Egypt Through The Stereoscope

A Journey Through The Land Of The Pharaohs

by James Henry Breasted | 1908 | 103,705 words

Examines how stereographs were used as a means of virtual travel. Focuses on James Henry Breasted's "Egypt through the Stereoscope" (1905, 1908). Provides context for resources in the Travelers in the Middle East Archive (TIMEA). Part 3 of a 4 part course called "History through the Stereoscope."...

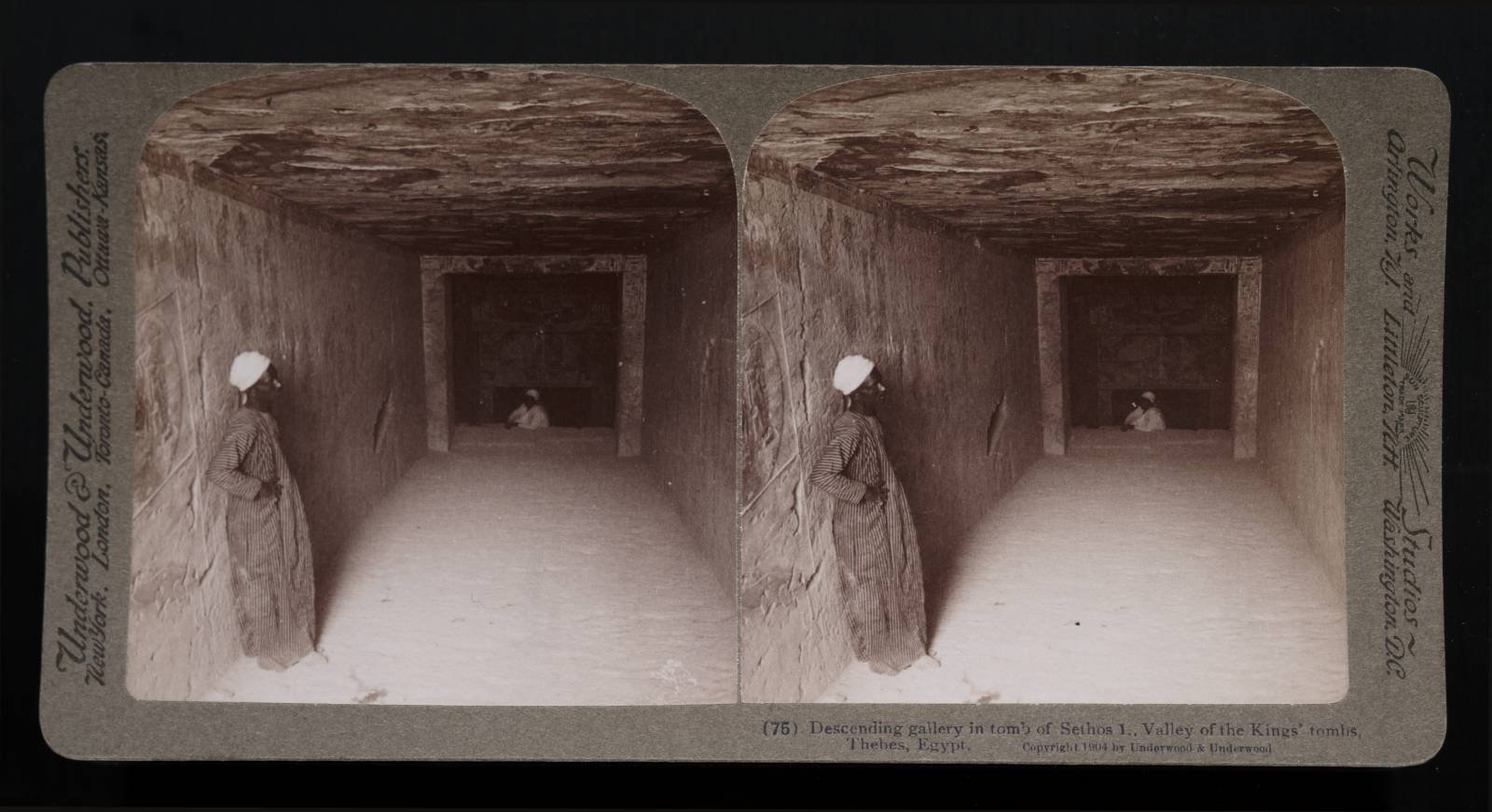

Position 75 - Descending Gallery In The Tomb Of Sethos I, Valley Of The Kings' Tombs, Thebes

How different from the tomb chambers which we have seen before! Yes, but this gallery is not a tomb chapel, nor are any of the halls to which it leads. The rock tombs, which we have thus far seen, are all chapels, where the dead lived and received his food, drink and clothing.

How different from the tomb chambers which we have seen before! Yes, but this gallery is not a tomb chapel, nor are any of the halls to which it leads. The rock tombs, which we have thus far seen, are all chapels, where the dead lived and received his food, drink and clothing.

King Sethos I's chapel is not here, but we shall see it later, on the western plain, where we found the Ramesseum and the colossi marking the chapel of Amenophis III. All those temples out there on the western plain were the mortuary chapels of the kings; this excavation in the mountain is only the sepulchral chamber for the mummy, and the long corridor leading in from the face of the cliff to that chamber.

But this place of deposit for the mummy has developed far beyond the simple descending passage which served the purpose in the pyramid. It has now become a long gallery descending into the mountain through hall after hall, until that one is reached in which the mummy was laid. This gallery before us goes down through the successive halls 330 feet into the mountain. At the end, in the last chamber, was a vast stone sarcophagus, in which the king was interred.

The sarcophagus in this tomb, a magnificent work cut from one block of alabaster, is now in Sir John Soane's museum in London; and the body of King Sethos I, which was here interred in it, you have already seen in the Cairo Museum (Position 12). All about us on the door-posts and lintels is the name of Sethos I, and the walls are covered with inscriptions describing the career of the dead in the hereafter, and furnishing him with the magical formularies which shall deliver him from the hideous and grotesque monsters that beset his path as he leaves this world.

Many of these monsters are depicted by the artists on the walls of the galleries and chambers. To enable the tourists to see these things without the use of smoky torches, which damage the colors, the government has put in electric lights, and you can see the wire leading along the ceiling of this gallery.

Here, we stand immediately within the entrance, which is just behind us. It is like the entrance to tomb No. 9, which we saw from the top of the cliff. A flight of steps behind us leads down to the descending gallery in which we are, and another similar flight at the lower end where that native sits, conducts to a second descending gallery exactly like this one, below which, after a small ante-chamber, the first hall is found. There were elaborate devices for concealing the entrance and for misleading the tomb robbers when they had once discovered the entrance. Nevertheless, these tombs have all been rifled in remote antiquity, and already at the end of the 18th Dynasty, about 1350 B. C., it was found difficult to protect them.

By the time of the last Ramessids, at the close of the 20th Dynasty (about 1100 B. C.), the robberies were common, and we have the court records of the prosecution of certain tomb robbers under Ramses IX, now preserved in the British Museum. Finally the priest-king's of the 21st Dynasty, unable to protect the bodies of their great ancestors, were forced to bring them together in a place of concealment, where they lay until modern times.

Let us now return to one of our former standpoints at the Ramesseum, from which we can see the place where the royal mummies were hidden.