The gods of northern Buddhism

their history, iconography and progressive evolution through the northern Buddhist countries

by Alice Getty | 1914 | 98,662 words

Indispensable reference for art historians, scholars of Eastern philosophy and religion. Wealth of detailed scholarly information on names, attributes, symbolism, pictorial representations of virtually every major and minor divinity in Mahayana pantheon, as worshipped in Nepal, Tibet, China, Korea, Mongolia, and Japan. 185 black-and-white illustrat...

Chapter VIII - Forms Of Kwan-non

God of Mercy.

(S.) Avalokitetrara.

(C.) Kwan-yin.

Kwan-non holding a child.

(C.) Sung-tse Kwan yin.

(J.) Koyasu Kwan-non.

Kwan-non, god (or goddess) of Mercy, is the Japanese form of the Chinese divinity Kwan-yin, manifestation of Avalokitesvara. His worship is said to have been introduced into Japan during the reign of the Empress Suiko (593-628), forty years after the introduction of Buddhism, [1] and has lasted up to the present time.

There are three different non-Tantra manifestations of Kwan-non found in the temples and museums of Japan. The first, and probably the most ancient, is modelled after the Indian representation of Avalokitesvara in his non-Tantra form of Padmapani: a slight, youthful figure, with long-lobed ears, dressed like an Indian prince, and with often a moustache slightly outlining the upper lip.

The second form, which was brought into Japan from India and Central Asia via China, is a female figure, seated or standing, with graceful, flowing garments, and a crown or head-drapery.

The third form is Japanese in aspect, but the long-lobed ears are Indian and the folds of the drapery indicate the influence of the Gandhara School. The figure is seated with the head leaning on the right hand.

The evident confusion in art in regard to the sex of Kwan-non has also existed among the worshippers even to the present day. The common people pray to the divinity as 'goddess of Mercy', while the priests and the more educated classes worship the god as a masculine deity, for he is believed to dwell on the right hand of Amitabha in the Western Paradise of Sukhavati, [2] where no woman without attaining masculinity, through merit, can enter. Some of the sects, however, worship Kwannon as sexless, for it is claimed that as objects of worship, all male or female beings should be looked upon as of no fixed sex.

Professor Lloyd says in his Creed of Half Japan that the Bodhisattva might be considered as non-sexual, or bi-sexual, while in his Shinran he writes:

'It is a mistake to speak of Kwan-non as a female deity. Kwan-non is the son of Amitabha, capable of appearing in many forms, male or female, human or animal, according to circumstances. But he is never manifested except as a means of practically demonstrating the divine compassion for a suffering creation.'

It is very difficult to determine when the different forms of Kwan-non appeared in Japan. Chiso, a Chinese priest, is said to have brought Buddhist images into Japan A. D. 564 (or 571). In the Nihongi there is the following reference to a statue of Avalokitesvara:

'In the seventh month, after the Empress Suiko's reign (a. d. 593-628), the king of Shiraki (a portion of the present Korea) sent an ambassador to the Japanese court to make homage to the empress and to present her with a gold-copper statue of Avalokitesvara. Prince Shotoku, who was regent to the empress, accepting it, ordered Hata-no-Ka-wakatsu to put up a sanctuary for the image.'

It is also recorded elsewhere that Shotoku put up statues and shrines to Kwan-non, and that whenever he was troubled by any serious state affairs, he shut himself up in one of the shrines and offered prayers to Avalokita.

At the end of the seventh century, Dosho, a Japanese priest, went to China to study Buddhism with Hiuen-tsang, [3] the famous Buddhist pilgrim and scholar, and brought back with him many Buddhist images. Hiuen-tsang was a fervent admirer of Avalokitesvara, [4] although he was not worshipped by the Hosso sect. It is therefore not improbable that among the images that Dosho brought back, there were representations of Avalokitesvara, possibly in both the masculine and feminine forms.

The foreign gods, however, were not popular until the ninth century, when the Japanese Buddhist priest Kukai (Kobo Daishi) returned from China, where he had been studying the dogmas of the Yogacarya, or Tantra school, under Hiu-kio (Kei-kwa), the celebrated Buddhist scholar.

After founding the Shin-gon [5] sect, he proceeded to popularize the divinities of the Mahayana by the same tactics that his master, Hiu-kio, had employed, with success, in China. Hiu-kio, in his turn, had adopted the method of Asanga in India several centuries before, and the method was a very simple one. It consisted in accepting the gods of a people one intended to convert, at the same time proclaiming that these gods were manifestations of the divinities one was about to impose.

Kukai went to the holy Shinto shrine of lse and prostrated himself before the altar of the god [6] of Abundant Food, Toyuki-Bime no Kami. After days of fasting he succeeded in getting a revelation. The god appeared to him, expressed his belief in the power of the gods of the Mahayana, and informed him that the Shinto gods were avatars and incarnations of the Buddhist divinities. And so, with the approbation of this most popular and powerful deity, he began the work of revealing the names of the Buddhist gods, of which the Shinto divinities were but manifestations, and of popularizing them.

As Kobo Daishi brought the Tantra doctrine into Japan, it is not improbable that he also introduced the Tantra form of Avalokitesvara, the Sen-ju, or thousandarmed Kwan-non, for it is recorded that, like Dosho, he brought back images with him when he returned from China.

There are seven forms of Kwan-non in Japan, which show the influence of the Tibetan Mahayana school:

- Sho Kwan-non.

- Ju-ichi-men.

- Sen-ju.

- Jun-tei.

- Fuku-Kenjaku.

- Ba-to.

- Nyo-i-rin.

These seven forms are in two groups of six, for the Tendai sect does not include the Jun-tei Kwan-non, and the Shin-gon omits the Fuku-Kenjaku. There is also a group of thirty-three (sometimes thirty-four) Kwan-non made up from these seven forms, which was established by the Emperor Kwazan, who abdicated the throne in the tenth century, and himself made a pilgrimage to the thirty -three shrines in the Yamato.

