Egypt Through The Stereoscope

A Journey Through The Land Of The Pharaohs

by James Henry Breasted | 1908 | 103,705 words

Examines how stereographs were used as a means of virtual travel. Focuses on James Henry Breasted's "Egypt through the Stereoscope" (1905, 1908). Provides context for resources in the Travelers in the Middle East Archive (TIMEA). Part 3 of a 4 part course called "History through the Stereoscope."...

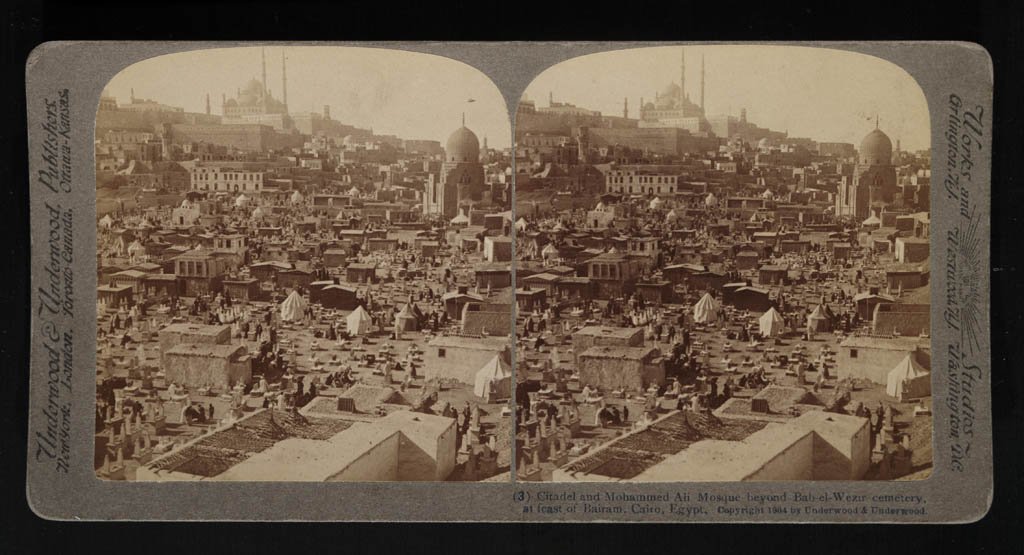

Position 3 - Citadel And Mohammed Ali Mosque, Beyond The Bab El-wezir Cemetery, at The Feast Of Bairam, Cairo

We have now descended from the citadel, you see, and, having taken up our position on the north of it, are looking southward toward it. On our right, but not included in our field of vision, is the city itself; on our left is the eastern desert, while behind us is the eastern half of the Delta. The city of which we see the eastern edge on our right, did not originally include the citadel before us, but where those massive walls now rise were the bare rocks of the eastern cliffs that bound the valley on this

We have now descended from the citadel, you see, and, having taken up our position on the north of it, are looking southward toward it. On our right, but not included in our field of vision, is the city itself; on our left is the eastern desert, while behind us is the eastern half of the Delta. The city of which we see the eastern edge on our right, did not originally include the citadel before us, but where those massive walls now rise were the bare rocks of the eastern cliffs that bound the valley on this  side. But when the great Saladin, the conqueror of the Crusaders, came to the city, with his fine military judgment he saw the necessity of a stronghold commanding the place, and preventing a besieging enemy from doing the same.

side. But when the great Saladin, the conqueror of the Crusaders, came to the city, with his fine military judgment he saw the necessity of a stronghold commanding the place, and preventing a besieging enemy from doing the same.

In 1176 he therefore began masonry fortifications up yonder on the height now crowned by that tall mosque, and planned a great wall around the city below, which latter was never entirely finished. He employed on the work hosts of European captives, whom he took from the ranks of the Crusaders. Little of the old walls of the crusading days now remains, for the citadel has often been enlarged, remodeled and strengthened since Saladin's time.

