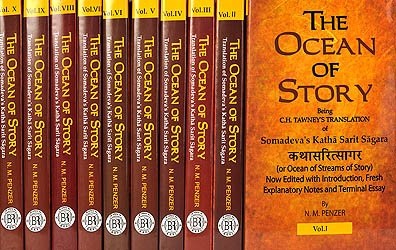

Kathasaritsagara (the Ocean of Story)

by Somadeva | 1924 | 1,023,469 words | ISBN-13: 9789350501351

This is the English translation of the Kathasaritsagara written by Somadeva around 1070. The principle story line revolves around prince Naravāhanadatta and his quest to become the emperor of the Vidhyādharas (‘celestial beings’). The work is one of the adoptations of the now lost Bṛhatkathā, a great Indian epic tale said to have been composed by ...

Chapter LXXIII

163. Story of Mṛgāṅkadatta

THEN Guṇākara’s wounds healed, and he recovered his health, so Mṛgāṅkadatta took leave of his friend the King of the Śavaras, and set out from his town on a lucky day for Ujjayinī, to find Śaśāṅkavatī.

But his friend followed him a long way with his retinue, accompanied by his ally Durgapiśāca, King of the Mātaṅgas, and made a promise to come to his assistance. And as he was going along with his friends Śrutadhi, and Vimalabuddhi, and Guṇākara, and Bhīmaparākrama, and searching for his other friends in that Vindhya forest, it happened that he slept one day on the road with his ministers at the foot of a certain tree. And he suddenly awoke, and got up, and looked about him, and beheld there another man asleep. And when he uncovered his face, [see notes on the effect of moonlight] he recognised him as his own minister Vicitrakatha, who had arrived there. And Vicitrakatha too woke up, and saw his master Mṛgāṅkadatta, and joyfully embraced his feet. And the prince embraced him, with eyes wide open with delight at seeing him so unexpectedly, and all his ministers woke up and welcomed him.

Then all in turn told him their adventures, and asked him to tell his, and Vicitrakatha began to relate his story as follows:

“At that time, when you were dispersed in all directions by the curse of Pārāvatākṣa, I too in my bewilderment wandered about alone for a long time. And after I had roamed far, still unconscious, I suddenly reached in the course of the next day, when I was tired out, a great and heavenly town on the outskirts of the forest. There a godlike being, accompanied by two consorts, beheld me, and had me bathed with cool water, and restored my strength. And he made me enter his city, and carefully fed me with heavenly food; then he ate himself, and those two wives of his ate after him.

And after the meal,[1] being refreshed, I said to him:

‘Who are you, sir, and why have you thus saved the life of me, who am resolved on death? For I must certainly abandon the body, as I have lost my master.’

When I had said this, I told him my whole story. Then that noble and kind being said to me:

‘I am a Yakṣa, these are my wives, and you have come here to-day as my guest, and you know that it is the duty of householders to honour guests to the utmost of their power. I have accordingly welcomed you. But why do you wish to abandon the body? For this separation of yours is due to the curse of a Nāga, and will last only a short time. And you will certainly be all reunited, when the curse pronounced on you has spent its force. And reflect, my good man: who is born free from sorrow in this world? Hear what sorrow I have gone through, though I am a Yakṣa.

163e. Śrīdarśana’s Story

There is a city named Trigartā, the garland that adorns the head of this bride the earth, strung with virtues as with flowers.[2] In it there lived a young Brāhman named Pavitradhara, who was himself poor in worldly wealth, but rich in relations, high birth, and other advantages.

That high-spirited Brāhman, living in the midst of rich people, reflected:

“Though I live up to the rules of my caste, I do not cut a good figure in the midst of these rich people, like a word without meaning[3] among the words of some splendid poem; and being a man of honour, I cannot have recourse to service or donations. So I will go into some out-of-the-way place and get into my power a Yakṣiṇī,[4] for my spiritual teacher taught me a charm for accomplishing this.”

Having formed this resolution, the Brāhman Pavitradhara went to the forest, and according to the prescribed method he won for himself a Yakṣiṇī, named Saudāminī. And when he had won her, he lived united with her, like a banyan-tree, that has tided through a severe winter, united to the glory of spring.

One day the Yakṣiṇī, seeing her husband Pavitradhara in a state of despondency, because no son had been born to him, thus addressed him:

“Do not be despondent, my husband, for a son shall be born to us. And now hear this story which I am about to tell you.

163ee. Saudāminī’s Story

There is on the confines of the southern region a range of tamāla forests, dark with clouds that obscure the sun, looking like the home of the monsoon. In it dwells a famous Yakṣa of the name of Pṛthūdara, and I am his only daughter, Saudāminī by name. My loving father led me from one mighty mountain to another, and I was for ever amusing myself in heavenly gardens.

And one day, as I was sporting on Mount Kailāsa with my friend Kapiśabhrū, I saw a young Yakṣa named Aṭṭahāsa. He too, as he stood among his companions, beheld me; and immediately our eyes were mutually attracted by one another’s beauty. When my father saw that, and ascertained that the match would be no mésalliance, he summoned Aṭṭahāsa, and arranged our marriage. And after he had fixed an auspicious day, he took me home, and Aṭṭahāsa returned to his home with his friends in high spirits.

But the next day my friend Kapiśabhrū came to me with a downcast air, and when I questioned her, she was at length induced to say this:

“Friend, I must tell you this bad news, though it is a thing which should not be told. As I was coming to-day, I saw your betrothed Aṭṭahāsa in a garden named Citrasthala, on a plateau of the Himālayas, full of longing for you. And his friends, in order to amuse him, made him in sport King of the Yakṣas, and they made his brother Dīptaśikha personate Naḍakūvara his son, and they themselves became his ministers. While your beloved was being solaced in this way by his friends, Naḍakūvara, who was roaming at will through the air, saw him.

And the son of the King of Wealth, being enraged at what he saw, summoned him, and cursed him in the following words:

‘Since, though a servant, you desire to pose as a lord, become a mortal, you villain! As you wish to mount, fall!’

When he had laid this curse on Aṭṭahāsa, he answered despondingly:

‘Prince, I foolishly did this to dispel my longing, not through aspiring to any lofty rank, so have mercy upon me.’

When Naḍakūvara heard this sorrowful speech of his, he ascertained by meditation that the case was so, and said to him by way of fixing an end for the curse[5]:

‘You shall become a man, and beget on that Yakṣiṇī, with whom you are in love, your younger brother Dīptaśikha by way of son,[6] and so you shall be delivered from your curse, and obtain your own rank once more, together with your wife, and this brother of yours shall be born as your son, and after he has reigned on earth, he shall be released from his curse.’

When the son of the God of Wealth had said this, Aṭṭahāsa disappeared somewhere or other by virtue of the curse. And when I saw that, my friend, I came here to you grieved.”

When my friend said this to me, I was reduced to a terrible state by grief, and after I had bewailed my lot, I went and told it to my parents, and I spent that time in hope of a reunion with my beloved.

163e. Srīdarśanás Story

“You are Aṭṭahāsa born again as a Brāhman, and I am that Yakṣiṇī, and we have been thus united here, so we shall soon have a son born to us.”

When the Brāhman Pavitradhara’s wise wife Saudāminī said this to him, he conceived the hope that he would have a son, and was much delighted. And in course of time a son was born to him by that Yakṣiṇī, whose birth cheered up their house and his mind. And when Pavitradhara saw the face of that son, he immediately assumed a celestial shape and became again the Yakṣa Aṭṭahāsa.

And he said to that Yakṣiṇī:

“My dear, our curse is at an end. I have become Aṭṭahāsa as before, come, let us return to our own place.”

When he said this, his wife said to him:

“Think what is to become of the child, your brother, who through a curse has been born as your son.”

