History of Indian Medicine (and Ayurveda)

by Shree Gulabkunverba Ayurvedic Society | 1949 | 162,724 words | ISBN-13: 9788176370813

The History of Indian medicine and Ayurveda (i.e., the science of life) represents the introductory pages of the Charaka Samhita composed of six large sections dealing with every facet of Medicine in ancient India in a Socio-Historical context. Caraka is regarded as one of the pioneers in the field of scientific healthcare. As an important final a...

Chapter 9 - The Students Life and Discipline

As we have already noted, the student lived in the closest association with the teacher. The seclusion of the forest colonies in which these educational institutions were situated did not allow of the distractions that a life in a civic area like that of a town or city that forms the back-ground of the modern institution, would involve. On the other hand their power of observation was greatly enhanced by the nature of their surroundings which were full of life and seasonal changes

1. Student’s Daily Routine

[Carakasaṃhitā Vimānasthāna 8.7]

“Now the method of study is this.—The student who is healthy and hag consecrated all his time for study, should rise at dawn or while yet a portion of the night is left, and having performed the necessary ablutions and having saluted the gods, the seers, the cows, the Brahmanas, the guardians, the elders, the adepts and the teachers, and seating himself at ease on even and clean ground, should, concentrating his mind, go over the aphorisms in order, repeating them over and over again, all the while understanding their import fully, in order to correct his own faults of reading and to recognise the measure of those in the reading of others. In this manner, at noon, in the afternoon and in the night, ever vigilant the student should apply himself to study. This is the method of study”.

[Suśrutasaṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 3.55]

“He must be given to cleanliness, devoted to the preceptor, skilful and free from torpor or excessive sleep”.

[Aṣṭāṅgahṛdayasaṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 2.6]

“He must go to bed after his master has lain down to sleep and must rise from bed before his master”

2. His Dress, Diet. And General Behaviour

[Carakasaṃhitā Vimānasthāna 8.13]

“Thou shalt lead the life of a bachelor, grow thy hair and beard, speak only the truth, eat no meat, eat only pure articles of food, be free from envy and carry no arms”.

[Suśrutasaṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 3.6]

“He must keep his nails and hair clipped close, observe cleanliness, wear brown garments, devote himself to the vow of truth and celibacy and be ever prompt in making obeisance to his elders”

[Suśrutasaṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 3.64]

“Beloved one! As regards the method of study, listen as I describe it. The preceptor should impart instruction to the best of his ability, to the disciple who has approached him in a state of cleanliness wearing his upper garment and with an attentive mind at the appointed hour of instruction”.

[Aṣṭāṅgasaṃgraha Sūtrasthāna 2?]

“Being attired modestly and also differently from the preceptor, the disciple should serve the preceptor as he would a king”.

[Kāśyapasaṃhitā Vimānasthāna 6?]

“He should renounce ridicule, enmity, intoxicating drinks, meats and women.”

[Aṣṭāṅgasaṃgraha Sūtrasthāna 2.7]

“He should not call only by name or should amuse with things though good.”

(“He should not imitate even in ridicule a bad act done by the preceptor”)

3. His Moral. And Religious Life

[Carakasaṃhitā Vimānasthāna 8.13]

“Thou shalt be truthful and free from envy. Thou shalt behave and act without arrogance and with care and attention and with undistracted mind, humility, constant reflection, and with ungrudging obedience.”

[Suśrutasaṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 2.6]

“The disciple should serve his master renouncing evil desire, greed, passion, pride, conceit, envy, harshness, slander, falsehood, indolence and other qualities which bring infamy upon oneself.”

[Kāśypasaṃhitā Vimānasthāna]

“The disciple should be righteous, self-controlled and free from greed, anger, passion, envy and ridicule etc.”

