The gods of northern Buddhism

their history, iconography and progressive evolution through the northern Buddhist countries

by Alice Getty | 1914 | 98,662 words

Indispensable reference for art historians, scholars of Eastern philosophy and religion. Wealth of detailed scholarly information on names, attributes, symbolism, pictorial representations of virtually every major and minor divinity in Mahayana pantheon, as worshipped in Nepal, Tibet, China, Korea, Mongolia, and Japan. 185 black-and-white illustrat...

Chapter XIV - Minor Gods

I. Lokapala.

II. The Five Kings.

III. The Ni-o (Ni-wo).

IV. The Citipati.

V. Nagas and Garudas.

(S.) catur maharaja.

(T.) rgyal-c'en-bshi (the four kings).

(M.) maharaja.

(C.) Hu-shih-ehe (![]() ).

).

The Lokapala, or guardians of the Four Cardinal Points, are believed to dwell on Mount Sumeru (Kailasa) at the gates of the paradise of Sakra (Indra), who is looked upon as a protector of Buddhism.

The four Guardian Kings are mentioned in the earliest Buddhist writings as visiting Gautama while he was in the Tushita heaven waiting for the time to come for him to manifest himself on earth as Manushi-Buddha. They are alluded to in the Nidana-Katha as having been present when Maya's couch was carried to the place of incarnation of the Buddha. They assisted at his birth, and received the Buddha 'on the skin of a spotted tiger'. They held up the hoofs of the horse Kanthaka when Gautama secretly left his palace to go into the wilderness. After his fasting and meditation under the Bodhi-tree, they offered the Buddha four bowls of food, which he miraculously merged into one (patra, v. Glossary). In fact, they assisted at every important event in the life of the Buddha, and were present at his parinirvdna.

Images of the Lokapala were placed at the four sides of the Indian topes (stupa) to guard the sacred relics. The earliest known statues are on the Sanchi Tope, which dates from between the second and first centuries b. c. The Buddhist Guardians were generally represented in full armour standing on Naga demons, [1] while the mounts of the Brahman Lokapala were elephants. [2] They became very popular deities in Tibet, China, and Japan, and were also taken up by the Southern Buddhists of the Hinayana school.

The four Indian Lokapala are:

1, North: Kuvera (Vaisravana), King of the Yakshas (supernatural beings that bring disease).

Symbols: dhvaja (banner) in right hand and mongoose in the left.

Colour: yellow.

2, South: Virudhaka, King of the Khumbhanda (giant demons).

Symbol: sword.

Colour: blue or green.

Instead of the usual helmet, he wears the skin of an elephant's head.

3, East: Dhritarashtra, King of the Gandharvas (demons feeding on incense).

Symbol: stringed instrument.

Colour: white.

He wears a high helmet, on the top of which is a plume and from which hang ribbons and bows.

4, West: Virupaksha, King of the Nagas (serpent-gods).

Symbol: chorten (a small shrine), or a jewel and a serpent.

Colour: red.

Of these four guardian kings, Vaisravana is the only god whose worship, singly, became popular. As the Northern regions were believed to produce endless treasures, the guardian of the North was looked upon as god of Wealth.

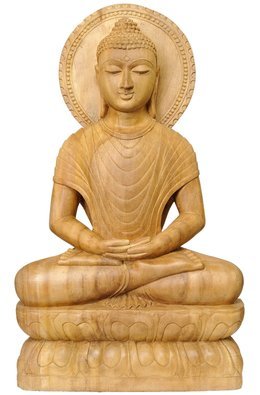

In Japan he is worshipped under the name of Bishamon, and is represented in armour ornamented with the seven precious jewels, and is generally standing on one or two demons. In his left hand he holds either a small shrine or the flaming pearl, while in his right is a jewelled lance (PI. Lin, fig. a).

The mani, or jewel, on the top of his staff, is believed to signify 'completeness of fortune and virtue'. The small caitya, [3] or shrine, represents the Iron Tower in India where Nagarjuna found the Buddhist scriptures. He is represented looking at the shrine, for, as one of the guardians of Buddhism, he must keep watch over its greatest treasures (PI. liv).

A bronze example of Bishamon (Chinese) belonging to Mr. Goloubew is, as far as the author knows, unique. It somewhat resembles the illustration on PI. liv, with the exception that instead of holding the hands in the traditional pose, they are in prayer mudra, and the treasure, balanced on the fore-arms, is not a stupa but an object resembling a temple banner when rolled.