When Aṭṭahāsa heard that, he saw what was to be done by means of his powers of contemplation, and said to her:

“My dear, there is in this town a Brāhman of the name of Devadarśana. He is poor in children and in wealth, and, though he keeps up five fires, hunger makes two others burn more fiercely—namely, the fire of digestion in his own stomach and in that of his wife.

And one day, as he was engaged in asceticism to obtain wealth and a son, the holy God of Fire, whom he was propitiating, said to him in a dream:

‘You have not a son of your own, but you shall have an adopted son, and by means of him, Brāhman, your poverty shall come to an end.’

On account of this revelation of the God of Fire, the Brāhman is at the present moment expecting that son, so we must give him this child of ours, for this is the decree of fate.”

After Aṭṭahāsa had said this to his beloved, he placed the child on the top of a pitcher full of gold, and fastened round its neck a garland of heavenly jewels, and deposited it in the house of that Brāhman at night when he and his wife were asleep, and then went with his beloved to his own place.

Then the Brāhman Devadarśana and his wife woke up, and beheld that young moon of a child glittering with resplendent jewels, and the Brāhman thought in his astonishment: “What can be the meaning of this?” but when he saw the pot of gold he remembered what the God of Fire had told him in his dream, and rejoiced. And he took that young son given him by fate, and that wealth, and in the morning he made a great feast. And on the eleventh day he gave the child the appropriate name of Śrīdarśana.[7] Then the Brāhman Devadarśana, having become very rich, remained performing his sacrificial and other ceremonies, and enjoying the good things of this world at the same time.

The brave Śrīdarśana grew up in his father’s house, and acquired great skill in the Vedas and other branches of learning, and in the use of weapons. But in course of time, when he had grown up, his father Devadarśana, who had gone on a pilgrimage to sacred bathing-places, died at Prayāga. His mother, hearing of that, entered the fire, and then Śrīdarśana mourned for them, and performed on their behalf the ceremonies enjoined in the sacred treatises. But in course of time his grief diminished, and as he was not married, and had no relations, he became, though well educated, devoted to gambling. And in a short time his wealth was consumed by means of that vice, and he had difficulty in obtaining even food.

One day, after he had remained in the gambling-hall without food for three days, being unable to go out for shame, as he had not got a decent garment to wear, and refusing to eat the food which others gave him, a certain gambler, named Mukharaka, who was a friend of his, said to him:

“Why are you so utterly overwhelmed? Do you not know that such is the nature of the sinful vice of gambling? Do you not know that the dice are the sidelong loving looks of the Goddess of Ill Luck? Has not Providence ordained for you the usual lot of the gambler? His arms are his only clothing, the dust is his bed, the cross-roads are his house, ruin is his wife.[8] So why do you refuse to take food? Why do you neglect your health, though you are a wise man? For what object of desire is there that a resolute man cannot obtain, as long as he continues alive? Hear in illustration of this truth the following wonderful story of Bhūnandana.

163eee. The Adventures of King Bhūnandana

There is here a region named Kaśmīra, the ornament of the earth, which the Creator made as a second heaven, after creating the first heaven, for men who have done righteous deeds. The difference between the two is that in heaven delights can only be seen, in Kaśmīra they can be actually enjoyed.

The two glorious goddesses Srī and Sarasvatī both frequent it, as if they vied with one another, saying:

“I have the pre-eminence here.”

“No, it is I.”

The Himālaya encircles it with its embrace, as if to prevent Kali, the adversary of virtue, from entering it.

The Vitastā adorns it, and repels sin with its waves, as if they were hands, and seems to say:

“Depart far from this land which is full of waters sacred to the gods.”

In it the long lines of lofty palaces, whitened with silvery plaster, imitate the cliffs at the foot of the neighbouring Himālaya. In this land there lived a king, named Bhūnandana, who upheld as a spiritual guide the system of the castes and the prescribed stages of life, learned in science and traditional lore, the moon that delighted his subjects. His valour was displayed in the kingdoms of his foes, on which he left the impress of his nails. He was a politic governor, and his people were ever free from calamity; he was exclusively devoted to Kṛṣṇa, and the minds of his people took no pleasure in vicious deeds.[9]

Once on a time, on the twelfth day of the month, the king, after duly worshipping Viṣṇu, saw in a dream a Daitya maiden approach him.

When he woke up he could not see her, and in his astonishment he said to himself:

“This is no mere dream; I suspect she is some celestial nymph by whom I have been cajoled.”

Under this impression he remained thinking of her, and so grieved at being deprived of her society that gradually he neglected all his duties as a king.

Then that king, not seeing any way of recovering her, said to himself:

“My brief union with her was due to the favour of Viṣṇu, so I will go into a solitary place and propitiate Viṣṇu with a view of recovering her, and I will abandon this clog of a kingdom, which without her is distasteful.”

After saying this, King Bhūnandana informed his subjects of his resolution, and gave the kingdom to his younger brother named Sunandana.

But after he had resigned the kingdom he went to a holy bathing-place named Kramasaras; which arose from the footfall of Viṣṇu, for it was made by him long ago in his Dwarf incarnation.[10] It is attended by the three gods Brahmā, Viṣṇu, and Śiva, who have settled on the top of the neighbouring mountains in the form of peaks. And the foot of Viṣṇu created here in Kaśmīra another Ganges, named Ikṣuvatī, as if in emulation of the Vitastā. There the king remained, performing austerities, and pining without desire for any other enjoyment, like the chātaka in the hot season longing for fresh rain-water.

And after twelve years had passed over his head, while he remained engaged in ascetic practices, a certain ascetic came that way who was a chief of sages: he had yellow matted hair, wore tattered garments, and was surrounded by a band of pupils; and he appeared like Śiva himself come down from the top of the hills that overhang that holy bathing-place. As soon as he saw the king he was filled with love for him, and went up to him, and, bowing before him, asked him his history, and then reflected for a moment and said:

“King, that Daitya maiden that you love lives in Pātāla, so be of good cheer, I will take you to her. For I am a Brāhman named Bhūrivasu, the son of a sacrificing Brāhman of the Deccan, named Yajuḥ, and I am a chief among magicians. My father communicated his knowledge to me, and I learned from a treatise on Pātāla the proper charms and ceremonies for propitiating Hāṭakeśāna.[11]

And I went to Śrīparvata and performed a course of asceticism there for propitiating Śiva, and Śiva, being pleased with it, appeared to me and said to me:

‘Go; after you have married a Daitya maiden and enjoyed pleasures in the regions below the earth, you shall return to me; and listen; I will tell you an expedient for obtaining those delights. There are on this earth many openings leading to the lower regions; but there is one great and famous one in Kaśmīra made by Maya, by which Uṣā the daughter of Bāṇa introduced her lover Aniruddha into the secret pleasure-grounds of the Dānavas, and made him happy there. And Pradyumna, in order to deliver his son, laid it open, making a door in one place with the peak of a mountain, and he placed Durgā there, under the name of Śārikā, to guard that door, after propitiating her with hundreds of praises. Consequently even now the place is called by the two names of Peak of Pradyumna and Hill of Śārikā. So go and enter Pātāla with your followers by that famous opening, and by my favour you shall succeed there.’

“When the god had said this, he disappeared, and by his favour I acquired all the knowledge at once, and now I have come to this land of Kaśmīra. So come with us, King, to that seat of Śārikā, in order that I may conduct you to Pātāla, to the maid that you love.”

When the ascetic had said this to King Bhūnandana, the latter consented, and went with him to that seat of Śārikā. There he bathed in the Vitastā, and worshipped Gaṇeśa, and honoured the goddess Śārikā, and performed the ceremony of averting evil spirits from all quarters by waving the hand round the head[12] and other ceremonies. And then the great ascetic, triumphing by the favour of the boon of Śiva, revealed the opening by scattering mustard-seeds in the prescribed manner, and the king entered with him and his pupils, and marched along the road to Pātāla for five days and five nights.[13] And on the sixth day they all crossed the Ganges of the lower regions, and they beheld a heavenly grove on a silver plain. It had splendid coral, camphor, sandal and aloes trees, and was perfumed with the fragrance of large full-blown golden lotuses. And in the middle of it they saw a lofty temple of Śiva. It was of vast extent, adorned with stairs of jewels; its walls were of gold, it glittered with many pillars of precious stone; and the spacious translucent body of the edifice was built of blocks of the moon-gem.