4. Method Of Study

[Suśrutasaṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 3.54]

“One should learn to recite word by word or verse by verse. Again they should be linked together properly as words, phrases and verses. Having thus formulated them, they should be repeatedly recited. One should recite neither too fast nor in a hesitant manner nor in a nasal twang but should recite bringing out each syllable distinctly without over-stressing the accents and without making any distortions of the eye-brows, lips and hands. One must recite systematically and in a voice not too high-pitched nor too low.”

[Carakasaṃhitā Vimānasthāna 8.7]

“The student should prosecute his studies seating himself at ease on even and clean ground and concentrating his mind, should go over the aphorisms in order, repeating them over and over again, all the while understanding their import fully, in order to correct his own faults of reading and to recognise the measure of those in the reading of others. In this manner, at noon, in the afternoon and in the night, ever vigilant the student should apply himself to study. This is is the method of study.”

5. Relation Between. The Guru. And. The Disciple

[Carakasaṃhitā Vimānasthāna 8]

“There shall be nothing that thou outhtest not do at my behest.

Thou shalt dedicate thyself to me and regard me as thy chief. Thou shalt be subject to me and conduct thyself for ever for my welfare and pleasure.”

[Suśrutasaṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 2.6]

“Thou shalt stay, move about, lay thyself down, be seated take thy meals and prosecute thy studies wholly at my bidding”.

[Kāśyapasaṃhitā Vimānasthāna]

“Thou shalt not go without my permission, nor without honouring thy master, nor without finishing your studies”.

[Carakasaṃhitā Vimānasthāna 8.5]

“Approaching such a teacher with a view to winning his favour, one should wait on him vigilantly as on the sacrificial fire, as on a god, as on the king, as on the father and as on one’s own patron”.

Moreover the teacher addresses the pupil as (Vatsa, Kaumya [?]) etc., and the pupil in turn calls the Guru ‘Bhagavan’ (Bhagavān) Thus adjectives used for the teacher and the pupil in the texts are quite significant of the mutual relation of love and respect.

6. Classes

[Carakasaṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna 14.3]

“Agnivesha questioned the tranquil sage Punarvasu who was seated at ease after having finished his prayers, concerning the entire subject of piles.”

[Carakasaṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna 3.3]

“Agnivesha with folded hands, asked Punarvasu, the conqueror of passions, seated peacefully in solitude, the question concerning fever.”

[Carakasaṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 13.3]

“Unto Punarvasu seated in the company of the numerical metaphysicians who had counted all the existing categories of truth, Agnivesha put his question having in his view the world’s welfare”

[Carakasaṃhitā Vimānasthāna 3.3]

“The worshipful Punarvasu Atreya while on a peripatetic tour during the latter month of the hot season, attended by his entourage of disciples, through the woodlands skirting the Ganges near the capital city of Kampilya in the populous zone of the country of Pancala, wherein resided the elite of the twice-born communities, thus observed addressing the disciple Agnivesha.”

[Carakasaṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna 4.3]

“To Punarvasu, who was sojourning in the country of the five rivers and who was self-possessed of mind”

[Carakasaṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna 19.3]

“Having approached obediently, and after making salutations to the worshipful Atreya as he was seated in the northern region of the Himalayas surrounded by an assembly of sages after he had concluded his daily austerities and tended the sacred fire, Agnivesha addressed him.”

A class consisted of at best of six, eight or twelve pupils with one of them as a monitor, acting as a representative of the class with the master and as the deputy of the master with the pupils. He was generally the best pupil of the class. Such, for instance, were Agnivesha and Sushruta in their classes of about six or more.

[Carakasaṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 1.30-31]

“Thereafter Punarvasu, the most benevolent, moved by compassion for all creatures bestowed the science of life on his six disciples—Agnivesha, Bhela, Jatukarna, Parashara, Harita and Ksarapani received the teaching of that sage”.

[Suśrutasaṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 1.3]

“Thus the disciples, Aupadhenava, Vaitarana, Aurabhra, Pauskalavata, Karavirya, Gopuraraksita, Sushruta and others approached and said to the worshipful Dhanvantari, the king of Kasi known as Divodasa, the best among the gods as he was seated in his hermitage surrounded by the sages.”