Bishamon is believed to have revealed himself to Shotoku Taishi in battle, and it is said that in the helmet of Shotoku Taishi were four small images of the Lokapala. The Japanese Vaisravana is not, however, god of War, but the god of Good Fortune, and belongs to the group of Seven Gods of Good Fortune (Shi-chi-fu-ku-jin). With the exception of Benten he is the only god of the group worshipped to any extent singly. Amoghavajra introduced the worship of the Celestial Guardians of the Four Quarters of the Heavens into China in the eighth century of our era, and one often sees them at the temple gates.

The Chinese look upon them as symbolizing the four seasons.

1, North: To-wen (![]() ) (Kuvera) or Wei-p'o — yellow (autumn: a black warrior).

) (Kuvera) or Wei-p'o — yellow (autumn: a black warrior).

Symbols: right hand, a banner or lance, left hand, a pearl, or stupa or mongoose, out of the mouth of which pour jewels.

2, South: Tseng-chang (![]() ) — blue (spring: red bird); may stand on a monkey and a demon.

) — blue (spring: red bird); may stand on a monkey and a demon.

Symbol: sword.

3, East: Ch'i-kwo (![]() ) — white (summer: blue dragon).

) — white (summer: blue dragon).

Symbols: stringed instrument.

4, West: Kwang-mu (![]() ) — red (winter: white tiger); may also be green with red beard.

) — red (winter: white tiger); may also be green with red beard.

Symbols: right hand, a caifya, left hand, a serpent.

In Chinese paintings the colours of the Four Guardians often vary and they are sometimes all represented flesh colour. They may also have no symbols, with the exception of To-wen, who always holds the treasure.

The Shi-tenno or Japanese Celestial Guardians of the Four Cardinal Points are:

1, North: Bishamon (Kuvera). [4]

Symbols: caitya (small shrine) and lance or flag.

2, South: Komoku.

3, East: Jikohu.

4, West: Zocho.

They are also represented as warriors, and are generally standing on demons. In the illustrations in the Butzuzo Zui, with the exception of Bishamon, they hold no symbols.

In Chinese Turkestan representations of the Four Guardian Kings were found by Sir Aurel Stein at Tun-huang, on temple banners, and by Herr von Le Coq at Turfan, in frescoes, which are now at the Museum fur Volkerkunde in Berlin. Vaisravana was also represented alone in frescoes at the entrance to the temples opposite Hariti (v. Hariti). According to Waddell she is a form of his consort, Vasudhara (v. Kuvera). In all the representations of the Lokapala found in Chinese Turkestan they are elaborately dressed, usually in armour, holding their respective symbols, and also standing, as a rule, on crouching demons.

The five great Kings

(T.) sku-lnga (or Dam-can) (five persons or bodies), or Na'i-chin chon jon (the guardians of [the oracle] Nauchin).

( M.) tahun qaghan (five emperors),

The Five Great Kings are objects of very active worship in Tibet as they are believed to

'protect man efficaciously against evil spirits and enable him to attain the accomplishment of every wish' (Schlagintweit).

According to Waddell, these king-fiends, or spirits of demonified heroes, are supposed to have been originally five brothers who came from Northern Mongolia.

They are said to have been 'kings';

- of the East, mystically called 'the Body';

- of the West, 'Speech'; of the North, 'Deeds';

- of the South, 'Learning'; and

- of the centre — difficult to determine.

They were necromancers and astrologers, and became oracles of different monasteries.

The oracle of Na-ch'un [5] was brought to Tibet by Padmasambhava, and after being admitted to the Lamaist order was made state-oracle. He is believed to incarnate himself in every successive religious guardian of the monasteries, who is called after him, Choi-chong (C'os-rje).

The names of the Five Great Kings are the following: [6]

- Bi-har, the special protector of monasteries, who rides on a red tiger.

- Choi-chung, incarnate in the state-oracles, who rides on a yellow lion (PL lvi, fig. c).

- Dahla is the tutelary god of warriors, and rides on a yellow horse.

- Luvang, the god of the Nagas, rides on a blue crocodile.

- Tokchoi, rides on a yellow deer.

In this form they accompany the thirty-five Buddhas of Confession. According to Schlagintweit, when one of these gods is represented alone, he is accompanied by:

Damchan dorje legpa, on a camel.

Ts'angs-pa, on a ram.

Chebu damchan, on a goat.

According to Grunwedel, it is Dam-can rdor-legs who is on the goat and not on the camel (PI. LVI, fig. d).

All of the Five Kings wear a broad-brimmed hat and long, flowing garments which, if painted, are red with a green border.

