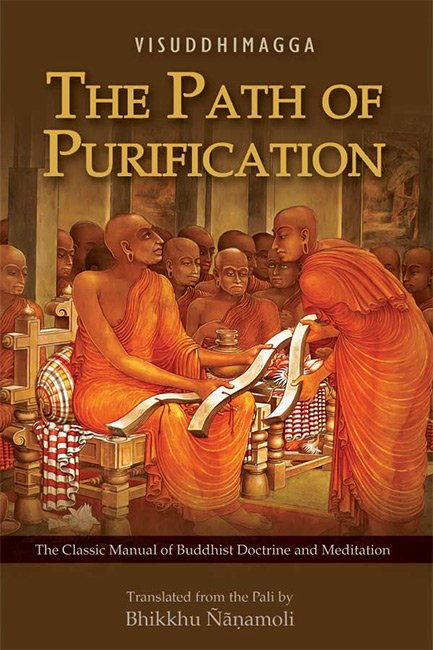

Visuddhimagga (the pah of purification)

by Ñāṇamoli Bhikkhu | 1956 | 388,207 words | ISBN-10: 9552400236 | ISBN-13: 9789552400236

This page describes (8) Mindfulness Occupied with the Body of the section Other Recollections as Meditation Subjects of Part 2 Concentration (Samādhi) of the English translation of the Visuddhimagga (‘the path of purification’) which represents a detailled Buddhist meditation manual, covering all the essential teachings of Buddha as taught in the Pali Tipitaka. It was compiled Buddhaghosa around the 5th Century.

(8) Mindfulness Occupied with the Body

42. Now comes the description of the development of mindfulness occupied with the body as a meditation subject, which is never promulgated except after an Enlightened One’s arising, and is outside the province of any sectarians. It has been commended by the Blessed One in various ways in different suttas thus: “Bhikkhus, when one thing is developed and repeatedly practiced, it leads to a supreme sense of urgency, to supreme benefit, to supreme surcease of bondage, to supreme mindfulness and full awareness, to acquisition of knowledge and vision, to a happy life here and now, to realization of the fruit of clear vision and deliverance. What is that one thing? It is mindfulness occupied with the body” (A I 43). And thus: “Bhikkhus, they savour the deathless who savour mindfulness occupied with the body; they do not savour the deathless who do not savour mindfulness occupied with the body.[1] [240] They have savoured the deathless who have savoured mindfulness occupied with the body; they have not savoured … They have neglected … they have not neglected … They have missed … they have found the deathless who have found mindfulness occupied with the body” (A I 45). And it has been described in fourteen sections in the passage beginning, “And how developed, bhikkhus, how repeatedly practiced is mindfulness occupied with the body of great fruit, of great benefit? Here, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu, gone to the forest …” (M III 89), that is to say, the sections on breathing, on postures, on the four kinds of full awareness, on attention directed to repulsiveness, on attention directed to elements, and on the nine charnel-ground contemplations.

43. Herein, the three, that is to say, the sections on postures, on the four kinds of full awareness (see M-a I 253f.), and on attention directed to elements, as they are stated [in that sutta], deal with insight. Then the nine sections on the charnelground contemplations, as stated there, deal with that particular phase of insight knowledge called contemplation of danger. And any development of concentration in the bloated, etc., that might be implied there has already been explained in the Description of Foulness (Ch. VI). So there are only the two, that is, the sections on breathing and on directing attention to repulsiveness, that, as stated there, deal with concentration. Of these two, the section on breathing is a separate meditation subject, namely, mindfulness of breathing.

[Text]

44. What is intended here as mindfulness occupied with the body is the thirtytwo aspects. This meditation subject is taught as the direction of attention to repulsiveness thus: “Again, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu reviews this body, up from the soles of the feet and down from the top of the hair and contained in the skin, as full of many kinds of filth thus: In this body there are head hairs, body hairs, nails, teeth, skin, flesh, sinews, bones, bone marrow, kidney, heart, liver, midriff, spleen, lungs, bowels, entrails, gorge, dung, bile, phlegm, pus, blood, sweat, fat, tears, grease, spittle, snot, oil of the joints, and urine” (M III 90), the brain being included in the bone marrow in this version [with a total of only thirty-one aspects].

45. Here is the description of the development introduced by a commentary on the text.

[Word Commentary]

This body: this filthy body constructed out of the four primary elements. Up from the soles of the feet: from the soles of the feet upwards. Down from the top of the hair: from the highest part of the hair downwards. Contained in the skin: terminated all round by the skin. Reviews … as full of many kinds of filth: [241] he sees that this body is packed with the filth of various kinds beginning with head hairs. How? “In this body there are head hairs … urine.”

46. Herein, there are means, there are found. In this: in this, which is expressed thus: “Up from the soles of the feet and down from the top of the hair and contained in the skin, as full of many kinds of filth.” Body: the carcass; for it is the carcass that is called “body” (kāya) because it is a conglomeration of filth, because such vile (kucchita) things as the head hairs, etc., and the hundred diseases beginning with eye disease, have it as their origin (āya).

Head hairs, body hairs: these things beginning with head hairs are the thirty-two aspects. The construction here should be understood in this way: In this body there are head hairs, in this body there are body hairs.

47. No one who searches throughout the whole of this fathom-long carcass, starting upwards from the soles of the feet, starting downwards from the top of the head, and starting from the skin all round, ever finds even the minutest atom at all beautiful in it, such as a pearl, or a gem, or beryl, or aloes,[2] or saffron, or camphor, or talcum powder; on the contrary he finds nothing but the various very malodorous, offensive, drab-looking sorts of filth consisting of the head hairs, body hairs, and the rest. Hence it is said: “In this body there are head hairs, body hairs … urine.”

This is the commentary on the word-construction here.

[Development]

48. Now, a clansman who, as a beginner, wants to develop this meditation subject should go to a good friend of the kind already described (III.61–73) and learn it. And the teacher who expounds it to him should tell him the sevenfold skill in learning and the tenfold skill in giving attention.

[The Seven-fold Skill in Learning]

Herein, the seven-fold skill in learning should be told thus: (1) as verbal recitation, (2) as mental recitation, (3) as to colour, (4) as to shape, (5) as to direction, (6) as to location, (7) as to delimitation.

49. 1. This meditation subject consists in giving attention to repulsiveness. Even if one is master of the Tipiṭaka, the verbal recitation should still be done at the time of first giving it attention. For the meditation subject only becomes evident to some through recitation, as it did to the two elders who learned the meditation subject from the Elder Mahā Deva of the Hill Country (Malaya). On being asked for the meditation subject, it seems, the elder [242] gave the text of the thirty-two aspects, saying, “Do only this recitation for four months.” Although they were familiar respectively with two and three Piṭakas, it was only at the end of four months of recitation of the meditation subject that they became stream-enterers, with right apprehension [of the text]. So the teacher who expounds the meditation subject should tell the pupil to do the recitation verbally first.

50. Now, when he does the recitation, he should divide it up into the “skin pentad,” etc., and do it forwards and backwards. After saying “Head hairs, body hairs, nails, teeth, skin,” he should repeat it backwards, “Skin, teeth, nails, body hairs, head hairs.”

51. Next to that, with the “kidney pentad,” after saying “Flesh, sinews, bones, bone marrow, kidney,” he should repeat it backwards, “Kidney, bone marrow, bones, sinews, flesh; skin, teeth, nails, body hairs, head hairs.”