Commentary—

“The word (prabhṛtaya) means Bhoja and others, but some are of the opinion that Gopura and Rakshita are two persons and thus Aupadhenava followed by the pupils upto Sushruta makes the number eight, ‘and others’ means Nimi, Kankayana, Gargya and Galava, and hence the number of pupils goes to be twelve.”

[Carakasaṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 22.3]

“Addressing himself to the six choicest of his disciples headed by Agnivesha, who were dedicated to study and meditation, the master Atreya declared as follows, with a view to stimulate inquiry”.

[Suśrutasaṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 1.12]

“They said to the worshipful master again, Sushruta being appraised by our common disposition will inquire of your honour on our behalf and whatever is said to him by way of instruction we shall pay due attention to”.

7. Manner and Time of Approach to the Preceptor

[Carakasaṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna 19.3]

“Having approached obediently, the worshipful Atreya as he was seated in the northern region of the Himalayas surrounded by an assembly of sages after he had concluded his daily austerities and tended the sacrifical fire.”

[Carakasaṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna 14.3]

“The sage who was seated at ease after having finished his prayers and was intent upon teaching at the appointed time”

[Carakasaṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna 27.4]

“Agnivesha, choosing the right moment inquired as follows”—

[Carakasaṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna 29.3]

“Agnivesha addressed the master who was seated in an attentive mood and glowing like fire”.

[Carakasaṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna 4.3]

“Saluting the sage who was undeluded of mind and who was resplendent like fire, Agnivesha said (to him)”.

[Carakasaṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna 19.3]

“Agnivesha, having approached obediently and after making salutations, said.”

[Carakasaṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna 21.5]

“Agnivesha choosing the right moment told this to the preceptor very humbly”.

[Carakasaṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna 29.3]

“Agnivesha addressed the master Punarvasu, who was seated in an attentive mood amidst the sages, glowing like fire after completing his daily sacrificial rites.”

[Carakasaṃhitā Vimānasthāna 7.8]

“Agnivesha, touching the feet of the worshipful Atreya, here, asked concerning the characteristics of all kinds of parasites infecting the human body, their cause, habitat, form, color, name, effects and treatment”.

[Carakasaṃhitā Siddhisthāna 3.3]

“Agnivesha with folded hands asked Punarvasu who was surrounded by sages”.

It is evident from the circumstance described in Caraka that the first consideration was paid to cleanliness and purity of body and mind, on the side of both the Master and the pupils. The pupil approaches his master and beseeches instructions on the various aspects of the science only after the Guri has finished his ablutions and religious rites such as feeding the sacrificial fire etc. The Guru is also observed to be sitting amidst brother sages and men of learning. And in certain discussions the pupils as well as the sages present, participate and give out their opinions until in the end, the master surveys the whole range of the subject in its various aspects and gives his final verdict on the subject under discussion.

Thus in Caraka on the subject of the Category of Taste (Sūtrasthāna 26) we find various theories propounded first by those present and the summing up and the final decision declared by the master at the end. Thus the matter was not one-sided and monotonous lecturing by the teacher, oblivious to the various requirements of the varied mental grades of intelligence of the students composing the class. There was a cooperative effort, an intelligent participation by the pupil in the evolution of the final and correct appraisement of a subject and in the formulation of right decisions on mooted points. It follows that the pupils were diligently observing physical and mental cleanliness and purity themselves They performed their baths and prayers with the greatest scruple and kept their minds free from distracting thoughts and emotions They held their master in great reverence and listened to every word dropping from his mouth with respectful and intelligent attention, and yet never hesitated to state their position in case of doubt and ask for further clarification and light. The student whenever he approached the master prostrated at his feet. One of the main qualities required was that the disciple should be (abhivādanaśīla) one offering respectful salutation to the master. He must be obedient and modest. He must have self-restraint and must fold his hands before his master. He must not be arrogant or boastful and must deport himself with modesty and self-effacement. He must be given to simplicity both in dress and manner. Certainly the attitude of mind that such conduct required was one of the great and sincere thirst for knowledge and an unfailing faith in the wisdom and virtue of the master at whose feet he learnt his lessons

This is a spirit that dominated in the ancient method of education.