It is claimed that when Padmasambhava wished to build the convent of bSamyas he forced the Five Kings to make a vow to protect it. For that reason they are called Dam-can, or 'he who has made a vow'.

According to certain accounts, the chief of the Kings is Pe-har or Pe-dkar, who is probably the 'Bi-har' quoted above. He has six arms and is white, seated on a white lion. He brandishes a sword, knife, and bow and arrow. The president of the Five Kings is said to be identical with the fourth guardian of the world, Dhritarashtra, and is also claimed by others to be the president of the Four Lokapala.

The second King is blue, on a white elephant. He has two arms, and holds a knife and lasso.

The third King is blue, on a blue lion. He holds a vajra and a khakkhara (alarm staff).

The fourth King is red on a blue mule, and holds an elephant goad and a bludgeon.

The fifth King is green on a black horse, and holds an axe.

In the paintings of the Five Kings, Padmasambhava is usually represented above Pe-har, the chief of the Kings.

NI-O (Ni-wo)

The Japanese god, Ni-o, guardian of the Buddhist scriptures, is believed to reside on the four peaks of Mount Sumeru, the centre of the universe, but will manifest himself whenever enshrined and worshipped with proper ceremonies.

Although his name Ni-o literally means 'two kings', he is, in reality, one deity, but may be represented by any number of gods, even, according to the Suranhgamasamadhi sutra, as many as 'ten times the grains of sand of the river Ganges'. The Shobonenkyo call the deity Misshakukongo.

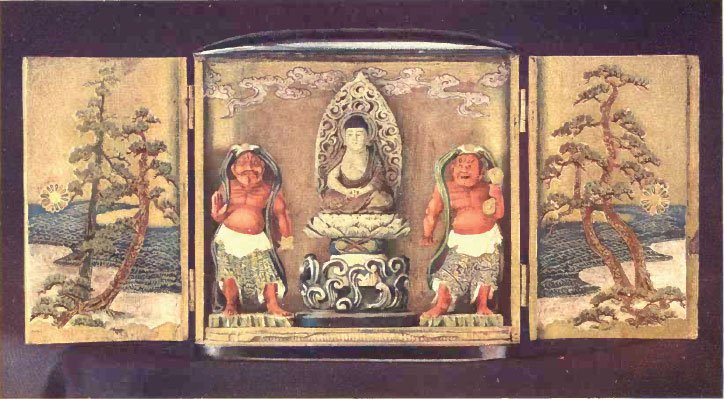

Ni-o, however, is best known in his dual form of Missaku and Kongo, [7] or the two guardians enshrined on either side of the gateway of Buddhist temples (PI. lvii).

These 'two kings' probably find their origin in a Japanese legend, which runs to the effect that there was once a king whose first wife bore him a thousand sons, whom he wished to acquire perfect enlightenment. His second queen bore him two sons, one of whom desired to turn the Wheel of the Law for his thousand brothers, while the other vowed to protect the Law which his brother preached. The former was called Missaku, and the latter Kongo.

The king Kongo is the Japanese Vajrapani. He is represented at the right of the gateway of a Buddhist temple and holds a vajra (thunderbolt). The name 'Kongo' means vajra, or thunderbolt, with which the god is believed to destroy all evil.

The king Missaku is enshrined at the left of the gateway, and is believed to propagate goodness.

The 'two Kings' are sometimes termed the Vldyaraja, and, as such, are called Raga (Aizen) and Acala (Fudo), and are represented by the Mandala of the Two Parts. [8]

Raga belongs to the Garbhadhatu (matrix section), or the material world of the five elements: earth, water, fire, air, and ether. He is represented by the sound 'a' and his statues have the mouth open.

Acala belongs to the Vajradhatu (diamond section), or spiritual world of one element: the mind. He is represented by the sound 'hum', and his statues have the mouth closed.

The deity Ni-o is thus the union of the Spiritual with the Material, or the 'two Kings' in one. In other words, he is the dual form of Vairocana (Dai-nichi Nyorai).

The Citipati

(T.) dur-k'rod bdag-po (the lord or master of the cemetery).

The Citipati are two skeletons, one of a man and the other of a woman, who are represented with arms and legs interlaced, dancing the Tsam dance on two corpses. Each brandishes a sceptre topped by a skull, and one holds a skull-cup and the other a vase, or else they both carry the same symbol (PI. lii, fig. b). They are usually represented in the suite of Yama, but may also accompany the dakim, Naro-mk'haspyod-ma.