52. Next, with the “lungs pentad,” after saying “Heart, liver, midriff, spleen, lungs,” he should repeat it backwards, “Lungs, spleen, midriff, liver, heart; kidney, bone marrow, bones, sinews, flesh; skin, teeth, nails, body hairs, head hairs.”

53. Next, with the “brain pentad,” after saying “Bowels, entrails, gorge, dung, brain,” he should repeat it backwards, “Brain, dung, gorge, entrails, bowels; lungs, spleen, midriff, liver, heart; kidney, bone marrow, bones, sinews, flesh; skin, teeth, nails, body hairs, head hairs.”

54. Next, with the “fat sextad,” after saying “Bile, phlegm, pus, blood, sweat, fat,” he should repeat it backwards, “Fat, sweat, blood, pus, phlegm, bile; brain, dung, gorge, entrails, bowels; lungs, spleen, midriff, liver, heart; kidney, bone marrow, bones, sinews, flesh; skin, teeth, nails, body hairs, head hairs.”

55. Next, with the “urine sextad,” after saying “Tears, grease, spittle, snot, oil of the joints, urine,” he should repeat it backwards, “Urine, oil of the joints, snot, spittle, grease, tears; fat, sweat, blood, pus, phlegm, bile; brain, dung, gorge, entrails, bowels; lungs, spleen, midriff, liver, heart; kidney, bone marrow, bones, sinews, flesh; skin, teeth, nails, body hairs, head hairs.” [243]

56. The recitation should be done verbally in this way a hundred times, a thousand times, even a hundred thousand times. For it is through verbal recitation that the meditation subject becomes familiar, and the mind being thus prevented from running here and there, the parts become evident and seem like [the fingers of] a pair of clasped hands,[3] like a row of fence posts.

57. 2. The mental recitation should be done just as it is done verbally. For the verbal recitation is a condition for the mental recitation, and the mental recitation is a condition for the penetration of the characteristic [of foulness].[4]

58. 3. As to colour: the colour of the head hairs, etc., should be defined.

4. As to shape: their shape should be defined too.

5. As to direction: in this body, upwards from the navel is the upward direction, and downwards from it is the downward direction. So the direction should be defined thus: “This part is in this direction.”

6. As to location: the location of this or that part should be defined thus: “This part is established in this location.”

59. 7. As to delimitation: there are two kinds of delimitation, that is, delimitation of the similar and delimitation of the dissimilar. Herein, delimitation of the similar should be understood in this way: “This part is delimited above and below and around by this.” Delimitation of the dissimilar should be understood as non-intermixed-ness in this way: “Head hairs are not body hairs, and body hairs are not head hairs.”

60. When the teacher tells the skill in learning in seven ways thus, he should do so knowing that in certain suttas this meditation subject is expounded from the point of view of repulsiveness and in certain suttas from the point of view of elements. For in the Mahā Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta (DN 22) it is expounded only as repulsiveness. In the Mahā Hatthipadopama Sutta (MN 28), in the Mahā Rāhulovāda Sutta (MN 62), and the Dhātuvibhaṅga (MN 140, also Vibh 82), it is expounded as elements. In the Kāyagatāsati Sutta (MN 119), however, four jhānas are expounded with reference to one to whom it has appeared as a colour [kasiṇa] (see III.107). Herein, it is an insight meditation subject that is expounded as elements and a serenity meditation subject that is expounded as repulsiveness. Consequently it is only the serenity meditation subject [that is relevant] here.

[The Tenfold Skill in Giving Attention]

61. Having thus told the sevenfold skill in learning, he should tell the tenfold skill in giving attention as follows: (1) as to following the order, (2) not too quickly, (3) not too slowly (4) as to warding off distraction, (5) as to surmounting the concept, (6) as to successive leaving, (7) as to absorption, (8)–(10) as to the three suttantas.

62. 1. Herein, as to following the order: from the time of beginning the recitation [244] attention should be given following the serial order without skipping. For just as when someone who has no skill climbs a thirty-two-rung ladder using every other step, his body gets exhausted and he falls without completing the climb, so too, one who gives it attention skipping [parts] becomes exhausted in his mind and does not complete the development since he fails to get the satisfaction that ought to be got with successful development.

63. 2. Also when he gives attention to it following the serial order, he should do so not too quickly. For just as when a man sets out on a three-league journey, even if he has already done the journey out and back a hundred times rapidly without taking note of [turnings] to be taken and avoided, though he may finish his journey, he still has to ask how to get there, so too, when the meditator gives his attention to the meditation subject too quickly, though he may reach the end of the meditation subject, it still does not become clear or bring about any distinction. So he should not give his attention to it too quickly.

64. 3. And as “not too quickly,” so also not too slowly. For just as when a man wants to do a three-league journey in one day, if he loiters on the way among trees, rocks, pools, etc., he does not finish the journey in a day and needs two or three to complete it, so too, if the meditator gives his attention to the meditation subject too slowly, he does not get to the end and it does not become a condition for distinction.

65. 4. As to warding off distraction: he must ward off [temptation] to drop the meditation subject and to let his mind get distracted among the variety of external objects. For if not, just as when a man has entered on a one-foot-wide cliff path, if he looks about here and there without watching his step, he may miss his footing and fall down the cliff, which is perhaps as high as a hundred men, so too, when there is outward distraction, the meditation subject gets neglected and deteriorates. So he should give his attention to it warding off distraction.

66. 5. As to surmounting the concept: this [name-] concept beginning with “head hairs, body hairs” must be surmounted and consciousness established on [the aspect] “repulsive.” For just as when men find a water hole in a forest in a time of drought, they hang up some kind of signal there such as a palm leaf, and people come to bathe and drink guided by the signal, [245] but when the way has become plain with their continual traffic, there is no further need of the signal and they go to bathe and drink there whenever they want, so too, when repulsiveness becomes evident to him as he is giving his attention to the meditation subject through the means of the [name-] concept “head hairs, body hairs,” he must surmount the concept “head hairs, body hairs” and establish consciousness on only the actual repulsiveness.

67. 6. As to successive leaving: in giving his attention he should eventually leave out any [parts] that do not appear to him. For when a beginner gives his attention to head hairs, his attention then carries on till it arrives at the last part, that is, urine and stops there; and when he gives his attention to urine, his attention then carries on till it arrives back at the first part, that is, head hairs, and stops there. As he persists in giving his attention thus, some parts appear to him and others do not. Then he should work on those that have appeared till one out of any two appears the clearer. He should arouse absorption by again and again giving attention to the one that has appeared thus.

68. Here is a simile. Suppose a hunter wanted to catch a monkey that lived in a grove of thirty-two palms, and he shot an arrow through a leaf of the palm that stood at the beginning and gave a shout; then the monkey went leaping successively from palm to palm till it reached the last palm; and when the hunter went there too and did as before, it came back in like manner to the first palm; and being followed thus again and again, after leaping from each place where a shout was given, it eventually jumped on to one palm, and firmly seizing the palm shoot’s leaf spike in the middle, would not leap any more even when shot—so it is with this.

69. The application of the simile is this. The thirty-two parts of the body are like the thirty-two palms in the grove. The monkey is like the mind. The meditator is like the hunter. The range of the meditator’s mind in the body with its thirty-two parts as object is like the monkey’s inhabiting the palm grove of thirty-two palms. The settling down of the meditator’s mind in the last part after going successively [from part to part] when he began by giving his attention to head hairs is like the monkey’s leaping from palm to palm and going to the last palm, [246] when the hunter shot an arrow through the leaf of the palm where it was and gave a shout. Likewise in the return to the beginning. His doing the preliminary work on those parts that have appeared, leaving behind those that did not appear while, as he gave his attention to them again and again, some appeared to him and some did not, is like the monkey’s being followed and leaping up from each place where a shout is given. The meditator’s repeated attention given to the part that in the end appears the more clearly of any two that have appeared to him and his finally reaching absorption, is like the monkey’s eventually stopping in one palm, firmly seizing the palm shoot’s leaf spike in the middle and not leaping up even when shot.