Then King Bhūnandana and the pupils of that ascetic, who possessed supernatural insight, were cheered, and he said to them:

“This is the dwelling of the god Śiva, who inhabits the lower regions in the form of Hāṭakeśvara, and whose praises are sung in the three worlds, so worship him.”

Then they all bathed in the Ganges of the lower regions, and worshipped Śiva with various flowers, the growth of Pātāla. And after the brief refreshment of worshipping Śiva, they went on and reached a splendid lofty jambu tree,[14] the fruits of which were ripe and falling on the ground. And when the ascetic saw it, he said to them:

“You must not eat the fruits of this tree, for, if eaten, they will impede the success of what you have in hand.”

In spite of his prohibitions one of his pupils, impelled by hunger, ate a fruit of the tree, and, as soon as he had eaten it, he became rigid and motionless.[15]

Then the other pupils, seeing that, were terrified, and no longer felt any desire to eat the fruit; and that ascetic, accompanied by them and King Bhūnandana, went on only a kos[16] farther, and beheld a lofty golden wall rising before them, with a gate composed of a precious gem. On the two sides of the gate they saw two rams with bodies of iron, ready to strike with their horns, put there to prevent anyone from entering. But the ascetic suddenly struck them a blow on their heads with a charmed wand, and drove them off somewhere, as if they had been struck by a thunderbolt. Then he and his pupils and that king entered by that gate, and beheld splendid palaces of gold and gems. And at the door of every one they beheld warders terrible with many teeth and tusks,[17] with iron maces in their hands. And then they all sat down there under a tree, while the ascetic entered into a mystic contemplation to avert evil. And by means of that contemplation all those terrible warders were compelled to flee from all the doors, and disappeared.

And immediately there issued from those doors lovely women with heavenly ornaments and dresses, who were the attendants of those Daitya maidens. They approached separately all there present, and the ascetic among them, and invited them in the name of their mistresses into their respective palaces.

And the ascetic, having now succeeded in his enterprise, said to all the others:

“You must none of you disobey the command of your beloved after entering her palace.”

Then he entered with a few of those attendants a splendid palace, and obtained a lovely Daitya maiden and the happiness he desired. And the others singly were introduced into magnificent palaces by other of the attendants, and were blessed with the love of Daitya maidens.

And the King Bhūnandana was then conducted by one of the attendants, who bowed respectfully to him, to a palace built of gems outside the wall. Its walls of precious stones were, so to speak, adorned all round with living pictures, on account of the reflections on them of the lovely waiting-women. It was built on a platform of smooth sapphire, and so it appeared as if it had ascended to the vault of heaven, in order to outdo a sky-going chariot.[18] It seemed like the house of the Vṛṣṇis,[19] made rich by means of the power of Viṣṇu. In it sported fair ones wild with intoxication, and it was full of the charming grace of Kāma. Even a flower, that cannot bear the wind and the heat, would in vain attempt to rival the delicacy of the bodies of the ladies in that palace. It resounded with heavenly music, and when the king entered it he beheld once more that beautiful Asura maiden whom he had seen in a dream. Her beauty illuminated the lower world which has not the light of the sun or the stars, and made the creation of sparkling jewels, and other lustrous things, an unnecessary proceeding on the part of the Creator.[20]

The king gazed with tears of joy on that indescribably beautiful lady, and, so to speak, washed off from his eyes the pollution which they had contracted by looking at others. And that girl, named Kumudinī, who was being praised by the songs of female attendants,[21] felt indescribable joy when she saw the prince.

She rose up, and took him by the hand and said to him, “I have caused you much suffering,” and then with all politeness she conducted him to a seat. And after he had rested a little while he bathed, and the Asura maiden had him adorned with robes and jewels, and led him out to the garden to drink. Then she sat down with him on the brink of a tank filled with wine, and with the blood and fat of corpses, that hung from trees on its banks, and she offered that king a goblet, full of that fat and wine, to drink, but he would not accept the loathsome compound.

And she kept earnestly saying to the king:

“You will not prosper if you reject my beverage.”

But he answered:

“I certainly will not drink that undrinkable compound, whatever may happen.”

Then she emptied the goblet on his head and departed; and the king’s eyes and mouth were suddenly closed, and her maids took him and flung him into the water of another tank.

And the moment he was thrown into the water he found himself once more in the grove of ascetics, near the holy bathing-place of Kramasaras, where he was before.[22] And when he saw the mountain there, as it were, laughing at him with its snow,[23] the disappointed king, despondent, astonished, and bewildered, reflected as follows:

“What a difference there is between the garden of the Daitya maiden and this mountain of Kramasaras. Ah! what is this strange event? Is it an illusion or a wandering of the mind? But what other explanation can there be than this, that undoubtedly this has befallen me because, though I heard the warning of the ascetic, I disobeyed the injunction of that fair one. And after all the beverage was not loathsome; she was only making trial of me; for the liquor, which fell upon my head, has bestowed on it heavenly fragrance. So it is indubitable that, in the case of the unfortunate, even great hardships endured bring no reward, for Destiny is opposed to them.”

While King Bhūnandana was engaged in these reflections, bees came and surrounded him on account of the fragrant perfume of his body, that had been sprinkled with the liquor offered by the Asura maiden.

When those bees stung the king he thought to himself:

“Alas! so far from my toils having produced the desired fruit, they have produced disagreeable results, as the raising of a Vetāla does to a man of little courage.”[24]

Then he became so distracted that he resolved on suicide.

And it happened that, at the very time, there came a young hermit that way, who, finding the king in this state, and being of a merciful disposition, went up to him and quickly drove away the bees, and after asking him his story said to him:

“King, as long as we retain this body, how can woes come to an end? So the wise should always pursue without distraction the great object of human existence. And until you perceive that Viṣṇu, Śiva and Brahmā are really one, you will always find the successes that are gained by worshipping them separately short-lived and uncertain. So meditate on Brahmā, Viṣṇu and Śiva, in the light of their unity, and patiently perform asceticism here for another twelve years. Then you shall obtain that beloved, and eventually everlasting salvation; and observe, you have already attained a body possessing heavenly fragrance. Now receive from me this skin of a black antelope, to which a charm is attached, and if you wrap yourself up in it you will not be annoyed here by bees.”

When the hermit had said this, he gave him the deerskin and the charm, and departed; and the king accepted his advice, and taking to himself patience, so lived in that place. And after the king had lived there twelve years, and propitiated Śiva by penance, that Daitya maiden, named Kumudinī, came to him of her own accord. And the king went with that beloved to Pātāla, and after he had lived with her a long time in happiness, he attained salvation.

163e. Śrīdarśana’s Story

“So those fortunate ones, whose characters are free from perturbation, and who betake themselves to patient endurance, obtain again their own rank, though they may have fallen far from it.[25] And since you, Śrīdarśana, are a man fated to be prosperous, being covered with auspicious marks, why do you, out of perturbation, allow yourself to go without food?”

When Śrīdarśana, who was fasting, was thus addressed in the gambling-hall by his friend Mukharaka, he said to him:

“What you say is true; but being a man of good family, I cannot for shame go out into this town, as I am reduced so low by gambling. So if you will permit me, my friend, to go to some other country this very night, I will take food.”

When Mukharaka heard that, he consented, and brought food and gave it to him, and he ate it. And after Śrīdarśana had eaten it, he set out for another country with that friend of his, who followed him out of affection.