The Japanese Buddhists look upon these seven forms as manifestations of Avalokitesvara, but only three of them, the Sho, Sen-ju, and Ju-ichi-men (with possibly the Fuku-Kenjaku), resemble the Tibetan forms of the god of Mercy. The Ba-to is modelled after the Tibetan god, Hayagriva, while the Jun-tei resembles the Tibetan goddess, Cunda or Cuntl.

The Japanese do not absolutely follow tradition in their representations of the Bodhisattva. The crown, when without the heads, [7] is not usually five-leaved like the Tibetan, but high, complicated, and most ornate, with ornaments hanging on either side of the head to the shoulders. The breast and shoulders of the Japanese Bodhisattva are bare, but he wears a necklace and the traditional scarf, which crosses his breast from the left shoulder and is wound around the body several times, falling in graceful loops like garlands with the ends hanging over the arms.

The lower limbs are covered by a full, gracefully draped skirt-like garment which falls to the ankles, and the folds often show the influence of the Gandhara school. The lobes of the ears are always long, indicating the Indian school, but the eyes may be Japanese in shape. There is usually the urna and, behind the crown, the ushmsha. The Japanese Bodhisattva is sometimes represented dressed like a Buddha, with only his high, complicated head-dress, indicating his rank as a Bodhisattva.

I. The Sho Kwan-non (the All-wise One). In Japan the Sho Kwan-non is called 'Aryavalokitesvara', while in Tibet the term is used for the most complicated form of Avalokitesvara, which in Japan is called ' Sen-ju '.

The Sho Kwan-non is the simplest form of Avalokita, and therefore corresponds with his manifestation called 'Padmapani'. In fact, like Padmapani, he is represented as a graceful youth, standing with the right hand in vitarka (teaching) mudra, and the left denoting 'charity'. His symbol, the lotus, which is generally a bud, may be held in the right hand, or, if in the left, is sometimes in a vase. The eyes, half closed, may be Indian in form, and the lobes of the ears are always long. The hair is drawn up in a mitre-shaped ushmsha behind the complicated crown. The urna is on the forehead, and the upper lip is often outlined by a moustache, which one never sees on the Indian form. On the other hand, the antelope skin, which is sometimes worn by the Indian Padmapani, is never seen on the Sho Kwannon. His shoulders and breast are bare and he may wear many jewels, which do not, however, correspond to the thirteen traditional Bodhisattva ornaments, nor is his dress exactly the same. He may also be without jewels. The Sho Kwan-non, however, resembles more closely the Tibetan type than any of the other Japanese forms (PI. xxviii).

II. Ju-ichi-men Kwan-non (Eleven-headed). The Ju-ichi-men Kwan-non, having but two arms, resembles the Sho Kwan-non, with the exception of the head-dress, which is a crown of eleven heads disposed in two rows of three and a row between of five (the author has never seen them disposed in three tiers like the Arya-Pala). The head of Amitabha rises out of the ushnisha. The Ju-ichi-men may, however, also have four arms. In his left hand he holds a vase, in which is generally a lotus-flower, and his right hand, in 'charity' mudra, either holds a rosary or a shakujo (alarm staff). He is sometimes surrounded by a glory, in which, on each side, are five suns and a cintamani (magic jewel).

One often sees the central head of the first or second row replaced by a small figure, standing or sitting like a Buddha, closely draped, and with the hands always covered. The little figure might represent Kikuta Sanzo, an Indian prince belonging to the Ritsu sect who came to Japan from India between the seventh and eighth centuries. He was much venerated, and was always represented with the hands covered.

III. Sen-ju Kwan-non (Thousand-armed). The Sen-ju Kwan-non resembles the 'Arya-Pala' or Tantra form of Avalokitesvara. He either wears the crown of eleven heads of the Ju-ichi-men Kwan-non, or a high crown without heads. He may also have a low crown with a standing figure in the centre (PI. xli, fig. d).

His many arms are outstretched, with the exception of two pairs which are held in front and against him, the upper hands holding the patra or begging-bowl, or in 'prayer' mudra, while the lower ones hold the ambrosia vase. All the other hands hold Tantra and non-Tantra symbols. The two upper hands at the back may be raised above the crown of heads forming anjali (salutation) mudra, sometimes holding a sanko (vajra), or (but rarely) a small image of Amitabha, [8] like the Indian 'Arya-Pala'.

IV. The Jun-tei Kwan-non (San. Cuntl). The only feminine form among the seven Kwan-non is Jun-tei, who is believed to have performed the three meditations, after which she was directed in her actions by the Buddha himself.

She is called Kotl-sri, or Sapta-koti-Buddha-matri-Cunti-devi, or the goddess Cuntl, mother of 70,000 Buddhas. It is believed by the Japanese that the goddess is taken from Indian mythology and is Durga devi, wife of Siva, but the legend vaguely resembles that of the ogress Hariti. [9]

Jun-tei is sometimes represented as an angry goddess, but is usually pacific. She has the third eye and eighteen arms, all the hands holding different symbols. The two original ones are against the breast, the hands forming the mudra 'renge-no-in', [10] but it differs somewhat from the mudra of the Ba-to in that only the ring and little fingers are locked. The second fingers are upright and touching at the tips. The index fingers touch the first joints of the second fingers, thus forming a kind of 'triangular' pose. The hands of the two upper arms hold a sword and banner (PI. xii, fig. c).

According to the Butsuzo Zui the god is represented seated in the form of a woman. The ushnisha is covered by a stiff, highly decorated, cone-shaped turban, and she is clothed in flowing draperies.