70. There is another simile too. Suppose an alms-food-eater bhikkhu went to live near a village of thirty-two families, and when he got two lots of alms at the first house he left out one [house] beyond it, and next day, when he got three lots of [alms at the first house] he left out two [houses] beyond it, and on the third day he got his bowl full at the first [house], and went to the sitting hall and ate—so it is with this.

71. The thirty-two aspects are like the village with the thirty-two families. The meditator is like the alms-food eater. The meditator’s preliminary work is like the alms-food eater’s going to live near the village. The meditator’s continuing to give attention after leaving out those parts that do not appear and doing his preliminary work on the pair of parts that do appear is like the alms-food eater’s getting two lots of alms at the first house and leaving out one [house] beyond it, and like his next day getting three [lots of alms at the first house] and leaving out two [houses] beyond it. The arousing of absorption by giving attention again and again to that which has appeared the more clearly of two is like the alms-food eater’s getting his bowl full at the first [house] on the third day and then going to the sitting hall and eating.

72. 7. As to absorption: as to absorption part by part. The intention here is this: it should be understood that absorption is brought about in each one of the parts.

73. 8–10. As to the three suttantas: the intention here is this: it should be understood that the three suttantas, namely, those on higher consciousness,[5] on coolness, and on skill in the enlightenment factors, have as their purpose the linking of energy with concentration.

74. 8. Herein, this sutta should be understood to deal with higher consciousness: “Bhikkhus, there are three signs that should be given attention from time to time by a bhikkhu intent on higher consciousness. The sign of concentration should be given attention from time to time, the sign of exertion should be given attention from time to time, the sign of equanimity should be given attention from time to time. [247] If a bhikkhu intent on higher consciousness gives attention only to the sign of concentration, then his consciousness may conduce to idleness. If a bhikkhu intent on higher consciousness gives attention only to the sign of exertion, then his consciousness may conduce to agitation. If a bhikkhu intent on higher consciousness gives attention only to the sign of equanimity, then his consciousness may not become rightly concentrated for the destruction of cankers. But, bhikkhus, when a bhikkhu intent on higher consciousness gives attention from time to time to the sign of concentration … to the sign of exertion … to the sign of equanimity, then his consciousness becomes malleable, wieldy and bright, it is not brittle and becomes rightly concentrated for the destruction of cankers.

75. “Bhikkhus, just as a skilled goldsmith or goldsmith’s apprentice prepares his furnace and heats it up and puts crude gold into it with tongs; and he blows on it from time to time, sprinkles water on it from time to time, and looks on at it from time to time; and if the goldsmith or goldsmith’s apprentice only blew on the crude gold, it would burn and if he only sprinkled water on it, it would cool down, and if he only looked on at it, it would not get rightly refined; but, when the goldsmith or goldsmith’s apprentice blows on the crude gold from time to time, sprinkles water on it from time to time, and looks on at it from time to time, then it becomes malleable, wieldy and bright, it is not brittle, and it submits rightly to being wrought; whatever kind of ornament he wants to work it into, whether a chain or a ring or a necklace or a gold fillet, it serves his purpose.

76. “So too, bhikkhus, there are three signs that should be given attention from time to time by a bhikkhu intent on higher consciousness … becomes rightly concentrated for the destruction of cankers. [248] He attains the ability to be a witness, through realization by direct-knowledge, of any state realizable by direct-knowledge to which he inclines his mind, whenever there is occasion” (A I 256–58).[6]

77. 9. This sutta deals with coolness: “Bhikkhus, when a bhikkhu possesses six things, he is able to realize the supreme coolness. What six? Here, bhikkhus, when consciousness should be restrained, he restrains it; when consciousness should be exerted, he exerts it; when consciousness should be encouraged, he encourages it; when consciousness should be looked on at with equanimity, he looks on at it with equanimity. He is resolute on the superior [state to be attained], he delights in Nibbāna. Possessing these six things a bhikkhu is able to realize the supreme coolness” (A III 435).

78. 10. Skill in the enlightenment factors has already been dealt with in the explanation of skill in absorption (IV.51, 57) in the passage beginning, “Bhikkhus, when the mind is slack, that is not the time for developing the tranquillity enlightenment factor …” (S V 113).

79. So the meditator should make sure that he has apprehended this sevenfold skill in learning well and has properly defined this tenfold skill in giving attention, thus learning the meditation subject properly with both kinds of skill.

[Starting the Practice]

80. If it is convenient for him to live in the same monastery as the teacher, then he need not get it explained in detail thus [to begin with], but as he applies himself to the meditation subject after he has made quite sure about it he can have each successive stage explained as he reaches each distinction.

One who wants to live elsewhere, however, must get it explained to him in detail in the way already given, and he must turn it over and over, getting all the difficulties solved. He should leave an abode of an unsuitable kind as described in the Description of the Earth Kasiṇa, and go to live in a suitable one. Then he should sever the minor impediments (IV.20) and set about the preliminary work for giving attention to repulsiveness.

[The Thirty-two Aspects in Detail]

81. When he sets about it, he should first apprehend the [learning] sign in head hairs. How? The colour should be defined first by plucking out one or two head hairs and placing them on the palm of the hand. [249] He can also look at them in the hair-cutting place, or in a bowl of water or rice gruel. If the ones he sees are black when he sees them, they should be brought to mind as “black;” if white, as “white;” if mixed, they should be brought to mind in accordance with those most prevalent. And as in the case of head hairs, so too the sign should be apprehended visually with the whole of the “skin pentad.”

82. Having apprehended the sign thus and (a) defined all the other parts of the body by colour, shape, direction, location, and delimitation (§58), he should then (b) define repulsiveness in five ways, that is, by colour, shape, odour, habitat, and location.

83. Here is the explanation of all the parts given in successive order.

[Head Hairs]

(a) Firstly head hairs are black in their normal colour, the colour of fresh ariṭṭhaka seeds.[7] As to shape, they are the shape of long round measuring rods.[8] As to direction, they lie in the upper direction. As to location, their location is the wet inner skin that envelops the skull; it is bounded on both sides by the roots of the ears, in front by the forehead, and behind by the nape of the neck.[9] As to delimitation, they are bounded below by the surface of their own roots, which are fixed by entering to the amount of the tip of a rice grain into the inner skin that envelops the head. They are bounded above by space, and all round by each other. There are no two hairs together. This is their delimitation by the similar. Head hairs are not body hairs, and body hairs are not head hairs; being likewise not intermixed with the remaining thirty-one parts, the head hairs are a separate part. This is their delimitation by the dissimilar. Such is the definition of head hairs as to colour and so on.

84. (b) Their definition as to repulsiveness in the five ways, that is, by colour, etc., is as follows. Head hairs are repulsive in colour as well as in shape, odour, habitat, and location.

85. For on seeing the colour of a head hair in a bowl of inviting rice gruel or cooked rice, people are disgusted and say, “This has got hairs in it. Take it away.” So they are repulsive in colour. Also when people are eating at night, they are likewise disgusted by the mere sensation of a hair-shaped akka-bark or makacibark fibre. So they are repulsive in shape.