And as he was going along the road at night, it happened that the two Yakṣas, Aṭṭahāsa and Saudāminī, his father and mother, who had deposited him, as soon as he was born, in the house of the Brāhman, saw him while they were roaming through the air. When they saw him in distress, impoverished by the vice of gambling, and on his way to a foreign country, affection made them say to him, while still remaining invisible, the following words:

“Śrīdarśana, your mother, the wife of Devadarśana, buried in her house some jewels. Take those, and do not omit to go with them to Mālava, for there is a magnificent prince there of the name of Śrīsena. And since he was much afflicted in his youth by miseries arising from gambling, he has made a large and glorious asylum for gamblers. There gamblers live, and are fed with whatever food they desire. So go there, darling, and you shall be prosperous.”

When Śrīdarśana heard this speech from heaven, he went back to his house with his friend, and found those ornaments in it, in a hole in the ground. Then he set out delighted for Mālava, with his friend, thinking that the gods had shown him favour. So in that night and the succeeding day he went a long distance, and the next evening he reached with his friend a village named Bahusasya. And being weary, he sat down with his friend on the bank of a translucent lake, not far from that village. While he remained for a brief period on the bank of that lake, after washing his feet and drinking water, there came there a certain maiden, matchless in beauty, to fetch water. Her body resembled a blue lotus in colour, and she seemed like Rati left alone, and blackened by the smoke from the body of the God of Love, when he had just been consumed by Śiva.

Śrīdarśana was delighted to behold her, and she went up to him, and looked at him with an eye full of love, and said to him and his friend:

“Worthy sirs, why have you come hither to your death? Why, through ignorance, have you fallen like moths into burning fire?”

When Mukharaka heard this, he said to the maiden, without the least trepidation:

“Who are you? And what is the meaning of what you say? Tell us.”

Then she said: “Listen, both of you! I will tell you the whole story in few words.

“There is a large and famous royal grant to Brāhmans named Sughoṣa. In it there dwelt a Brāhman named Padmagarbha, who possessed a thorough knowledge of the Vedas. He had a wife of very good family, named Śaśikalā. And the Brāhman had two children by that wife, a son of the name of Mukharaka, and myself, a daughter of the name of Padmiṣṭhā. My brother Mukharaka was ruined by the vice of gambling in early youth, and left his home and went off to some other country. My mother died of grief on that account, and my father, afflicted with two sorrows, abandoned the state of a householder. And he roamed about from place to place, with no other companion than myself, to look for that son, and, as it happened, he reached this village. Now in this village there lives a great bandit, the chief of a gang of robbers, called Vasubhūti, a Brāhman only by name. When my father arrived here, that ruffian, with the help of his servants, killed him, and took away the gold he had about his person. And he made me a prisoner and carried me off to his house, and he has made arrangements to give me in marriage to his son Subhūti. But his son has gone off somewhere to plunder a caravan, and, owing to my good fortune, the result of good deeds in a former birth, he has not yet returned; now it remains for Destiny to dispose of me. But, if this bandit were to see you, he would certainly do you some violence: so think of some artifice by which you may escape him.”

When the maiden said this, Mukharaka recognised her, and at once clasping her round the neck said to her:

“Alas, my sister Padmiṣṭhā! I am that very brother of yours, Mukharaka, the murderer of his relations. Alas! wretched that I am, I am ruined.”

When Padmiṣṭhā heard this, and saw her elder brother, pity caused her to be, as it were, suddenly encircled with all sorrows. Then Śrīdarśana comforted the brother and sister, who were lamenting their parents, and addressed a timely admonition and encouragement to them.

He said:

“This is not the time for lamentation; we must save now our lives even at the cost of our wealth, and by means of it we must protect ourselves against this bandit.”

When Śrīdarśana said this, they checked their grief with self-control, and all agreed together what each was to do.

Then Śrīdarśana, being thin by reason of his former fasts, flung himself down on the bank of that tank, and pretended to be ill. And Mukharaka remained holding his feet and weeping: but Padmiṣṭhā immediately repaired to that bandit chief, and said:

“A traveller has arrived, and is lying ill on the border of the tank, and there is another there who is his servant.”

When the bandit chief heard that, he sent some of his followers there. They went, and, seeing the two men as had been described, asked Mukharaka why he wept so much for his companion.

When Mukharaka heard this, he said with affected sorrow:

“This Brāhman, who is my elder brother, left his native land to visit holy bathing-places, but was attacked by disease, and slowly travelling along he has arrived here, accompanied by me.

And the moment he got here he became incapable of movement, and he said to me:

‘Rise up, my dear brother, and quickly prepare for me a bed of darbha grass. And fetch me some virtuous Brāhman from this village. On him I will bestow all my wealth, for I cannot live through this night.’

When he said this to me, in this foreign country after sunset, I felt quite puzzled as to what I ought to do, and, being afflicted, I had recourse to weeping. So bring here some Brāhman while he is alive, in order that he may bestow on him with his own hand whatever wealth we possess. For he will certainly not live through the night, and I shall not be able to survive the sorrow of his loss, so to-morrow I shall enter the fire. So do for us this which we ask, since we have met with you here as compassionate men and friends without any cause.”

When the bandits heard that, pity arose in their minds, and they went and told the story, exactly as they had heard it, to their master Vasubhūti, and went on to say:

“So come and receive, as a pious gift, from this Brāhman, who is eager to bestow it on you, the wealth which ordinarily is to be obtained only by killing its possessor.”

When they said this to Vasubhūti he said:

“What course is this which you suggest? It is highly impolitic for us to take wealth without killing its possessor, for, if he is deprived of his wealth without being killed, he will certainly do us an injury.”

When the villain said this, those servants answered him:

“What is there to fear in this? There is some difference in taking wealth by force, and receiving it as a gift from a dying man. Besides, to-morrow morning we will kill these two Brāhmans, if they are still alive. Otherwise, what is the use of incurring needlessly the guilt of killing a Brāhman?”

When Vasubhūti heard this he consented, and in the night he came to Śrīdarśana to receive his pious gift, and Śrīdarśana concealed a part of his mother’s ornaments, and gave him the rest, assuming a faltering voice. Then the bandit, having got what he wanted, returned home with his followers.

Then Padmiṣṭhā came at night to Śrīdarśana and Mukharaka, while the bandits were asleep. Then they quickly deliberated together, and set off at once from that place for Mālava by a path not frequented by the robbers. And during that night they went a long distance, and reached a wood that seemed to be afraid of the roaring lions, tigers and other wild beasts within it. It seemed by its thorns to be in a state of perpetual horripilation, and by its roaming black antelopes to be rolling its eyes. The dry creepers showed that its body was dried up from fear, and the shrill whistling of the loose bark was its screams of terror. And while they were journeying through the forest, the sun, that had observed their sufferings all day, withdrew its light as if in compassion, and set.

Then they sat down weary and hungry at the foot of a tree, and in the early part of the night they saw in the distance a light, as of fire.

And Śrīdarśana said:

“Can there possibly be a village here? I will go and look.”

So he went in the direction of the light. And when he reached it, and looked at it, lo! it was a great palace of jewels, and its splendour produced that light as of fire.[26] And he saw inside it a Yakṣiṇī of heavenly beauty, surrounded by many Yakṣas, with feet turned the wrong way and squinting eyes. And the brave man, seeing that they had brought there all kinds of meat and drink, went up to the Yakṣiṇī, and asked her to give him his share as a guest. And she was pleased with his courage and gave him what he asked for: enough food and water to satisfy himself and his two companions. The refreshment was placed on the back of a Yakṣa ordered off by her for that duty, and Śrīdarśana returned with it to his friend and Padmiṣṭhā. And then he dismissed the Yakṣa, and partook there with them of all that splendid food of various kinds, and drank pure cold water.