V. Fuku-Kenjaku (San. Amoghapasa). Fuku-Kenjaku made his appearance in Japan much later than the others, and was not adopted by the Shin-gon sect, but is a popular deity with the Tendai sect.

He may be seated or standing with eight (or only six) arms, and wears a high crown. The original arms are held in front and against him, the hands forming namahkara (prayer) mudra. The upper arms hold Jizo's staff (shakujo) and a lotusflower. Two of the lower ones hold a rosary and lasso, and the other two form vara (charity) mudra, but the symbols may be disposed differently.

There is a form of Fuku-Kenjaku which wears the 'Ju-ichi-men' crown; but he is usually represented with a complicated crown without heads and may be without the urna. He carries the vase, in which is the lotus-flower, in the left hand, and in the right is his usual symbol, the shakujo, or alarm staff.

VI. Ba-to Kwan-non (San. Hayagrlva). Ba-to, the horse-headed Kwan-non, takes the form of the Tibetan masculine divinity Hayagrlva, and nevertheless remains for the common people the 'goddess of Mercy'.

In Tibet Hayagrlva is the protector of horses, and is supposed to frighten away the demons by neighing like a horse. There may also be some such idea in Japan, for he is worshipped chiefly in the north, where many horses are raised, and effigies of the god may be seen along the roadside. He is, in fact, the patron god of the horsedealers.

The horse's head in the hair of the Ba-to Kwan-non is a Northern Buddhist symbol, and in the legends of the Mahayana, the horse, especially if white, played an important role. In the Mahayana siltra, Sakyamuni tells of the miraculous horse [11] that saved Simhala (in reality himself, Buddha) [12] from the wiles of the Rakshasa. [13] It was on the white horse, Kanthaka, that the Buddha left his palace to become an ascetic. Legend says that the horse died of grief at being separated from his master and was reborn in the Trayastrimsa heaven as the deva Kathagata. [14]

The white horse played an important part in Chinese Buddhism in the following manner:

'In the year A. D. 63, the Chinese emperor, Mingti, had a vision. A man holding a bow and arrow [15] in his hands announced to him the appearance in the world of a "Perfect Man". He was impressed by the vision and sent a commission of eighteen men to go to the west and find him.

As the commissioners were on their way they met two men holding a white horse laden with books, images, and relics. The commissioners recognized the men as those they were seeking, and, turning back with them, brought them to Loyang, the residence of the Han emperor, where they were installed in the "White Horse Monastery", which is the earliest Buddhist sanctuary in China.' [16]

The tradition of the white horse also reached Japan, for the horse's head in Ba-to's hair must be white to be efficacious.

It is curious that a white horse (albino, if possible) is always attached to important Shinto shrines, and that the Restoration in abolishing all Buddhist symbols from the Shinto temples should have allowed the horse to remain.

Ba-to Kwan-non is represented seated, either with the legs locked, or the right knee raised in the attitude called 'royal ease'. Unlike the other types of Kwan-non, his expression is always angry and in his forehead is a third eye. The hair stands upright, and protruding from it is a horse's head, the characteristic mark of this god (PI. xxxn, fig. c).

Sometimes there are three heads, one on either side of the central head, each face having a different but angry expression, and above the central head is that of a horse (PI. xxxn, fig. d). This form closely resembles one of the manifestations of Hayagriva.

There are generally eight outstretched arms, of which five hands hold the same symbols as Hayagriva: wheel, sword, lasso, &c, and the sixth can be making the vara mudra, or holding a symbol. The two normal arms are against the breast, the hands forming the Japanese mudra called 'renge-no-in', [17] which is emblematical of the lotus-flower all fingers locked except the indexes that point upwards and touch at the tips.

VII. Nyo-i-rin Kwan-non (San. Cintamani-cakra). The Nyo-i-rin Kwan-non, called 'The Omnipotent One', is a manifestation of Avalokitesvara, seldom found outside of Japan. In Tibet, however, there are a few rare examples of this non-Tantra form, and, with a slight variation, it is also found in China.

The non-Tantra form of Avalokitesvara, in his manifestation of Nyo-i-rin, is seated European fashion, with the right foot supported by the left knee. The right elbow rests on the right knee, while the head leans on the index, or both the index and second finger of the right hand. The left hand rests on the right ankle with the palm underneath, and the left foot is supported by a small lotus asana.

This attitude of the god signifies ' meditating on the best way to save mankind '.

In China the divinity, which is found mostly in the Honan, differs from the usual Nyo-i-rin in that the head does not usually rest on the right hand, which, in that case, holds a lotus-bud. Both shoulders are covered, but the breast is bare, and he is generally accompanied by two acolytes, who are without symbols, or definite mudra unless in prayer attitude. The group may be under a 'bodhi-tree'.

In Japan, the Nyo-i-rin Kwan-non is either represented with a crown, or with the hair drawn up mitre-shaped, or in different complicated forms, which may be ornamented on the top by a moon-crescent, in the centre of which is the flame symbol. The upper part of the body is bare, with the exception of ornaments on the breast and arms. The lower limbs are covered by a skirt-shaped drapery which falls from the waist to the feet, and shows the influence of the Gandhara school in its graceful folds. The Horyuji temple owns a bronze in the traditional pose, as well as a Nyo-i-rin Kwan-non where the head is not supported by the right hand, which is in vitarka mudra. In Japan the non-Tantra form never holds a symbol.

In his Tantra form the Nyo-i-rin Kwan-non is seated in the attitude called 'royal ease' with the right knee raised, while the left is bent in the usual position of a Buddha. In this form he has six arms. His head rests on his normal right hand, and the elbow may rest on the right knee, but does not always do so. The normal left arm is extended in 'charity' mudra. Of the two arms underneath, the right holds the cintdmani against his breast, while the left, in 'teaching' mudra, holds a lotus-bud. The third right arm is pendent, holding a rosary, and the third left arm is raised, balancing a wheel on the index finger.