86. And the odour of head hairs, unless dressed with a smearing of oil, scented with flowers, etc., is most offensive. And it is still worse when they are put in the fire. [250] Even if head hairs are not directly repulsive in colour and shape, still their odour is directly repulsive. Just as a baby’s excrement, as to its colour, is the colour of turmeric and, as to its shape, is the shape of a piece of turmeric root, and just as the bloated carcass of a black dog thrown on a rubbish heap, as to its colour, is the colour of a ripe palmyra fruit and, as to its shape, is the shape of a [mandolin-shaped] drum left face down, and its fangs are like jasmine buds, and so even if both these are not directly repulsive in colour and shape, still their odour is directly repulsive, so too, even if head hairs are not directly repulsive in colour and shape, still their odour is directly repulsive.

87. But just as pot herbs that grow on village sewage in a filthy place are disgusting to civilized people and unusable, so also head hairs are disgusting since they grow on the sewage of pus, blood, urine, dung, bile, phlegm, and the like. This is the repulsive aspect of the habitat.

88. And these head hairs grow on the heap of the [other] thirty-one parts as fungi do on a dung-hill. And owing to the filthy place they grow in they are quite as unappetizing as vegetables growing on a charnel-ground, on a midden, etc., as lotuses or water lilies growing in drains, and so on. This is the repulsive aspect of their location.

89. And as in the case of head hairs, so also the repulsiveness of all the parts should be defined (b) in the same five ways by colour, shape, odour, habitat, and location. All, however, must be defined individually (a) by colour, shape, direction, location, and delimitation, as follows.

[Body Hairs]

90. Herein, firstly, as to natural colour, body, hairs are not pure black like head hairs but blackish brown. As to shape, they are the shape of palm roots with the tips bent down. As to direction, they lie in the two directions. As to location, except for the locations where the head hairs are established, and for the palms of the hands and soles of the feet, they grow in most of the rest of the inner skin that envelops the body. As to delimitation, they are bounded below by the surface of their own roots, which are fixed by entering to the extent of a likhā[10] into the inner skin that envelops the body, above by space, and all round by each other. There are no two body hairs together. This is the delimitation by the similar. But their delimitation by the dissimilar is like that for the head hairs. [Note: These two last sentences are repeated verbatim at the end of the description of each part. They are not translated in the remaining thirty parts].

[Nails]

91. “Nails” is the name for the twenty nail plates. They are all white as to colour. As to shape, they are the shape of fish scales. As to direction: the toenails are in the lower direction; the fingernails are in the upper direction. [251] So they grow in the two directions. As to location, they are fixed on the tips of the backs of the fingers and toes. As to delimitation, they are bounded in the two directions by the flesh of the ends of the fingers and toes, and inside by the flesh of the backs of the fingers and toes, and externally and at the end by space, and all round by each other. There are no two nails together …

[Teeth]

92. There are thirty-two tooth bones in one whose teeth are complete. They are white in colour. As to shape, they are of various shapes; for firstly in the lower row, the four middle teeth are the shape of pumpkin seeds set in a row in a lump of clay; that on each side of them has one root and one point and is the shape of a jasmine bud; each one after that has two roots and two points and is the shape of a wagon prop; then two each side with three roots and three points, then two each side four-rooted and four-pointed. Likewise in the upper row. As to direction, they lie in the upper direction. As to location, they are fixed in the jawbones. As to delimitation, they are bounded by the surface of their own roots which are fixed in the jawbones; they are bounded above by space, and all round by each other. There are no two teeth together …

[Skin (Taca)]

93. The inner skin envelops the whole body. Outside it is what is called the outer cuticle, which is black, brown or yellow in colour, and when that from the whole of the body is compressed together, it amounts to only as much as a jujube-fruit kernel. But as to colour, the skin itself is white; and its whiteness becomes evident when the outer cuticle is destroyed by contact with the flame of a fire or the impact of a blow and so on.

94. As to shape, it is the shape of the body in brief. But in detail, the skin of the toes is the shape of silkworms’ cocoons; the skin of the back of the foot is the shape of shoes with uppers; the skin of the calf is the shape of a palm leaf wrapping cooked rice; the skin of the thighs is the shape of a long sack full of paddy; the skin of the buttocks is the shape of a cloth strainer full of water; the skin of the back is the shape of hide streched over a plank;the skin of the belly is the shape of the hide stretched over the body of a lute; the skin of the chest is more or less square; the skin of both arms is the shape of the hide stretched over a quiver; the skin of the backs of the hands is the shape of a razor box, or the shape of a comb case; the skin of the fingers is the shape of a key box; the skin of the neck is the shape of a collar for the throat; the skin of the face [252] is the shape of an insects’ nest full of holes; the skin of the head is the shape of a bowl bag.

95. The meditator who is discerning the skin should first define the inner skin that covers the face, working his knowledge over the face beginning with the upper lip. Next, the inner skin of the frontal bone. Next, he should define the inner skin of the head, separating, as it were, the inner skin’s connection with the bone by inserting his knowledge in between the cranium bone and the inner skin of the head, as he might his hand in between the bag and the bowl put in the bag. Next, the inner skin of the shoulders. Next, the inner skin of the right arm forwards and backwards; and then in the same way the inner skin of the left arm. Next, after defining the inner skin of the back, he should define the inner skin of the right leg forwards and backwards; then the inner skin of the left leg in the same way. Next, the inner skin of the groin, the paunch, the bosom and the neck should be successively defined. Then, after defining the inner skin of the lower jaw next after that of the neck, he should finish on arriving at the lower lip. When he discerns it in the gross in this way, it becomes evident to him more subtly too.

96. As to direction, it lies in both directions. As to location, it covers the whole body. As to delimitation, it is bounded below by its fixed surface, and above by space …

[Flesh]

97. There are nine hundred pieces of flesh. As to colour, it is all red, like kiṃsuka flowers. As to shape, the flesh of the calves is the shape of cooked rice in a palmleaf bag. The flesh of the thighs is the shape of a rolling pin.[11] The flesh of the buttocks is the shape of the end of an oven. The flesh of the back is the shape of a slab of palm sugar. The flesh between each two ribs is the shape of clay mortar squeezed thin in a flattened opening. The flesh of the breast is the shape of a lump of clay made into a ball and flung down. The flesh of the two upper arms is the shape of a large skinned rat and twice the size. When he discerns it grossly in this way, it becomes evident to him subtly too.

98. As to direction, it lies in both directions. As to location, it is plastered over the three hundred and odd bones. [253] As to delimitation, it is bounded below by its surface, which is fixed on to the collection of bones, and above by the skin, and all round each by each other piece …

[Sinews]

99. There are nine hundred sinews. As to colour, all the sinews are white. As to shape, they have various shapes. For five of great sinews that bind the body together start out from the upper part of the neck and descend by the front, and five more by the back, and then five by the right and five by the left. And of those that bind the right hand, five descend by the front of the hand and five by the back; likewise those that bind the left hand. And of those that bind the right foot, five descend by the front and five by the back; likewise those that bind the left foot. So there are sixty great sinews called “body supporters” which descend [from the neck] and bind the body together; and they are also called “tendons.” They are all the shape of yam shoots. But there are others scattered over various parts of the body, which are finer than the last-named. They are the shape of strings and cords. There are others still finer, the shape of creepers. Others still finer are the shape of large lute strings. Yet others are the shape of coarse thread. The sinews in the backs of the hands and feet are the shape of a bird’s claw. The sinews in the head are the shape of children’s head nets. The sinews in the back are the shape of a wet net spread out in the sun. The rest of the sinews, following the various limbs, are the shape of a net jacket fitted to the body.

