Egypt Through The Stereoscope

A Journey Through The Land Of The Pharaohs

by James Henry Breasted | 1908 | 103,705 words

Examines how stereographs were used as a means of virtual travel. Focuses on James Henry Breasted's "Egypt through the Stereoscope" (1905, 1908). Provides context for resources in the Travelers in the Middle East Archive (TIMEA). Part 3 of a 4 part course called "History through the Stereoscope."...

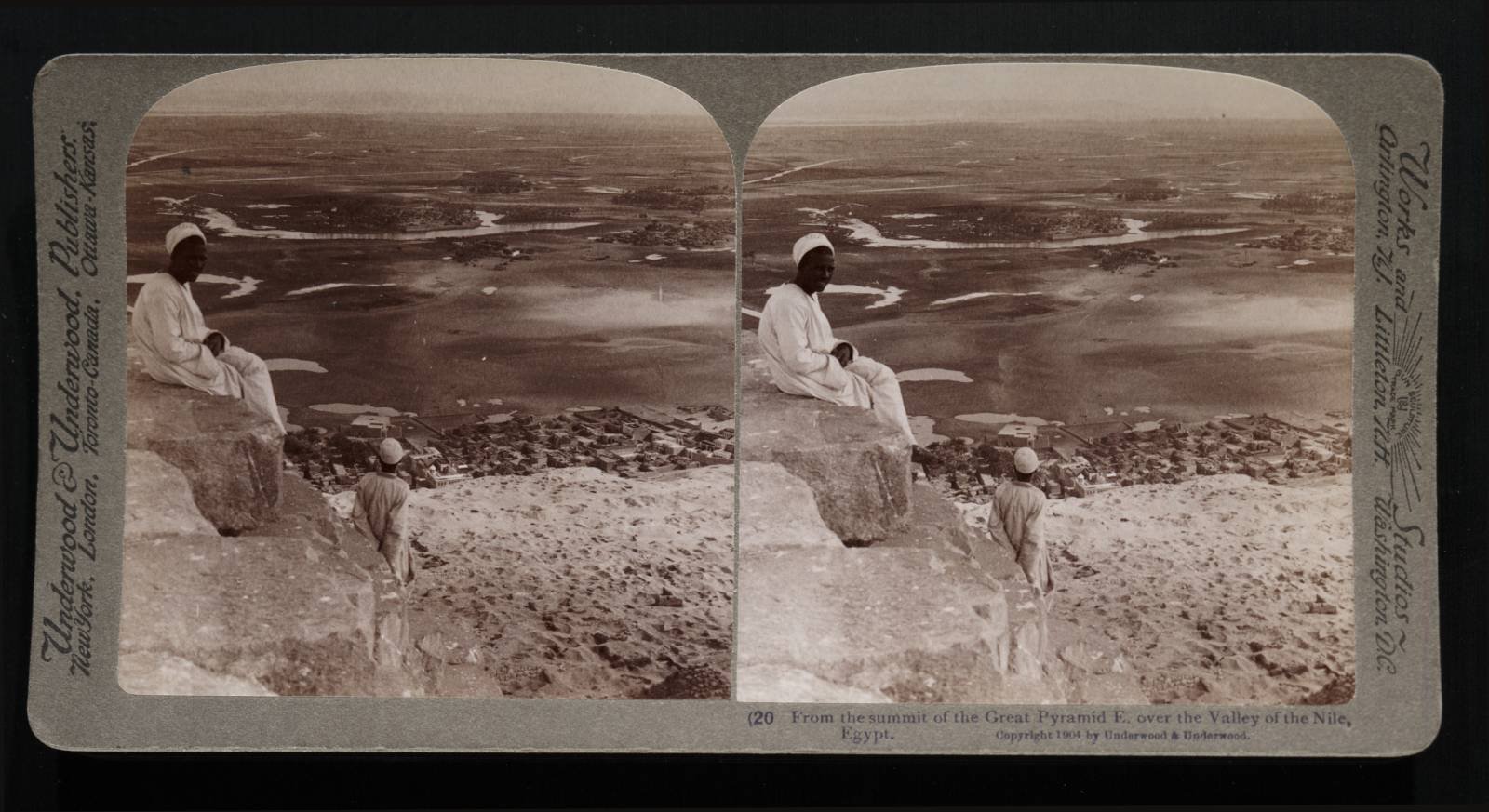

Position 20 - View From The Summit Of The Great Pyramid, East Over The Valley Of The Nile

At last we are here! And the first thought is doubt and questioning. Is it possible that we stand at last upon the summit of the venerable monument of which we have so long dreamed? But look out there upon this fertile valley, green and smiling under the brightest of blue skies; then drop your eyes upon this dead stretch of sand at our feet. Nowhere but upon the summit of this great pyramid is there such a prospect of the most prodigal and unlimited wealth of life, to be viewed from the very heart of death. Before us, as far as the eye can penetrate and distinguish, there is this wide expanse of fertile bottom, teeming with the thousand elements of life; while behind us and on either hand are the silence and death of the desert.

At last we are here! And the first thought is doubt and questioning. Is it possible that we stand at last upon the summit of the venerable monument of which we have so long dreamed? But look out there upon this fertile valley, green and smiling under the brightest of blue skies; then drop your eyes upon this dead stretch of sand at our feet. Nowhere but upon the summit of this great pyramid is there such a prospect of the most prodigal and unlimited wealth of life, to be viewed from the very heart of death. Before us, as far as the eye can penetrate and distinguish, there is this wide expanse of fertile bottom, teeming with the thousand elements of life; while behind us and on either hand are the silence and death of the desert.

