The gods of northern Buddhism

their history, iconography and progressive evolution through the northern Buddhist countries

by Alice Getty | 1914 | 98,662 words

Indispensable reference for art historians, scholars of Eastern philosophy and religion. Wealth of detailed scholarly information on names, attributes, symbolism, pictorial representations of virtually every major and minor divinity in Mahayana pantheon, as worshipped in Nepal, Tibet, China, Korea, Mongolia, and Japan. 185 black-and-white illustrat...

Chapter I - Adi-buddha

| Table I | ||

| Adi-Buddha |

|

I. Vajradhara. |

| II. Vajrasattva (J.) Kongosatta. | ||

(T.) mc'og-gi dan-pohi sans-rgyas (lit. most excellent first Buddha); or dus-kyi hkor-hhi mts'an (lit. the saint of (the religion of the) wheel of Time).

(M.) anghan burhan (the beginning deity).

In the Guna Karanda Vyuha it is written:

'When nothing else was, Sambhu was: that is the Self-Existent (svayambhu): and as he was before all, he is also called Adi-Buddha.' [1]

The first system of Adi-Buddha was set up in Nepal [2] by a theistic school called Aisvarika, but was never generally adopted in Nepal or Tibet, and had practically no followers in China and Japan. [3]

The Nepalese school supposed an Adi-Buddha infinite, omniscient, self-existing, without beginning and without end, the source and originator of all things, who by virtue of five sorts of wisdom (jnana) and by the exercise of five meditations (dhyana) evolved five Dhyani-Buddhas or Celestial Jinas called Anupapadaka, or 'without parents'.

When all was perfect void (maha-Sunyata) [4] the mystic syllable aum [5] became manifest, from which at his own will the Adi-Buddha was produced. At the creation of the world he revealed himself in the form of a flame which issued from a lotusflower, and in Nepal the Adi-Buddha is always represented by this symbol. [6]

All things, according to Hodgson, were thought to be types of the Adi-Buddha, and yet he had no type. In other words, he was believed to be in the form of all things and yet to be formless, to be the

'one eternally existing essence from which all things are mere emanations' (Monier Williams).

According to the system, Adi-Buddha was supposed to dwell in the Agnishtha Bhuvana (the highest of the thirteen [7] Bhuvana, or celestial mansions), quiescent and removed from all direct communication with the world which he had caused to be created by the Dhyani-Bodhisattva, through the medium of the Dhyani-Buddha.

It was believed that neither the Adi-Buddha nor the Dhyani-Buddha ever descended to earth, but left the creation and direction of the world's affairs to the active author of creation, the Dhyani-Bodhisattva, and that as they were absorbed in perpetual contemplation, prayers were not to be addressed to them.

Other sects in Nepal, besides the Aisvarika, set up an Adi-Buddha, the most important being the Svabhavika, which afterwards became the most popular Buddhist sect in China.

Svayambhu, or Adi-Buddha, was called Isvara by the Aisvarika, and Svabhava by the Svabhavika; but he was also given such special names as Vairocana, Vajrapani, Vajradhara, and Vajrasattva. In the Namasangiti (compiled before the tenth century a.d.) Manjusri, god of Transcendent Wisdom, is referred to as Adi-Buddha.

The Adi-Buddha is always represented as a 'crowned' Buddha, that is to say, that although he is a Buddha, he wears the five-leaved crown as well as the other traditional ornaments of a Dhyani-Bodhisattva, and is dressed in princely garments. His consort is Adi-Dharma (Adi-Prajna).

In Japan, although the term 'Adi-Buddha' is not known, the Dhyani-Buddhas, Amitabha and Vairocana, are both looked upon as Supreme. They are not believed, however, to have evolved the five Dhyani-Buddhas. The Amida sects claim that Vairocana and the other three Dhyani-Buddhas are manifestations of Amitabha, while the Shin-gon sect claims that Amida and the other three Dhyani-Buddhas are manifestations of Vairocana. They are never worshipped in company with their sakti [8] while in Nepal and Tibet the Adi-Buddha is frequently represented with his female energy, in which case he is called Yogambara, [9] and the sakti, Jnanesvari.

Vajradhara (Adi-Buddha)

(Thunderbolt-bearer).

(T.) rdo-rje-hc'an (He who holds a thunderbolt).

(M.) Ocirdara (corruption of Vajradhara), or Vacir bariqci (He who holds a thunderbolt).

Symbols: vajra (thunderbolt), ghanta (bell).

Mudra: vajra-hum-kara.[10]

Colour: blue.

Sakti: Prajnaparamita.

Other names: Karmavajra, Dharmavajra.

