But if the science is not attained by the pupil on whom it is bestowed, it is lost to the teacher also, on account of its having been communicated to an unfit person. You can attain all the results you desire by my possession of the science; why do you show this persistence? Take care that my power is not lost, and that your enjoyment is not lost also.”

Though the hermit said this, Candrasvāmin persisted in saying to him:

“I shall be able to do all that is required[6]; do not be anxious about that.”

Then the hermit consented to give him the science. What will not good men do for the sake of those that implore their aid? Then the Pāśupata ascetic went to the bank of the river, and said to him:

“My son, when, in repeating this charm, you behold that illusion, I will recall you to consciousness by my magic power, and you must enter the fire which you will see in your illusion. For I shall remain here all the time on the bank of the river to help you.”

When that prince of ascetics had said this, being himself pure, he duly communicated that charm to Candrasvāmin, who was purified and had rinsed his mouth with water.

Then Candrasvāmin bowed low before his teacher, and plunged boldly into the river, while he remained on the bank. And while he was repeating over that charm in the water, he was at once bewildered by its deluding power, and cheated into forgetting the whole of that birth. And he imagined himself to be born in his own person in another town, as the son of a certain Brāhman, and he slowly grew up. And in his fancy he was invested with the Brāhmanical thread, and studied the prescribed sciences, and married a wife, and was absorbed in the joys and sorrows of married life, and in course of time had a son born to him, and he remained in that town engaged in various pursuits, enslaved by love for his son, devoted to his wife, with his parents and relations.

While he was thus living through in his fancy a life other than his real one, the hermit, his teacher, employed the charm whose office it was to rouse him at the proper season. He was suddenly awakened from his reverie by the employment of that charm, and recollected himself and that hermit, and became aware that all that he was apparently going through was magic illusion, and he became eager to enter the fire, in order to gain the fruit which was to be attained by the charm; but he was surrounded by his elders, friends, superiors and relations, who all tried to prevent him. Still, though they used all kinds of arguments to dissuade him, being desirous of heavenly enjoyment, he went with his relations to the bank of the river, on which a pyre was prepared.

There he saw his aged parents and his wife ready to die with grief, and his young children crying; and in his bewilderment he said to himself:

“Alas! my relations will all die if I enter the fire, and I do not know if that promise of my teacher’s is true or not. So shall I enter the fire? Or shall I not enter it? After all, how can that promise of my teacher’s be false, as it is so precisely in accordance with all that has taken place? So, I will gladly enter the fire.”

When the Brāhman Candrasvāmin had gone through these reflections, he entered the fire.

And to his astonishment the fire felt as cool to him as snow. Then he rose up from the water of the river, the delusion having come to an end, and went to the bank. There he saw his teacher on the bank, and he prostrated himself at his feet, and when his teacher questioned him, he told him all his experiences, ending with the cool feel of the fire.

Then his teacher said to him:

“My son, I am afraid you have made some mistake in this incantation, otherwise how can the fire have become cool to you? This phenomenon in the process of acquiring this science is unprecedented.”

When Candrasvāmin heard this remark of the teacher’s he answered:

“Reverend sir, I am sure that I made no mistake.”

Then the teacher, in order to know for certain, called to mind that science, and it did not present itself to him or his pupil. So, as both of them had lost the science, they left that place despondent.

163g. King Trivikramasena and the Mendicant

When the Vetāla had told this story, he once more put a question to King Trivikramasena, after mentioning the same condition as before:

“King, resolve this doubt of mine; tell me, why was the science lost to both of them, though the incantation was performed in the prescribed way?”

When the brave king heard this speech of the Vetāla’s he gave him this answer:

“I know, lord of magic, you are bent on wasting my time here; still I will answer. A man cannot obtain success, even by performing correctly a difficult ceremony, unless his mind is firm, and abides in spotless courage, unhesitating and pure from wavering. But in that business the mind of that spiritless young Brāhman wavered, even when roused by his teacher,[7] so his charm did not attain success, and his teacher lost his mastery over the charm, because he had bestowed it on an undeserving aspirant.”

When the king had said this, the mighty Vetāla again left his shoulder and went back invisible to his own place, and the king went back to fetch him as before.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

See Appendix, pp. 244-249.—n.m.p.

[2]:

See Vol. I, p. 30n2, 31n.—n.m.p.

[3]:

Bhanga also means defeat.

[4]:

This vice was prevalent even in the Vedic age. See Zimmer, Alt-Indisches Leben, pp. 283-287; Muir’s Sanskrit Texts, vol. v, pp. 425-430. It is well known that the plot of the Mahābhārata principally turns on this vice.—See Ocean, Vol. II, pp. 231n1, 232n.—n.m.p.

[5]:

Compare the conduct of Māthura in the Mṛcchakaṭika. For the penniless state of the gambler see p. 195, and Gaal, Märchen der Magyaren, p. 3.

[6]:

I read sakṣyāmi, with the Sanskrit College MS.

[7]:

Prabodhya should, I think, be prabudhya.