This form is called by the Japanese Cintdmani-cakra, probably on account of the two symbols, the magic jewel (cintdmani) and the wheel (cakra) which he carries. The Tantra form of the Nyo-i-rin does not exist outside of Japan; but although Tantra, his expression is never ferocious, nor has he the third eye. The urnd is often missing, and although the lobes of the ears are always long, the features are more Japanese than Indian, and express great calm and intense introspection.

Koyasu Kwan-non

(Holding a child).

(S.) Harili.

(C.) Sung-tse Kwan-yin.

Ogress form: Kishi-mo-jin (holding a pomegranate).

The form of Kwan-non with flowing garments and a head-drapery, holding the child, was unquestionably brought to Japan from India via Central Asia and China; but at what epoch it is most difficult to determine.

If the form was introduced into China by Fa-hian, Hiuen-tsang, or Yi-tsing, it might easily have made its appearance in Japan by the middle of the eighth century. In fact, it seems possible that the form was already known there by that time, for, according to certain accounts, the Empress Komyo, in the year A. D. 718, had a vision of Kwan-non holding a child.

The empress, so the legend runs, was with child, and prayers were being said in the holy shrine of Ise for an easy deliverance. The empress slept, and in a dream she saw Kwan-non at her bedside. She awoke, and the image, holding a child, remained and was later enshrined in a three-storied pagoda called Koyasu-to (childease), and worshipped as 'Giver and Protector of Children'.

According to tradition handed down by Japanese artists, the Empress Komyo caused a statue of the Koyasu Kwan-non, holding a child, to be modelled after her own image; and a statue of Kishi-jo-ten (owned by the Joruriji temple, Yamashiro) is also claimed to have been modelled after the Empress Komyo, who was celebrated for her beauty, both mental and physical.

The Japanese Buddhist priests place little credence in these accounts; but even if legendary, the fact remains that tradition has been handed down associating the form of Kwan-non holding the child with the eighth century, and in all probability with reason.

It is also claimed by the Japanese Buddhist priests that the forms of Kwan-non which seem feminine in aspect are, in reality, masculine, but are given a female appearance to symbolize the qualities of love, compassion, and benevolence, which are conceded to be rather feminine than masculine. The student of the iconography of these gods, however, must look upon the images of the deities which are unquestionably female in appearance as feminine, although, according to the tenets of Japanese Buddhism, the female form is only symbolical.

The Koyasu Kwan-non, 'Giver and Protector of Children', resembles too closely the Chinese 'Giver of Sons' as well as the Indian 'Giver of Children' for any doubt to exist as to its origin; and not only was the pacific form of the Indian goddess HaritI adopted by the Japanese (PI. xxxn, fig. b), but also her demoniacal form [18] as ogress, with the Indian symbol, the pomegranate. These two forms are also found in Japan, merged in one, that is, the Kwan-non holding the child and the pomegranate, [19] but the pomegranate may be missing (PI. xxxil, fig. a).

The kichi-jo-Jcwa, or pomegranate, is the special symbol of Kishi-mo-jin, the demoniacal form of Koyasu Kwan-non. When she is represented holding the child and the pomegranate, or her special symbol alone, she may be either in pacific or demoniacal form. If the former, she wears a flowing garment, a crown, and many jewels. If the latter, her hair is dishevelled and she is portrayed as a terrifying demon.

The Koyasu Kwan-non never holds the pomegranate. The mild form of Kishimo-jin holding the kichi-jo-hva and the child is represented in the Exterior Diamond section (Vajranubhava-vritti) in the Mandala of the Garbhadhatu of the Shin-gon sect, while in the temple paintings of the Ritsu sect, she is placed in the Eating Hells. She is especially worshipped in her ogress form by the Nichiren sect, who look upon her as Protector of the Saddharma-pundarika.

Among the Japanese Imperial treasures there is a small bronze statue which, according to the inscription on its base, was cast in the beginning of the seventh century A. D. The bronze is catalogued as a 'Sho Kwan-non' because of the round object in its hands which, according to the mantra of Avalokita, 'Om, mani padme, hum!' might be a magic jewel!

The compiler of the catalogue of the Imperial treasures admits that there is no traditional example of a Sho Kwan-non holding a magic jewel, when he bases his hypothesis as to the name of this idol on the fact that the Horyuji temple owns a somewhat similar statue with the cintamani on the lotus-throne instead of in the hands. He also admits that there are 'peculiarities' which may be of 'Korean art or due to Indian influence'.

As the bronze in question, [20] although more archaic, resembles in every important detail the gilt bronze statue illustrated on PI. xxx, it will easily be seen that the 'peculiarities' are indeed striking if one compares it with the traditional representation of a Sho Kwan-non.

The symbol of the Sho Kwan-non is a lotus-bud (or flower), sometimes held in a vase. The hands are in 'charity' and 'teaching' mudra; the breast and shoulders, aside from the ornaments and scarf, are bare, and the lower limbs are covered by a full, skirt-shaped garment which falls from the waist to the ankles.

The bronze figure, on the contrary, is completely covered by a long, complicated garment, which falls below tJie feet almost to the second row of petals of the lotus-throne. (In the archaic statue the garment is longer than in the larger one illustrated in the same plate.)

It is therefore evident that if the statue were standing on a flat surface the garment would fall on the ground like the long trailing robes which the Japanese court ladies have worn, in the interior, from time immemorial. The fact of the long garment alone indicates a feminine rather than a masculine divinity.

The statue in the Imperial treasures wears a crown, in which, however, there is no small image of Amitabha which would indicate the Sho Kwan-non.