In Pander's Pantheon (No. 253) they are represented each on a separate lotusflower and not following the text.

According to a Northern Buddhist legend, the Citipati were, in a former existence, two ascetics who were once lost in such deep meditation that they did not notice that a thief had cut off their heads and thrown them in the dust. Since that time they have been ferocious enemies of the thief and have vowed eternal vengeance. It somewhat resembles the legend of Yama.

Nagas and Garudas

The Nagas, or serpent-gods, are minor deities, but superior to man, and believed to be the protectors of the Law of Buddha. In fact, Buddhist legend claims that the sacred book, the Prajnaparamita, was put under the protection of the Nagas by Gautama Buddha himself until such a time as the human race should have acquired sufficient knowledge to understand it. In the first century of our era, the sage Nagarjuna claimed to have received from the Nagas the Prajndpdramitd, on which he founded the Mahayana School.

The seat of Naga worship was in Kashmir and spread south into India along the Indus. When Hiuen-tsang entered the valley in the beginning of the seventh century A. D. he found, in almost every place he visited, a shrine dedicated to a local Naga. He relates that it was even believed that a member of the Sakya family (that of Gautama Buddha) had married the daughter of a serpent-king, and he also tells of a Buddhist priest who was reborn as a serpent because he 'killed' the Elapatra-tree. [9] In a Tibetan scroll [10] it is related, in regard to the Elapatra Naga, that he assumed the guise of a monarch in order to hear the Blessed One preach.

The All-Knowing Buddha, perceiving him among his hearers, addressed him as follows:

'O King of Snakes, during the ministry of Buddha Kasyapa you violated the rules of moral conduct, for which you were condemned to be born a snake. Have you now come here, assuming a false appearance, like a hypocrite, while I am preaching? Assume your own shape and listen to my sermons, if your nature permits you to do so!'

Next day there appeared in the audience a huge serpent on whose head was grown an Elapatra-tree. His body measured many miles, for while his head came to hear Buddha's sermon in Rajagriha, his tail lay in Taxila.

In Japan there is a legend in regard to a priest who was reborn as a fish, out of whose head grew a huge tree. [11] It is probably a version of the Elapatra Naga legend.

The Nagas play an important rdle in the legend of Gautama Buddha. They assisted at his birth and gave him his first bath (PL vil). They came to hear him preach and became his disciples. It is recounted that once when Buddha remained in a state of samadhi (form of deepest meditation) for seven days, under a tree near a pond, the blind Naga that lay in the pool was restored to vision by the light that shone from the Buddha's body and became his disciple. When Mara, god of Evil, unchained the fury of the elements to disturb Buddha's meditation, Mucalinda, a serpent-king, wound his coils about him and spread his hood over the Tathagati's head to protect him during his samadhi (PI. VI, fig. a).

The serpent, from the annual renewal of its skin, is a symbol of immortality, and when represented with its tail in its mouth forming a circle symbolizes the Yoga principle of Union, or the Circle of Regeneration. The Nagaraja Mucalinda, who wound his coils around the body of the Buddha to protect him from the temptations of the god of Evil, typifies the impenetrable armour which the Tathagata fashions for himself by the observance of the ten Paramitas. The Naga god protecting Sakyamuni may be represented with five, seven, or many heads, the last form being purely Indian (PI. xi, figs, a and b). The nimbus of Amoghasiddha in Nepal is represented surrounded by Nagas, and that of Nagarjuna has seven overhanging serpents.

In Kashmir serpentworship existed as early as the fifth century B. c. In Ceylon the serpentworshippers were converted to Buddhism in the third century B. c, but the worship has now practically disappeared, while in India the Naga god is still reverenced, especially in the South.

The Indian representations of the Naga gods from the third century b. c. to the twelfth a. d. were of human form, with, behind the head, a spread cobra's hood having three, five, or seven heads. After the twelfth century, the Nagas were represented with the body ending in a serpent's tail. When the cobra-hood had only three or five heads, the tail was spotted; if seven or nine heads, the serpent was represented covered with scales. The more modern representations are merely that of a cobra capella with the hood spread.

The Chinese used the snake symbol much less than that of the dragon, although the Naga god was worshipped in China from the earliest times. Fergusson [12] mentions that

'two heaven-sent serpents watched over the first washing of Confucius'.