100. As to direction, they lie in the two directions. As to location, they are to be found binding the bones of the whole body together. As to delimitation, they are bounded below by their surface, which is fixed on to the three hundred bones, and above by the portions that are in contact with the flesh and the inner skin, and all round by each other …

[Bones]

101. Excepting the thirty-two teeth bones, these consist of the remaining sixtyfour hand bones, sixty-four foot bones, sixty-four soft bones dependent on the flesh, two heel bones; then in each leg two ankle bones, two shin bones, one knee bone and one thigh bone; then two hip bones, eighteen spine bones, [254] twentyfour rib bones, fourteen breast bones, one heart bone (sternum), two collar bones, two shoulder blade bones,[12] two upper-arm bones, two pairs of forearm bones, two neck bones, two jaw bones, one nose bone, two eye bones, two ear bones, one frontal bone, one occipital bone, nine sincipital bones. So there are exactly three hundred bones. As to colour, they are all white. As to shape, they are of various shapes.

102. Herein, the end bones of the toes are the shape of kataka seeds. Those next to them in the middle sections are the shape of jackfruit seeds. The bones of the base sections are the shape of small drums. The bones of the back of the foot are the shape of a bunch of bruised yarns. The heel bone is the shape of the seed of a single-stone palmyra fruit.

103. The ankle bones are the shape of [two] play balls bound together. The shin bones, in the place where they rest on the ankle bones, are the shape of a sindi shoot without the skin removed. The small shin bone is the shape of a[toy] bow stick. The large one is the shape of a shrivelled snake’s back. The knee bone is the shape of a lump of froth melted on one side. Herein, the place where the shin bone rests on it is the shape of a blunt cow’s horn. The thigh bone is the shape of a badly-pared[13] handle for an axe or hatchet. The place where it fits into the hip bone is the shape of a play ball. The place in the hip bone where it is set is the shape of a big punnāga fruit with the end cut off.

104. The two hip bones, when fastened together, are the shape of the ringfastening of a smith’s hammer. The buttock bone on the end [of them] is the shape of an inverted snake’s hood. It is perforated in seven or eight places. The spine bones are internally the shape of lead-sheet pipes put one on top of the other;externally they are the shape of a string of beads. They have two or three rows of projections next to each other like the teeth of a saw.

105. Of the twenty-four rib bones, the incomplete ones are the shape of incomplete sabres, [255] and the complete ones are the shape of complete sabres; all together they are like the outspread wings of a white cock. The fourteen breast bones are the shape of an old chariot frame.[14] The heart bone (sternum) is the shape of the bowl of a spoon. The collar bones are the shape of small metal knife handles. The shoulderblade bones are the shape of a Sinhalese hoe worn down on one side.

106. The upper-arm bones are the shape of looking glass handles. The forearm bones are the shape of a twin palm’s trunks. The wrist bones are the shape of lead-sheet pipes stuck together. The bones of the back of the hand are the shape of a bundle of bruised yams. As to the fingers, the bones of the base sections are the shape of small drums; those of the middle sections are the shape of immature jackfruit seeds; those of the end sections are the shape of kataka seeds.

107. The seven neck bones are the shape of rings of bamboo stem threaded one after the other on a stick. The lower jawbone is the shape of a smith’s iron hammer ring-fastening. The upper one is the shape of a knife for scraping [the rind off sugarcanes]. The bones of the eye sockets and nostril sockets are the shape of young palmyra seeds with the kernels removed. The frontal bone is the shape of an inverted bowl made of a shell. The bones of the ear-holes are the shape of barbers’ razor boxes. The bone in the place where a cloth is tied [round the head] above the frontal bone and the ear holes is the shape of a piece of curled-up toffee flake.[15] The occipital bone is the shape of a lopsided coconut with a hole cut in the end. The sincipital bones are the shape of a dish made of an old gourd held together with stitches.

108. As to direction, they lie in both directions. As to location, they are to be found indiscriminately throughout the whole body. But in particular here, the head bones rest on the neck bones, the neck bones on the spine bones, the spine bones on the hip bones, the hip bones on the thigh bones, the thigh bones on the knee bones, the knee bones on the shin bones, the shin bones on the ankle bones, the ankle bones on the bones of the back of the foot. As to delimitation, they are bounded inside by the bone marrow, above by the flesh, at the ends and at the roots by each other …

[Bone Marrow]

109. This is the marrow inside the various bones. As to colour, it is white. As to shape, [256] that inside each large bone is the shape of a large cane shoot moistened and inserted into a bamboo tube. That inside each small bone is the shape of a slender cane shoot moistened and inserted in a section of bamboo twig. As to direction, it lies in both directions. As to location, it is set inside the bones. As to delimitation, it is delimited by the inner surface of the bones …

[Kidney]

110. This is two pieces of flesh with a single ligature. As to colour, it is dull red, the colour of pālibhaddaka (coral tree) seeds. As to shape, it is the shape of a pair of child’s play balls; or it is the shape of a pair of mango fruits attached to a single stalk. As to direction, it lies in the upper direction. As to location, it is to be found on either side of the heart flesh, being fastened by a stout sinew that starts out with one root from the base of the neck and divides into two after going a short way. As to delimitation, the kidney is bounded by what appertains to kidney …

[Heart]

111. This is the heart flesh. As to colour, it is the colour of the back of a red-lotus petal. As to shape, it is the shape of a lotus bud with the outer petals removed and turned upside down; it is smooth outside, and inside it is like the interior of a kosātakī (loofah gourd). In those who possess understanding it is a little expanded; in those without understanding it is still only a bud. Inside it there is a hollow the size of a punnāga seed’s bed where half a pasata measure of blood is kept, with which as their support the mind element and mind-consciousness element occur.

112. That in one of greedy temperament is red; that in one of hating temperament is black;that in one of deluded temperament is like water that meat has been washed in;that in one of speculative temperament is like lentil soup in colour; that in one of faithful temperament is the colour of [yellow] kanikāra flowers;that in one of understanding temperament is limpid, clear, unturbid, bright, pure, like a washed gem of pure water, and it seems to shine.

113. As to direction, it lies in the upper direction. As to location, it is to be found in the middle between the two breasts, inside the body. As to delimitation, it is bounded by what appertains to heart … [257]

[Liver]

114. This is a twin slab of flesh. As to colour, it is a brownish shade of red, the colour of the not-too-red backs of white water-lily petals. As to shape, with its single root and twin ends, it is the shape of a koviḷāra leaf. In sluggish people it is single and large; in those possessed of understanding there are two or three small ones. As to direction, it lies in the upper direction. As to location, it is to be found on the right side, inside from the two breasts. As to delimitation, it is bounded by what appertains to liver …

[Midriff]

115. This is the covering of the flesh, which is of two kinds, namely, the concealed and the unconcealed. As to colour, both kinds are white, the colour of dukūla (muslin) rags. As to shape, it is the shape of its location. As to direction, the concealed midriff lies in the upper direction, the other in both directions. As to location, the concealed midriff is to be found concealing the heart and kidney; the unconcealed is to be found covering the flesh under the inner skin throughout the whole body. As to delimitation, it is bounded below by the flesh, above by the inner skin, and all round by what appertains to midriff …

[Spleen]

116. This is the flesh of the belly’s “tongue.” As to colour, it is blue, the colour of nigguṇḍi flowers. As to shape, it is seven fingers in size, without attachments, and the shape of a black calf’s tongue. As to direction, it lies in the upper direction. As to location, it is to be found near the upper side of the belly to the left of the heart. When it comes out through a wound a being’s life is terminated. As to delimitation, it is bounded by what appertains to spleen …