The round object which is held in the left hand might be a magic jewel were it not covered by the right hand. The cintamani, both in the Tibetan form as well as in pearl shape, is represented flaming. [21] Even if it is not so portrayed, it is understood, and it would be against all tradition to represent the magic jewel held in this way. If it is not a cintamani, is it a pomegranate? There is no other Northern Buddhist symbol that is round. If, then, the divinity is feminine and holds a pomegranate, it is Hariti, which fact would prove that the worship of the goddess Haritl was introduced into Japan as early as the seventh century.

It is believed by some that the form of the goddess holding the child did not appear in Japan until the Tokugawa Shogunate (beginning of the seventeenth century), when the Roman Catholics were repressed and persecuted. It is claimed that the Catholics caused this form to be made in porcelain, or bronze, in which was inserted a cross, and that they worshipped the Koyasu Kwan-non as the Virgin Mary. There are examples of these images in the Imperial Museum at Tokyo; but this does not prove that the form of Koyasu Kwan-non did not exist long before that epoch.

One of the most popular forms of the female Kwan-non is the Byakuye, or the white-robed Kwan-non, which was first brought to Japan from China in the Ming dynasty in the fifteenth century, when Chinese painters, sculptors, and casters came to Japan, and enriched the country by more than one masterpiece.

According to the Butsuzo Zui (the Japanese manual of the Buddhist divinities) the Byakuye Kwan-non belongs to the group of thirty-three female Kwan-non, which are all represented with the flowing garments and either a crown or the head drapery of the Indian goddess. Several of the thirty-three Kwan-non indicate, either by their names or by their representations, events in the legends of Miao-chen (v. legend), while others refer to the Chinese goddess Kwan-yin.

| The Byakuye Kwan-non (sixth) (white-robed). |

When, at the command of the Buddha, Miaochen retired to the island of P'u-to to meditate, she clothed herself in white. 'White-robed' is also one of the titles of the Chinese Kwan-yin. |

|

| The Yen-Kwo Kwan-non (fourth) (sitting in bright rays). | When the father of Miao-Chen ordered her to be decapitated, 'a light breaking forth, surrounded Miao-Chen'. | |

|

The Gyo-ran Kwan-non (tenth) (fishbasket), PI. XXXI. The Ryuzu Kwan-non (second) (Dragon-head). The Anoku Kwan-non (twentieth) (protects against aquatic demons). |

When Miao-Chen saw that the son of the Dragon King of the Sea (who had taken the form of a fish) had been caught by a fisherman and was to be sold, she sent her acolyte, Chen-Tsai, to buy the fish and set it at liberty. | |

| The seventh, twelfth and thirteenth Kwan-non are represented on a lotus-flower, a lotus-petal, and a lotus-leaf on the sea. | Miao-Chen was miraculously carried across the sea to the island of P'u-to on a lotus-flower. | |

| The Ruri Kwan-non (twenty-third) holds a round object. | The Dragon King of the Sea sent Miao-Chen a luminous pearl. The Buddha gave her a peach to secure her immortality. | |

|

The Yoryu Kwan-non (first) (willow). The eleventh Kwan-non holds a willow branch and the fourteenth has a vase at her side in which is a willow branch. |

The willow is the special symbol of the Chinese goddess Kwan-yin, with which she is believed to sprinkle about her the Nectar of Life. | |

| The Haye Kwan-non (twenty-second) (clothed in leaves). | The images of Kwan-yin sent to the temples and monasteries of P'u-to by the Emperor K'ang-hsi were clothed in leaves. |

In fact, all the forms of the thirty-three female Kwan-non show Chinese influencej and were possibly introduced into Japan at the same time as the Byakuye Kwan-non by the Chinese artists, in the fifteenth century. Some of these forms, however, are not authorized by the Japanese Buddhist scriptures.

The Japanese Buddhist priests do not look upon the Butsuzo Zui as an absolute authority on Japanese Buddhism; but until another manual is compiled, the Western student must continue to refer to this Japanese manual of Buddhist divinities, especially as, in so many respects, it has been found to be perfectly reliable.

No satisfactory conclusion, however, has yet been arrived at in regard to the Koyasu Kwan-non, nor the Chinese Kwan-yin, Sung-tse. The dominant questions still remain unanswered: When did these forms first make their appearance in their respective countries? Is the Chinese princess and saint, Miao-Chen, their legendary ancestress 1

Until these two questions have been satisfactorily answered, every hypothesis is of value in that it may contain the germ of enlightenment in regard to one of the most interesting Buddhist manifestations, the goddess Kwan-shi-yin.

Visvapani (Dhyani-Bodhisattva)

Visva (vajra) pani.

(Double-thunderbolt holder).

Symbol: viha-vajra (double thunderbolt).

Fifth Dbyani-Buddha: Amoghasiddha.

Dhyani-Bodhisattva: Visvapani.

Manushi-Buddha: Maitreya.

The Dhyani-Bodhisattva Visvapani is very obscure. One seldom finds representations of the god either in bronzes or paintings. He is seated, dressed in all the Bodhisattva ornaments, his left hand lying on his lap, palm turned upward; and the right hand, in charity mudra, holds his symbol, the double thunderbolt. [22]

Visvapani is believed to be in contemplation before the Adi-Buddha, while waiting for the fifth cycle, when he will create the fifth world, to which Maitreya will come as Manushi-Buddha.

Akasagarbha (Dhyani-Bodhisattva)

(Essence of the Void Space above). [23]

(T.) nam-mk'ahi snin-po (the matrix of the sky).

(M.) oqtarghui-in jirugen (the essence of the heaven).

(C.) hu-k'ung-tsang (![]() ).

).

(J.) Kukuzo.

Mudra: vitarka (argument). vara (charity).

Symbol: surya (sun).