Then Mukharaka was pleased, perceiving that he must be an incarnation of a divinity, as he was so rich in courage and might, and, desiring his own prosperity, he said to him:

“You are some incarnation of a divinity, and this sister of mine, Padmiṣṭhā, is the greatest beauty in the world, so I now give her to you as a wife meet for you.”

When Śrīdarśana heard that, he was delighted, and said to his friend:

“I accept with joy this offer of yours, which I have long desired. But when I reach my goal I will marry her in proper form.”

This he said to those two, and then passed the night in a joyful state of mind. And the next morning they all set out from that place, and reached in due course the city of that King Śrīsena, the sovereign of Mālava. And arriving tired, they immediately entered the house of an old Brāhman woman to rest.

And in the course of conversation they told her their story and their names; and then they saw that the old woman was much disturbed, and when they questioned her she said to them:

“I am the well-born wife of a Brāhman here, named Satyavrata, who was a servant of the king’s, and my name is Yaśasvatī. And after my husband died, the compassionate king gave me the fourth part of his salary to live upon, as I had not a son to support me. But now this moon of kings, though his virtues are great, and though he is generous enough to give away the whole world, has been seized by a consumption[27] which the physicians cannot cure. And the drugs and charms of those skilled in such things do not prevail against it; but a certain enchanter made this promise in his presence:

‘If I could only get a hero, equal to the task, to help me, I would certainly put an end to this illness by getting a Vetāla into my power.’

Then proclamation was made by beat of drum, but no such hero was found. Then the king gave the following order to his ministers:

‘You must look out for some daring gambler, who comes to reside in the great and well-known asylum which I built for such. For gamblers are reckless, abandoning wife and relations, fearless, sleeping at the foot of trees and in other exposed places, like ascetics.’

When the king gave this order to his ministers, they instructed to this effect the superintendent of the asylum, and he is now on the look-out for some brave man who may come there to reside awhile. Now you are gamblers, and if you, Śrīdarśana, feel able to accomplish the undertaking, I will take you to-day to that asylum. And you will be well treated by the king, and you will confer a benefit on me, for grief is killing me.”

When the old lady said this, Śrīdarśana answered her:

“Agreed! I am able to accomplish this, so lead me quickly to that asylum.”

When she heard this, she took him, and Padmiṣṭhā, and Mukharaka, to that asylum, and there said to the superintendent:

“Here is a Brāhman gambler arrived from a foreign land, a hero who is able to assist that enchanter in performing incantations for the good of the king.”

When the superintendent heard this, he questioned Śrīdarśana, and when he confirmed the words of the old lady he treated him with great respect, and led him quickly into the presence of the king.

And Śrīdarśana, being introduced by him, beheld the king, who was thin and pale as the new moon. And King Śrīsena observed that Śrīdarśana, who bowed before him and sat down, was of a taking appearance, and, pleased with his look, he felt comforted, and said to him:

“I know that your exertions will certainly put an end to my disease; my body tells me this, for the mere sight of you has quieted its sufferings. So aid the enchanter in this matter.”

When the king said this, Śrīdarśana said to him:

“The enterprise is a mere trifle.”

Then the king summoned the enchanter, and said to him:

“This hero will aid you; do what you said.”

When that enchanter heard that, he said to Śrīdarśana:

“My good sir, if you are able to assist me in raising a Vetāla, come to me in the cemetery at nightfall this very day, the fourteenth of the black fortnight.”

When the ascetic, who practised magic, had said this, he went away, and Śrīdarśana took leave of the king and returned to that asylum.

There he took food with Padmiṣṭhā and Mukharaka, and at night he went alone, sword in hand, to the cemetery. It was full of many ghosts, empty of men, inauspicious, full of roaring jackals, covered with impenetrable darkness, but showed in some places a faint gleam where the funeral pyres were.[28] The hero Śrīdarśana wandered about in that place of horrors and saw the enchanter in the middle of it. His whole body was smeared with ashes, he had a Brāhmanical thread of hair, he wore a turban made of the clothes of the dead, and he was clad in a black garment.

Śrīdarśana approached him, and made himself known to him, and then, girding up his loins, he said:

“Tell me, what shall I do for you?”

The enchanter answered in high spirits:

“Half a kos only to the west of this place there is an aśoka tree, the leaves of which are burned with the hot flame of funeral pyres. At the foot of it there is a corpse; go and bring it here unharmed.”

Then Śrīdarśana said: “I will”; and going quickly to the place he saw someone else taking away the corpse.

So he ran and tried to drag it from the shoulder of that person, who would not let it go, and said to him:

“Let go this corpse: where are you taking my friend whom I have to burn?”

Then that second person said to Śrīdarśana:

“I will not let the dead man go; I am his friend; what have you to do with him?”

While they were dragging the corpse from one another’s shoulders, and making these mutual recriminations, the corpse itself, which was animated by a Vetāla, uttered a terrible shriek. That terrified the second person so that his heart broke, and he fell down dead, and then Śrīdarśana went off with that corpse in his arms.

Then the second man, though dead, rose up, being possessed by a Vetāla, and tried to stop Śrīdarśana, and said to him:

“Halt! do not go off with my friend on your shoulder.”

Then Śrīdarśana, knowing that his rival was possessed by a Vetāla, said to him:

“What proof is there that you are his friend? He is my friend.”

The rival then said:

“The corpse itself shall decide between us.”

Then Śrīdarśana said:

“Well! Let him declare who is his friend.”

Then the corpse that was on his back, being possessed by a Vetāla, said:

“I am hungry, so I decide that whoever gives me food is my friend; let him take me where he likes.”

When the second corpse, that was also possessed by a Vetāla, heard this, he answered:

“I have no food; if he has any, let him give you some.”

Śrīdarśana, hearing this, said: “I will give you food”; and proceeded to strike with his sword at the second corpse, in order to procure food for the Vetāla that was on his shoulder.[29] But that second corpse, which was also possessed by a Vetāla, the moment he began to strike it, disappeared by its supernatural power.

Then the Vetāla that was on Śrīdarśana’s shoulder said to him:

“Now give me the food that you promised me.”

So Śrīdarśana, not being able to obtain any other flesh to give him to eat, cut off with his sword some of his own flesh, and gave it to him.[30] This pleased the Vetāla, and he said to him:

“I am satisfied with you, brave man; let your body be restored whole as before. Now take me off; this enterprise of yours shall succeed, but that ascetic enchanter shall be destroyed, for he is a great coward.”

When Śrīdarśana was thus addressed by the Vetāla, he immediately became whole as before, and taking the corpse he handed it to the magician. He received it joyfully, and honoured it with unguents and garlands of blood, and he placed the corpse, possessed by the Vetāla, on its back in a great circle marked out with powdered human bones, in the corners of which were placed pitchers of blood, and which was lighted up with lamps fed by oil from the human body. And he sat on the breast of the corpse, and holding in his hand a ladle and spoon of human bone, he began to make an oblation of clarified butter in its mouth. Immediately such a flame issued from the mouth of that corpse possessed by the Vetāla that the sorcerer rose up in terror and fled. When he thus lost his presence of mind, and dropped his spoon and ladle, the Vetāla pursued him, and opening his mouth swallowed him whole.[31]

When Śrīdarśana saw that, he lifted up his sword and attacked the Vetāla, but the Vetāla said to him:

“Śrīdarśana, I am pleased with this courage of yours, so take these mustard-seeds produced in my mouth. If you place these on the head and hands of the king, the malady of consumption will immediately leave him, and you in a short time will become the king of the whole earth.”

When Śrīdarśana heard this, he said:

“How can I leave this place without that sorcerer? The king is sure to say that I killed him out of a selfish regard to my own interests.”

When Śrīdarśana said this to the Vetāla, he answered:

“I will tell you a convincing proof, which will clear you. Cut open the body of this corpse, and show inside it this sorcerer dead, whom I have swallowed.”

