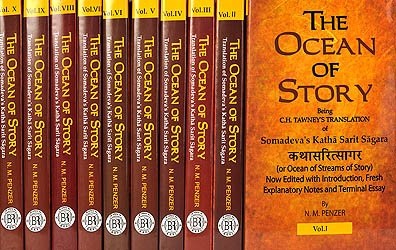

Kathasaritsagara (the Ocean of Story)

by Somadeva | 1924 | 1,023,469 words | ISBN-13: 9789350501351

This is the English translation of the Kathasaritsagara written by Somadeva around 1070. The principle story line revolves around prince Naravāhanadatta and his quest to become the emperor of the Vidhyādharas (‘celestial beings’). The work is one of the adoptations of the now lost Bṛhatkathā, a great Indian epic tale said to have been composed by ...

Chapter LXXXIV

163g. King Trivikramasena and the Mendicant

THEN Trivikramasena went and took the Vetāla from the śiṃśapā tree, and put him on his shoulder once more, and set out; and as he was going along, the Vetāla said from the top of his shoulder:

“You are weary, King, so listen to this tale that is capable of dispelling weariness.

163g (10). Madanasenā and her Rash Promise[1]

There was an excellent king of the name of Vīrabāhu, who imposed his orders on the heads of all kings. He had a splendid city named Anaṅgapura, and in it there lived a rich merchant named Arthadatta; that merchant-prince had for elder child a son named Dhanadatta, and his younger child was a pearl of maidens, named Madanasenā.

One day, as she was playing with her companions in her own garden, a young merchant, named Dharmadatta, a friend of her brother’s, saw her. When he saw that maiden, who with the full streams of her beauty, her breasts like pitchers half-revealed, and three wrinkles like waves, resembled a lake for the elephant of youth to plunge in in sport, he was at once robbed of his senses by the arrows of love, that fell upon him in showers. He thought to himself: “Alas, this maiden, illuminated with this excessive beauty, has been framed by Māra,[2] as a keen arrow to cleave asunder my heart.”

While engaged in such reflections, he watched her long; the day passed away for him as if he were a cakra-vāka.[3] Then Madanasenā entered her house, and grief at no longer beholding her entered the breast of Dharmadatta. And the sun sank red into the western main, as if inflamed with the fire of grief at seeing her no more. And the moon, that was surpassed by the lotus of her countenance, knowing that that fair-faced one had gone in for the night, slowly mounted upward.

In the meanwhile Dharmadatta went home, and thinking upon that fair one, he remained tossing to and fro on his bed, smitten by the rays of the moon.[4] And though his friends and relations eagerly questioned him, he gave them no answer, being bewildered by the demon of love. And in the course of the night he at length fell asleep, though with difficulty, and still he seemed to behold and court that loved one in a dream; to such lengths did his longing carry him. And in the morning he woke up, and went and saw her once more in that very garden, alone and in privacy, waiting for her attendant. So he went up to her, longing to embrace her, and falling at her feet he tried to coax her with words tender from affection.

But she said to him with great earnestness:

“I am a maiden betrothed to another. I cannot now be yours, for my father has bestowed me on the merchant Samudradatta, and I am to be married in a few days. So depart quietly: let not anyone see you; it might cause mischief.”

But Dharmadatta said to her:

“Happen what may, I cannot live without you!”

When the merchant’s daughter heard this, she was afraid that he would use force to her, so she said to him:

“Let my marriage first be celebrated here, let my father reap the long-desired fruit of bestowing a daughter in marriage; then I will certainly visit you, for your love has gained my heart.”

When he heard this, he said:

“I love not a woman who has been embraced by another man: does the bee delight in a lotus on which another bee has settled?”

When he said this to her, she replied:

“Then I will visit you as soon as I am married, and afterwards I will go to my husband.”

But though she made this promise, he would not let her go without further assurance, so the merchant’s daughter confirmed the truth of her promise with an oath. Then he let her go, and she entered her house in low spirits.

And when the lucky day had arrived, and the auspicious ceremony of marriage had taken place, she went to her husband’s house and spent that day in merriment, and then retired with him. But she repelled her husband’s caresses with indifference, and when he began to coax her she burst into tears.

He thought to himself, “Of a truth she cares not for me,” and said to her,

“Fair one, if you do not love me, I do not want you; go to your darling, whoever he may be.”

When she heard this, she said slowly, with downcast face: “I love you more than my life, but hear what I have to say. Rise up cheerfully, and promise me immunity from punishment; take an oath to that effect, my husband, in order that I may tell you.”