Akaiagarbha, whose essence is ether, is one of the group of eight Bodhisattva. He is usually standing, with his hands in vitarka and vara mudra, in which case his special symbol, the sun, is supported by a lotus at his right shoulder, while at his left is a lotus-flower supporting a book, the symbol carried by four Bodhisattva of this group.

According to Pander's Pantheon, he is seated, his legs loosely locked. His right hand holds the stem of a flower which is not a lotus, nor is there a disc rising from it as indicated by the text. [24] The left hand forms dbhaya (protection) mudra. But in the work of Oldenburg, [25] Akasagarbha is represented with a white lotus supporting the sun in his right hand; the left hand forms 'charity' mudra.

In the reproduction in the Five hundred Gods of sNar-t'an he is represented seated, holding in his left hand the stem of a lotus, from which springs a sword. [26] Both hands seem to be in vitarka mudra. In this form he resembles Manju&ri.

In both China and Japan he is represented practically in the same way. He is standing, a graceful drapery falls from his waist, and a long narrow scarf is wound loosely around the body from the left shoulder to the right hip. The breast and the right shoulder are bare, and the hair is drawn up. in a s£«#>a-shaped uslinisha like Maitreya. If there is a crown, a stupa-sh&ped ornament is in the central leaf of the five-leaved crown. There are no symbols, but the left hand forms the ' triangular pose ' (all fingers extended with the tips of the thumb and index touching, forming a triangle — see vitarka), and the right is in vara (charity) mudra. The features are Indian, with long-lobed ears, and he has the urna.

Kshitigarbha (Dhyani-Bodhisattva)

(Matrix of the Earth).

(T.) sahi-min-po (the matrix of the earth).

(M.) ghajar-un jirugen (the essence of the earth).

(C.) Ti-tsang p'u-sa (![]() ).

).

(J.) Jizo. khakkhara (alarm staff).

Mudra: vitarka (argument). vara (charity).

Symbols: cintamani (magic jewel).

Kshitigarbha belongs to the group of eight Bodhisattva, and is, according to Beal, the great ' Earth Bodhisattva ', invoked by Buddha to bear witness that he resisted the temptation of Mara, god of Evil. [27]

The name of Kshitigarbha often appears in the ceremonies of initiation to the Northern Buddhist priesthood, and he is believed to be the Bodhisattva of the Mysteries of the Earth.

Kshitigarbha, unlike Ti-tsang in China, or Jizo in Japan, seems in no way connected with the infernal regions, although he is considered in both countries to be their Indian manifestation. In Tibet the 'Over-Lord of Hell' is Yama, while in China Yama holds a subordinate position under Ti-tsang, who is 'Over-Lord of Hell'. In Japan Jizo, while looked upon as incarnation of Ti-tsang (and Kshitigarbha), holds a subordinate position, and Emma-O is 'Over-Lord of Hell'.

But although Kshitigarbha, Ti-tsang, and Jizo hold different posts in their respective countries, the three manifestations have this in common, that they are believed to have made a vow to do the work of saving all creatures from hell during the interim of the death of Sakya-muni and the advent of Maitreya.

In Tibet statues of Kshitigarbha are rare and are seldom found outside of the group of 'eight Bodhisattva', where he is represented, like all the other DhyaniBodhisattva, with the thirteen ornaments, and is standing with his right hand in 'argument', while his left hand his in 'charity' mudra. His symbol, the magic jewel, generally in shape of a flaming pearl, [28] is supported by a lotus-flower on a level with his right shoulder. There is sometimes a book supported by a lotus-flower at his left shoulder.

Kshitigarbha may also be represented seated, holding an alarm staff in his two hands. On his head is a five-leaved crown, in each leaf of which is the representation of a Dhyani-Buddha (PI. xxxin, fig. c). The chodpan crown is only worn by the Northern Buddhist priests and never by the gods; but this bronze is undoubtedly the representation of a god, for the personage is seated on the lotus-flower, and the alarm staff has six loose rings, which number indicates a Bodhisattva. As Kshitigarbha is especially worshipped by those entering the Northern Buddhist priesthood, it may be that he is adored by them in this special form.

Among the temple banners discovered by Sir Aurel Stein in Chinese Turkestan, and now in the British Museum, are some very beautiful paintings of Kshitigarbha. He is either represented seated, holding the alarm staff in his right hand and the naming pearl in his left, or standing, with one foot on a yellow and the other on a white lotus, holding the flaming pearl in his right hand. In almost all the temple banners from the Khotan his head is enveloped in a turban-shaped head-dress with the ends falling over the shoulders.

Kshitigarbha is also represented as Master of the Six Worlds of Desire, which is a very popular form of representing the god in Japan in temple pictures. He is surrounded by:

- A Bodhisattva, symbolizing the heaven of the gods.

- A man, symbolizing the world of men.

- A horse and an ox, symbolizing the world of animals.

- A demon armed with a pitchfork, symbolizing the hells.

- An asura, representing the world of asuras.

- A preta, representing the world of spectres.

A temple picture representing this subject was found by Sir Aurel Stein in Chinese Turkestan, proving that the form of Kshitigarbha with his alarm staff and as 'Master of the Six Worlds of Desire' was brought into Japan from Central Asia.

In Japan he may wear a crown, and be represented carrying a lotus-flower in his left hand. The right either holds the magic jewel, or is in mystic mudra: the fingers are all extended upwards, and the thumb bent inwards touching the palm, a mudra which the Japanese call 'semui'. It seems to be a corruption of the vitarka mudra. His usual form, however, in Japan, is his manifestation, Jizo.

(Over-Lord of Hell).

Chinese manifestation of Kshitigarbha.

Symbols: khakkliara (alarm staff).[29] cintamani (magic jewel).