When the Vetāla had said this, he gave him the mustard-seeds, and went off somewhere or other, leaving that corpse, and the corpse fell on the ground.

Then Śrīdarśana went off, taking with him the mustard-seeds, and he spent that night in the asylum in which his friend was. And the next morning he went to the king, and told him what had happened in the night, and took and showed to the ministers that sorcerer in the stomach of the corpse. Then he placed the mustard-seeds on the head and the hands of the king, and that made the king quite well, as all his sickness at once left him. Then the king was pleased, and, as he had no son, he adopted as his son Śrīdarśana, who had saved his life. And he immediately anointed that hero Crown Prince; for the seed of benefits, sown in good soil, produces abundant fruit. Then the fortunate Śrīdarśana married there that Padmiṣṭhā, who seemed like the Goddess of Fortune that had come to him in reward for his former courting of her, and the hero remained there, in the company of her brother Mukharaka, enjoying pleasures and ruling the earth.

One day a great merchant, named Upendraśakti, found an image of Gaṇeśa, carved out of a jewel, on the border of a tank, and brought it and gave it to that prince. The prince, seeing that it was of priceless value, out of his fervent piety set it up in a very splendid manner in a temple. And he appointed a thousand villages there for the permanent support of the temple, and he ordained in honour of the idol a festive procession, at which all Mālava assembled.

And Gaṇeśa, being pleased with the numerous dances, songs and instrumental performances in his honour, said to the Gaṇas at night:

“By my favour this Śrīdarśana shall be a universal emperor on the earth. Now there is an island named Haṃsadvīpa in the western sea; and in it is a king named Anaṅgodaya, and he has a lovely daughter named Anaṅgamañjarī. And that daughter of his, being devoted to me, always offers to me this petition, after she has worshipped me:

‘Holy one, give me a husband who shall be the lord of the whole earth.’

So I will marry her to this Śrīdarśana, and thus I shall have bestowed on both the meet reward of their devotion to me. So you must take Śrīdarśana there, and after you have contrived that they should see one another, bring him back quickly; and in course of time they shall be united in due form; but it cannot be done immediately, for such is the will of Destiny. Moreover I have determined by these means to recompense Upendraśakti, the merchant, who brought my image to the prince.”

The Gaṇas, having received this order from Gaṇeśa, took Śrīdarśana that very night, while he was asleep, and carried him to Haṃsadvīpa by their supernatural power. And there they introduced him into the chamber of Anaṅgamañjarī and placed him on the bed on which that princess was lying asleep. Śrīdarśana immediately woke up, and saw Anaṅgamañjarī. She was reclining on a bed covered with a quilt of pure white woven silk, in a splendid chamber in which flashed jewel lamps, and which was illuminated by the numerous priceless gems of the canopy and other furniture, and the floor of which was dark with the rājāvarta stone. As she lay there pouring forth rays of beauty like the lovely effluence of a stream of nectar, she seemed like the orb of the autumn moon lapped in a fragment of a white cloud, in a sky adorned with a host of bright twinkling stars, gladdening the eyes.

Immediately he was delighted, astonished and bewildered, and he said to himself:

“I went to sleep at home and I have woke up in a very different place. What does all this mean? Who is this woman? Surely it is a dream! Very well, let it be so. But I will wake up this lady and find out.”

After these reflections he gently nudged Anaṅgamañjarī on the shoulder with his hand. And the touch of his hand made her immediately awake and roll her eyes, as the kumudvatī opens under the rays of the moon, and the bees begin to circle in its cup.

When she saw him, she reflected for a moment:

“Who can this being of celestial appearance be? Surely he must be some god that has penetrated into this well-guarded room?”

So she rose up, and asked him earnestly and respectfully who he was, and how and why he had entered there. Then he told his story, and the fair one, when questioned by him, told him in turn her country, name and descent. Then they both fell in love with one another, and each ceased to believe that the other was an object seen in a dream, and, in order to make certain, they exchanged ornaments.

Then they both became eager for the gāndharva form of marriage,[32] but the Gaṇas stupefied them, and laid them to sleep. And as soon as Śrīdarśana fell asleep they took him and carried him back to his own palace, cheated by Destiny of his desire.

Then Śrīdarśana woke up in his own palace, and seeing himself decked with the ornaments of a lady he thought:

“What does this mean? At one moment I am in that heavenly palace with the daughter of the King of Haṃsadvīpa, at another moment I am here. It cannot be a dream, for here are these ornaments of hers on my wrist, so it must be some strange freak of Destiny.”

While he was engaged in these speculations, his wife Padmiṣṭhā woke up, and questioned him, and the kind woman comforted him, and so he passed the night. And the next morning he told the whole story to Śrīsena, before whom he appeared wearing the ornaments marked with the name of Anaṅgamañjarī. And the king, wishing to please him, had a proclamation made by beat of drum, to find out where Haṃsadvīpa was, but could not find out from anyone the road to that country. Then Śrīdarśana, separated from Anaṅgamañjarī, remained overpowered by the fever of love, averse to all enjoyment. He could not like his food while he gazed on her ornaments, necklace and all, and he abandoned sleep, having ceased to behold within reach the lotus of her face.[33]

In the meanwhile the Princess Anaṅgamañjarī, in Haṃsadvīpa, was awakened in the morning by the sound of music. When she remembered what had taken place in the night, and saw her body adorned with Śrīdarśana’s ornaments, longing love made her melancholy.

And she reflected:

“Alas, I am brought into a state in which my life is in danger, by these ornaments, which prove that I cannot have been deluded by a dream, and fill me with love for an unattainable object.”

While she was engaged in these reflections, her father, Anaṅgodaya, suddenly entered, and saw her wearing the ornaments of a man. The king, who was very fond of her, when he saw her covering her body with her clothes, and downcast with shame, took her on his lap and said to her:

“My daughter, what is the meaning of these masculine decorations, and why this shame? Tell me. Do not show a want of confidence in me, for my life hangs on you.”

These and other kind speeches of her father’s allayed her feeling of shame, and she told him at last the whole story.

Then her father, thinking that it was a piece of supernatural enchantment, felt great doubt as to what steps he ought to take. So he went and asked an ascetic of the name of Brahmasoma, who possessed superhuman powers, and observed the rule of the Pāśupatas, and who was a great friend of his, for his advice.

The ascetic by his powers of contemplation penetrated the mystery, and said to the king:

“The truth is that the Gaṇas brought here Prince Śrīdarśana from Mālava, for Gaṇeśa is favourably disposed both to him and your daughter, and by his favour he shall become a universal monarch. So he is a capital match for your daughter.”

When that gifted seer said this, the king bowed, and said to him:

“Holy seer, Mālava is far away from this great land of Haṃsadvīpa. The road is a difficult one, and this matter does not admit of delay. So in this matter your ever-propitious self is my only stay.”

When the ascetic, who was so kind to his admirers, had been thus entreated by the king, he said, “I myself will accomplish this,” and he immediately disappeared. And he reached in a moment the city of King Śrīsena, in Mālava.

There he entered the very temple built by Śrīdarśana, and, after bowing before Gaṇeśa, he sat down and began to praise him, saying:

“Hail to thee of auspicious form, whose head is crowned with a garland of stars, so that thou art like the peak of Mount Meru! I adore thy trunk flung up straight in the joy of the dance, so as to sweep the clouds, like a column supporting the edifice of the three worlds. Destroyer of Obstacles, I worship thy snake-adorned body, swelling out into a broad pitcher-like belly, the treasure-house of all success.”