Vajradhara is the supreme, primordial Buddha without beginning or end, lord of all mysteries, master of all secrets. It is to him the subdued and conquered evil spirits swear allegiance and vow that they will no longer prevent or hinder the propagation of the Buddhist faith. He is thought to be too ' great a god and too much lost in divine quietude to favour man's undertakings and works with his assistance, and that he acts through the god Vajrasattva, and would be to him in the relation of a Dhyani-Buddhi to his human Buddha .[11]

Vajradhara is looked upon as Adi-Buddha by the two greatest sects of the Mahayana school: the dKar-hGya-pa (Red Bonnets) and the dGe-lugs-pa (Yellow Bonnets). [12]

He is always represented seated, with his legs locked and the soles of his feet apparent, and wears the Bodhisattva crown as well as the dress and ornaments of an Indian prince. He has the urna and ushnisha. [13] His arms are crossed on his breast in the vajra-hum-kdra mudra holding the vajra and ghanta. These two symbols may, however, be supported by flowering branches on either side, the stems being held in the crossed hands, which is his special mystic gesture (v. PI. n, fig. b, and PI. in, fig. c).

As 'Karmavajra' (Dorje las) his left hand holds a lotus and his right hand is in vitarka (argument) mudra: arm bent, hand raised, palm turned outward, all fingers extended upward except the index and thumb which touch at the tips, called 'triangular pose' (v. vitarka).

As 'Dharmavajra' (Dorje c'os) his right hand balances a double vajra at his breast, and the left holds the bell on the hip.

When Vajradhara holds his sakti in yab-yum [14] attitude, his arms are crossed at her back, holding his usual symbols. The yum holds a vajra and kapala (skull-cup).

Vajrasattva [15] (Adi-Buddha)

(Whose essence is the Thunderbolt).

Buddha of Supreme Intelligence.

(T.) rdo-rje sems-dpah (soul of the thunderbolt).

(C.) Suan-tzu-lo-sa-tsui (![]() ).

).

(J.) Kongosatta (essence of a diamond).

Symbols: vajra (thunderbolt), ghanta (bell).

Colour: white.

Bodhisattva of Akshobhya (Dhyani-Buddha) and chief (Tsovo) or president of the five Dhyani-Buddhas.

The position of Vajrasattva in the Mahayana pantheon is difficult to determine. He is looked upon as the spiritual son of Akshobhya, and is at the same time Tsovo or chief of the five Dhyani-Buddhas. M. de la Vallee Poussin identifies him with Vajradhara. Eitel calls him the sixth Dhyani-Buddha of the Yogacharya school. [16]

{GL_PAGE:5}The Svabhavika sect in Nepal identified Svabhava [17] (Adi-Buddha) with Vajrasattva, who, according to the Nepalese Buddhist writings, manifested himself on Mount Sumeru in the following manner. A lotus-flower of precious jewels appeared on the summit of the mountain which is the centre of the universe, and above it arose a moon-crescent upon which, 'supremely exalted', was seated Vajrasattva.

It is not probable that the image of the AdiBuddha Vajrasattva is here meant, but rather the symbol which designates the Adi-Buddha, a lihga-shaped flame. If the moon-crescent, which arose above the lotus-flower, is represented with the flame symbol in the centre, instead of the 'image of Vajrasattva', it forms a trident. [18] The special emblem of the Svabhavika sect was a trident rising from a lotus-flower, which, if we accept the above hypothesis, symbolized the manifestation of Vajrasattva as Adi-Buddha on Mount Sumeru.

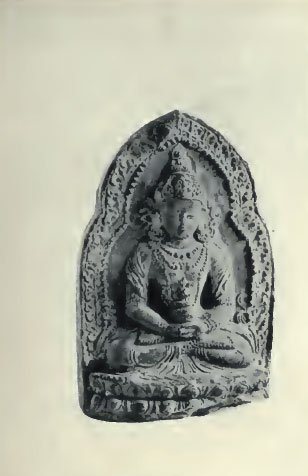

In the Musee Guimet there is an example of a Bodhisattva (or 'crowned' Buddha), with four heads[19] seated, with the legs locked, and balancing a vajra on his hands in dhydna mudra. As the Adi-Buddhas are always represented with the Bodhisattva ornaments, it may be a representation of Vajrasattva as Adi-Buddha; and since Brahma, chief of all the Brahman gods, has four heads, the idea of representing Vajrasattva in the same manner may have been borrowed from Brahmanism to distinguish Vajrasattva as Adi-Buddha, chief of all the gods of the Mahayana system, from his manifestations which occupy a less exalted position in the Northern Buddhist pantheon.