Before the god Ti-tsang became a Dhyani-Bodhisattva and 'Deliverer from Hell', [30] he was, according to the Ti-tsang siltra, a Brahman maiden, and his legend runs as follows: There was once a Brahman maiden whose mother died slandering the 'Three Treasures' (Buddha, Dharma, Sangha), and to save her parent from the torments of the damned, she made daily offerings before the image of an ancient Buddha, imploring his help. One day she heard a voice telling her to return home and meditate on the name of Buddha. She did so, and while in deep meditation her soul visited the outposts of Hell, where she met the Demon-Dragon, who informed her that through her prayers and pious offerings her mother had already been released from Hell. Her heart was so touched by all the suffering souls she saw still in Hell, that she vowed through innumerable kalpas to perform acts of merit to release them.

In this same stltra Buddha announces to Manjusri that the Brahman maiden has become a Bodhisattva through her acts of merit and that her name, as such, is 'Ti-tsang'. Thus the Brahman maiden became a masculine divinity and 'Over Lord of Hell'.

Although Ti-tsang is the Begent of Hell, he does not judge the souls but, according to Edkins, ' opens a path for self-reformation and pardon of sins '. He seeks to save mankind from the punishments inflicted on them by the ten Judges or Kings of Hell.

Ti-tsang is sometimes represented surrounded by the ten Kings of Hell, of which the fifth, Yen-lo-wang, is the Chinese manifestation of the Indian god of Death, Yama. The ten kings are always represented standing when in his presence.

Ti-tsang may be represented standing or sitting, and always as a round-faced, benevolent person, carrying his special symbol, the alarm staff, topped by loose rings, in his right hand, and the magic jewel in his left.

Women who have ugly faces pray to him and believe that, if they are devout enough, they will be born for a million Jcalpas with beautiful countenances.

His place of pilgrimage is at Chin-hua-shan, on a mountain crater, where a pagoda, ornamented with images of Ti-tsang and dedicated to him, soars above the monasteries and temples that cluster about it, and forms a pious landmark from the plains below.

Japanese Manifestation of Kshitigarbha.

Symbol: sliakujo[31] (staff topped with loose metal rings).

Jizo is the 'Compassionate Buddhist Helper' of those who are in trouble and of women desiring maternity, in which latter case he is called Koyasu Jizo. He is also the patron god of travellers, and, as such, his image is often seen used as a signpost on the highways. Stones are sometimes heaped about his statues by bereaved parents, who believe that Jizo will

'relieve the labours of the young, set by the hag Sho-zuko-no-baba, to perform the endless task of piling up stones on the banks of the Sai-no-Kawara, the Buddhist styx' (Satow).

The position of Jizo in Hell does not seem to be so closely defined in Japanese Buddhism as his manifestation in China. During the Kamakura period Jizo was believed to be an incarnation of Yama-raja, king of Hell, the idea probably coming from China; but he has never been confounded, however, with Emma-O, 'Over-Lord of Hell'.

Jizo is worshipped as Master of the Six Worlds of Desire. In this form he is only represented in paintings, and is surrounded by a Boddhisattva, a man, a horse and an ox, a demon, an asura, and preta, thus symbolizing the Six Worlds of Desire.

The Tendai sect worship a group of six Jizos, or 'Compassionate Helpers', which may correspond to the 'Six Muni', presidents of the six worlds of rebirth of Northern Buddhism. Three of these Jizos have the title of ' King of Hell '.

Legend recounts that a certain holy monk went to visit Emma-O, King of Hell, and saw Jizo sitting among the damned, in the lowest of the hells, undergoing torments for the sins of mankind (Satow). This, however, would not be incompatible with his being king of Hell, for Yama, the Tibetan king of Hell, undergoes the same torments as his subjects.

Jizo is usually represented as a shaven priest with a benevolent countenance, sitting or standing. [32] He wears the monastic robe, and, although a Bodhisattva, has no ornaments, but may wear a crown. In his right hand he carries his distinctive symbol, the sliakujo, an alarm staff topped by six metal rings, which represent his vow to save all who follow the Six-Fold Path. In his right hand he may carry the magic jewel, a rosary, or a Kongo flag. He is sometimes represented without the shakujo, but rarely.

Sarvanivarana-Vishkambhin (Dhyani-Bodhisattva)

(The Effacer of all Stains).[33]

(T.) sgrib-pa rnam-sd (he who makes the realms of darkness).

(M.) tuitger-tejin arilghaqci (the cleaner of moral spots).

(C.) Ch'u-chu-chang (![]() ).

).

(J.) Jo-gai-sho (removing-covering-obstacle).

Mudra: vitarka (argument). vara (charity).

Symbol: candra (moon).

Colour: white.

In the Lotus of the Good Law the Bodhisattva Sarvanivarana-vishkambhin is mentioned as holding conversation with Gautama Buddha, during which he expresses the desire to see the wonderful form of Avalokitesvara. Thereupon Sakya-muni sends him to Benares, where Avalokita miraculously appears to the sage Vishkambhin, who ever after 'enumerates the qualities of this divine being'. [34]

Vishkambhin belongs to the group of eight Bodhisattva found in the Northern Buddhist temples, and according to Oldenburg [35] is standing with hands in vitarka and vara mudra. His special symbol, the full moon, and a symbol which is also carried by several of the Bodhisattva of the group, the pustaka (book), are supported by lotusflowers at either shoulder.

According to Pander, [36] he may hold the sun, but the disc is more probably meant to represent the full moon, [37] for the sun is the special symbol of Akasagarbha of this group. The Bodhisattva is seated with legs closely locked. The right hand, in vitarka mudra, holds the stem of a lotus on which is a disc, and the left is in vara mudra.

If in company with the Buddha, as Liberator of the Serpents, and Maitreya, Avalokita, and Manjusri, he may hold a cintamani and an ambrosia cup.