While the ascetic was engaged in offering these praises to Gaṇeśa in the temple, it happened that the son of the merchant-prince Upendraśakti, who brought his image, entered the temple as he was roaming about. His name was Mahendraśakti, and he had been rendered uncontrollable by long and violent madness, so he rushed forward to seize the ascetic. Then the ascetic struck him with his hand. The merchant’s son, as soon as he was struck by the charm-bearing hand of that ascetic, was freed from madness and recovered his reason. And as he was naked he felt shame, and left the temple immediately, and covering himself with his hand, he made for his home. Immediately his father, Upendraśakti, hearing of it from the people, met him, full of joy, and led him to his house. There he had him bathed, and properly clothed and adorned, and then he went with him to the ascetic Brahmasoma. And he offered him much wealth as the restorer of his son, but the ascetic, as he possessed godlike power, would not receive it.

In the meanwhile King Śrīsena himself, having heard what had taken place, reverently approached the ascetic, accompanied by Śrīdarśana.

And the king bowed before him, and praised him, and said:

“Owing to your coming, this merchant has received a benefit, by having his son restored to health, so do me a benefit also by ensuring the welfare of this son of mine, Śrīdarśana.”

When the king craved this boon of the ascetic, he smiled and said:

“King, why should I do anything to please this thief, who stole at night the heart and the ornaments of the Princess Anaṅgamañjarī, in Haṃsadvīpa, and returned here with them? Nevertheless I must obey your orders.”

With these words the ascetic seized Śrīdarśana by the forearm, and disappeared with him. He took him to Haṃsadvīpa, and introduced him into the palace of King Anaṅgodaya, with his daughter’s ornaments on him. When Śrīdarśana arrived, the king welcomed him gladly, but first he threw himself at the feet of the ascetic and blessed him. And on an auspicious day he gave Śrīdarśana his daughter Anaṅgamañjarī, as if she were the earth garlanded with countless jewels. And then by the power of that ascetic he sent his son-in-law, with his wife, to Mālava. And when Śrīdarśana arrived there, the king welcomed him gladly, and he lived there in happiness with his two wives.

In the course of time King Śrīsena went to the next world, and that hero took his kingdom and conquered the whole earth. And when he had attained universal dominion he had two sons by his two wives, Padmiṣṭhā and Anaṅgamañjarī. And to one of them the king gave the name of Padmasena, and to the other of Anaṅgasena, and he reared them up to manhood.

And in course of time King Śrīdarśana, as he was sitting inside the palace with his two queens, heard a Brāhman lamenting outside. So he had the Brāhman brought inside, and asked him why he lamented.

Then the Brāhman showed great perturbation and said to him:

“The fire that had points of burning flame (Dīptaśikha) has been now destroyed by a dark cloud of calamity, discharging a loud laugh (Aṭṭahāsa), together with its line of brightness and line of smoke (Jyotirlekhā and Dhūmalekhā).”[34]

The moment the Brāhman had said this he disappeared. And while the king was saying in his astonishment, “What did he say, and where has he gone?” the two queens, weeping copiously, suddenly fell dead.

When the king saw that sudden calamity, terrible as the stroke of a thunderbolt, he exclaimed in his grief, “Alas! alas! what means this?” and fell on the ground wailing. And when he fell, his attendants picked him up and carried him to another place, and Mukharaka took the bodies of the queens and performed the ceremony of burning them. At last the king came to his senses, and after mourning long for the queens, he completed, out of affection, their funeral ceremonies. And after he had spent a day darkened by a storm of tears he divided the empire of the earth between his two sons. Then, having conceived the design of renouncing the world, he left his city, and turning back his subjects who followed him, he went to the forest to perform austerities.

There he lived on roots and fruits; and one day, as he was wandering about at will, he came near a banyan-tree.

As soon as he came near it, two women of celestial appearance suddenly issued from it with roots and fruits in their hands, and they said to him:

“King, take these roots and fruits which we offer.”

When he heard that, he said:

“Tell me now who you are.”

Then those women of heavenly appearance said to him:

“Well, come into our house and we will tell you the truth.”

When he heard that he consented, and entering with them, he saw inside the tree a splendid golden city.

There he rested and ate heavenly fruits, and then those women said to him: “Now, King, hear.

“Long ago there dwelt in Pratiṣṭhāna a Brāhman, of the name of Kamalagarbha, and he had two wives: the name of the one was Pathyā, and the name of the other Abalā. Now in course of time all three, the husband and the wives, were worn out with old age, and at last they entered the fire together, being attached to one another.

And at that time they put up a petition to Śiva from the fire:

‘May we be connected together as husband and wives in all our future lives!’

Then Kamalagarbha, owing to the power of his severe penances, was born in the Yakṣa race as Dīptaśikha, the son of the Yakṣa Pradīptākṣa, and the younger brother of Aṭṭahāsa. His wives too, Pathyā and Abalā, were born as Yakṣa maidens—that is to say, as the two daughters of the king of the Yakṣas named Dhūmaketu—and the name of the one was Jyotirlekhā, and the name of the other Dhūmalekhā.

“Now in course of time those two sisters grew up, and they went to the forest to perform asceticism, and they propitiated Śiva with the view of obtaining husbands.

The god was pleased, and he appeared to them and said to them:

‘That man with whom you entered the fire in a former birth, and who you asked might be your husband in all subsequent births, was born again as a Yakṣa named Dīptaśikha, the brother of Aṭṭahāsa; but he has become a mortal owing to the curse of his master, and has been born as a man named Śrīdarśana, so you too must go to the world of men and be his wives there; but as soon as the curse terminates, you shall all become Yakṣas, husband and wives together.’

When Śiva said this, those two Yakṣa maidens were born on the earth as Padmiṣṭhā and Anaṅgamañjarī. They became the wives of Śrīdarśana, and after they had been his wives for some time, that Aṭṭahāsa, as fate would have it, came there in the form of a Brāhman, and by the device of employing an ambiguous speech he managed to utter their names and remind them of their former existence, and this made them abandon that body and become Yakṣiṇīs. Know that we are those wives of yours, and you are that Dīptaśikha.”

When Śrīdarśana had been thus addressed by them, he remembered his former birth, and immediately became the Yakṣa Dīptaśikha, and was again duly united to those two wives of his.

“‘Know therefore, Vicitrakatha, that I am that Yakṣa, and that these wives of mine are Jyotirlekhā and Dhūmalekhā. So if creatures of godlike descent, like myself, have to endure such alterations of joy and sorrow, much more then must mortals. But do not be despondent, my son, for in a short time you shall be reunited to your master Mṛgāṅkadatta. And I remained here to entertain you, for this is my earthly dwelling. So stay here; I will accomplish your desire, then I will go to my own home in Kailāsa.’

163. Story of Mṛgāṅkadatta

“When the Yakṣa had in these words told me his story, he entertained me for some time. And the kind being, knowing that you had arrived here at night, brought me and laid me asleep in the midst of you who were asleep. So I was seen by you, and you have been found by me. This, King, is the history of my adventures during my separation from you.”

When Prince Mṛgāṅkadatta had heard at night this tale from his minister Vicitrakatha, who was rightly named,[35] he was much delighted, and so were his other ministers.

So, after he had spent that night on the turf of the forest, he went on with those companions of his towards Ujjayinī, having his mind fixed on obtaining Śaśāṅkavatī; and he kept searching for those other companions of his, who were separated by the curse of the Nāga, and whom he had not yet found.

[Additional note 1: food-taboo in the Underworld]

[Additional note 2: on vampires (section B)]

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

I read, with the MS. in the Sanskrit College, bhuktottaram.

[2]:

It also means “the virtues of good or learned men.”

[3]:

It also means “without wealth”; vṛtta also means “metre.”

[4]:

I.e. female Yakṣa.

[5]:

This clearly shows that, even if it has been uttered hastily, a curse once inflicted can never be annulled, only shortened as to its period of operation.— n.m.p.