[Lungs]

117. The flesh of the lungs is divided up into two or three pieces of flesh. As to colour, it is red, the colour of not very ripe udumbara fig fruits. As to shape, it is the shape of an unevenly cut thick slice of cake. Inside, it is insipid and lacks nutritive essence, like a lump of chewed straw, because it is affected by the heat of the kamma-born fire [element] that springs up when there is need of something to eat and drink. As to direction, it lies in the upper direction. As to location, it is to be found inside the body between the two breasts, hanging above the heart [258] and liver and concealing them. As to delimitation, it is bounded by what appertains to lungs …

[Bowel]

118. This is the bowel tube; it is looped[17] in twenty-one places, and in a man it is thirty-two hands long, and in a woman, twenty-eight hands. As to colour, it is white, the colour of lime [mixed] with sand. As to shape, it is the shape of a beheaded snake coiled up and put in a trough of blood. As to direction, it lies in the two directions. As to location, it is fastened above at the gullet and below to the excrement passage (rectum), so it is to be found inside the body between the limits of the gullet and the excrement passage. As to delimitation, it is bounded by what pertains to bowel …

[Entrails (Mesentery)]

119. This is the fastening in the places where the bowel is coiled. As to colour, it is white, the colour of dakasītalika[18] (white edible water lily) roots. As to shape, it is the shape of those roots too. As to direction, it lies in the two directions. As to location, it is to be found inside the twenty-one coils of the bowel, like the strings to be found inside rope-rings for wiping the feet on, sewing them together, and it fastens the bowel’s coils together so that they do not slip down in those working with hoes, axes, etc., as the marionette-strings do the marionette’s wooden [limbs] at the time of the marionette’s being pulled along. As to delimitation, it is bounded by what appertains to entrails …

[Gorge]

120. This is what has been eaten, drunk, chewed and tasted, and is present in the stomach. As to colour, it is the colour of swallowed food. As to shape, it is the shape of rice loosely tied in a cloth strainer. As to direction, it is in the upper direction. As to location, it is in the stomach.

121. What is called the “stomach” is [a part of] the bowel-membrane, which is like the swelling [of air] produced in the middle of a length of wet cloth when it is being [twisted and] wrung out from the two ends. It is smooth outside. Inside, it is like a balloon of cloth[19] soiled by wrapping up meat refuse; or it can be said to be like the inside of the skin of a rotten jack fruit. It is the place where worms dwell seething in tangles: the thirty-two families of worms, such as round worms, boil-producing worms, “palm-splinter” worms, needle-mouthed worms, tapeworms, thread worms, and the rest.[20] When there is no food and drink, [259] etc., present, they leap up shrieking and pounce upon the heart’s flesh; and when food and drink, etc., are swallowed, they wait with uplifted mouths and scramble to snatch the first two or three lumps swallowed. It is these worms’ maternity home, privy, hospital and charnel ground. Just as when it has rained heavily in a time of drought and what has been carried by the water into the cesspit at the gate of an outcaste village—the various kinds of ordure[21] such as urine, excrement, bits of hide and bones and sinews, as well as spittle, snot, blood, etc.—gets mixed up with the mud and water already collected there; and after two or three days the families of worms appear, and it ferments, warmed by the energy of the sun’s heat, frothing and bubbling on the top, quite black in colour, and so utterly stinking and loathsome that one can scarcely go near it or look at it, much less smell or taste it, so too, [the stomach is where] the assortment of food, drink, etc., falls after being pounded up by the tongue and stuck together with spittle and saliva, losing at that moment its virtues of colour, smell, taste, etc., and taking on the appearance of weavers’ paste and dogs’ vomit, then to get soused in the bile and phlegm and wind that have collected there, where it ferments with the energy of the stomach-fire’s heat, seethes with the families of worms, frothing and bubbling on the top, till it turns into utterly stinking nauseating muck, even to hear about which takes away any appetite for food, drink, etc., let alone to see it with the eye of understanding. And when the food, drink, etc., fall into it, they get divided into five parts: the worms eat one part, the stomach-fire bums up another part, another part becomes urine, another part becomes excrement, and one part is turned into nourishment and sustains the blood, flesh and so on.

122. As to delimitation, it is bounded by the stomach lining and by what appertains to gorge …

[Dung]

123. This is excrement. As to colour, it is mostly the colour of eaten food. As to shape, it is the shape of its location. As to direction, it is in the lower direction. As to location, it is to be found in the receptacle for digested food (rectum).

124. The receptacle for digested food is the lowest part at the end of the bowel, between the navel and the root of the spine. [260] It measures eight fingerbreadths in height and resembles a bamboo tube. Just as when rain water falls on a higher level it runs down to fill a lower level and stays there, so too, the receptacle for digested food is where any food, drink, etc., that have fallen into the receptacle for undigested food, have been continuously cooked and simmered by the stomach-fire, and have got as soft as though ground up on a stone, run down to through the cavities of the bowels, and it is pressed down there till it becomes impacted like brown clay pushed into a bamboo joint, and there it stays.

125. As to delimitation, it is bounded by the receptacle for digested food and by what appertains to dung …

[Brain]

126. This is the lumps of marrow to be found inside the skull. As to colour, it is white, the colour of the flesh of a toadstool; it can also be said that it is the colour of turned milk that has not yet become curd. As to shape, it is the shape of its location. As to direction, it belongs to the upper direction. As to location, it is to be found inside the skull, like four lumps of dough put together to correspond with the [skull’s] four sutured sections. As to delimitation, it is bounded by the skull’s inner surface and by what appertains to brain …

[Bile]

127. There are two kinds of bile: local bile and free bile. Herein as to colour, the local bile is the colour of thick madhuka oil; the free bile is the colour of faded ākulī flowers. As to shape, both are the shape of their location. As to direction, the local bile belongs to the upper direction; the other belongs to both directions. As to location, the free bile spreads, like a drop of oil on water, all over the body except for the fleshless parts of the head hairs, body hairs, teeth, nails, and the hard dry skin. When it is disturbed, the eyes become yellow and twitch, and there is shivering and itching[22] of the body. The local bile is situated near the flesh of the liver between the heart and the lungs. It is to be found in the bile container (gall bladder), which is like a large kosātakī (loofah) gourd pip. When it is disturbed, beings go crazy and become demented, they throw off conscience and shame and do the undoable, speak the unspeakable, and think the unthinkable. As to delimitation, it is bounded by what appertains to bile … [261]

[Phlegm]

128. The phlegm is inside the body and it measures a bowlful. As to colour, it is white, the colour of the juice of nāgabalā leaves. As to shape, it is the shape of its location. As to direction, it belongs to the upper direction. As to location, it is to be found on the stomach’s surface. Just as duckweed and green scum on the surface of water divide when a stick or a potsherd is dropped into the water and then spread together again, so too, at the time of eating and drinking, etc., when the food, drink, etc., fall into the stomach, the phlegm divides and then spreads together again. And if it gets weak the stomach becomes utterly disgusting with a smell of ordure, like a ripe boil or a rotten hen’s egg, and then the belchings and the mouth reek with a stench like rotting ordure rising from the stomach, so that the man has to be told, “Go away, your breath smells.” But when it grows plentiful it holds the stench of ordure beneath the surface of the stomach, acting like the wooden lid of a privy. As to delimitation, it is bounded by what appertains to phlegm …