A religious and ardent attitude without yet forsaking the democratic spirit greatly added to the advantage that the pupil derived from his teacher. In education, the spirit of approach is everything. The reverence that characterised the pupil at that period induced him to pay intelligent and respectful attention to every word of the master.

The monotony of the lecturing will bore many a student m the educational institutions. In ancient India this boredom was avoided by the question and answer method known as or discoursive method. The scriptures also lay down that an aspirant to knowledge should hear by obedience by questioning or by service (tadviddhi praṇipātena paripraśnena sevayā).

In a class it was the monitor known as the foremost pupil that put respectfully questions with a view to the edification of the class as well as the world in general. This was also the method obtaining in ancient Greece known as the Socratic method, now seen in the dialogues of Plato.

The physical appearance of the pupils was in keeping with the spirit of their mental and moral outlook. The Brahmacari was required to grow his beard and hair and wear brown garment. He must be diligent in the observance of cleanliness and clip his nails and hair. Thus a Brahmacari must have been easily recognisable from his dress and bearing. The idea of a uniform for students must therefore have been in vogue even in those days.

In his daily conduct he was required to observe strict rules. His obedience and submission to the Guru were expressed in his behaviour towards him. He must make respectful salutations to him and seat himself before his Guru occupying a lower position and at some distance. In his diet he has to eschew meat and intoxicating drinks. He must avoid all kinds of luxuries and the company of women. He must not bear arms nor commit criminal offences. He must not be an absolute ignoramus as regards the things of the world ether. He was required to know how to adjust to the needs of time and place (deśakālajña). He should avoid excess of sleep and indolence and be alert and active in his habits. Thus the life of a Brahmacari was no easy one, but a disciplined life of cleanliness and purity illuminated by a dominant love of knowledge and service

The course of medical education ran through a period of 7 years and during that period he was styled Brahmacari (Brahmacārī). After completing this education the student who is known as “Adhyayanantaga” (adhyayanāntaga [adhyayanāntagaḥ]) takes his leave to enter into the next stage of life known as “Grihastha” (gṛhastha) i.e., the married life. He may pay as a token of gratitude, to his teacher his fee before departing and he undergoes a ceremony akin to modern convocation ceremony. He is then called a “Snataka” (snātaka) meaning baptised. He is then a real Dvija or according to some a Trija, a twice born or thrice-born.

There was a class of Brahmacari who continued to pursue their studies further all through their lives and took a vow to that effect. They were known as Naisthika Brahmacaris (Naiṣṭhika Brahmacārin) or life-long scholars who dedicated their whole lives to the pursuit of knowledge.

There were some as in all times, who were of unsteady mind, who went about from teacher to teacher, from one institution to another and never stuck up to any place or person long enough to be of any profit to themselves or others Such fickle students were known as “Tirtha-Kakas’ (tīrthakāka) meaning “wandering crows”.

Every institution was a residential one, which assured close contact between the master and the pupils and engendered a spirit of mutual understanding, accommodation and love among the young students. They accompanied the master on his sojourns to neighbouring places either for purposes of practical study and demonstration or for discussions and conferences with other sages and institutions Again after the course of studentship the young men invariably visited either by way of pilgrimage or prompted by a desire to see the broad world, the places of religious and cultural centres. Thus their mental vision was broadened and a universal and humanistic outlook inspired their every thought and action.