[6]:

The notion which Lucretius ridicules in his famous lines (Book III, line 776 et seq.),

“Denique conubia ad Veneris partusque ferarum

Esse animas præsto deridiculum esse videtur,

Expectare immortales mortalia membra,” etc.,

would, it is clear, present no difficulty to the mind of a Hindu. Nor would he be much influenced by the argument in lines 670-674 of the same book:

“Præterea si immortalis natura animaï

Constat, et in corpus nascentibus insinuetur,

Cur super anteactam ætatem meminisse nequimus,

Nec vestigia gestarum rerum ulla tenemus?”

[7]:

I.e. vision of the Goddess of Fortune: something like Fortunatus.

[8]:

I read bākū and vidkvastatā: kim tad in śl. 78 should probably be tat kim.

[9]:

In the original there is a most elaborate pun: “free from calamity” may mean also “impolitic” or “lawless.”

[10]:

It was as Vāmana, the dwarf, his fifth incarnation, that Viṣṇu appeared to Bali and asked for as much land as could be covered in three paces. On his request being granted, in two paces he strode over heaven and earth. See R. Shama Sastry, “Viṣṇu’s Three Strides: the Measure of Vedic Chronology,” Bombay Br. Boy. As. Soc., vol. xxvi, pp. 40-56.—n.m.p.

[11]:

A name of Śiva.

[12]:

My native friends tell me that the hand is waved round the head, and the fingers are snapped four or ten times. “This is,” says Crooke (op. cit., vol. ii, p. 24),

“perhaps one explanation of the use of flags at temples and village shrines, though in some cases they appeared to be used as a perch, on which the deity sits when he makes his periodical visits.”

In Upper India the custom at Hindu weddings connected with the waving away of spirits is called Parachhan. Fans and branches of sacred trees are also largely used to dispel spirits, but practically anything passed round the head (usually seven times) and then thrown away, or scattered in all directions, will have the desired effect.—n.m.p.

[13]:

Possibly this story is the same as that of Tannhäuser, for which see Baring-Gould’s Curious Myths of the Middle Ages, pp. 209-229. He remarks that the story of Tannhäuser is a very ancient myth christianised.——The Mountain of Venus appears in German literature before its connection with Tannhäuser, for which see Gottfried von Strassburg, Tristan und Isolde, 1. 4805 et seq. For the Tannhäuser myth itself reference should be made to P. S. Barto, Tannhäuser and the Mountain of Venus, Oxford University Press, New York Branch, 1916, which contains ten pages of useful bibliography. Professor R. Priebsch draws my special attention to E. Elster, Tannhäuser in Geschichte, Sage und Dichtung, Bromberg, 1908; W. Gother, Zur deutschen Sage und Dichtung. Gesammelte Aufsätze, Leipzig, 1911; and F. Rostock, Mittelhochdeutsche Dichterheldensage, Halle, 1925, pp. 12-15, with a good bibliography.—n. m. p.

[14]:

This is the rose-apple, Eugenia jambolana, found throughout India. The bark is used as an astringent, while the seed or stone of the fruit has acquired some reputation as a cure for diabetes. See Kanny Lall Dey, Indigenous Drugs of India, 2nd edition, Calcutta, 1896, p. 123.—n.m.p.

[15]:

See note at the end of the chapter.— n.m.p.

[16]:

See p. 70n1.—n.m.p.

[17]:

The Sanskrit College MS. has dantadṛṣtādharotkaṭān. Perhaps dṛṣṭa should be daṣṭa. It would then mean “terrible because they were biting their lips.”

[18]:

The Sanskrit College MS. reads vimānavijigīṣayā.

[19]:

Descendants of Vṛṣṇi and relatives of Kṛṣṇa. In Achyuta there is a pun: the word may mean “Viṣṇu” and also “permanent”: rāmam may also refer to Balarāma, who is represented as a drunkard.

[20]:

Pātāla, like Milton’s lower world, “wants not her hidden lustre, gems, and gold.”

[21]:

Kumudinī means an assemblage of white water-lilies: female attendants may also mean bees, as the Sandhi will admit of ali or āli: rājendram should probably be rājendum, moon of kings, as the kumudinī loves the moon.

[22]:

Cf. the story of Śaktideva in Vol. II, pp. 223-224; and see p. 279 of this volume.—n.m.p.

[23]:

By the laws of Hindu rhetoric a smile is regarded as white.

[24]:

We have an instance of this a little farther on.

[25]:

I read dūrabhraṣṭā. The reading of the Sanskrit College MS. is dūram bhraṣṭā.

[26]:

See Vol. III, p. l67, l67n2, also Prym and Socin, Syrische Märchen, p. 36, and Southey’s Thalaba the Destroyer, Book I, p. 30, with notes.

[27]:

The moon suffers from consumption in consequence of the curse of Dakṣa, who was angry at his exclusive preference for Rohiṇī.

[28]:

Here there is a pun: upachitam means also “concentrated.”

[29]:

Cf. a story in the Nugœ Curialium of Gualterus Mapes, in which a corpse, tenanted by a demon, is prevented from doing further mischief by a sword-stroke, which cleaves its head to the chin. (Liebrecht’s Zur Volkskunde, p. 34 et seq.)

[30]:

See Vol. I, pp. 84n2, 85n; Vol. II, p. 235. Mention should be made of a group of stories in which the hero gives flesh from his own body to an eagle or other large bird which carries him from the underworld. Grimm No. 91, “Dat Erdmänneken,” can be taken as the standard version, of which numerous variants will be found in Bolte, op. cit., vol. ii, p. 297 et seq. (motif E). In Lorraine the corresponding stories are “Jean de l’Ours” (Cosquin, Contes Populaires de Lorraine, vol. i, pp. 1-27) and “La Canne de Cinq Cents Livres” (ditto, vol. ii, p. 137, and pp. 141-143, where several other variants are given). In a tale from Ulaghátsh, in the Cappadocian area of Asia Minor, called “The Underworld Adventure,” is an interesting variant of the motif. That portion which concerns us is thus translated by R. M. Dawkins (Modern Greek in Asia Minor, Cambridge, 1916, pp. 373-374):

“The mother of the chicks said to the scaldhead [ὁ κασίδης = bald man]: ‘When I say “Lak!” give me water, when I say “Lyk!” give me meat. In this way I will take you out to the surface of the earth.’ The scaldhead put the meat on her wing; the water he put on her other wing. And the scald-head mounted on her. When she says ‘Lak!’ he gives her meat; when she says ‘Lyk!’ he gives her water. Thus and thus she brought him half way. The meat and the water came to an end. ‘Lak!’ says she; there is no water. ‘Lyk!’ says she; there is no meat. The scaldhead with his knife took a little flesh from his leg. He gave it to her; and she refused it. She did not eat it. She brought him out to the surface of the earth.

“The mother of the chicks said to the scaldhead: ‘Just rise up and walk!’ That scaldhead said: ‘Out upon you: can I walk?’ She said: ‘Just walk!’ He rose up to walk. He is lame. The mother of the chicks saw he was lame. She brought out the flesh from underneath her tongue. She put it on the wound and licked it. ‘Just rise up and walk!’ she said. He rose up; he walked.”

Cf with the above, “Asphurtzela,” in M. Wardrop’s Georgian Folk Tales, p. 82, and see the notes by W. R. Halliday on pp. 274-275 of Dawkins’ work mentioned above.

Very similar stories are found in Siberia. Thus in a Kirghiz (N.E. of the Caspian) tale the huge bird Karakus is fed by flesh from the hero’s thigh, and in an Ostyak (N.W. Siberia) story the Fiery-bird consumes both calves of its rider. See C. F. Coxwell, Siberian and Other Folk-Tales, London, 1925, pp. 366, 53 1.—n.m.p.

[31]:

See note at end of chapter.— n.m.p.

[32]:

See Vol. I, pp. 87, 88.

[33]:

A series of elaborate puns.

[34]:

The significance of these names will appear further on.

[35]:

The word may mean “man of romantic anecdote.”