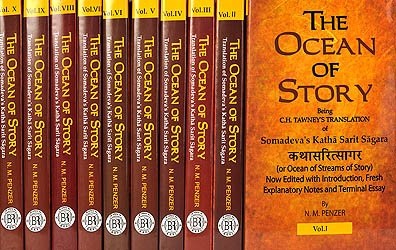

Kathasaritsagara (the Ocean of Story)

by Somadeva | 1924 | 1,023,469 words | ISBN-13: 9789350501351

This is the English translation of the Kathasaritsagara written by Somadeva around 1070. The principle story line revolves around prince Naravāhanadatta and his quest to become the emperor of the Vidhyādharas (‘celestial beings’). The work is one of the adoptations of the now lost Bṛhatkathā, a great Indian epic tale said to have been composed by ...

Chapter LXXXII

163g. King Trivikramasena and the Mendicant

THEN King Trivikramasena returned to the śiṃśapā tree and again caught the Vetāla, and put him on his shoulder, and set out with him. And as he was going along, the Vetāla again said to him from his shoulder:

“King, in order that you may forget your toil, listen to this question of mine.

163g (8). The Three Fastidious Men [1]

There is a great tract of land assigned to Brāhmans in the country of Aṅga, called Vṛkṣaghaṭa. In it there lived a rich sacrificing Brāhman named Viṣṇusvāmin. And he had a wife equal to himself in birth. And by her he had three sons born to him, who were distinguished for preternatural acuteness. In course of time they grew up to be young men. One day, when he had begun a sacrifice, he sent those three brothers to the sea to fetch a turtle.

So off they went, and when they had found a turtle, the eldest said to his two brothers:

“Let one of you take the turtle for our father’s sacrifice; I cannot take it, as it is all slippery with slime.”

When the eldest brother said this, the two younger ones answered him:

“If you hesitate about taking it, why should not we?”

When the eldest heard that, he said:

“You two must take the turtle; if you do not, you will have obstructed our father’s sacrifice, and then you and he will certainly sink down to hell.”

When he told the younger ones this they laughed, and said to him:

“If you see our duty so clearly, why do you not see that your own is the same?”

Then the eldest said:

“What! do you not know how fastidious I am? I am very fastidious about eating, and I cannot be expected to touch what is repulsive.”

The middle brother, when he heard this speech of his, said to his brother:

“Then I am a more fastidious person than you, for I am a most fastidious connoisseur of the fair sex.”

When the middle one said this, the eldest went on to say:

“Then let the younger of you two take the turtle!”

Then the youngest brother frowned, and in his turn said to the two elder:

“You fools! I am very fastidious about beds, so I am the most fastidious of the lot.”

So the three brothers fell to quarrelling with one another, and being completely under the domination of conceit, they left that turtle and went off immediately to the court of the king of that country, whose name was Prasenajit, and who lived in a city named Viṭaṅkapura, in order to have the dispute decided. There they had themselves announced by the warder, and went in, and gave the king a circumstantial account of their case.

The king said: “Wait here, and I will put you all in turn to the proof”; so they agreed and remained there.

And at the time that the king took his meal, he had them conducted to a seat of honour and given delicious food fit for a king, possessing all the six flavours.[2] And while all were feasting around him, the Brāhman who was fastidious about eating, alone of all the company, did not eat, but sat there with his face puckered up with disgust.

The king himself asked the Brāhman why he did not eat his food, though it was sweet and fragrant, and he slowly answered him:

“I perceive in this cooked rice an evil smell of the reek from corpses, so I cannot bring myself to eat it, however delicious it may be.”

When he said this before the assembled multitude, they all smelled it by the king’s orders, and said:

“This food is prepared from white rice, and is good and fragrant.”

But the Brāhman who was so fastidious about eating would not touch it, but stopped his nose. Then the king reflected, and proceeded to inquire into the matter, and found out from his officers[3] that the food had been made from rice which had been grown in a field near the burning-ghāt of a certain village.