In Japan the serpent has been worshipped from prehistoric times, and many Naga shrines may still be found throughout Japan. At Kamakura there is a temple dedicated to a local Naga, who is represented coiled in spiral shape with the head of a bearded man [13] (PI. lviii). It is worshipped as the goddess Benten by the common people, but is probably a relic of serpent (or phallic) worship. The goddess Benten (Benzai-ten), one of the seven gods of Good Luck, is usually represented riding on a snake (or a dragon). As she is a very popular divinity, it may be that the serpent has become identified with her as an object of adoration. Her shrines as related above are generally on islands, and always near a river, lake, or the sea. When the snake is white, it is believed to be a special manifestation of the Indian goddess Sarasvati.

On PI. lix, fig. a, there is a small household shrine of a Naga god in bronze with a human head, resembling the example on PI. LVIII, which is in wood, and claimed at the temple to have been carved by Kobo Daishi.

According to Hindu mythology, the Nagas were in constant terror of the Garudas, or fabulous golden-winged birds, and especially of their king. This gigantic bird would fly up into a huge tree called Kutasalmali, which is at the north of the Great Ocean, and flapping his wings to divide the waters, swoop down upon the serpent-gods, pick them up with his beak, and eat them. In their distress the Nagas that had been converted to Buddhism appealed to the Buddha to protect them against their mortal enemies, and he appointed the god Vajrapani [14] their special protector. The Tathagata then gave them his monastic garment, which was divided into infinitesimal pieces and distributed among them. No Naga, with this inviolable talisman, could be harmed by a Garuda. Vajrapani, as related above, in order to combat these formidable birds, assumed the shape of a Garuda.

One of the Garuda's most formidable enemies is Nanda, the Nagaraja, king of the serpents. He is represented in human form as far as the waist, and the rest of the body as a serpent. He may have one head, with a serpent crown, and two hands holding a serpent; or have four heads and six arms, two of the hands of which are drawing a bow (PI. lix, fig. c).

The Nagas were not considered malignant gods, but, on the contrary, were kindly disposed towards mankind. They were believed to control the rain-clouds, and, when properly propitiated, would protect from lightning, bring beneficial showers, or stop too abundant rains.

The king of the Nagas is Virupaksha, one of the four Lokapala, or Celestial Guardians of the Four Cardinal Points. His kingdom is the continent west of Mount Meru, which was supposed to be the centre of the universe; but the chief residence of the Nagas is Bhogavati, 3,000 yoganas under the sea.

| PLATE LIV |

|

| To-wen (Bishamon) |

| PLATE LV |

|

| Dakini |

| PLATE LVI | ||

|

|

|

| a. Varuna | b. Varuna | |

|

|

|

| c. Undetermined | d. Dam-can | |

| PLATE LVII |

|

| Amida with the Ni-o |

| PLATE LVIII |

|

| Naga god. Printed mamori or charm from the Enkakuji temple, Kamakura, Japan |

| PLATE LIX | ||

|

||

| a. Naga | ||

|

|

|

| b. Garuda | c. Najaraja | |

| PLATE LX | ||

|

|

|

| a. Mi-la ras-pa | b. Ts'on-k'a-pa (?) | |

|

|

|

| c. Man-la | d. Undetermined | |

| PLATE LXI |

.jpg) |

|

a. Vasudhana b. Bhirukuti (Two leaves from a Nepalese book) |

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

L. A. Waddell, 'Evolution of the Buddhist cult; its gods, images, and art', The Imperial Asiatic Quarterly Review, January, 1912.

[2]:

In Japan the Lokapala are usually represented treading on demons, but on PL iv, fig. a, they are supported by elephants.

[3]:

v. Glossary.

[4]:

PI. LIII, fig. c. 2

[5]:

Waddell, Lamaism, p. 478.

[6]:

Schlagintweit, Buddhism in Tibet, p. 157.

[7]:

From the Myokyojochinsho.

Name: Misshaku -Kongo

Manifestation: Raga (Aizen) - Acala (Fudo)

Mouth: open - closed

Heaven: Garbha - Vajra

Germ: a - hum

[8]:

v. Vairocana.

[9]:

For legend v. Journal and Text of the Buddhist Text Society of India, vol. ii, Part I, 1894, p. 3.

[10]:

Translated by Satis Chandra Vidyabhusana, Memoirs of the Asiatic Society of Bengal.

[11]:

For legend see the Open Court for June, 1911.

[12]:

Tree and Serpent Worship.

[13]:

On the tip of its tail is balanced a cintamani, in the form of a flaming pearl. In the Nepalese MS. Add. 864, in the University Library, Cambridge, the four-headed Naga, on the coils of which the Buddha is seated, has also the cintamani on the tip of its tail.

[14]:

v. Vajrapani.