[Pus]

129. Pus is produced by decaying blood. As to colour, it is the colour of bleached leaves; but in a dead body it is the colour of stale thickened gruel. As to shape, it is the shape of its location. As to direction, it belongs to both directions. As to location, however, there is no fixed location for pus where it could be found stored up. Wherever blood stagnates and goes bad in some part of the body damaged by wounds with stumps and thorns, by burns with fire, etc., or where boils, carbuncles, etc., appear, it can be found there. As to delimitation, it is bounded by what appertains to pus …

[Blood]

130. There are two kinds of blood: stored blood and mobile blood. Herein, as to colour, stored blood is the colour of cooked and thickened lac solution; mobile blood is the colour of clear lac solution. As to shape, both are the shape of their locations. As to direction, the stored blood belongs to the upper direction; the other belongs to both directions. As to location, except for the fleshless parts of the head hairs, body hairs, teeth, nails, and the hard dry skin, the mobile blood permeates the whole of the clung-to (kammically-acquired)[23] body by following the network of veins. The stored blood fills the lower part of the liver’s site [262] to the extent of a bowlful, and by its splashing little by little over the heart, kidney and lungs, it keeps the kidney, heart, liver and lungs moist. For it is when it fails to moisten the kidney, heart, etc., that beings become thirsty. As to delimitation, it is bounded by what appertains to blood …

[Sweat]

131. This is the water element that trickles from the pores of the body hairs, and so on. As to colour, it is the colour of clear sesame oil. As to shape, it is the shape of its location. As to direction, it belongs to both directions. As to location, there is no fixed location for sweat where it could always be found like blood. But if the body is heated by the heat of a fire, by the sun’s heat, by a change of temperature, etc., then it trickles from all the pore openings of the head hairs and body hairs, as water does from a bunch of unevenly cut lily-bud stems and lotus stalks pulled up from the water. So its shape should also be understood to correspond to the pore-openings of the head hairs and body hairs. And the meditator who discerns sweat should only give his attention to it as it is to be found filling the pore-openings of the head hairs and body hairs. As to delimitation, it is bounded by what appertains to sweat …

[Fat]

132. This is a thick unguent. As to colour, it is the colour of sliced turmeric. As to shape, firstly in the body of a stout man it is the shape of turmeric-coloured dukūla (muslin) rags placed between the inner skin and the flesh. In the body of a lean man it is the shape of turmeric-coloured dukūla (muslin) rags placed in two or three thicknesses on the shank flesh, thigh flesh, back flesh near the spine, and belly-covering flesh. As to direction, it belongs to both directions. As to location, it permeates the whole of a stout man’s body; it is to be found on a lean man’s shank flesh, and so on. And though it was described as “unguent” above, still it is neither used as oil on the head nor as oil for the nose, etc., because of its utter disgustingness. As to delimitation, it is bounded below by the flesh, above by the inner skin, and all round by what appertains to fat …

[Tears]

133. These are the water element that trickles from the eye. As to colour, they are the colour of clear sesame oil. As to shape, they are the shape of their location. [263] As to direction, they belong to the upper direction. As to location, they are to be found in the eye sockets. But they are not stored in the eye sockets all the while as the bile is in the bile container. But when beings feel joy and laugh uproariously, or feel grief and weep and lament, or eat particular kinds of wrong food, or when their eyes are affected by smoke, dust, dirt, etc., then being originated by the joy, grief, wrong food, or temperature, they fill up the eye sockets or trickle out. And the meditator who discerns tears should discern them only as they are to be found filling the eye sockets. As to delimitation, they are bounded by what appertains to tears …

[Grease]

134. This is a melted unguent. As to colour, it is the colour of coconut oil. Also it can be said to be the colour of oil sprinkled on gruel. As to shape, it is a film the shape of a drop of unguent spread out over still water at the time of bathing. As to direction, it belongs to both directions. As to location, it is to be found mostly on the palms of the hands, backs of the hands, soles of the feet, backs of the feet, tip of the nose, forehead, and points of the shoulders. And it is not always to be found in the melted state in these locations, but when these parts get hot with the heat of a fire, the sun’s heat, upset of temperature or upset of elements, then it spreads here and there in those places like the film from the drop of unguent on the still water at the time of bathing. As to delimitation, it is bounded by what appertains to grease …

[Spittle]

135. This is water element mixed with froth inside the mouth. As to colour, it is white, the colour of the froth. As to shape, it is the shape of its location, or it can be called “the shape of froth.” As to direction, it belongs to the upper direction. As to location, it is to be found on the tongue after it has descended from the cheeks on both sides. And it is not always to be found stored there; but when beings see particular kinds of food, or remember them, or put something hot or bitter or sharp or salty or sour into their mouths, or when their hearts are faint, or nausea arises on some account, then spittle appears and runs down from the cheeks on both sides to settle on the tongue. It is thin at the tip of the tongue, and thick at the root of the tongue. It is capable, without getting used up, of wetting unhusked rice or husked rice or anything else chewable that is put into the mouth, like the water in a pit scooped out in a river sand bank. [264] As to delimitation, it is bounded by what appertains to spittle …

[Snot]

136. This is impurity that trickles out from the brain. As to colour, it is the colour of a young palmyra kernel. As to shape, it is the shape of its location. As to direction, it belongs to the upper direction. As to location, it is to be found filling the nostril cavities. And it is not always to be found stored there; but rather, just as though a man tied up curd in a lotus leaf, which he then pricked with a thorn underneath, and whey oozed out and dripped, so too, when beings weep or suffer a disturbance of elements produced by wrong food or temperature, then the brain inside the head turns into stale phlegm, and it oozes out and comes down by an opening in the palate, and it fills the nostrils and stays there or trickles out. And the meditator who discerns snot should discern it only as it is to be found filling the nostril cavities. As to delimitation, it is bounded by what appertains to snot …

[Oil of the Joints]

137. This is the slimy ordure inside the joints in the body. As to colour, it is the colour of kaṇikāra gum. As to shape, it is the shape of its location. As to direction, it belongs to both directions. As to location, it is to be found inside the hundred and eighty joints, serving the function of lubricating the bones’ joints. If it is weak, when a man gets up or sits down, moves forward or backward, bends or stretches, then his bones creak, and he goes about making a noise like the snapping of fingers, and when he has walked only one or two leagues’ distance, his air element gets upset and his limbs pain him. But if a man has plenty of it, his bones do not creak when he gets up, sits down, etc., and even when he has walked a long distance, his air element does not get upset and his limbs do not pain him. As to delimitation, it is bounded by what appertains to oil of the joints …

[Urine]

138. This is the urine solution. As to colour, it is the colour of bean brine. As to shape, it is the shape of water inside a water pot placed upside down. As to direction, it belongs to the lower direction. As to location, it is to be found inside the bladder. For the bladder sack is called the bladder. Just as when a porous pot with no mouth is put into a cesspool, [265] then the solution from the cesspool gets into the porous pot with no mouth even though no way of entry is evident, so too, while the urinary secretion from the body enters the bladder its way of entry is not evident. Its way of exit, however, is evident. And when the bladder is full of urine, beings feel the need to make water. As to delimitation, it is delimited by the inside of the bladder and by what is similar to urine. This is the delimitation by the similar. But its delimitation by the dissimilar is like that for the head hairs (see note at end of §90).