Then the king was much astonished and, being pleased, he said to him:

“In truth you are very particular as to what you eat, so eat of some other dish.”

And after they had finished their dinner, the king dismissed the Brāhmans to their apartments and sent for the loveliest lady of his court. And in the evening he sent that fair one, all whose limbs were of faultless beauty, splendidly adorned, to the second Brāhman, who was so squeamish about the fair sex. And that matchless kindler of Kama’s flame, with a face like the full moon of midnight, went, escorted by the king’s servants, to the chamber of the Brāhman.

But when she entered, lighting up the chamber with her brightness, that gentleman who was so fastidious about the fair sex felt quite faint, and stopping his nose with his left hand, said to the king’s servants:

“Take her away: if you do not, I am a dead man; a smell comes from her like that of a goat.”

When the king’s servants heard this, they took the bewildered fair one to their sovereign, and told him what had taken place.

And the king immediately had the squeamish gentleman sent for, and said to him:

“How can this lovely woman, who has perfumed herself with sandalwood, camphor, black aloes, and other splendid scents, so that she diffuses exquisite fragrance through the whole world, smell like a goat?”

But though the king used this argument with the squeamish gentleman, he stuck to his point. And then the king began to have his doubts on the subject, and at last, by artfully framed questions, he elicited from the lady herself that, having been separated in her childhood from her mother and nurse, she had been brought up on goat’s milk.

Then the king was much astonished, and praised highly the discernment of the man who was fastidious about the fair sex, and immediately had given to the third Brāhman who was fastidious about beds, in accordance with his taste, a bed composed of seven mattresses placed upon a bedstead. White smooth sheets and coverlets were laid upon the bed, and the fastidious man slept on it in a splendid room. But before half a watch of the night had passed he rose up from that bed, with his hand pressed to his side, screaming in an agony of pain. And the king’s officers, who were there, saw a red crooked mark on his side, as if a hair had been pressed deep into it.

And they went and told the king, and the king said to them:

“Look and see if there is not something under the mattresses.”

So they went and examined the bottom of the mattresses one by one, and they found a hair in the middle of the bedstead underneath them all. And they took it and showed it to the king; and they also brought the man who was fastidious about beds, and when the king saw the state of his body[4] he was astonished. And he spent the whole night in wondering how a hair could have made so deep an impression on his skin through seven mattresses.

And the next morning the king gave three hundred thousand gold pieces to those three fastidious men, because they were persons of wonderful discernment and refinement. And they remained in great comfort in the king’s court, forgetting all about the turtle; and little did they reck of the fact that they had incurred sin by obstructing their father’s sacrifice.[5]

163g. King Trivikramasena and the Mendicant

When the Vetāla, seated on the shoulder of the king, had told him this wonderful tale, he again asked him a question in the following words:

“King, remember the curse I previously denounced, and tell me which was the most fastidious of these three, who were respectively fastidious about eating, the fair sex, and beds?”

When the wise king heard this, he gave the Vetāla the following answer:

“I consider the man who was fastidious about beds, in whose case imposition was out of the question, the most fastidious of the three, for the mark produced by the hair was seen conspicuously manifest on his body, whereas the other two may have previously acquired their information from someone else.”

When the king said this, the Vetāla left his shoulder, as before, and the king again went in quest of him, as before, without being at all depressed.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

See Appendix, pp. 285-294.—n.m.p.

[2]:

See Vol. V, p. 114n2.—n.m.p.

[3]:

Niyogajanitas is a misprint for niyogijanatas, as is evident from the Sanskrit College MS.

[4]:

Read āṅkam instead of āṅgam. The king was astonished on beholding that mark. —n.m.p.

[5]:

The B. text here is corrupt owing to the improper expression—yajñārthaṃ helopārjita-pātakāh. The reading in the D. text would give us the meaning: “... though they had incurred sin by obstructing the success of their father’s sacrifice.” See Speyer, op. cit., p. 135.— n.m.p.