What a land of contrasts!—contrasts between the ancient and modern condition of the nation; contrasts between natural conditions side by side. You stand out there almost anywhere, with one foot in the desert sands and the other buried in verdure. I have a photograph taken there, of a donkey standing with forelegs in the grass, and with hind legs in the desert.

We are looking just a little south of eastward, directly across the Nile valley, here above the southern apex of the Delta. The Delta, therefore, stretches away northward and northeastward on our left (out of our range of vision at present) till it meets the Mediterranean; and over on the horizon line are the cliffs which mark the other side, the east side of the valley. They rise to the Arabian desert, which extends in rolling desolate hills to the Red Sea beyond. Just out of range on our left, at the foot of those distant cliffs, is Cairo (see the red lines numbered 20 on Map 4), behind which we stood and looked over to these pyramids.

Leading to the city, but also out of our field at the moment, is the road shaded with its long double line of lebbek trees, along which we came out here from Cairo. On our right the margin of the desert winds southward in a sinuous line, as you see it beginning just at our feet by the side of that town, till it passes Memphis eleven miles south of us. Behind us the Sahara in a waste of billowy hills rolls on to the Atlantic two thousand miles away. It is our first clear and unobstructed view of the valley from cliff to cliff, and you will find it profitable to stop here and ponder long and well our exact location and its relation with other important and main points.

Out there barely visible upon the skyline we have already noted the cliffs on the eastern side of the Nile; the river itself is that broad white line just under the horizon coming into view at about the middle of our present prospect and running out of range at the left. It is the river and those cliffs yonder which made possible the great pyramid. For the cliffs furnished a limestone of the finest quality and the river at high water made its transportation possible to the very foot of the bluff below us, where a huge causeway led up here to the pyramid, directly through the ground where this village now stands.

Up the causeway, of which large remains are still surviving, the stone was dragged to the desert plateau. The village now built over the causeway is Kafr, which you will remember, we saw from the road to the pyramids, in our first view of them (Position 16). Later we shall visit those distant quarries and see the vast halls and galleries, from which the great pyramid was taken.

The annual inundation which floated the heavy barges, laden with the massive blocks, has, as you see here, fallen, and left pools and patches of water here and there. Everywhere the retreating waters have left a deposit of rich mud from the highlands of Abyssinia, which in large measure explains the marvelous productivity of these fields.

The rise of the waters is already observable in June at the first cataract, though not here in Lower Egypt . By the first of August it is considerable, but the increase continues to the latter half of September, when, after maintaining a constant level for twenty or thirty days, the waters again rise, till by the middle of October they have reached the maximum level. At this time, the whole country before us may be flooded; for example, in the autumn of 1894, I saw this district, especially looking northward and northeastward from our present station, so flooded that it looked like a vast inland sea.

Its glistening surface was flecked here and there with palm groves, marking the villages; but these, like Kum el-Aswad yonder, although surrounded by water, are upon higher ground. Ordinarily they are beyond the reach of the water, but in 1894, thousands of natives were driven from their homes by the flood and forced to seek refuge on the neighboring highlands, till the subsidence began. This is already in full course by December; the fields now gradually dry up, as you see them doing at our feet, the pools disappear and the peasant is dependent for irrigation upon the waters stored in reservoirs kept in repair for the purpose, and the vast network of canals, which ramify throughout the country, like a life-giving arterial system.

The government supervision of this system is necessarily close and effective, as it was in ancient Egypt. At the second cataract are rock inscriptions of the 12th Dynasty (19th century B. C.), marking the maximum height of the flood, in order that comparison might be made from year to year and the water properly distributed and used. At present the vertical rise of the waters from lowest to highest is usually about 49 feet at the first cataract, at Thebes it is 38 feet, while here at Cairo it is about 25 feet and in the Delta still less.

The husbanding of these waters began in prehistoric times; and by 2000 B. C. vast government works were constructed for storing them for future use, as we shall see when we have visited the Fayum. In modern times, after much mediaeval neglect by the Moslems, a huge dam has been built at the southern apex of the Delta, usually known as the “barrage.” The English have recently built another at Assiut, and still another at the first cataract, the last being the largest dam in the world.

Indeed the English are at present developing these resources of the Nile inundation with unprecedented success, though not without disregard of the nation's inheritance in its ancient monuments, as we shall see, when we have reached Philae. But when we remember that the only rain which the country can receive is from those rare cyclonic storms, which force rain-bearing clouds from the Mediterranean southeastward across the Sahara into the Nile valley, we shall understand the necessity for utilizing the life-giving Nile to the utmost.

I have met children in Upper Egypt, fifteen years of age, who have never seen a heavy rain; at the same time, slight showers have been known to fall at Thebes, several years in succession, and Petrie's mud-brick excavators' quarters were one season almost washed down by a forty-eight-hour rain. When we have begun our trip up the river, we shall see how the natives employ the waters, which are thus husbanded for them by the government.

Let us now turn about, toward our right, nearly if not quite one-third of a complete circle. This present prospect will then be behind us and on our left; while the second pyramid, now behind us on our right, will be directly before us. Find the red lines numbered 21 on Map 5.