The place where we stood overlooking the city is just on the right of the short, thick tower on the right of the two tall minarets, but further back, in a line directly away from us. Our line of sight there was across that along which we look at present, and, of course, directed toward our right as we now stand. The white buildings behind the parapets of the fort on the extreme left are the barracks of the present garrison. The great mosque which surmounts the citadel with its tall and graceful minarets, is the most prominent landmark in Cairo. It was begun by the founder of the reigning dynasty of viceroys in Egypt, Mohammed Ali, after the blowing up of an old palace, which occupied the same place in 1824. His architects, as the building shows, were Turks. It was not completed until 1857 under Said Pacha, after the death of Mohammed Ali, which occurred in 1849. The great rejuvenator of Egypt is buried in a splendid tomb under one corner of the large dome.

The citadel marks the rise of a new and vigorous dynasty, and also the beginning of a new day for Egypt. The long domination of the Mamlukes, which for 600 years had cursed this fair land, was brought to a bloody end on yonder heights, when in 1811 on the 1st of March, they were craftily assembled in the narrow, high-walled approach to the citadel, which you see coming up from the town on the right (the Bab el-Azab in the Place Rumêlah, seen from Position 2), and there by order of Mohammed Ali, they were shot down from the surrounding walls without mercy. Of the 480, only one, Amin Bey, escaped by leaping his horse down through a gap in the crenellated wall to the moat below, whence he succeeded in making his way to the desert. The guides and dragomans of Cairo will show you a place some 90 feet high, up yonder on the right, which they affirm with the utmost gravity is the spot from which Amin Bey leaped his horse.

Nearer us is an animated scene characteristic of modern Cairo, in the Cemetery of the Bab el-Wezir or Gate of the Vizier from which the cemetery is named. It is there in the right-hand corner of the cemetery, behind the large-domed tomb of Tarabai esh-Sherif on the right. The city wall does not enclose the cemetery, but you will see some of its angles there on the right of the tomb of Tarabai, with the large dome, after passing which the wall turns to the left, beyond the last tent at the other end of the cemetery; and you can see it extended eastward before the citadel, just in front of the heavy tower that rises below the citadel wall on the left. At that point there is another gate, and the streets from both gates pass along in front of the citadel below the spot where we overlooked the city for the first time.

You are, without doubt, wondering at these tents and houses in the cemetery. The townspeople are celebrating what they call the “Lesser Feast,” a very interesting festival, which occurs after the fast of Ramadan. The occasion of the rejoicing evident here is very natural. These poor people have been fulfilling the most rigorous obligation imposed by the Mohammedan religion; that is, in the celebration of the fast of Ramadan, every orthodox Moslem is forbidden, during the time between sunrise and sunset for the entire month, to touch food. Naturally when this severe requirement has been duly complied with, they are quite ready to celebrate its termination. The first three days of the following month, called Shawwal, are therefore devoted to feasting, rejoicing and congratulations. The celebration often goes by its Turkish name, “Bairam.”

However incongruous it may seem, you see that these good people have chosen the cemetery as the place in which to celebrate their feast; this is commonly done at this time. Some of them have permanent dwellings here, which they temporarily occupy at the time of this feast. These are the houses which you see scattered through the cemetery; they are erected over the tombs of the departed members of the family. Others who have no such dwelling erect a tent over the tomb. On at least one of the three days of the celebration, they come to the cemetery laden with palm branches which they strew upon the tombs. The house just before us shows how such dwellings are arranged. The court covered over with plaited branches contains the tombs of the dead, while the roofed portion is the dwelling in which the relatives stay during the sojourn at the cemetery.

The hum of voices reciting the Koran, the shouts and the gay laughter and the rejoicing of the poor at the gate of the cemetery, as they receive the food distributed by the rich, all this, with the citadel and its splendid mosque outlined against the bluest of skies in the distance, gives the traveler a typical scene of oriental life, as it is found only at Cairo. Behind us at the Bab en-Nasr, which is also on this side of the city, the jubilation and merry-making are even more marked than here, and the temporary booths, with piles of sweets, the merry-go-rounds, the dancers and the rejoicing multitudes give one the impression of a large country fair. In a few days these same people will be following the pieces of the sacred carpet or “kisweh” from the citadel to the Mosque of Hasanên, in a rejoicing procession to which all Cairo will turn out. That procession is one of the most interesting public events at Cairo, and we shall later have the opportunity of observing it.

Meanwhile, we shall turn half round, at the same time moving a short distance northward or to our right, and shall look across the city southwestward. Find on Map 4 the red lines numbered 4, which start from the east side of the city and branch southwestward to the pyramids of Gizeh about ten miles away.