[The Arising of Absorption]

139. When the meditator has defined the parts beginning with the head hairs in this way by colour, shape, direction, location and delimitation (§58), and he gives his attention in the ways beginning with “following the order, not too quickly” (§61) to their repulsiveness in the five aspects of colour, shape, smell, habitat, and location (§84f.), then at last he surmounts the concept (§66). Then just as when a man with good sight is observing a garland of flowers of thirtytwo colours knotted on a single string and all the flowers become evident to him simultaneously, so too, when the meditator observes this body thus, “There are in this body head hairs,” then all these things become evident to him, as it were, simultaneously. Hence it was said above in the explanation of skill in giving attention: “For when a beginner gives his attention to head hairs, his attention carries on till it arrives at the last part, that is, urine, and stops there” (§67).

140. If he applies his attention externally as well when all the parts have become evident in this way, then human beings, animals, etc., as they go about are divested of their aspect of beings and appear as just assemblages of parts. And when drink, food, etc., is being swallowed by them, it appears as though it were being put in among the assemblage of parts.

141. Then, as he gives his attention to them again and again as “Repulsive, repulsive,” employing the process of “successive leaving,” etc. (§67), eventually absorption arises in him. Herein, the appearance of the head hairs, etc., as to colour, shape, direction, location, and delimitation is the learning sign; their appearance as repulsive in all aspects is the counterpart sign.

As he cultivates and develops that counterpart sign, absorption arises in him, but only of the first jhāna, in the same way as described under foulness as a meditation subject (VI.64f.). And it arises singly in one to whom only one part has become evident, or who has reached absorption in one part and makes no further effort about another.

142. But several first jhānas, according to the number of parts, are produced in one to whom several parts have become evident, or who has reached jhāna in one and also makes further effort about another. As in the case of the Elder Mallaka. [266]

The elder, it seems, took the Elder Abhaya, the Dīgha reciter, by the hand,[24] and after saying “Friend Abhaya, first learn this matter,” he went on: “The Elder Mallaka is an obtainer of thirty-two jhānas in the thirty-two parts. If he enters upon one by night and one by day, he goes on entering upon them for over a fortnight; but if he enters upon one each day, he goes on entering upon them for over a month.”

143. And although this meditation is successful in this way with the first jhāna, it is nevertheless called “mindfulness occupied with the body” because it is successful through the influence of the mindfulness of the colour, shape, and so on.

144. And the bhikkhu who is devoted to this mindfulness occupied with the body “is a conqueror of boredom and delight, and boredom does not conquer him; he dwells transcending boredom as it arises. He is a conqueror of fear and dread, and fear and dread do not conquer him; he dwells transcending fear and dread as they arise. He is one who bears cold and heat … who endures … arisen bodily feelings that are … menacing to life” (M III 97); he becomes an obtainer of the four jhānas based on the colour aspect of the head hairs,[25] etc.; and he comes to penetrate the six kinds of direct-knowledge (see MN 6).

So let a man, if he is wise,

Untiringly devote his days

To mindfulness of body which

Rewards him in so many ways.

This is the section dealing with mindfulness occupied with the body in the detailed treatise.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

In the Aṅguttara text the negative and positive clauses are in the opposite order.

[3]:

Hatthasaṅkhalikā—“the fingers of a pair of clasped hands,” “a row of fingers (aṅgulīpanti) (Vism-mhṭ 246).

[4]:

“For the penetration of the characteristic of foulness, for the observation of repulsiveness as the individual essence” (Vism-mhṭ 246).

[5]:

“The higher consciousness” is a term for jhāna.

[6]:

Vism-mhṭ explains “sati sati āyatane” (rendered here by “whenever there is occasion” with “tasmiṃ tasmiṃ pubbahetu-ādi-kāraṇe sati” (“when there is this or that reason consisting in a previous cause, etc.”); M-a IV 146 says: “Sati sati kāraṇe. Kim pan’ ettha kāraṇan’ti. Abhiññā’ va kāraṇaṃ (‘Whenever there is a reason. But what is the reason here? The direct-knowledge itself is the reason’).”

[7]:

Ariṭṭhaka as a plant is not in PED; see CPD—Sinh penela uṭa.

[8]:

There are various readings.

[9]:

“Galavāṭaka,” here rendered by “nape of the neck,” which the context demands. But elsewhere (e.g. IV.47, VIII.110) “base of the neck” seems indicated, that is, where the neck fits on to the body, or “gullet.”

[10]:

A measure of length, as much as a “louse’s head.”

[11]:

Nisadapota—“rolling pin”: (= silā-puttaka—Vism-mhṭ 250) What is meant is probably the stone roller, thicker in the middle than at the ends, with which curry spices, etc., are normally rolled by hand on a small stone slab in Sri Lanka today.

[12]:

Koṭṭhaṭṭhīni—“shoulder-blade bones”: for koṭṭha (= flat) cf. koṭṭhalika §97; the meaning is demanded by the context, otherwise no mention would be made of these two bones, and the description fits. PED under this ref. has “stomach bone” (?). Should one read a-tikhiṇa (blunt) or ati-khiṇa (very sharp)?

[13]:

Duttacchita—“badly pared”: tacchita, pp. of tacchati to pare (e.g. with an adze);not in PED; see M I 31,124; III 166.

[14]:

Pañjara—“frame”: not quite in this sense in PED.

[15]:

Saṅkuṭitaghaṭapuṇṇapaṭalakhaṇḍa—“a piece of curled-up toffee flake.” The Sinhalese translation suggests the following readings and resolution: saṅkuthita (thickened or boiled down (?), rather than saṅkuṭita, curled up); ghata-puṇṇa ([toffee?] “full of ghee”); paṭala (flake or slab); khaṇḍa (piece).

[16]:

Kilomaka—“midriff”: the rendering is obviously quite inadequate for what is described here, but there is no appropriate English word.

[17]:

Obhagga—“looped”: not in this sense in PED; see obhañjati (XI.64 and PED).

[18]:

Dakasītalika: not in PED; rendered in Sinhalese translation by helmaeli (white edible water lily).

[19]:

Maṃsaka-sambupali-veṭhana-kiliṭṭha-pāvāra-pupphaka-sadisa: this is rendered into Sinhalese by kuṇu mas kasaḷa velu porōnā kaḍek pup (“an inflated piece (or bag) of cloth, which has wrapped rotten meat refuse”). In PED pāvāra is given as “cloak, mantle” and (this ref.) as “the mango tree”; but there seems to be no authority for the rendering “mango tree,” which has nothing to do with this context. Pupphaka (balloon) is not in PED (cf. common Burmese spelling of bubbuḷa (bubble) as pupphuḷa).

[20]:

It would be a mistake to take the renderings of these worms’ names too literally. Gaṇḍuppada (boil-producing worm?) appears only as “earth worm” in PED, which will not do here. The more generally accepted reading seems to take paṭatantuka and suttaka (tape-worm and thread-worm) as two kinds rather than paṭatantusuttaka;neither is in PED.

[21]:

Kuṇapa—“ordure”;PED only gives the meaning “corpse,” which does not fit the meaning either here or, e.g., at XI.21, where the sense of a dead body is inappropriate.

[22]:

Kaṇḍūyati—“to itch”: the verb is not in PED; see kaṇḍu.

[23]:

Upādiṇṇa—“clung-to”: see Ch. XIV, note 23.

[24]:

Reference is sometimes made to the “hand-grasping question” (hattha-gahaka pañhā). It may be to this; but there is another mentioned at the end of the commentary to the Dhātu-Vibhaṅga.

[25]:

The allusion seems to be to the bases of mastery (abhibhāyatana—or better, bases for transcendence); see M II l3 and M-a III 257f.; but see §60.