The main ideal of the instruction was to develop a full man in the student. For that, hard life was prescribed and it was keenly observed that the student became more and more self-reliant. Great attention was paid to the preservation of cleanliness of the mind and body. All this comprised the physical and ethical side and no pain was spared to develop the intellectual side too. With this purpose in view, debates on scientific subjects were often held to develop and test the power of reasoning Impetus was given to the spirit of inquiry and research and the student was helped to abandon bigotry and to cultivate broadness of vision. Thus moral and spiritual progress paved the way to the building of character and the real ideal of education was realized

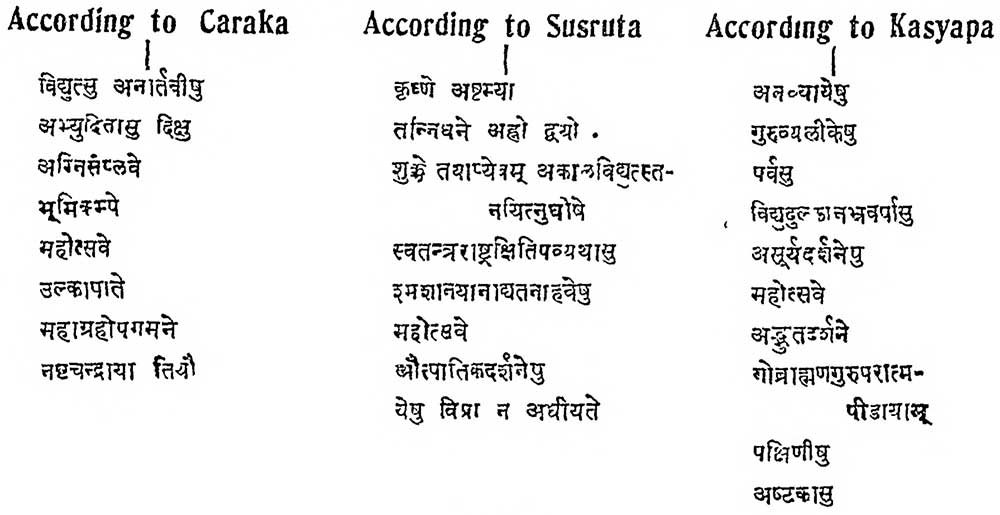

8. Holidays

Lastly, we shall note that certain days were observed as holidays, when the students were to abstain from study. There was a general injunction advising a student not to resort to study while in hunger or thirst or disease or indisposition.

[Kāśyapasaṃhitā]

“One should not study when he is overpowered by hunger, thirst, disease, dejection etc.”

[Carakasaṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 8.24]

“Do not conduct your studies, during unseasonal lightning, when the quarters are lit up with a lurid glow or while a conflagration is in progress, during an earthquake, at festive-tide at, the time of meteoric showers, during eclipses of the sun and moon, on the new moon day and during the two twilights.”

[Suśrutasaṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 2.9-10]

“Do not conduct your studies on the eighth day of the darkhalf, the last two days of the fortnight, and the same days of the bright half, two twilights of the day, on days of unseasonal lightning and thunder of clouds, on occasions of calamity to the sovereign or to the sovereignty of the realm, on going to cremation ground or in times of war, on great festival days or on sight of any unnatural phenomena”.

[Kāśyapasaṃhitā Vimānasthāna Pṛ. 40]

“Do not study on holy days, at two twilights, on days of lightning and tempest, on cloudy and rainy days on days when the sun is not sighted, on great festival-days, immediately after taking meals, on sight of any thing marvellous, on days when the master is uneasy or when there occurs some distress to the cows, the Brahmanas, the preceptor or such others, on the day of the full-moon and on the eighth day of each fortnight.”

Whenever there was inclement weather such as lightning, thunder-storms, when the sun was hidden by clouds, when there was earthquake, when thunderbolts fell, when there was an eclipse of the sun or the moon or on the new-moon day and at the time of the two twilights—at these times the students should avoid their studies Besides these prohibited times, the great days of national and religious festivities such as the new years day and the birthdays of divine incarnations, must necessarily have been observed. We give below a detailed list of the general holidays observed according to the three ancient classics of Caraka, Sushruta and Kashyapa.