As sixth Dhyani-Buddha, Vajrasattva presides over the Yidam, [20] and has the same relation to the Adi-Buddha that the Manushi (human) Buddha has to his ethereal counterpart or Dhyani-Buddha. The sixth sense is believed to have emanated from him, as well as the last of the six elements of which man is composed — the manas, or mind (v. Tlie Dhyani-Buddhas).

Vajrasattva is always represented seated, wearing the five-leaved crown and the dress and ornaments of a Dhyani-Bodhisattva. He generally holds the vajra against his breast with the right hand, but the vajra may be held in the hand or balanced on its point in the palm of the hand. With the left, he holds the gJmnta on his hip (PL iv, fig. c).

When seated on a white lotus, he is looked upon by certain sects as Guardian of the East. [21]

Unlike the other Dhyani-Buddhas, he is always crowned with or without his sakti, whom he presses against his breast in the yab-yum [22] attitude, with the right hand holding the vajra, while the left holds the ghanta on his hip. The yum holds the Jcapala (skull-cup) and vajra.

In Nepal, according to Hodgson, he is seldom represented in statuary form, but is more often met with in paintings, and especially in miniatures. In Tibet, however, bronzes of Vajrasattva are not infrequently found, while in paintings, especially in mandala, [23] he is often met with. In Japan he is found in statues as well as in paintings, and is called 'Kongosatta'. The Japanese look upon Trailokya-vijaya Bodhisattva as a form of Vajrasattva.

Kongosatta [24]

(Japanese form of Vajrasattva).

Symbols: vajra (thunderbolt), ghanta (bell).

Colour: pinkish white.

Vahana [25]: elephant (white).

There is a divergence of opinion in Japan in regard to the divinity whose representations seem to correspond with that of Vajrasattva in Tibet. He is seated with the legs locked, dressed like the usual Japanese Bodhisattva. The right hand holds the vajra at the breast, like Vajrasattva. The left hand rests the ghanta on the left knee instead of holding it on the hip like Vajrasattva. He may have from two to six or more arms, and has both a 'mild' and 'ferocious' form.

The 'mild' form has usually two arms, and is seated on a lotus-throne which is often supported by an elephant, [26] for which reason he is sometimes mistaken for Fugen (Samantabhadra), especially as the elephant frequently has three heads [27] and is always white (PI. IV, fig. b, and PI. v, fig. c). The vajra and ghanta, however, are not Fugen's symbols (v. Fugen), and the elephant may have four heads. If this form has four or six arms, the original arms hold the same symbols as the above, and in the same manner, while two of the accessory arms always brandish the bow and arrow (v. TrailoJcya-vijaya). If there are six arms, the symbols held by the fifth and sixth may vary.

Kongosatta may also be supported by four elephants, on each of which is one of the Lokapala or guardians of the Four Cardinal Points (PI. iv, fig. a). He holds the vajra and ghanta; but instead of the bell, he may hold a lotus, which is the symbol of Samantabhadra, and this seems to be a form of Kongosatta and Fugen merged into one. One often finds him in Japanese as well as in Tibetan mandala (magic circles) in the centre, surrounded by the four Lokapala. He is always represented seated, holding the vajra against the breast with the right hand, and the ghanta in the left which lies on his lap.

The 'ferocious' form has six arms, a third eye, and a ferocious expression. Above the forehead is a skull, and a vajra issues from the tishntsha. The vajra and ghanta are carried in the same position as the above form, and he holds the bow and arrow and other Tantra symbols. His colour is red. The author has never seen the 'ferocious' form supported by an elephant. He is worshipped by the Tendai and Shingon sects, and is called 'Aizen-myo-o (PL v, fig. b, and PI. xxxix, fig. a). He is found in a triad with Kwan-non and Fudo and, in spite of his ferocious appearance, is looked upon by the common people as god of Love. As both the 'mild' and 'ferocious' forms hold the same symbols, in the same manner, may not Aizen-myo-6 be termed the 'ferocious' form of Kongosatta?