In his Yi-dam form he stands with legs apart, on a prostrate personage lying face downward. He wears a tiger-skin hung around his waist, and a garland of heads. On the top of his ushnisha is a half-thunderbolt; he has the third eye; his right hand holds a kapCda (skull-cup) and his left a grigug (chopper)

| PLATE XXIX | ||

|

|

|

| a. Ratnapani | b. Kwan-yin (Sung-tse) | |

|

|

|

| c. Kwan-yin (Sung-tse) | d. Kwan-yin | |

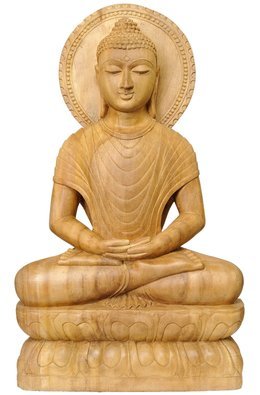

| PLATE XXX |

|

| Kwan-non |

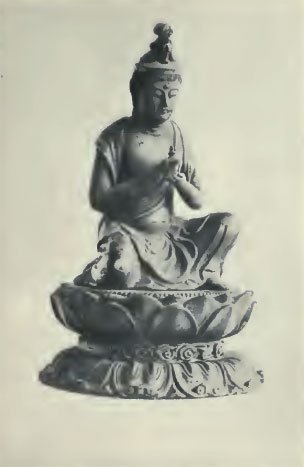

| PLATE XXXI |

|

| Kwan-non (Gyo-ran or 'fish basket') |

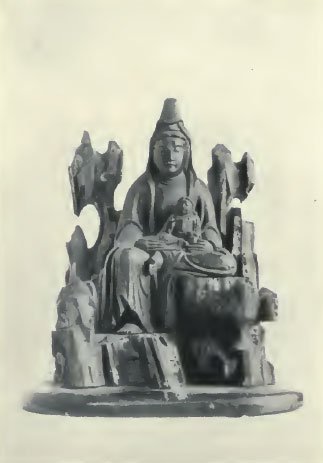

| PLATE XXXII | ||

|

|

|

| a. Ki-shi-mo-jin | b. Koyasu Kwan-non | |

|

|

|

| c. Ba-to Kwan-non | d. Ba-to Kwan-non | |

| PLATE XXXIII | ||

|

|

|

| a. Jizo (Kshitigarbha) | b. Jizo | |

|

|

|

| c. Kshitigarbha/td> | d. Jizo | |

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

According to some, 100 years after the introduction of Buddhism into Japan, a.d. 552. Others claim 150 years later.

[2]:

v. Glossary.

[3]:

Founder of the Hosso sect in China (Yogacarya school).

[4]:

v. Beal, Buddhist Records of tlis Western World, translated from the Chinese of Hiuan-tsang, vol. ii, pp. 60 and 127.

[5]:

The Shin-gon sect belongs to the Yogacarya or Tantra school.

[6]:

In the Shinto religion the gods are not 'imaged'.

[7]:

The crown of heads is only found in Chinese Turkestan, China, and Japan.

[8]:

v. Butsuzo Zui, Japanese manual of the Buddhist Pantheon.

[9]:

Hariti is believed, in Japan, to have had 100,000 children.

[10]:

v. Glossary.

[11]:

The horse was white, according to the Abhinishkramana sutra.

[12]:

Burnouf, Introduction.

[13]:

Cannibal demons.

[14]:

Fa-hian.

[15]:

Hayagriva sometimes carries a bow and arrow.

[16]:

Lloyd, Development of Japanese Buddhism.

[17]:

It resembles the mudra of k'Lu-dban-rgyd-po or 'Buddha Liberator of the Nagas'. v. Glossary.

[18]:

In China the demoniacal form was never adopted, nor, judging from the excavations in Chinese Turkestan, was it ever popular in Central Asia.

[19]:

In Japan, however, the ogress form, Kishi-mojin, is not looked upon as a demoniacal form of Koyasu Kwan-non, and nei her form is authorized in the Japanese Buddhist scriptures.

[20]:

v. small image, PI. xxx.

[21]:

On a Japanese temple banner, belonging to M. Goloubew, smoke arises from the flaming pearl held in the right hand of Jizo.

[22]:

v. Pander, Das Pantheon des Tschangtscha Hutuktu, iii. 81.

[23]:

E. Denison Ross, Sanskrit-Tibetan-English Vocabulary, Memoirs of the Asiatic Society of Bengal.

[24]:

p. 76, illust. 150.

[25]:

No. 1, Selection of Images of the three hundred Buddhist divinities, &c.

[26]:

Grunwedel, Mythologie du Bouddhisme, p. 143.

[27]:

According to the usual Buddhist legend, Buddha invoked the earth goddess Prithivi or Sthavara.

[28]:

v. group of eight Bodhisattva in the Museum fur Volkerkunde, Berlin, and illustration, Oldenburg, Izviestia, Sfc. (Bull. Musee Pierre-le-Grand), St. Petersburg, 1909.

[29]:

Carried by mendicant Buddhist monks to 'warn off small animals lest they be trod upon and killed' (Waddell). v. Khakkliara.

[30]:

Ti-tsang-wang p'u-sa.

[31]:

San. KJiakkhara; v. Glossary.

[32]:

v. PI. xxxiii, figs, a, b, and d.

[33]:

E.Denison Ross, Sanskrit-Tibetan-English Vocabulary, Memoirs of the Asiatic Society of Bengal.

[34]:

Burnouf, Introduction, p. 201.

[35]:

Oldenburg, III. (Materially: 5, note on several images and Bodhisattva.)

[36]:

Das Pantheon des Tscliangtscha Hutuktu, p. 76, illus. 149.

[37]:

Sarva-nivarana never carries the moon-crescent, but the full moon, and as his Sanskrit name signifies 'effacer of spots', and his Japanese name 'removing-covering-obstacle', may there not be here a reference to the eclipse?