When she said this, her husband reluctantly consented, and then she went on to say with shame, despondency and fear:

“A young man of the name of Dharmadatta, a friend of my brother’s, saw me once alone in our garden, and smitten with love, he detained me; and when he was preparing to use force, I, being anxious to secure for my father the merit giving of a daughter in marriage, and to avoid all scandal, made this agreement with him:

‘When I am married, I will pay you a visit before I go to my husband’;

so I must now keep my word. Permit me, my husband. I will pay him a visit first, and then return to you, for I cannot transgress the law of truth which I have observed from my childhood.”

When Samudradatta had been thus suddenly smitten by this speech of hers, as by a down-lighting thunderbolt, being bound by the necessity of keeping his word, he reflected for a moment as follows:

“Alas! she is in love with another man; she must certainly go! Why should I make her break her word? Let her depart! Why should I be so eager to have her for a wife?”

After he had gone through this train of thought, he gave her leave to go where she would; and she rose up and left her husband’s house.

In the meanwhile the cold-rayed moon ascended the great eastern mountain, as it were the roof of a palace, and the nymph of the eastern quarter smiled, touched by his finger.

Then, though the darkness was still embracing his beloved herbs in the mountain caves, and the bees were settling on another cluster of kumudas, a certain thief saw Madanasenā as she was going along alone at night, and rushing upon her, seized her by the hem of her garment.

He said to her:

“Who are you, and where are you going?”

When he said this, she, being afraid, said:

“What does that matter to you? Let me go! I have business here.”

Then the thief said:

“How can I, who am a thief, let you go?”

Hearing that, she replied:

“Take my ornaments.”

The thief answered her:

“What do I care for these gems, fair one? I will not surrender you, the ornament of the world, with your face like the moonstone, your hair black like jet, your waist like a diamond,[5] your limbs like gold, fascinating beholders with your ruby-coloured feet.”

When the thief said this, the helpless merchant’s daughter told him her story, and entreated him as follows:

“Excuse me for a moment, that I may keep my word, and as soon as I have done that, I will quickly return to you, if you remain here. Believe me, my good man, I will never break this true promise of mine.”

When the thief heard that, he let her go, believing that she was a woman who would keep her word, and he remained in that very spot, waiting for her return.

She, for her part, went to that merchant Dharmadatta. And when he saw that she had come to that wood, he asked her how it happened, and then, though he had longed for her, he said to her, after reflecting a moment:

“I am delighted at your faithfulness to your promise; what have I to do with you, the wife of another? So go back, as you came, before anyone sees you.”

When he thus let her go, she said,

“So be it,”

and leaving that place, she went to the thief, who was waiting for her in the road. He said to her:

“Tell me what befell you when you arrived at the trysting-place.”

So she told him how the merchant let her go. Then the thief said:

“Since this is so, then I also will let you go, being pleased with your truthfulness: return home with your ornaments!”

So he too let her go, and went with her to guard her. And she returned to the house of her husband, delighted at having preserved her honour. There the chaste woman entered secretly, and went delighted to her husband. And he, when he saw her, questioned her; so she told him the whole story. And Samudradatta, perceiving that his good wife had kept her word without losing her honour, assumed a bright and cheerful expression, and welcomed her as a pure-minded woman, who had not disgraced her family, and lived happily with her ever afterwards.

163g. King Trivikramasena and the Mendicant

When the Vetāla had told this story in the cemetery to King Trivikramasena, he went on to say to him:

“So tell me, King, which was the really generous man of those three, the two merchants and the thief? And if you know and do not tell, your head shall split into a hundred pieces.”

When the Vetāla said this, the king broke silence, and said to him:

“Of those three the thief was the only really generous man, and not either of the two merchants. For of course her husband let her go, though she was so lovely and he had married her: how could a gentleman desire to keep a wife that was attached to another? And the other resigned her because his passion was dulled by time, and he was afraid that her husband, knowing the facts, would tell the king the next day. But the thief, a reckless evildoer, working in the dark, was really generous, to let go a lovely woman, ornaments and all.”

When the Vetāla heard that, he left the shoulder of the king and returned to his own place, as before; and the king, with his great perseverance no whit dashed, again set out, as before, to bring him.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

See Appendix, pp. 199-204.—n.m.p.

[2]:

See Vol. VI, p. 187nl.—n.m.p.

[3]:

See Vol. VI, p. 7ln3. For a note on the name “Brāhmani” see Crooke, Ind. Ant., vol. x, 1881, p. 293, and also his new edition of Religion and Folk-Lore of Northern India, p. 374.—n.m.p.

[4]:

See Vol. VI, pp. 100n1, 101n.—n.m.p.

[5]:

The word vajra also means thunderbolt.