|

PLATE I |

|

|

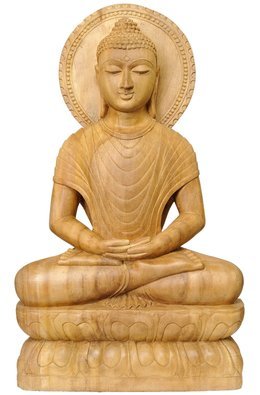

| Above: Gautama Buddha |

| PLATE II | ||

|

|

|

| a. Dai-Nichi-Nyorai | b. Vajradhara | |

|

|

|

| c. Akshobhya | d. Akshobhya | |

| PLATE III | ||

|

|

|

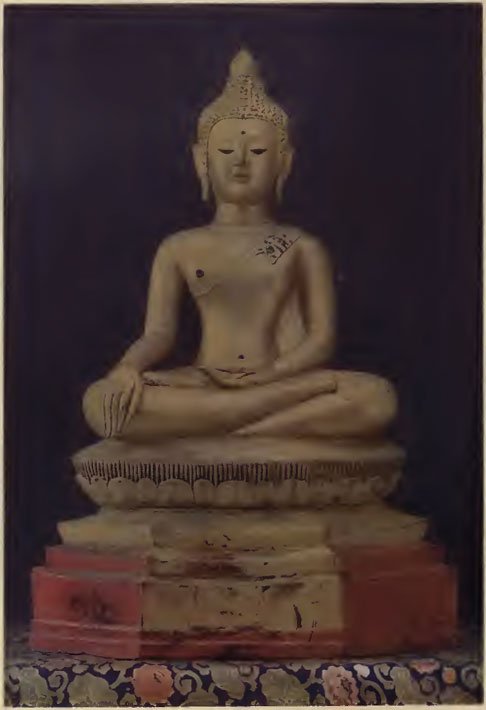

| a. Amitayus | b. Gautama Buddha | |

|

|

|

| c. Vajradhara | d. Manjusri | |

| PLATE IV | ||

|

|

|

| a. Kongosatta | b. Kongosatta | |

|

|

|

| c. Vajrasattva | d. Esoteric Buddha | |

| PLATE V | ||

|

||

| a. Samvara (?) | ||

|

||

| b. Aizen-Myo-o | ||

|

||

| c. Kwan-non on a Lion, Kongosatta on an Elephant | ||

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Adi (first), Buddha (wise one).

[2]:

According to Grunwedel, in the eleventh century a.d. Other authorities give earlier dates, but also posterior to the system of five Dhyani-Buddhas.

[3]:

Although the system of Adi-Buddha was not adopted in Japan, the Amitabha sects look upon Amida as the One Original Buddha (Ichi-butsu), while the Hosso, Tendai, Kegon, and Shin-gon sects call Vairocana (Dai-nichi Nyorai) 'the Supreme Buddha'.

[4]:

v. Glossary.

[5]:

The mystic syllable aum signifies the Tri-ratna (Three Jewels): Buddha (a), Dharma (w), Sangha (u), or Buddha, the Law, the Community. In the mantra, it is written om. v. Tri-ratna and om.

[6]:

The flame symbol is also represented in the centre of a moon crescent, v. PI. xix, fig. d.

[7]:

In Nepal, 13; in India, 10 Bhuvana.

[8]:

Female energy.

[9]:

Adi-Buddha as Yogambara, or the esoteric form (PI. iv, fig. d), is represented nude with the legs closely locked. He wears no jewels and has the urna and ushnlsha (v. Glossary). Hodgson, Sketch of Buddhism derived from the Bauddha Scriptures of Nepal, pub. Eoyal Asiatic Society, vol. ii, 1830, PI. i, fig. a.

[10]:

Mystic gesture; v. Glossary.

[11]:

Schlagintweit, Buddhism in Tibet, p. 51.

[12]:

Prof. S. Chandra Vidyabhflshana, ' On certain Tibetan scrolls and images', Memoirs of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, vol. i, No. 1.

[13]:

v. Glossary.

[14]:

The yum (sakti) in the embrace of the god (yab).

[15]:

Vajra (thunderbolt or diamond), sattva (essence).

[16]:

The Dhyani-Buddhas.

[17]:

Sva (own), bhava (nature). Hodgson, The Languages, Literature, and Religion of Nepal and Tibet, p. 73.

[18]:

v. illustration, G. d'Alviella, The Migration of Symbols, fig. 159. Also see Stupa.

[19]:

Collection Bacot, No. 28. It is catalogued as 'Brahma' (Ts'angs-pa), but Ts'angs-pa does not carry the vajra. In the Pantheon des Tschangtscha Hutuktu, there is the representation of a Bodhisattva with four heads balancing a wheel, which seems to indicate Vairocana (v. Vairocana).

[20]:

Protectors of Buddhism.

[21]:

v. Lokapala.

[22]:

v. Glossary.

[23]:

Magic circles; v. Glossary.

[24]:

Kongo (diamond), satta (saltva - element or essence)

[25]:

v. Glossary.

[26]:

The elephant is the mount of the spiritual father of Vajrasattva, the Dhyani-Buddha Aksho-bhya.

[27]:

Fugen is, however, usually supported by a white elephant with one head and six tusks, but it may also have only two tusks.